![]()

PART ONE

Intercultural Dialogues

![]()

CAROL BROWN

So, Remember the Liquid Ground

We are grounded in a relationship with the environment which is changing constantly, what is coming into the present is us and the environment … in conversation.

(Gill Clarke in Lee & Davies [2011])

Standing on a beach, at the gifting line,

the receding tide leaves its debris of shells, seaweeds, fish

bone, and jellyfish

and the discarded waste of human lives

plastic bottles and wrappings, fragments of ceramics and

shards of sea smoothed glass

Feet sink into coarse-grained sand

Like sponges

Incoming water pools around toes

a wintery wind blows the foam caps off incoming waves

Face to sea and horizon line extending

Roaring, scudding saltwater

The same as the tears in our eyes

Before me, the shimmer of an obsidian sea

And behind me, the reflective glint of a grid of honeycombed windows

Polaroids at the ready, the glare-stare of the city meets the

sea

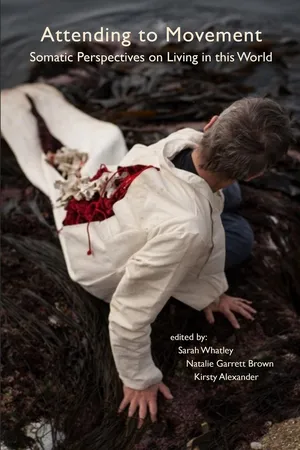

Fig. 1: Becca Wood, 1000 Lovers, Auckland, 2013. Photo: Cathy Carter

Knowledge of a sea like knowledge of a city, its patterns and pulses, its rhythms and riptides comes from embodied experience – I can study oceanography but I need the choreography of encounter to make sense of it – it is through practices like sea swimming and urban navigation that my knowledge of the unpredictability, changeability and readability of the environments we inhabit becomes incorporated.

In living in a city surrounded by sea – Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand – it is impossible to ignore the circadian rhythms of our cosmos as the time of the sea, its incoming and outgoing rhythms expressed as a twelve-hour tidal flow, forms a counterpoint to the quotidian patterns of urban life. As a choreographer, I have had a long-standing preoccupation with working with the kinaesthetic sense of a liminal threshold between water and land. From early attempts at choreographing the shifting push/pull of tidal rhythms as a metaphor for love in the duet O Seaswell of Love (University of Otago, 1984); to Manuhiri with Bronwyn Judge inspired in part by the long breaking surf swells at Kaitiaki Beach in North Otago (Dunedin, 1990); to Ocean Skin (The Place Theatre, London, 1997), a solo with video monitor and film of myself submerged in a bottomless pool; to the development of a constantly evolving virtual sea in SeaUnSea (Dance Umbrella, 2006), a real-time interactive performance and installation premiered at Siobhan Davies Studios; and that same year Deep and Beneath (2006) at the Roundhouse with an inter-disciplinary team of artists and young people in response to Cunningham Dance Company’s presentations of Ocean, dances in dialogue with a sense of the sea have been a longstanding preoccupation. The sea has made a good dance partner. Most recently, this preoccupation has emerged in a series of urban performances that navigate the fluid borders of the edge of the land in Auckland, a city built on a narrow isthmus between two harbours. The works, Blood of Trees (World Water Day, 2012); 1000 Lovers (Auckland Arts Festival, 2013); and Tuna Mau (Oceanic Performance Biennale, 2013) are variations of a performance cycle initiated in Perth in Western Australia through Tongues of Stone (Perth Dancing City, 2011). As an extended performance research event in collaboration with designer Dorita Hannah, sound artist Russell Scoones and local dancers in Perth and Auckland, these choreographies have been developed through a sustained attention to patterns of movement between bodies, cities, histories and nature.

As choreographer, water has not just formed a conceptual trigger and thematic content for these works but also provided me with rich kinaesthetic material through strong corporeal memories of a childhood spent sea swimming, lifesaving, surfing and diving. At a somatic level thoughts of the sea bring to mind the primacy of our own corporeal history in the internal sea of the amniotic fluids and in the inter-cellular processes of breathing. But the shifting edge of where the sea meets the land is also an inestimable, indefinable contour that constantly changes and shifts, like the outline of a body.

Politically, in the 21st century, water as an elemental force of nature has become mired in issues of scarcity and management. When the Conservative government came to power in the UK in 1979, water changed from being understood as a common good to becoming a commodity. Ten years later water was offered for sale to a public that already owned it collectively (Ward in Strang 2004: 10). Historical analyses of water resource management in the UK and elsewhere reveal a consistent pattern of lost agency and ownership. In Aotearoa New Zealand issues of water ownership and management are characterised by multiple languages, two distinct ones are those of indigenous and European cultures. For the former, wai or water is co-extensive with human life, is life giving and healing, a carrier of meanings, of stories and of mauri (spirit). For the European settlers who colonised New Zealand, water was understood as a resource to be drained, managed, channelled and systematically controlled or, alternatively, as a source of leisure for bathing, surfing, boating and swimming.

What if paying attention to the fluid membranes of our bodies, to the liquid ground of our beginnings, to the connection between the salt of our tears and the salt of the sea, to the pathways to and from as well as along the shifting edge of the sea formed the basis for a choreography that navigates between the diverse histories and meanings of water and convenes a relationship between that which is considered fluid and that which is considered grounded?

This writing refracts recent work in the field of urban performance in Aotearoa New Zealand at the quick edge where the sea and land meet, with notions of repair and concepts of space and materiality emerging in recent critical thought.

Fig. 2: Sophie Williams, 1000 Lovers, Auckland, 2013. Photo: Carol Brown

what can urban performance do?

For innovation in creative work, we need inhabitation – of our bodies, of the places we live and love, and of the ideas we want to bring responsibly back to community.

(Andrea Olsen 2014: 3)

The way I move is an ongoing response to what is around me. I feel, we feel, the force of movement take form in the thresholds of choreographic thinking. Knowing the world means paying attention to it, its reverberations, its textures, its colours and its patterns. Worlding this knowing through the choreography of encounter means inviting others to pay attention too.

Dancing in dialogue with the forces of the world in sensuous landscapes, urban terrains and civic sites holds the potential for transforming the sensory impulses of the body into performative moments that allow the forces and textures of the world to be re-embodied and invested with meaning and significance whilst at the same time drawing attention to the material dimensions of non-organic life, including water.

Performing Mnemosyne in Prague (Prague Quadrenniale 2011), I carry a bucket of water. Holding it aloft between me and visitors to the gallery I take the hands of strangers and carefully rinse them in the water before touching my head with their hands. Hand, head and heart form a nexus of contact in this moment, momentarily a language of touch creates a constellation of meaning within the quotidian environment.

Fig. 3: Carol Brown, Mnemosyne, Prague Quadrenniale, 2011. Photo: Russell Scoones

In Perth, Catherine Piue performing as ‘sloshy’ manages two buckets of water and a harness of water-filled balloons. The task of carrying water in multiple containers is heavy, cumbersome and makes her stagger as she moves down the lane. An impossible task, balloon sacs drop and break on the paving stones, their split membranes releasing a small flood of water that the audience navigate around as they journey behind her. The sacs become grotesque bladders, organs of release that leak and spill.

Fig. 4: Catherine Piue, Tongues of Stone, Perth, 2011. Photo: Christophe Canato

new forms of agency

As a choreographer I see performance as holding the potential to intensify the experience of sensation, both subtly and spectacularly. In the context of site-responsive performance this occurs by drawing attention to the co-presence of the human and the non-human across a relational field of joint agency. Reflecting on each of the choreographed situations above, I note that their ‘taking place’ is predicated upon a watery threshold that forms a liminal space of encounter with bystanders.

As these instances of performances indicate, I am interested in choreographic practices that return us to our animal lineage and to the sensuality of the environments we inhabit: practices that are not purely bound up with concepts but reside in our capacities to be attuned to material life. In passing from nature to culture, from the satisfaction of instinctual needs to the sharing of desires, these dances in public spaces are in part formed by a desire to bring beings and non-beings into relation. In other words they are concerned with moving beyond the anthropocentric.

This concern follows the work of French feminist philosopher Luce Irigaray (2012) who, like Elizabeth Grosz, calls for a new epoch in our human evolution, an era in which art, philosophy and spirituality are endowed with meaning and put into a practice in ways different from those that we have known in the past (2012: 22).

A chorus of ‘river-runners’ holding stainless steel buckets filled with water run through busy urban streets. The water sloshes and spills over the side of the buckets splashing onto the pavement and disrupting passers-by.

Fig. 5: River Runners, STRUT Dance, Tongues of Stone, 2011. Photo: Christophe Canato

If dance is a place I go to, to know myself, my surroundings and environment, what is it to form a sense of place through liquid ground? For Luce Irigaray, a forgetting of air and of fluids is part of our inheritance of Western philosophical thought. In her recent writing she describes a loss of sensory intelligence in our relations with nature and the other; and that we are trying to find it again:

I think that we are trying to find the crossroads at which we have taken the wrong path. (Irigaray 2012: 145)

If Western philosophy has historically denied the sensory intelligence of the body, so too has the so-called ‘civilising’ influence of industrial economies in their relationship to resources. Paul Carter describes this legacy as ‘dry thinking’ that held an aversion to the damp, humid, sodden and swampy.

The history of Western civilisation is a history of desiccation. All civilisations require water, and many are literally built upon it. But modern Western cultures have defined themselves increasingly by setting water apart, as a necessary, but foreign object or resource, rather than as a constituent and accomplice of human life. European culture has grown ever more suspicious of the moist and damp. (Carter 2005: 107)

And yet, our bodies are composed primarily of fluid. The cells of our tissues live within the interstitial fluid, our internal sea. As Emilie Conrad described it, ‘we are basically fluid beings that have arrived on land’ (cited in Olsen 2014: 13). A denial of the damp, the leaky and the fluid is part of a long legacy of somatophobia in the West. Overcoming this denial, paying attention to the wetness of our eyes, the moisture in our mouths and lips, forms part of a movement towards a more visceral and corporeal state of awareness and way of knowing.

Is the source of your movement arising from the effortless internal flow of fluid through your tissues or is it restricted due to hardness, dryness, stagnation, collapse or stress and effort? Body-Mind Centering is a practice that focuses on the movement of the body’s fluids acknowledging and opening the potential for blood, lymph, cellular, interstitial and cerebral-spinal fluids. Each fluid has a specific rhythm and tonal range. According to Body-Mind Centering techniques the mind of the fluids is flow, rhythm and ease in the ever-changing conditions of our lives including in relation to environment.

On Munster Lane a chorus of river-runners ...