![]()

Chapter 1

Inflation: Why So Low For So Long

Blu Putnam & Erik Norland1

Editor’s Note: As the economic expansion in the US after the Great Recession of 2008–2009 chugged along, as millions of new jobs were created, as the Federal Reserve embarked on massive asset purchases and held short‐term rates near zero, both monetarist and labor market economists were confounded by the lack of more inflation. This essay explores the heroic assumptions in their models and tracks the changing state of the regulatory framework, not to mention how technology has altered how money changes hands, to explain the failure of many popular theories to explain or anticipate inflation patterns correctly. – KT

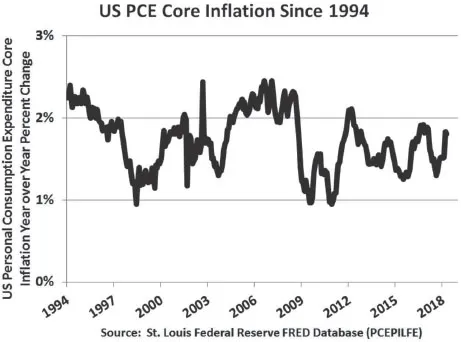

US inflation has been subdued for well over two decades, as in all the major, mature industrial economies. This is not a recent phenomenon, and is not due to the lagged impact of the 2008 financial panic. Indeed, whether measured by the consumer price index (CPI) or the Federal Reserve’s (Fed’s) favorite personal consumption price deflator (PCE), core inflation, which excludes the more volatile food and energy categories, has been stuck in a 1% to 3% range in the US since 1994 and into 2018.

Figure 1‐1: US Inflation

During this 25‐year period of subdued inflation in the US, there were two big cycles in unemployment; a stock market technology rally and tech wreck; a housing boom and massive housing recession; short‐term rates above 5% as well as near zero; plus, some massive Fed experiments with unconventional monetary policy (i.e., asset purchases or quantitative easing, QE). Thus, to evaluate different scenarios for inflation, analysts need to step back and examine the underlying causes of more than two decades of subdued inflation. And, in so doing, we will look at several simplified theories of inflation forecasting. By examining the often heroic (and incorrect) assumptions, we will get an improved sense of why most inflation theories totally failed to have any predictive value.

Our central thesis comes straight from basic economics: price rises (i.e., inflation) occur when spending demand exceeds the supply of goods and services. As we take a tour of various approaches to inflation forecasting, we will be highlighting the changing patterns in the demand for spending or the supply of goods and services. A common theme will be that structural changes in our information‐age economy have vastly changed how spending demand is created and how goods and services are supplied. And the results of these information‐age pattern shifts effectively rendered virtually all the simplified inflation forecasting approaches useless.

Monetary Policy Is Now More Limited In Its Ability to Encourage Growth

In the 1950s and 1960s, Professor Milton Friedman of the University of Chicago became famous for his research on money supply as the primary cause of inflation, even if the lags in monetary policy were long and variable. The monetarist theory of inflation fit the inflation data exceptionally well during the 1960s and 1970s, but it fell apart in the late 1980s and never regained empirical support in later decades.

What went awry with the monetarist theory? The assumed relationship between money supply and spending demand totally broke down. Back in the 1950s, if one wanted to buy goods or services, one paid with cash or with a check drawn on a basic bank account that paid no interest. There were savings accounts in the 1950s, yet they did not have check‐writing privileges. Credit card use was minimal and the ability to borrow through a credit card was constrained. The ability to move funds instantly and efficiently from investment accounts to payment accounts was a dream. Neither cash management nor brokerage accounts allowed check writing. The ability to transfer money over the internet or with a smart phone was not possible. In this bygone era, the money supply was very tightly correlated to spending, and thus rapid increases in the money supply served as a good predictor of future spending and future inflation, assuming the supply of goods and services was constrained to grow at a slower rate than the money supply growth.

The 1980s and subsequent decades ushered in massive changes in the way spending demand was created and severed the link with any and all measures of the money supply. Checking accounts could pay interest. Checks could be written on brokerage accounts. Credit cards came with lines of credit to be used (up to a limit) at the discretion of the spender. These changes in how spending was facilitated alone were enough to destroy the correlation of money supply measures with inflation, and the Fed stopped setting money supply target ranges in the late 1980s. Then came the 1990s and subsequent decades. The information age brought a myriad of ways to transfer money and manage credit, with smart phones and internet.

The story does not stop here, though. Even if the measured money supply was no longer a good predictor of future inflation, one might still expect interest rate policy or quantitative easing to have an influence on future inflation. Yet, neither interest rate policy nor central bank asset purchases produced any evidence of correlation with inflation over the two and a half decades, starting in 1994.

There seems to have been two critical forces at work that contributed to the lack of influence of monetary policy over inflation and the real economy since the early 1990s. The first was increased prudential bank regulation focused on capital requirements, and the second is the rise of sophisticated interest rate risk management in the financial sector.

When banks and other lending institutions are capital constrained by prudential regulations, they are unable to expand credit, which could drive spending demand. Even if short‐term interest rates are relatively low and below the prevailing inflation rate, credit growth may be constrained by capital requirements. Even if the Fed buys massive quantities of US Treasury and mortgage‐backed securities, bank lending may be constrained by capital requirements. The rise of prudential regulation to safeguard the financial system, which gained substantial momentum after the collapse of savings and loan institutions in the recession of 1990–1991, had the unintended consequence of making monetary policy less effective in terms of inflation management. As the policy pendulum swung toward bank regulation and reducing systematic risk, the influence of central bank macro‐economic tools waned. The embedded assumption made by most academic economists in their macro‐economic models that the policy environment is stable and has no influence on the efficacy of monetary policy could not have been more wrong.

The Savings & Loan (S&L) crisis of 1990–1991 also had another impact. S&Ls were basically institutions that borrowed short‐term (savings accounts) and lent longer‐term (home mortgages and later high yield debt). They took on substantial interest rate risk, and many S&Ls did not hedge or otherwise manage that risk — earning the premium for taking the risk of maturity intermediation was an integral part of their business model. After the S&L crisis there were effectively no financial institutions of any importance left in the US economy that did not adopt sophisticated interest rate risk management processes.

One of the interesting consequences of improved interest rate risk management in the financial sector is that the profitability of financial institutions would be less impacted by small changes in interest rate policy. That is, small changes in Fed interest rate policy would no longer impact financial sector profitability.

With interest‐rate risk being more effectively managed, the big risk left on the books of financial institutions was credit risk. That is, the risk of a recession that substantially diminishes the credit quality of bank loan portfolios. And even in the credit risk sector, financial institutions over the decades vastly improved their ability to assess and manage credit risk — not enough to handle a deep recession, such as 2008–2009, but effective credit risk management does limit the ability of the Fed to tap the brakes or hit the accelerator to influence the real economic growth.

Make no mistake, if the Fed were to raise short‐term interests sharply above the prevailing rate of inflation, the Fed could, no doubt, trigger a recession, but macro‐economic management and fine‐tuning has become less and less possible. This latter point illustrates some of the asymmetry in Fed policy outcomes. The Fed can still cause a recession by tightening too much — often measured by the shape of the yield curve. When short‐term rates are equal to long‐term bond yields (flat yield curve) or when short‐term rates are set above long‐term bond yields (inverted yield curve), recessions often follow in one or two years. The other side does not work so well any more. Near‐zero rates and asset purchases can raise equity and bond prices above what they otherwise would have been, but the impact on the real economy and inflation is virtually non‐existent. Put another way, the Fed can still create asset price inflation, as it did in the 2010–2016 period of emergency low rates and QE, but the Fed has very limited ability to encourage more growth in an economy that is already creating jobs at a good pace. [See Chapter 4 for an in‐depth analysis of why we believe a relatively flat or inverted yield curve remains an excellent indicator of future economic deceleration even if highly positively‐sloped yield curves are no longer effective at stimulating more economic growth or inflation].

A few important caveats are in order. When an economic recession is caused by a financial market failure, such as 2008‐2009, then central bank buying of assets (i.e., the Fed’s approach) or provision of emergency liquidity loans (i.e., the European Central Bank’s approach) can limit the damage of the recession and prevent a downward spiral into a depression. This ability to contain a recession, however, does not translate into an ability to promote additional economic growth when an economy is already growing again.

Moreover, the tendency of analysts and policy‐makers to embrace linear, or as some might call it — flat‐earth thinking — should be avoided. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) experimented with negative short‐term rates on the deposits of commercial banks held at these central banks. The idea was that if lowering rates from 4% to 2% could encourage inflation, and then from 2% to 0%, why not go negative? Unfortunately, economics is virtually never a linear relationship. As short‐term rates approached zero and then went negative, commercial banks saw their profits squeezed, as they could not pass on the negative rates to their depositors. Lower profits hurt lending, which was exactly the opposite of what the central bank was trying to do.

If Not Monetary Policy, What About Fiscal Policy?

After monetary policy failed to produce the additional economic growth and inflation pressure desired by policy makers, the US turned to fiscal policy. With legislation passed at the end of 2017, the US embarked on a rather grand experiment to see if a large permanent corporate tax cut could encourage economic growth and possibly push inflation a little higher. The long‐term outcome will be interesting to observe, and is not so clear, because the link between tax cuts and spending is quite loose. (See Chapter 3 for an in‐depth analysis of tax cuts and economic growth.) Corporations may choose to buy back shares, pay larger dividends, refinance debt, or make acquisitions – all of which have excellent potential to increase shareholder value and yet may have no impact on the real economy. Only if corporations use the tax cut to pay higher wages or to invest in expansion plans in the US will the domestic real economy see higher spending. Some of this may, indeed, happen. The big question is how much and will it be enough to make a material difference in the growth of the economy. If one assumes tax cuts unambiguously increase spending on goods and services, then higher real growth and inflation pressure follow from the assumption of higher spending demand. If one assumes the permanent tax cuts to corporations and the temporary rate cuts for relatively well‐off individuals will not raise spending demand by very much, then, of course, the impact on growth and inflation will also be small. [Note: Chapter 2 on “Taxes and Economic Growth” provides and in‐depth analysis of these issues.]

While not on the policy agenda in the US when the corporate tax cut was enacted, our analysis also suggests that increases in government spending is a more direct way to stimulate spending demand. After all, gross domestic product is the arithmetic sum of consumption, investment, and government expenditures, plus net exports. Raising government spending goes directly toward increasing spending demand in the domestic economy without any confusion or debate as there is with corporate tax cuts. Indeed, the restraint in the growth of US federal government spending during the 2010–2017 period – after the one‐time emergency fiscal spending of 2009 — was arguably one of the reasons that economic growth was not stronger even with near‐zero short‐term interest rates.

Another fiscal policy issue for analysis is the rise of the national debt. At least in the short‐term, both tax cuts and increased government spending would work to increase the deficit. Only if materially higher economic growth appeared down the road would tax revenues rise to partly offset the tax rate cuts or the increases in government expenditures. We carefully note, though, that rising debt loads do not signal future recessions. Over the long‐term, growing economies typically take on more debt relative to GDP. As the debt to GDP ratio grows, though, the economy becomes more fragile and more interest rate sensitive. That is, higher interest rates mean higher interest expense, and so rising national debt raises the risk of a monetary policy mistake – that is, moving too fast to a flat or inverted yield curve — and causing a recession. Our conclusion is that higher debt loads may well translate over the long‐term into a more cautious Fed in terms of raising short‐term interest rates.

And, Why Haven’t Tight Labor Markets Resulted in Rising Inflation?

Moving on to the labor market theories of inflation, the assumption labor economists, such as former Chair of the Federal Reserve Board Janet Yellen, typically make is that low unemployment rates are indicative of tight labor markets, meaning stiff competition for scarce labor and thus leading to higher hourly wages, which signals increased spending demand. There is, indeed, a loose contemporaneous correlation between wage inflation and consumer price inflation, but that relationship is not necessary causal — just an empirical association. And, as labor markets have shifted over the decades to more and more service sector jobs and less and less manufacturing jobs, the case for a causal relationship running from hourly wages to inflation was weakened if not destroyed.

To focus on spending demand, our preference is to look at the growth in total labor income. Total labor income growth is the sum of employment growth (more people working), growth in hourly hours worked (people working longer), and growth in hourly wages (people getting paid more). If you only look at any one of these items in isolation, you risk getting the wrong answer. In Janet Yellen’s defense, she strongly preferred a holistic approach to labor market data — looking at every measure possible to assess in a qualitative way what was really happening.

The focus many analysts put on hourly wage growth, though, is misguided. The problem is — yes, you guessed it — in the assumptions. The link between hourly wage growth and total labor income has a lot to do with what kind of jobs of being created, and most models that economists create assume that the job distribution within the economy is stable. Nothing, of course, could be more wrong in this era of corporate disruption. The economy is creating many more low‐paying service jobs and losing relatively better paid manufacturing jobs. This is a multi‐decade trend, so why so many academic and policy‐oriented economists do not give it more emphasis in their inflation forecasting models is a mystery to practitioner economists. The only relatively highly paid sector that saw job growth during 2010–2017 was business professionals, including those in finance, accounting, insurance, and legal professions, and this sector was too small to move the inflation needle. The basic point is that if the job mix is shifting to relatively lower paid professions, then the overall average hourly wage growth will be biased downward regardless of the path of consumer price inflation.

There is more to this story, too. Spending demand is a function of both ability and willingness to spend. The growth in total labor income measures the changes in the ability to spend, but it does not necessarily reflect the willingness to spend. Our view is that fear of losing one’s job is the primary factor affecting the willingness to spend.

After the 2008–2009 Great Recession, many companies shed jobs. If you kept your job, you may have witnessed family, friends, or co‐ workers lose their jobs. This is the province of behavioral finance and psychology. But we would argue that the recovery from a recession involves much more than job creation — the fear that swept through the labor force from the job losses in the recession may take much longer to diminish. Hence, spending demand undershoots a linear extrapolation of total labor income growth until the job‐loss fears abate. And, in this era of corporate disruptions, fears of losing one’s job have not abated very quickly. For example, brick‐and‐mortar retailing is being disrupted, and goods delivery jobs are being created. Overall, job growth is doing fine, unless you are in one of the disrupted sectors, and then fear of job loss remains. This means that in the long‐lasting yet modest economic expansion after the Great Recession of 2008–2009, spending d...