![]()

![]()

The Aztecs arriving at the site of Tenochtitlán.

1 The Founding of Tenochtitlán

Ponder this, eagle and jaguar knights,

Though you are carved in jade, you will break;

Though you are made of gold, you will crack;

Even though you are a quetzal feather, you will wither.

We are not forever on this earth;

Only for a time are we here.

Nezahualcoyotl, the poet-ruler of the Acolhua

people living on the shores of Lake Texcoco

in the mid-fifteenth century

Before the coming of the Spaniards in the sixteenth century, before the arrival of the Mexica, or Aztecs, in the fourteenth century, a thriving population already lived in and around the five lakes to be found at the centre of the Valley of Mexico. Situated at over 2,000 metres (6,500 ft) above sea level, and more or less midway between the Pacific and Atlantic coasts, the valley is a vast hollow encircled by mountains, volcanoes and once dense forests. Millions of years ago, a volcanic eruption is thought to have thrown up mountains that cut off the rivers that flowed through the valley from their outlet to the Pacific Ocean, creating an enclosed natural system with both salt- and freshwater lakes. This valley was home to abundant wildlife and attracted early groups of hunter-gatherers. They settled around the lakes and on islands within them, living via fishing and agriculture. Mexican historians date the first settlements in the Valley of Mexico to more than 20,000 years ago.

Some 50 kilometres (30 mi.) outside today’s capital city, it has been estimated that between 25,000 and as many as 100,000 people lived in and around Teotihuacán (the Place of the Gods) before it was abandoned in the seventh or eighth century after what appears to have been a devastating fire. Nowadays it is one of the main tourist attractions to the northeast of Mexico City, with massive pyramids and temples at the centre of a site covering more than 20 square kilometres (7½ sq. mi.). Monumental buildings line the central axis of the Avenue of the Dead, perhaps the most spectacular of them being the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. This low pyramid has six levels, all decorated with stone heads that alternately show the Fire Serpent and the Plumed Serpent. But it is the huge Pyramid of the Sun that most tourists come to visit. This pyramid is some 70 metres (230 ft) high and 225 metres (740 ft) long, and is thought to have been built around the first century AD. Close by is the Pyramid of the Moon, with murals showing the Paradise of Tlaloc, the rain god, and others depicting the traditional ball game known as ollamalitzli, and human sacrifice.

As with many of the early civilizations of Mexico, the cause of the decline and fall of Teotihuacán remains unclear. Beyond the grandiose monuments, little is known of the lives and beliefs of its inhabitants. Following the collapse of the city, the Valley of Mexico saw the spread of much smaller centres of habitation, with many different groups coexisting or fighting for dominance.

It was not until several centuries later that the Aztecs came to exert their control over many of these existing groups. According to legend, the Aztecs were a nomadic people who in the thirteenth century migrated from their home of Aztlán (the Place of Herons), in the northwest of Mexico, to the Valley of Mexico. They were said to have followed a prophecy by their war god, Huitzilopochtli, that they should migrate towards a spot where they would find an eagle devouring a serpent on a nopal cactus rising from a rock (the image now in the centre of the red, white and green Mexican flag). The place they arrived at is thought to have been on the hill of Chapultepec (Hill of Grasshoppers). Freshwater springs nearby and the abundance of wildlife led the wandering Aztecs to settle there. This is said to have taken place in 1325, which is traditionally accepted as the date for the foundation of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán.

Cultivating maguey, from a map of Tenochtitlán, c. 1550.

Their settlement grew over the following generations, and by the fifteenth century the Aztecs began to expand, thanks mainly to their conquest of neighbouring indigenous groups. In around 1430 their armies defeated their main rivals, the Tepanecs, and they soon established an empire that extended far beyond the confines of the Valley of Mexico. With conquest came trade, including gold, silver, jade and other precious goods that underlined the splendour of Aztec rule. Over the next ninety years, the Aztecs expanded Tenochtitlán, on an island on the middle of Lake Texcoco, the largest of the interconnected lakes in the centre of the valley. The Aztec capital is thought to have contained anywhere between 100,000 and 250,000 inhabitants. To help feed this population living in the lakes and marshes, the ingenious system of chinampas was developed. These were small floating islands of mud and vegetation that provided extremely rich soil for cultivating vegetables and fruits. The diet of the Aztecs was chiefly composed of the maize, squashes, beans and chillies produced by this system, as well as the abundant fish from the lakes and game that roamed in the hills. Archaeologists have also found evidence that they ate snakes, iguanas, grasshoppers and other insects, worms, and the algae growing on the surface of the waters. They used canoes to get around the lakes, and the canals they created between the artificial islands allowed the inhabitants to transport themselves and their goods throughout the city with ease.

Tenochtitlán was connected to the lakeshore by three huge earthen causeways, which radiated out from the imperial palace at the heart of the city. A wall surrounded the central religious precinct, with basalt figures of jaguars at its base. Inside this wall stood many stone temples, built with pyramids on their summits that are said to have been a representation of the power of the volcanoes visible on the horizon. The different parts of the Aztec city were well defined, with straight roads and canals separating the different districts, which were divided according to the activities that took place there.

Although the Aztec rulers lived in magnificent palaces and the priests had no less splendid temples, most of the population of Tenochtitlán lived in wattle and daub huts with grass roofs. They slept on mats, kept a fire in the middle of the room and often decorated the land outside with flowers. They reared guacalotes, or turkeys; dogs and rabbits, which were frequently used to supplement their diet; and parrots and macaws for their feathers, which were used in cloaks and headdresses. In his book Daily Life of the Aztecs, the French ethnologist Jacques Soustelle provided a poetic description of how he imagined the day beginning for these ordinary inhabitants of the Aztec capital:

Cultivating maguey. An Aztec woman blows maize before putting it into the pot so it will not ‘fear’ the fire.

With their wicker fans the women blow on the fire that smoulders between the hearth-stones, and then, kneeling before the metlatl of volcanic stone they begin grinding the maize. The work of the day begins with this dull rumble of the grinder: it has begun like this for thousands of years. A little later comes the rhythmic slapping of the women gently flattening the maize-dough between their hands to make the pancake-like tortillas or tlaxcalli.

In addition to this everyday routine, a large part of life was devoted to keeping the more than two hundred deities in the Aztec pantheon happy, or at least to appeasing their wrath and maintaining stability on earth. In a land plagued by earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, the destructive power of the gods constantly seemed a threat. Perhaps this is why Aztec religious ceremonies often involved human sacrifice, especially to the two main gods, Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, and Tlaloc, the god of rain and agriculture. Usually the victims were prisoners captured during wars with neighbouring groups, although it seems that slaves and even Aztec children were also offered for sacrifice. Early in the sixteenth century one of the Spanish conquerors, Andrés de Tapia, calculated that there had been around 136,000 victims sacrificed at the Templo Mayor (Great Temple). As recently as 2017, archaeologists found proof that de Tapia’s story was not entirely invented, when they discovered a circular tower close to the temple encrusted with almost seven hundred skulls of men, women and children.

By the time the Spaniards arrived, the emperor of the Aztecs was Moctezuma II (the great-grandson of the ‘irascible prince’ Moctezuma I). As well as ruling over Tenochtitlán and the neighbouring lakeside towns, he controlled territory and exacted tributes as far away as what is now the Gulf of Mexico in the east. Although his rule appeared solid, and Aztec society built on firm foundations, there were disturbing portents that he could not ignore. The Aztec calendar was based on four different epochs, each represented by a different sun. But now, according to priestly calculations, the Aztecs were living in a fifth era, which was predicted to end in catastrophe, a twilight of the gods more terrible than Wagner’s.

The excavated Aztec Templo Mayor in the city centre.

TEMPLO MAYOR

At the heart of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán stood the Templo Mayor, or Great Temple. This is said to have been built on the spot where the Aztecs first saw the eagle devouring a serpent that was the sign for them to found their city. The temple is a stone representation of Coatepetl, the ‘Hill of Serpents’, the mythic birthplace of the Aztec world.

It was here that Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, defeated the moon goddess, Coyolxauhqui, whose dismembered body lay at the foot of the hill. Coatepetl was located at the navel of the Aztec world. The wide platform on which the twin temples were raised is said to represent the earth. Above it are thirteen tiers which symbolize the Aztecs’ thirteen heavens, while beneath it are nine levels that descend to Mictlan, where the dead reside.

The Templo Mayor was levelled in the final assault by Cortés in 1521. For more than four and a half centuries, it survived only in the written records of the conquerors and the painted codices of the defeated. Then, in February 1978, workers laying new electrical cables behind the cathedral in the northern corner of the Zócalo uncovered the edge of a round stone 3 metres (10 ft) in diameter. When the site was explored by archaeologists, the disc was revealed to be the image of the shattered body of Coyolxauhqui. Over the next four years the dig was extended. The terraces were carefully uncovered, and in them were found more than 6,000 statues, other ritual objects and sculptures and figures from as far distant as Oaxaca and the Gulf Coast.

Today the remains of the temple are visible from metal walkways, offering views of the terraces and the upper levels. A well-designed museum containing the finds from the archaeological digs is located above and behind the remains. Its centrepiece is the Coyolxauhqui stone, which can be seen on the same level and also from above, giving some idea of how it must have looked many centuries ago.

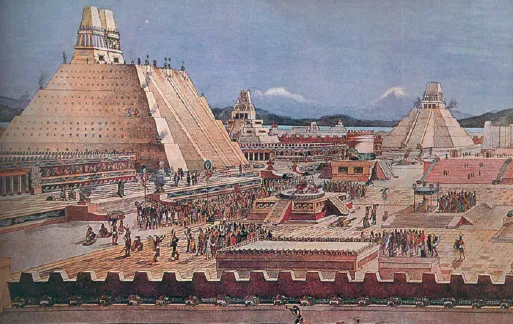

Artist’s impression of the ceremonial centre of Tenochtitlán.

Early in the 1500s, Moctezuma and his people began to receive reports of strange newcomers who had arrived on the coast to the east. These reports coincided with the passage of comets, storms and floods that seemed to presage disaster. Then in 1518 more definite news arrived (as recorded by Moctezuma II’s grandson, the historian Tezozomoc) that ‘two towers had been seen moving about on the sea off the coast’. Moreover, ‘the skins of these people are white, much more so than our skins are. All of them have long beards and hair down to their ears’. Moctezuma sent emissaries to exchange gifts with the newcomers, who then departed, promising to return.

A year later, in 1519, Cortés and his men landed. Moctezuma and his people were now faced with new and terrifying wonders. The strangers rode horses, beasts not previously known in the Americas. They carried their goods on wheeled carts – the wheel too was unknown to the indigenous populations. Other wheeled machines – the Spaniards’ cannons – fired balls that could destroy trees and the earth all around them, giving off smoke and a foul stench. Cortés was to write back to the Emperor Charles V in 1520 that Moctezuma accepted his authority because in their history the Aztecs had previously been ruled by Quetzalcoatl, a lord who had one day vanished, promising t...