![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Earliest Civilizations in Mesopotamia and Egypt

Why Did They Appear? (The Challenge of the Land)

Recently, there has been an interesting and innovative approach to history by presenting human history in the larger context of the history of the universe. In “big history” the authors have tried to include the event of the Big Bang and the subsequent geological and biological development on Earth as a necessary component of explaining human history on Earth. The present work, in the spirit of this larger vision, albeit much more philosophically inclined, attempts to integrate the achievement of modern sciences from the Big Bang to general relativity and quantum physics in one human history—or at least part of humanity’s intellectual history. We will later examine how this recent understanding of the universe impacts our interpretation of the meaning of human history.

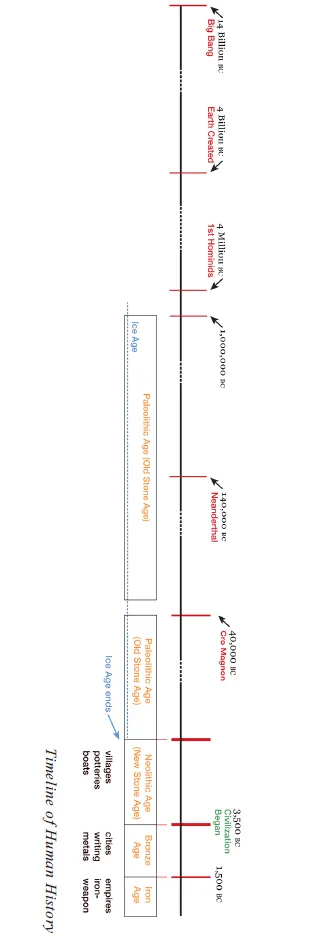

Let us take a quick look at what today’s science tells us about the beginning of “time” as we know it. The Big Bang, or the moment of creation of the universe, happened some 13.7 billion years ago. The Earth was created around five billion years ago (roughly two-thirds of the way back in time), but the remains of the oldest humanlike creature (Lucy) are known from only as far back as about 3.7 million years (remember that a billion is one thousand million), which is a very short time considering the age of the universe. The appearance of the oldest civilizations, the Sumerians and the Egyptians (5,500 years ago), is far more recent than that. If we consider the life of the universe as one year, these oldest of all civilizations appeared just a few seconds before midnight on December 31.

Until just a few decades ago, scientists believed that the universe always existed. Eternity was the perceived status of the universe. The Big Bang theory, now increasingly supported by scientific evidence, has replaced that view with a much broader view that includes not only the evolution of species as discovered by Darwin but also an evolutionary view toward all of existence. In the new cosmology, as scientists try to uncover the physical laws governing moments closer and closer to the instant of the Big Bang, they increasingly enter the realm of philosophical speculation as opposed to mere science. The understanding of the history of the universe cannot be separated from the understanding of the philosophy of existence. The urge to retry in light of the new scientific paradigm is irresistible.

On the other hand, in the super-small quantum level of reality, the statistical nature of particle movement (as opposed to a rational cause-and-effect nature) has opened the possibility of ultimate indeterminism in nature. Human beings, with the grayish matter called the brain, which is part of this physical universe, could well have a free will unexplained by science. Leaping into the social science explanation of human history, with the long approach of social historians (historians acting as sociologists), the fundamental understanding of historical explanation might have to be revised to include a directional urge toward a more historically advanced humanity. I am well aware that the previous era’s historicism and altruism have come to an end after leading to various types of authoritarianism, all in the name of historical truth. However, considering history as a series of meaningless and random events has devalued our lives to where we have become empty observers and neutral explainers, allowing fanatics of all types to fill the vacuum. Einstein’s relativity theory has been misinterpreted and has led to social relativism in much the same way Darwinism has been misconstrued to create social Darwinism.

How does all of this new information impact my telling of the story of humanity? Quite simply. Every so often, human societies have faced grave challenges. In spite of all the conditions and limitations imposed on them, their free choice of a creative, new vision that included all the past and went beyond all the present conflict moved humanity into a higher orbit of intellectual and material advancement. We are facing such a moment at this time in global history. In medieval times, petty divisions between Catholics and Protestants ended with a new vision of nationalism after more than a hundred years of bloodshed. A new, larger nationalism, as a new vision and new transcendence, corrupted itself with racial nationalism and led to the two bloodiest wars in human history (WWI and WWII). New socialism failed to bring the promised human unity. Now, in a new cycle back to religious transcendence, humanity is facing a new challenge, this one much graver and potentially more destructive than anything human beings have seen in the past. Only with awareness and a vision that includes all past religious beliefs can we minimize the damage and pass through this time into a bright, new future. It will not happen automatically; it depends on our collective free will.

1. PREHISTORIC PERIOD

Most historians refer to the period of time before the rise of writing systems, around 3500 BCE—which also coincides with the rise of the first human civilization in Mesopotamia, the Sumerian civilization—as the prehistoric period. Technically, this is a time before we can even talk about human history. However, because everything is related, in presenting human history, we shall begin with a brief description of these earliest human beings in prehistory from the hunting and gathering stage of the Paleolithic Age to the first human settlements in the Neolithic Age.

a. Paleolithic Age (One Million to Ten Thousand Years Ago)

There have been many ice ages in the life of the Earth. The last one started around one million years ago and ended about ten thousand years ago. The end of the last ice age coincided with a major revolution in human life, called the Neolithic Age, which included the Agricultural Revolution (the beginning of agriculture) and the domestication of animals, the two earliest steps of human beings to control nature. We will discuss the significance of this revolution later in our discussion of the Neolithic Age.

Let us now go back to the time before the last ice age and look at the evolution of our species. As we said, the oldest hominid discovered so far dates back to 3.7 million years and was found in Africa. It is a body of a short woman whom anthropologists call “Lucy.” Moving on through history for another few hundred thousand years to around 150,000 years ago, we come to another major discovery: the Neanderthals, who are not quite “us.” The most amazing discovery from this time is a Neanderthal gravesite. They not only buried their dead but also decorated the bodies with flowers. Even more fascinating and telling about who they were and what they thought is that they buried tools along with the dead. What do you think that tells us about the Neanderthals? They were thinking about life and death and what happens after death. In other words, they were philosophical beings, just like us. As far as we know, no other creature does that. They believed there is life after death, which is why they laid the tools with the bodies, to be used in the afterlife. They respected death, as indicated by their adornment with flowers. Only human beings do that.

If you recall, we are still in the Ice Age or the Neolithic Age. From around forty thousand years ago, we have found the first traces of our species, homo sapiens sapiens, also known as Cro-Magnon or modern man. The earliest findings from our species are some small statuettes dating to about 25,000 BCE. They are all female figures with large hips and breasts, collectively called Venus of Willendorf (see photo). Why do you think these statuettes were made? Were they decorative figures? Were they toys for their children? Were they sex enhancement objects?

From what we can speculate, their function was none of the above. These objects had religious significance and were goddesses. The female body produces life; women nourish and sustain life. These statuettes were perhaps paths to communicate with the forces of nature in the hope that they would give them the blessings of fertility and therefore guarantee the survival of the group or the tribe.

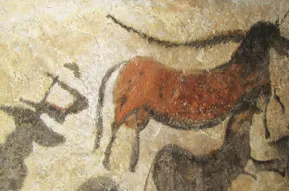

Moving in time to around 13,000 BCE, we find some extraordinary archeological findings in a major cave network in Lascaux in southern France, with beautiful cave paintings (see images). In these huge and dark caves, we have discovered large paintings, images of wild animals such as horses, bulls, oxen, and other hunted animals, some showing arrows piercing their bodies. Why did these humans paint these images? What was the significance of these paintings? Were they done to pass the time? Were they instructions for how to hunt? Were they just decorations and for pleasure?

The most plausible answer, based on what we know of other recent prime cultures we find today in Africa, South America, and Asia, is that these paintings had important religious significance and piercing might have served similar function as the more recent voodoo practice in South America. Considering the time these paintings were done (before the Agricultural Revolution and the domestication of animals) and that the lives and survival of these people depended solely on a successful hunt, we can appreciate the religious value of these images. This was also a way to communicate with the forces of nature at a time when the divine had not been separated from natural and supernatural forces. This respect for nature, long forgotten when later dogmas taught us to believe we are here to dominate (and even destroy) nature, not to live in harmony with it, could have been seen until recently, for example, in the Native Americans’ treatment of nature and appreciation of what it gives them.

You might have heard of the “buffalo dance” in which the natives would embark on a hunting mission with ceremony, music, and dance. When they succeeded and brought back their gift of nature, they treated the animals as though they were escorting a dignitary into the village, also with music and dance, not just to show how happy they were but to also thank nature for the blessing.

This brings us to the important notion of the most basic definition of religion. In the most general sense, one can say religion is about survival. From these early and primitive cultures to the modern Christian faith, in which faith in God guarantees eternal life in heaven, we see this deep and fundamental human yearning for survival. Egyptians longed for it too when they built the magnificent pyramids to preserve the bodies of their pharaohs, equipping the tomb with everything he or she might need in the next life. The only major difference between these early religions and later more sophisticated ones is the rigidity of their dogmas, the later religions creating the concept that humans are separate from nature.

b. Neolithic Age (Ten Thousand to 5,500 Years Ago) The Age of the Agricultural Revolution and the Domestication of Animals

As we mentioned earlier, the Paleolithic Age (New Stone Age) corresponded to the last ice age, which lasted from about one million to about ten thousand years ago (or 8000 BCE). Perhaps as a result of the melting of the ice and exposure of the dry land, the end of this ice age produced the opportunity for agriculture. This in turn resulted in a profound transformation in the way human beings lived and set the stage for more rapid cultural development. With the start of the Neolithic Age, the tribes, instead of moving around all day and spending the energy of all the members to find nuts and fruits or meat, began to settle down in villages (they no longer needed to be in caves because of the warming of the climate at the end of the last ice age).

In addition, instead of chasing animals for their meat, milk, and skin, they brought them inside fences and raised them close to their huts. These major steps in controlling nature worked well in freeing a surplus of human energy (and therefore a surplus of time) and led to a major creative expansion. Building huts and boats and making pottery, along with specialization of religion by some members of the group who claimed to have the power to communicate with the forces of nature, set the foundation for the first civilizations, which came about five thousand years later (see the timeline).

2. BRONZE AGE (3500-1500 BCE) THE BEGINNING OF CIVILIZATION

Most of this chapter focuses on the first civilizations in Mesopotamia and Egypt. These two civilizations both appeared in a very challenging environment—hot, arid, with little rain or natural vegetation. The soil in these two areas was agriculturally productive. With the increase in population at the edge of the water and competition for land, the major choice these humans faced was either to fight and kill each other off or cooperate and increasingly organize to create a sophisticated political organization to carry out the immense task of building larger and larger irrigation canals to carry the water inland. They chose the latter—to cooperate for the good of all. With a large population came the need for developing science, math, and technology much of which are the basis of our science and technology today. In short, the challenge was hard, but the reward was great: They gave humanity the gift of the first two civilizations and all their lasting impacts.

These two civilizations were a major step in the development of human society, and by far the most dramatic change came with the formation of political systems; social stratification (creation of social classes); the beginning of the first writing system; and, as the name of this age implies, the first use of metal— bronze—for tools and weapons. Ironically, the first civilizations appeared in the least likely places where, in general, there was little rain or natural vegetation growth. In examining the first four major civilizations, Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and China, we observe interesting similarities. All four faced the challenge of the shortage of agricultural water. There was not much natural moisture from rain and, therefore, not much natural vegetation, such as one might find in Europe or Hawaii. Ironically, these four earliest civilizations in human history all began in geographic and climatic conditions that were more desertlike, and therefore harder to live in, compared to many other parts of the world where there is more natural greenery and milder conditions. Throughout this book we will also see why different types of challenges facing different groups of humanity, if res...