eBook - ePub

Marketing for Competitiveness: Asia to The World

In the Age of Digital Consumers

This is a test

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Marketing for Competitiveness: Asia to The World

In the Age of Digital Consumers

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Asia is the most populated geographical region, with 50% of the world's inhabitants living there. Coupled that with the impressive economic growth rates in many Asian countries, the region provides a very attractive and lucrative market for many busine

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Marketing for Competitiveness: Asia to The World by Philip Kotler, Hermawan Kartajaya;Den Huan Hooi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & International Marketing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

International MarketingIndex

Business

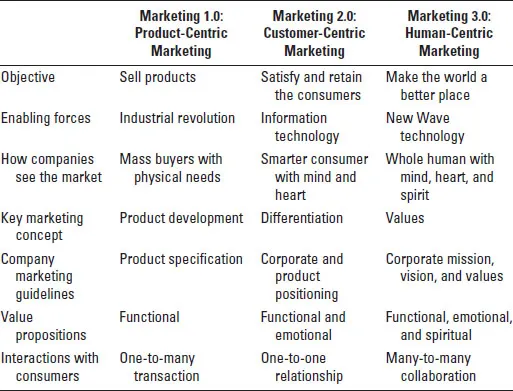

Over the past several decades, marketing has transformed through three stages that we call Marketing 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0. Long ago, during the industrial age — when the core technology was industrial machinery — marketing was about selling the factory’s output of products to all who would buy them. The products were fairly basic and were designed to serve a mass market. This was Marketing 1.0 or the product-centric era.

Marketing 2.0 evolved as a result of today’s information age — with information technology at the core of digital revolution. Consumers are now well-informed and can easily compare several similar product offerings. They can choose from a wide range of functional characteristics and alternatives. Today’s marketers try to touch the consumer’s mind and heart. Unfortunately, the consumer-centric approach implicitly assumes the view that consumers are passive targets of marketing campaigns. This forms the basis of Marketing 2.0 or the customer-centric era.

Now, we are witnessing the rise of Marketing 3.0 or the human-centric era. Instead of treating people simply as consumers, marketers are beginning to approach them as whole human beings with minds, hearts, and spirits. Increasingly, consumers are not only more aware about the many social and environmental concerns but also looking for solutions to their anxieties about making the globalized world a better place. They seek not only functional and emotional fulfillment but also human spirit fulfillment in the products and services they choose. Table A summarizes a comprehensive comparison of Marketings 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0.

Technology continues to play an important role but at the same time customers are becoming more human. Machine-to-machine (M2M) marketing tools are becoming more powerful if a company can utilize them to deliver human-to-human (H2H) interactions. In this transition and adaptation period in the digital economy, a new marketing approach is required to guide marketers in anticipating and leveraging on the disruptive technologies while maintaining the human-centric approach of Marketing 3.0. We call this approach Marketing 4.0.

Table A: Comparison of Marketings 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0.

Source: Kotler et al. (2010).

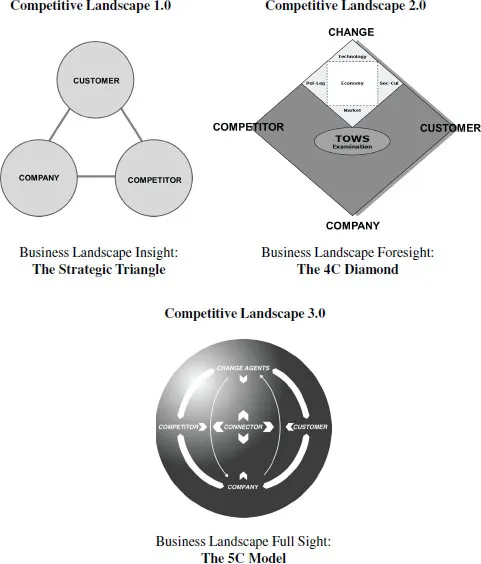

This marketing transformation — from products to customers to the human spirit — is also reflected in the different ways marketers are approaching, mapping, and analyzing the business landscape. We use three terms to illustrate the shift: (i) Insight (focus on current competitive landscape), (ii) Foresight (focus on future competitive landscape), and (iii) Full sight (focus on both current and future competitive landscapes and how all the factors are connected with each other) (see Fig. A).

Figure A: The dynamic arena.

Sources: Adapted from Ohmae (1982); Kotler et al. (2003); Kartajaya and Darwin (2010).

In the publication, The Mind of the Strategist, Ohmae (1982) introduced the three Cs of strategy (The Strategic Triangle). It is a business model that offers business landscape insights on the factors needed for success. It points out that a marketer should focus on three key factors for success. In the construction of a business strategy, three main players must be taken into account: Company, Customer, and Competitors (3Cs). In terms of these three key players, strategy is defined as the way in which a corporation endeavors to differentiate itself positively from its competitors, using its relative corporate strengths to better satisfy customer needs.

But our business landscape is getting more dynamic. The external forces of change — technology, economy, socioculture, political–legal, and market — cannot be neglected since they directly and indirectly affect company performance. Political–legal changes can result in the market becoming more open and competitive, and subsequently inviting more competitors to play in the existing arena. Sociocultural shifts, however, will not only alter how customers choose, but also they way they consume and dispose our products and services. In this dynamic landscape, we need to use the 4C Diamond model as our tool of analysis. The model consists of four interrelated factors: Change, Customer, Competitor, and Company. Change is value migrator, customer is value demander, competitor is value supplier, and finally company is value decider (Kotler et al., 2003).

In the New Wave era, all those factors are getting more connected. Changes in the external environment are easily tracked and monitored by all business players. Technology has provided us with so many practical tools to do so. Customers are also getting more access to information about our company as well as competitors. They can send requests, post questions, and even give complaints directly to companies without any physical and monetary barrier. A company and its competitors will need to compete to discover their customers’ anxieties and desires faster. Lack of agility and adaptability will divide business players into two general categories: first-mover and follower. Therefore, we need to put a fifth C to our competitive landscape analysis: Connector. Those who can connect better to external changes and customers will gain a competitive advantage against competitors. In a highly dynamic arena, connectivity will be the new winning formula (Kartajaya and Darwin, 2010).

More than 30 years ago, Kenichi Ohmae stated that a company can choose its strategy among three generic alternatives: corporate-based, customer-based, or competitor-based strategy. According to the previous explanation, we claim that there are three approaches in marketing: product centric, customer centric, and human centric. Despite the trend toward Marketing 3.0, some business players continue to adopt product- and customer-centric perspectives. That is something normal. But, to win the new digital consumers, the old perspective should be equipped with new technology. Chapters 4–6 discuss how different marketing perspectives can be applied successfully in the New Wave era.

References

Kartajaya, H and W Darwin (2010). Connect: Surfing New Wave Marketing. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

Kotler, P, H Kartajaya and I Setiawan (2010). Marketing 3.0: From Products to Customers to the Human Spirit. New Jersey: John Wiley.

Kotler, et al. (2003). Rethinking Marketing: Sustainable Market-ing Enterprise in Asia. Singapore: Prentice Hall.

Ohmae, K (1982). The Mind of the Strategist: The Art of Japanese Business. New York: McGraw-Hill.

CHAPTER 4

PRODUCT-CENTRIC PERSPECTIVE: CONNECTIVITY IN PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT

Information technology is revolutionizing products.

Smart, connected products have unleashed a new

era of competition.

Smart, connected products have unleashed a new

era of competition.

Michael Porter and James Heppelmann

Generally, in the early post–World War II years, a mass-marketing and “pure” product-centric strategy prevailed. Henry Ford was famous for his vision of the Model T as a standard product (offered in “any colour you want so long as it’s black”) and affordable to the broadest market. General Motors, under Alfred Sloan, offered “a car for every purse and purpose” (from Chevrolet to Cadillac) (Quelch and Jocz, 2008). Almost in the same era, Japanese manufacturers started building their industrial empires. Their strategy was based on a mass-market approach incorporating mass production, high volumes, and modest unit profit margins.

Only a limited number of manufacturers emerged from and flourished in Asia, resulting in a not-so-severe competition in the region — certainly not as tight as now. It was also because many countries in Asia had just implemented protectionist economic policies. Businesses in several countries were still monopolized by government- or state-owned companies (such as the Ministry of Transportation and Communications in Taiwan, Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited in Pakistan, and TELKOM in Indonesia) while regulations served to limit the role of the private sector in some specific industries. Not only the multinational companies, but also the local private companies did not have access to the free space and society as they have now. As a result, customers never really had many options to meet their needs.

In that era, businesses in the world — including Asia — were guided by the product concept suggesting that consumers favored those products that offered the best quality, performance, or innovative features. Managers in these organizations focused on making superior products and improving them over time, assuming that buyers could appreciate quality and performance. Product-centric companies often designed their products with little or no input from potential customers, trusting their engineers to design exceptional products. A General Motors executive once said: “How can the public know what kind of car they want until they see what is available?” (Kotler, 2001).

Centuries have since passed yet business strategy has continued to be driven by the ghost of the Industrial Revolution, long after the factories that used to be the primary sources of competitive advantage have been shuttered and off-shored. Companies are still organized around their products and production management, success is measured in terms of units moved, and organizational hopes are pinned on product pipelines. Production-related activities are honed to maximize throughput and managers who worship efficiency are promoted. Businesses know what it takes to make and move stuff. The problem is, so does everybody else (Dawar, 2013).

This “overconfidence” in a product-centric strategy can lead to marketing myopia (Levitt, 1960). Railroad management thought that travelers wanted trains rather than transportation and overlooked the growing competition from airlines, buses, trucks, and automobiles. Colleges, department stores, and post offices all assume that they are offering customers the right product and wonder why their sales slip. These organizations are too often looking into a mirror when they should be looking out of the window.

Gradually, the companies have begun to open up to feedback and criticisms from customers. Even as production processes and product innovations are still major sources of competitive advantage, customers have started to be on the company’s radar — everything from what they want to know to how to attract them comes under this. It is no longer just a pursuit of efficiency and productivity. Marketing or customer research has begun to find a place in business organizations, although product-centric companies still put more attention to and investments in product research and development (R&D).

In today’s competitive environment, only those companies that develop products that satisfy customer needs better than the products of their competitors will succeed. Therefore, it is necessary that companies conduct thorough research on such needs and generate ideas and solutions that can best satisfy them. The more innovative the new product development (NPD) projects, the greater the need to integrate marketing and R&D functions within the company. However, although the need for integration has been widely recognized, the levels of integration of R&D and marketing in practice vary across companies and industries. It is undeniable that until now there are companies that closely hold the principle that an innovative product will succeed in finding its place in the market. Apple cofounder Steve Jobs once said, “It isn’t the consumer’s job to know what they want”. That was Apple’s job.

Product Development and Connectivity

Decades ago, the secret of several Japanese corporations’ success was their skill in sequencing improvements in functional competence. In the 1950s and early 1960s, many of them made heavy investments in both money and talent in manufacturing, and together with the advantage in labor cost they enjoyed at that time, it constituted their principal source of strength. At this stage, their investments in R&D and overseas marketing were minor. In the 1980s, they started conducting basic research on improving their functional strengths (Ohmae, 1982).

Kenichi Ohmae, in The Mind of the Strategist, gave a classic example about this product-centric perspective. It was the case of Casio, a manufacturer of watches and pocket calculators, against its competitors. Most of its competitors are organized around the traditional functions of engineering, manufacturing and distribution, and have gone in heavily for vertical integration. Casio, in contrast, remained basically an engineering and assembly company with very little investments in production facilities and sales channels. Its strength is flexibility.

Recognizing its competitors’ inability to introduce new products rapidly, Casio had adopted a strategy of accelerating and shortening product life cycles. As soon as its 2-mm thick, card-size calculator was introduced to the market, Casio started rapidly bringing down the price, thus discouraging its competitors from following with similar products. Within a few months, Casio introduced another model, which emitted musical notes upon touching the numerical keys.

Casio’s internal strength was its ability to integrate design and development into marketing research so tha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Contents

- PREFACE THE ANATOMY OF CHANGE

- Part I MARKETING IS TRANSFORMING? Competitive Landscape: The Dynamic Arena

- Part II MARKETING IS MOVING? Competitive Position: The Core Essence

- Part III MARKETING IS CREATING? Competitive Marketing: The Whole Set

- POSTFACE GLORECALIZATION MINDSET Asia to the World!