![]()

Chapter 1

Foreword

This book is not a monograph by a professional historian. Rather it presents a collection of essays — some of them are written by myself, others by relatives of Genia Peierls (née Eugenia Kannegiser) or her friends. Compared to Western scholars, my opinions will inevitably differ for a number of reasons, which, perhaps, can be viewed as advantages. Firstly, I spent forty years of my life in the communist country, the (currently non-existent) Soviet Union. Living there certainly impacted my perspectives, so that I an able to assess issues which are not quite familiar to westerners. Secondly, Russian is my native language, which allowed me to investigate the youth years of Genia Peierls and the tragic fate of her parents. Thirdly, I am a professional theoretical physicist, rather than a historian of science, which may be viewed simultaneously as a strength and a weakness. I cannot be as systematic as historians usually are. However, because this is not a monograph by a professional historian, I had the freedom to focus on topics which interest me most.

I came to this book from a rather surprising direction. From my early university years I heard the famous “Landau stories.” Some of them refer to Landau’s Leningrad years. Genia Kannegiser was a prominent figure in these stories. I was always curious about what happened to her after her departure from the USSR in 1931.

My PhD thesis adviser, Professor Boris Ioffe, late in the evenings at the Institute,1 used to share with me some of his memories about his participation in the Soviet nuclear program. When he was a very young man he carried out some theoretical research on the hydrogen bomb.2 Needless to say, he knew all the key players: Zeldovich, Sakharov, Ginzburg, Landau, etc. His assessments of various events did not necessarily coincide with generally accepted views. This ignited my interest in the nuclear weapons programs in other countries, primarily Germany and the United States. As is well known, Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch (with their famous Memorandum [1]) were the driving force behind the inception of the Anglo-American program. The outcome of this program has shaped world history ever since. To a large extent it determined the lives of Genia and Rudolf Peierls.

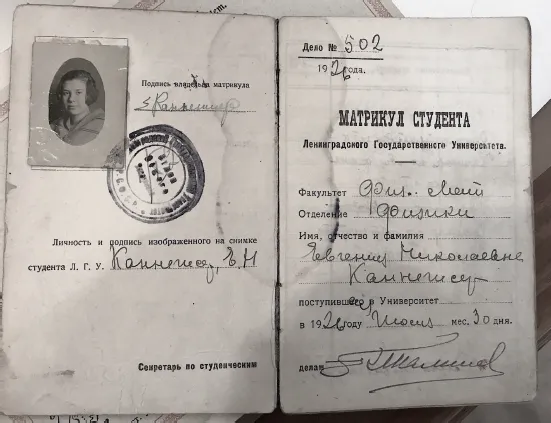

Figure 1.1 Genia Kannegiser’s student identification and record book. Personal data are on pages 1 and 2, subsequent pages (e.g. page 51) present her progress in academic disciplines over the years. On the left side of the student book you see Genia’s photo, her Russian signature and the university seal. The right-hand side reads:

File 502, 1926, MATRIKUL of the Leningrad University student. Faculty of Physics and Mathematics, Department of Physics. Evgeniya Nikolaevna Kannegiser entered the University in 1926, July 30.

*****

This book might have had more than one beginning, but I will start from a remarkable love story that lasted for over half a century. Love, friendship, and physics intertwined together.

The year of 1930 did not seem particularly alarming.

Of course, in hindsight symptoms of the approaching disasters were evident. The National Socialist Workers Party of Germany — Hitler’s party — won 107 seats in Germany’s parliament (18.3% of all the votes), making them Germany’s second largest party after the Social Democrats (with 24.5% of all votes). In three years Hitler would become the Chancellor of the Third Reich. The crash of the New York Stock Exchange on September 29, 1929, was a harbinger (and a trigger) of the full blown Great Depression which swept across the world two to three years later. In Russia, the relatively liberal years of New Economic Policy3 came to an end in 1928. In 1930, Stalin ordered accelerated forced collectivization: all peasant households were united in kolkhozes against the will of the owners. Millions of the wealthiest peasants (the so called kulaks) were sent in exile to Siberia. Just two years later, this would result in Holodomor, an artificial famine in Ukraine and other parts of the country in which millions died of starvation.

In physics, 1930 was a quiet year too. The breakthrough discoveries of fundamental quantum laws were earlier in the past while most of the breakthrough applications would shake the world a few years later. Arguably, the most important theoretical development of the year due to Heisenberg and Pauli [2] referred to the nascent quantum field theory. They showed that material particles could be understood as the quanta of various fields, in just the same way that the photon is the quantum of the electromagnetic field. Looking through the summer issues of Physical Review I came across a single paper which attracted my attention — that by Gregory Breit [3]. It was devoted to spin interaction of electrons. Nuclear Physics was in its infancy in 1930.

For the main characters of this book — Eugenia (Genia) Kannegiser and Rudolf Peierls — the summer of 1930 was fateful. In August 1930 they met for the first time in Odessa (currently, a Black Sea port in Ukraine), and spent about two weeks together which shaped their destinies.

As their daughters Gaby and Joanna told me, it is hard to imagine more contrasting people. Rudolf was quiet and reserved, while Genia was exuberant, straightforward and outgoing. This will become evident from their letters below. In a conversation I had with Gaby Gross (née Peierls) on August 17, 2017, she told me:

You know, at a certain point in my life a thought crossed my mind that Genia married Rudolf just to get out of the USSR. But then I read the letters and understood that it was a pure and true love, of the type that rarely happens. But it happened.

The conference at which they met brought together almost all actively working Soviet scientists and a number of foreign guests, Wolfgang Pauli and Rudolf Peierls, among others. At that time 23-year old Peierls was Pauli’s assistant. Genia had graduated from the Department of Mathematics and Physics of Leningrad University in 1930 and worked at Leningrad Geophysical Laboratory. She was 22 years old and went to the conference at her own expense out of interest. Genia Kannegiser’s family had ties with Odessa from time immemorial, as we will see in Chapter 5.

Figure 1.2 Odessa Opera, 1930s.

The above statement that Genia graduated from Leningrad University should be understood in the context of Soviet realities of that time. In 1969, in an interview conducted by Charles Weiner for the American Institute of Physics Oral History project, Rudolf Peierls explained [4]:

Genia had essentially got what we’d call a bachelor’s degree, except she hadn’t got a degree because of her background [from a bourgeois family]. Her training was that of a first degree in physics, and she then worked as what we’d call a research assistant, a technician. I mean she was taking readings at one time on some nuclear physics and at other periods in some geophysical work.

Apparently, in no time a spark connected the hearts of the young people. They spoke in English as this was the only language they had in common. They talked for two weeks or so, and then Rudolf returned to Zürich and Genia to Leningrad. They made arrangements to meet again in March 1931. That’s how the romance encompassing exotic locations and love that overcame obstacles started. Rudolf Peierls’ book [5] gives a sketch of this story:

The boat took us to Batumi, and this was my first experience in a subtropical climate with unfamiliar vegetation, at its best in the beautiful botanical gardens, some way out of town, which we visited. But coming back, we had a little adventure. We were just in time to catch the train that was to take us back into town, but there was a long queue at the ticket office, and it was obvious that we would miss the train. I mentioned that at home we would just get on without a ticket and pay on the train, and our Russian friends said, “Let’s try that!” But the conductor on the train was not amused. He called the armed guards that accompanied the train. Two soldiers stood over us with fixed bayonets, and in Batumi they marched us to the station master’s office. After difficult negotiations it was ruled that the Soviet citizens in the party would have to pay a fine; the foreign visitors, who could not be expected to know the rules, were let off. Needless to say, the fine was shared.

We went on by train to Tbilisi (Tiflis)4 with a diminishing group. It was an old town, beautifully situated among mountains. The Georgian people were not as wild as they looked, with the men’s enormous handlebar mustaches and traditional costumes. One heard many tales about the wild temperament and the drinking habits of the Georgians, but our stay was too short to witness any of it.

An even smaller group, but still including my new friend Genia, continued in a hired car to Vladikavkaz beyond the mountains, where there is a railway to the north. Here the group dispersed; Genia and I decided to visit Kislovodsk, a resort in the high mountains. This involved another overnight journey by train. I was anxious to see how the locals travel and wanted to go by the “hard” class, where seats are not reserved. So Genia and I got into a crowded carriage full of wild-looking local types. Genia squeezed into a seat between them. There was no seat left for me, but I spotted some empty space on the wooden luggage rack. I climbed up and tied myself down with my belt so that I would not fall off while asleep. I slept so soundly that Genia had to shake me when we reached our destination. The stay in the mountains passed only too quickly, and when Genia and I parted I left with the feeling that something new and permanent had entered my life.

After Genia and Rudi parted, they started corresponding almost on a daily basis. Six months separated their first encounter in Odessa from their wedding in Leningrad on March 15, 1931. It was another six months or so before the exit visa from the USSR was issued to Genia. Miraculously, 67 letters exchanged between Genia and Rudi in that year survived. Some of them are collected in Chapter 4. After Rudi’s return to Zurich in September 1930, he started studying Russian. It was remarkable that in three months, on November 30, he wrote his first letter to Genia in Russian! Moreover, when Peierls went to Leningrad in March 1931 he was asked to deliver a course of lectures on quantum theory of condensed matter in Russian, and he proved to be up to the task.

At the end of April it was time for Rudi to leave Leningrad and join Pauli in Zurich. He returned to Leningrad on August 15 in anticipation of the approval of Genia’s petition to leave the USSR. In fact, it was not ready until weeks later. Six weeks of adventures in the Caucasus mountains and misadventures with the exit documents followed. Genia’s visa materialized literally in the last minute. The Peierlses were finally able to leave for Zurich in late September.

They were incredibly lucky, Rudi and Genia. If they happened to meet two or three years later under the same circumstances, it is highly unlikely that the above events could have happened. From Stalin’s ascent to absolute power till the collapse of the Soviet Union, mere contact between Soviet citizens and foreigners was strictly controlled, let alone emigration.5 This control was established shortly after the Bolshevik coup d’état in 1917.

The rules, introduced on June 1, 1922, for traveling abroad required a special permit from the People’s Commissariat of Foreign Affairs (NKID). This made the process highly restrictive, eventually transforming it into a complete ban by 1934–35.

In Regulations on Entry and Departure from the USSR published on June 5, 1925, all foreign countries were declared “hostile capitalist environment.” In addition to previous constraints, one extra was added — permission from the GPU.6

Two examples of the forced isolation of Soviet science (imposed by Stalin) are widely known in the world physics community. They will be mentioned in Chapter 14.

In 1933, George Gamow was invited to give a talk at the Solvay Conference in Brussels. The exit visa was issued to him, but not to his wife Lyubov Vokhmintseva (whom he called Rho). It was the interference of Nikolai Bukharin, a high-ranking government official,7 that hel...