![]()

INTRODUCTION

Poems written in early youth and poems written in old age have one thing in common. Their value is usually determined in relation to something they’re not—the masterworks of middle age, composed at the height of one’s powers. But if a poet’s late work is usually seen as a kind of summation, a gathering of forces, bathed in the light of the wisdom accumulated during a lifetime, poems written early in a poet’s career are cursed by what they aren’t yet. Granted, occasionally a young writer bursts on to the scene with work so extraordinary, so finished, that he or she challenges such orthodoxies. Arthur Rimbaud, “heaven-born boy with a Hellfire tongue,” as Stephen Spender almost reverently addressed him in a late poem, is a case in point. But young Stephen Spender was no Rimbaud (or “Rimb,” as he addressed him in that poem).1 And therein lies, precisely, the appeal of the present volume.

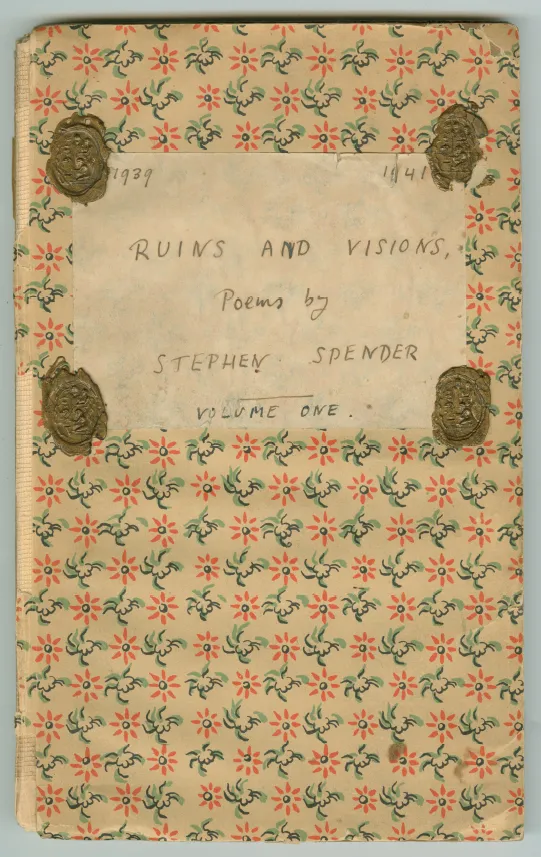

Poems Written Abroad is a slim, unpublished manuscript compiled by eighteen-year-old Stephen Spender during a three-month summer vacation in 1927 in France and Switzerland. He wrote his poems in a blank, octavo-sized notebook of thirty-six leaves with batik covers that he had purchased while in France.2 He numbered the pages, added a dedication, and drew an elaborate cover illustration. Most of the poems show little or no revision, which suggests that they were fair copies from drafts written down elsewhere. In other words, Poems Written Abroad was not a casual affair. This was not the last time, incidentally, that Spender used a special notebook for his poetry. The Lilly Library owns two notebooks with fancily ornamented covers containing Spender’s drafts for Ruins and Visions (dated 1939–1941; see fig. 0.1). The aesthetic aspects of bookmaking had appealed to him early on. In 1926, for example, he gathered several pamphlets of poetry, by authors as diverse as Laurence Binyon and Walt Whitman, into a nineteenth-century half-calf binding, which he proudly inscribed, inside the front cover: “bound by me in 1926—Stephen Spender.” Two years later, he used a hand press he had acquired to typeset a small collection of his own poems, Nine Experiments, as well as his new friend W. H. Auden’s first collection of poems.3

Figure 0.1. Stephen Spender, draft notebook for Ruins and Visions, vol. 1. 1939–1941. The Lilly Library.

How and why Spender lost track of Poems Written Abroad, a work in which he had invested so much time and care, remains a mystery. Sometime before 1956, John Negley Yarnall, a professor of English at Wilson College in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and a collector of manuscripts and rare books, purchased the autograph, along with manuscripts by W. H. Auden and Virginia Woolf, from David Randall, who then headed the rare books department at Scribner’s in New York.4 When Randall became the first director of the newly created Lilly Library at Indiana University, he was looking to build a “representative collection” of manuscripts by modern writers, and he got back in touch with Yarnall, now a Professor of English at Montgomery College in Maryland. Yarnall agreed to sell his Spender, Woolf, and Auden autographs back to Randall, for a total of $2,500.5 It appears that Yarnall had, at some point, considered editing at least the Spender poems for publication and had even written to Spender himself to get his permission.

Yarnall provided Randall with the originals of his correspondence with Spender. They tell a somewhat comical story. It seems Spender at first drew a blank when asked about Poems Written Abroad.6 But when Yarnall sought him out, after a lecture Spender had given at Georgetown University, he finally remembered and asked to see the manuscript. Yarnall obliged and dispatched it to Northwestern University, where Spender was teaching at the time. And that, for a while, was the last thing he heard. Spender had misplaced the poems without even taking a look; he probably thought they were just another one of those manuscripts that friends and strangers alike would mail him for inspection and approval: “I get sent things to read all the time.” Eventually, much to Yarnall’s relief, they turned up again and Spender found them to be not as “bad as he had feared.”7 Yarnall got the green light.

And, indeed, bad they are not. Poems Written Abroad provides us with a unique window onto an important summer in the life of one of the most important British poets of the twentieth century. In “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” an essay written when Spender was just ten years old, T. S. Eliot claimed that the mind of a poet was like the shred of platinum that acts as a catalyst in a chemical reaction, bringing together the old and the new and thus vanishing in the process.8 That is not how things worked for Stephen Spender or, I would suggest, for any poet of significance. Spender’s presence—that of the adolescent Stephen as well as that of the person and poet he was to become—is felt on every page of this manuscript, as are the forces of tradition he grapples with, from Milton and Shakespeare to Rimbaud and T. S. Eliot. And so, too, are the beginnings of the unique Spenderian voice, a mix of pose, erudition, and, at times, a kind of honesty so disarming that it turns into another pose.

Born on February 28, 1909, in Kensington into a literary and artistic family, Stephen Harold Spender (fig. 0.2) had, from the beginning of his life, opportunities others would dream about. His father, Harold Spender, was a journalist and Liberal politician. His formidable uncle, J. A. Spender, edited the Westminster Gazette, while his grandmother, Lillian Spender, had been a prolific novelist, author of such books as Jocelyn’s Mistake and Mark Eylmer’s Revenge. Not to be outdone, Harold tried his hand at novel writing too, with mixed success: “He searched neither for startling originality of plot nor hair-raising adventures,” observed one reviewer about Harold’s One Man Returns (1913), while the Spectator pointed out that the parents Mr. Spender had introduced as characters in the first chapters of Call of the Siren (1914) were disappointingly forgotten later in the book “by the author and their own children.”9 Meanwhile, Violet, Harold’s wife and Stephen’s mother, painted and wrote poetry ranging from lugubrious reflections on the war that had taken her brother’s life to a mock obituary for her cook, the full irony of which probably wasn’t clear to her: “She cooked the food for persons nine, / As well as friends who came to dine, / All wanting special little dishes.”10 Art ran in the family, if ever so feebly, and people were vaguely cosmopolitan. Violet’s parents, Ernest and Hilda Schuster, brought a combined tradition of German culture and Judaism into the family that certainly helped shape Spender’s own worldliness. In “The Ambitious Son,” a poem from Ruins and Visions (1942), Spender recalled a childhood overshadowed by the feeling that he was failing to live up to the family name. “My childhood went for rides on your wishes,” he told his father, now long dead:

As a beggar’s eye strides a tinsel horse,

And how I reeled before your windy lashes

Fit to drive a paper boat off its course!

Deep in my heart I learned this lesson

As well have never been born at all

As live through life and fail to impress on

Time, our family name, inch-tall.

The bitter irony palpable in that last line wasn’t available to Stephen when he was a child. As an adult, he remembers his childhood as dominated by the feeling of being lost “in a vast, deserted garden.” But although he had learned to see his father’s goals for what they really were, he had continued to live his life as if he still wanted to please him: “O Father, to a grave of fame I faithfully follow!”11

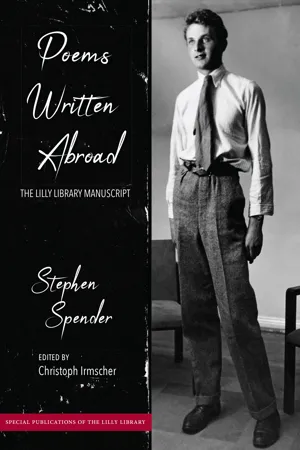

Figure 0.2. Stephen Spender, 1929. Unknown photographer. The Lilly Library.

Stephen’s mother, Violet, died when he was only ten, and Harold, discouraged by his lack of measurable political success, did not survive an operation on his spleen in 1926, accepting even before he went under the knife that he would die. In his autobiography, Stephen spoke of his own weakness, the lack of a “strong will,” as the curse of his life and the limitation that prevented him from achieving true greatness as a poet. But he also claimed that laziness was a way to rebel against his family and their emphasis on morality, work, and discipline. Young Stephen was an intense child, visited by nightmares and desires that overwhelmed him. His vivid imagination forced him to picture Christ fastened to the cross by ropes, because the thought of nails driven through his flesh was intolerable. In his autobiography, he likens his first experience of sexual pleasure, felt when wrestling with another boy, to a “sensation like the taste of a strong sweet honey … spreading wave upon wave, throughout my whole body.” The main fear his family had implanted in him was that of becoming a “moral outcast,” the fear that there might be residing in him some “final wickedness…, some unspeakable shame of ultimate depravity.” Yet, instead of resisting wickedness, he embraced it, a risky undertaking at a time when homosexuality was still considered a crime in England. But that would be entirely too easy a reading, as Spender himself recognized. In his autobiography, Spender called himself a “wanderer,” not a pilgrim—an acknowledgment that he was never quite sure what he was looking for.12

Many of the complexities of Stephen’s childhood and adolescence are memorably captured in a novel he drafted late in life, Miss Pangborne,13 a roman à clef told from the perspective of the nanny who was brought in to look after the orphaned Spender children and whose name, in real life, was Winifred Paine. As one biographer described her, Winifred became “a sort of Mary Poppins” to the Spender siblings and went on to cause a great deal of confusion to the adolescent Stephen.14 He appears in the novel as Martin Banner, a sensitive, artistically inclined youngster deeply interested in the sculptures of Jacob Epstein and the paintings of Augustus John, a passion considered immoral by his inefficient father “because of the nudes.”15

When she arrives, Miss Caroline Pangborne finds the Banner household in disarray and Martin/Stephen in mental distress, deeply affected by the fall of a previous live-in nanny, Susan Sled, from their house’s fourth floor. It appeared that Susan had become rather too attached to Martin’s father; luckily, she survived her impulsive window tumble.16 Right after, the traumatized Martin was sent to live for a while with his aloof grandmother, Mrs. Schelling (Hilda Schuster in real life), accompanying her to Quaker meetings, where she would invariably fall asleep. Mrs. Schelling tried to implant in Martin a fear of the consequences of sex (venereal disease) and a respect for class boundaries especially when it came to marriage. The novel draft also recounts a feverish dream in which Martin, carted off to the hospital for treatment of scarlet fever, sees himself floating above foggy London, high above the honking cars, roaring lorries, and pealing church bells until he finds himself entering a corridor of flames lined by Blakean figures, at the end of which he glimpsed the Light that was God. Or so he dreamed until he awoke, cured of his fever.17

The novel remains firmly anchored in Miss Pangborne’s consciousness, and it is through her eyes that we see Martin/Stephen, a remarkable feat of authorial self-detachment. Tall, angular, stooping slightly, Martin looks awkward, like a crane out of his element. His handshake is too soft, and he seems permanently distracted. His older brother Adam (i.e., Michael Spender) mercilessly mocks him for wearing an ill-fitting suit with vertical stripes that only emphasized his “verticality.” But despit...