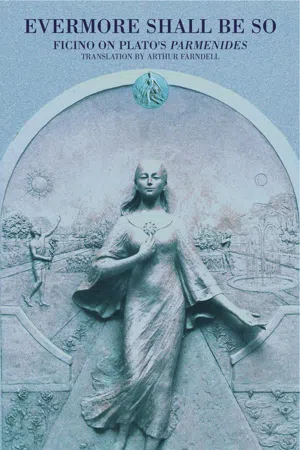

Evermore Shall Be So

About this book

Featuring philosophical commentary from Marsilio Ficino-a leading scholar of the Italian Renaissance who translated all the works of Plato into Latin-this work is the first English translation of Ficino's commentary of Plato's dialogue between the philosopher Parmenides and the youthful Socrates. In the scene, the older man instructs his student on the use of dialectic to draw the mind away from its preoccupation with the realm of matter and attract it towards contemplation of the soul.

"What made the Renaissance tick? Why had it such a force that its thinking spread from a small group of scholars in Florence, working in their own brilliant ways but coming together in a small villa on the Florentine hillside where Marsilio Ficino (143399) lived, to affect the thinking of the whole of Europe, and eventually of America, for five hundred years and is continuing to do so?

Cosimo de'Medici, the virtual ruler of Florence, had been attracted to the philosophy of Plato by Gemistos Plethon during the Council Florence in 1439 and had instructed his agents to gather together Plato's works before Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453. In 1462 he commissioned Marsilio Ficino to translate them from Greek into Latin for the benefit of the Latinspeaking world, a task he completed in under five years according to his biographer Giovanni Corsi.

This, the first volume in a four volume series, provides the first English translation of the 25 short commentaries on the dialogues and the 12 letters traditionally ascribed to Plato. Later volumes will provide translations of his longer commentaries on the Parmenides (2008), the Republic and Laws (2009) and Timaeus (2010).

Though this book will be an essential buy for Renaissance scholars and historians, its freshness of thought and wisdom are as relevant today as they ever were to inspire a new generation seeking spiritual and philosophical direction in their lives."

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

of Ficino’s Parmenides Commentary

Dedication to Niccolò Valori

‘Plato … has embraced all theology within Parmenides [Plato … universam in Parmenide complexus est theologiam].’‘He seems to have drawn this celestial work, in a divine way, from the deep recesses of the divine mind and from the innermost sanctuary of philosophy [videtur et ex divinae mentis adytis intimoque Philosophiae sacrario caeleste hoc opus divinitus deprompsisse]. Anyone approaching his sacred writings [Ad cuius sacram lectionem quisque accedet] should prepare himself with sobriety of soul and freedom of mind before daring to handle the mysteries of the celestial work [prius sobrietate animi mentisque libertate se preparet, quam attrectare mysteria caelestis operis audeat]. For here the divine Plato [Hic enim divinus Plato], speaking of the One Itself, discusses with great subtlety how the One Itself is the principle of all things [de ipso uno subtilissime disputat quemadmodum ipsum unum rerum omnium principium est]: how it is above all [super omnia], and all things come from it [omniaque ab illo]; how it is outside all and within all [Quo pacto ipsum extra omnia sit, et in omnibus]; and how all come out of it [omniaque ex illo], through it, and to it [per illud atque ad illud].’‘Parmenides … unfolds the whole principle of Ideas [Parmenides integram idearum explicat rationem].’Parmenides ‘introduces nine hypotheses [suppositiones] …, five on the basis that the One exists and four on the basis that the One does not exist.’Ficino gives a brief statement on the nature of each hypothesis, and he points out that Parmenides’ main intention is to affirm that ‘there is a single principle [principium] of all things, and if that is in place everything is in place, but if it be removed everything perishes.’The first hypothesis ‘discusses the one supreme God [de uno supremoque Deo disserit].’The second ‘discusses the individual orders of the divinities [de singulis Deorum ordinibus].’The third ‘discusses divine souls [de divinis animis].’The fourth ‘discusses those which come into being in the region which surrounds matter [de iis, quae circa materiam fiunt].’The fifth ‘discusses primal matter [de materia prima].’

‘Under the guise of a dialectical and, as it were, logical game aimed at training the intelligence [sub ludo quodam dialectico et quasi logico exercitaturo videlicet ingenium], Plato points towards divine teachings and many aspects of theology [ad divina dogmata passim theologica multa significat.]’‘The subject matter of this Parmenides is particularly theological [Materia … Parmenidis huius potissimum theologica est] and its form particularly logical [forma vero praecipue logica].’

A request is made for a previous discussion involving Parmenides, Zeno, and Socrates to be recounted.

‘The universe, or the all [universum sive omne] is appreciated in these three ways [tribus his modis accipitur]: individually, collectively, as a whole [singulatim, congregatim, summatim].’‘Beyond that unity which partakes perfectly of the intelligible world [praeter unitatem illam intelligibili mundo perfecte participatam] he (Parmenides) postulates a supreme unity [eminentissimam excogitat unitatem] higher than the one universal being [universo ente uno excelsiorem], for the nature of being is different from the nature of unity [alia enim ipsius entis, alia unitatis ipsius ratio est].’‘Therefore the one being [Unum igitur ens] is not the simple One Itself [non est ipsum simpliciter unum] but is in all respects a composite [sed quoquomodo compositum] mixed with multiplicity [multitudinique permixtum].’

Zeno, Parmenides’ disciple, confirms his master’s proposition with another, ‘whereby he shows that beings are not many [ens non esse multa], that is, not only many [id est, solum multa], but beyond their multiplicity [sed praeter multitudinem] they partake of unity [esse partecipes unitatis].’

‘Human nature depends on the Idea of man [ab idea hominis humana natura (dependet)].’‘Now the cause which is unmoving and universal at the same time [Causa vero immobilis simul universalisque] is necessarily the intellect [necessario est intellectus] and the intellectual Idea [et intellectualis idea].’‘Again, there are many Ideas [Ideae rursus multae sunt], as least as many as the types of natural phenomena [quod saltem rerum species naturalium], and each one is called a unity [et unaquaeque unitas appellatur], I mean, not simply unity [unitas inquam non simpliciter], but a unity [imo quaedam].’‘For this reason [quamobrem] there exists above ideal unities [super ideales unitates extat] the One that is simply itself [ipsum simpliciter unum], governing the full expansion of all species [per quaslibet multitudines latissime regnans].’

‘Since Ideas are eternal and intellectual in their extreme purity [Ideae cum sint aeternae et ad puritatis summum intellectuales], they produce within the same sequence beneath them unmoving and pure effects prior to moving and impure effects [effectus procreant in eadem sub ipsis serie stabiles atque puros, priusquam mobiles et impuros].’

‘There is a single Idea for the whole of a single type [unius communiter speciei una est idea].’

‘One is prior to multiplicity [unum antecedit multitudinem].’

‘God Himself is every Idea [quaelibet … idea est ipse Deus].’

‘There is no Idea for mud [Non est idea luti], but there is an Idea for water and for earth [sed aquae terraeque idea].’

‘The ideal causes [Ideales … rationes] are in the intellect of the Maker [in conditore sunt intellectu] and also in the world-soul [et in ipsa mundi anima] and in universal nature [et in universali natura].’

‘Nothing in our world [Nulla quidem rerum nostrarum] apprehends the whole power of an Idea [totam capit ideae virtutem]: that eternal, effective, and totally indivisible essence, perfect life, and perfect intelligence [scilicet aeternam illam efficaciam individuam prorsus essentiam, vitam intelligentiamque perfectam].’

‘Let us consider ideal equality [consideramus idealem aequalitatem]: an intellectual ratio [scilicet rationem quandam intellectualem] which is both a model and a unifier [tam exemplarem, quam conciliatricem] of universal harmony [universae congruitatis] and of harmonic proportion [et proportionis harmonicae] and of any kind of equality [aequalitatisque cuiuslibet].’

‘It is clearly the case [plane constat] that Ideas are remote from [illas procul ab] all differentiation, all place, all movement, and all time [omni divisione, loco, motu, tempore esse], being indivisible, unmoving, eternal, and present everywhere [impartibiles, immobiles, aeternas, ubique praesentes]: so present [ita praesentes] that each quality of an Idea [ut cuiuslibet ideae proprietas quaedam] extends to the uttermost ends of creation [ad ultimas perveniat mundi formas].’‘However, it is important now to remember [Meminisse vero nunc oportet] that forms in the physical world [formas in materia] are not produced directly from Ideas, but are made through the seed-powers of nature derived from Ideas [non proxime ab ideis, sed per vires seminales naturae illinc infusas effici].’

‘We use reason aright to take physical things back to their non-physical causes [resque corporeas ad incorporeas causas recta ratione reducimus].’

‘Just as true sense [quemadmodum verus sensus] focuses on something perceptible [circa sensibile quiddam versatur] which actually exists [quod et revera existit], which is prior to sense [et antecedit sensum], and which is united with sense at the time of perception [ac denique cum sensu iam sentiente coniungitur], so true intelligence [sic intelligentia vera], which he now calls notion [quam nunc nominat notionem], is directed towards something that is intelligible to it [ad intelligibile suum dirigitur], that really exists and is prior to it [revera existens atque praecedens], and is more united with notion [et magis cum notione coniunctum] than the perceptible is with sense [quam cum sensu sensibile].’

‘This universe has taken its rise not so much from the intellect or the intelligence as from intelligible things, namely, the first essence, which is full of intelligible types and powers [universum hoc non tam ab intellectu vel intelligentia quam ab intelligibilibus, id est, ab essentia prima intelligibilium specierum virtutumque plena].’

‘The nature of the Idea is not conveyed to our world [neque ipsa ideae natura ad haec nostra transfertur], nor, conversely, do the things of our world in any way meet Ideas [neque haec igitur in re ulla conveniunt cum ideis], but merely reflect them [sed solum illas referunt], just as the image in a mirror reflects the face [quemadmodum specularis imago vultum].’

Table of contents

- Cover

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Translators Introduction

- An Overview of Ficino’s Parmenides Commentary

- Glossary

- Name Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app