![]()

C H A P T E R | 1 |

| Migration and Social Diversity in Singapore1 |

| BRENDA S A YEOH |

INTRODUCTION

Singapore as a small, natural resource-scarce city-state has been part of global enterprise and global service capitalism since its very birth. As a child of imperial and labour diasporas in the colonial era, our story is very much intertwined with migration and migrants. An openness to migrants is how we have gained importance and stature in the world. With the colonial era behind us, we are a “wannabe” global city, competing very hard for a place in the top league of globalising nations. Once again we are a convergence node for transnational flows of different sorts of migrants from many parts of the world.

A migrant history is thus where we come from and that gives us, hopefully, a sense of empathy for migrants. We know the inside story of migration because it is part and parcel of our being, our histories, our families perhaps, and our place in Singapore today. And as part of the story of migration, a dependence on foreign labour is also very much part and parcel of our economic survival through the times, from the colonial era right up to today.

Our economy today is restructuring and transiting to services, financial and high-technology areas. Migrant labour continues to be crucial. The Ministry of Manpower puts it in a nutshell when it says in the Manpower 21 statement that the employment of foreign manpower is a “deliberate strategy to enable us to grow beyond what our indigenous resources can produce”. In Singapore, a city-state that is very well managed in many regards, leveraging on migrant labour is part of this carefully managed, “deliberate strategy” of growth.

CHANGING POPULATION COMPOSITION

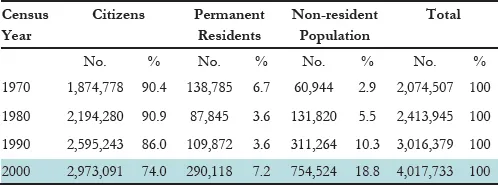

So what implications do the increased flows of migrants have on the social landscape of Singapore? Let us first take a look at Table 1 which shows population figures compiled from census reports.

Table 1 Changing proportion of citizens to non-citizens in Singapore

SOURCE Adapted from Yeoh, 2006, page 28, Table 1.

As of the year 2000, the non-resident population makes up 18.8 per cent of a population of just over four million, in other words, one in five people on this island. If we focus on the division between citizens and non-citizens instead, then basically every one in four people on the streets that we meet today is a non-Singaporean.

Turning now to changes over the decades, it is obvious that the non-resident population is the part of the population that is growing in the most rapid fashion, almost doubling every decade in terms of its percentage of the total population. In short, from the 1970 census to the 2000 census, the population of Singapore has doubled from about two million to four million. The non-resident population has grown from 2.9 per cent in 1970 to a hefty 18.8 per cent of the population of four million today. The non-citizen population has likewise grown from 9.6 per cent in 1970 to 26 per cent in 2000. The 2005 figures also show a further increase of the non-citizen population to 28.4 per cent out of a total population of 4.3 million.

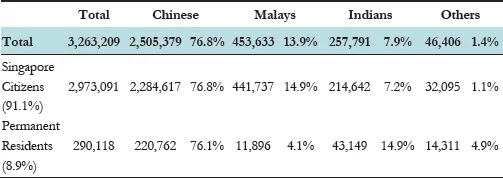

Table 2 Resident population by ethnic group and residential status

SOURCE Department of Statistics, 2000.

In terms of ethnic composition, the CMIO (Chinese, Malays, Indians and Others) model that is foundational to Singapore’s multi-ethnic philosophy remains more or less in place despite the decades of inmigration. However, there are dips in the Chinese and Malay percentages and increases in the Indian and Others percentages. This may be accounted for if we look at the differences in the ethnic profile between Singapore citizens and Permanent Residents (see Table 2). Among the Permanent Residents, the Indian population is 14.9 per cent, which is twice the percentage of Indians within the Singapore citizen pool. The Others category, of course, features as a larger percentage of the Permanent Resident population than of the Singapore citizenry.

“NEW” SOURCES OF SOCIAL DIVERSITY

Clearly, then, we have been an immigrant society of considerable diversity since our beginnings as a port-city. Today, under conditions of globalisation, what sorts of new social diversity do we confront? As Singapore fashions itself as a magnet for foreign manpower, we have in our midst different categories of migrant labour. “Foreign workers” is the term we tend to use to refer to the large numbers of low-skilled labourers in construction, manual work, cleaning and domestic work. A category that is much smaller in number but of importance is skilled labour — employees at the professional and managerial level, whom we commonly refer to as “foreign talent”. A third group that is increasingly important — because they are the future manpower — and growing in numbers is the foreign students. At all levels there has been an increase in foreign students in our schools and institutions of higher learning. In sum, the non-resident workforce of over 600,000 in 2000 makes up about 30 per cent of total employment in Singapore, the highest figure in Asia.

Managing “Foreign Workers”

We first turn to the category of foreign labour that has the largest number. Foreign workers, who number more than half a million in the industries mentioned before, come from a wide range of countries and include Chinese, Indians, Filipinos, Thais, Malaysians, Indonesians, and Sri Lankans. These workers perform the kinds of work that Singaporeans themselves have been reluctant to do.

Our changing social landscape shows signs of their presence. We see them in Little India, the Golden Mile Complex, Orchard Road, and other public places when they leave the confines of construction sites, workers’ dormitories and employers’ homes on their days off.

On 3 March 2002, a photograph which appeared in The Straits Times showed a scene rarely seen in Singapore. A group of Chinese nationals working in the construction industry had staged a protest outside Parliament House to remonstrate against what they felt was the slow pace of investigations into the case of a remittance agent who fleeced them of large sums of money. Riot police had to be deployed to break up the protest — certainly something of a head-turner in Singapore, for how many Singaporeans would stage a protest outside Parliament House to demand justice? This is perhaps a sign that things are changing, not just in the economic sphere, but also in the socio-political sphere.

Socio-political change is, however, also kept carefully in check. Foreign workers are “managed” through a whole series of control measures — including the Work Permit system, the dependency ceiling, government levies and the security bond — to ensure that they remain a transient population, carefully regulated in order to avoid what may seem to be disruptive social effects. State policy is opposed to the long-term immigration of low-skilled workers and is directed at ensuring that they remain temporary and easily repatriated in times of recession. As part of this overall policy of transience, family formation is circumscribed, dependents are barred, and marriage to Singaporeans or Singapore Permanent Residents is not allowed. And for the women — that is, foreign domestic workers — getting pregnant amounts to repatriation. In short, state policy treats foreign workers as disposable labour which must not remain threaded into the basic fabric of Singapore society.

Attracting “Foreign Talent”

Cities which are seriously competing in the globalising game are very much concerned with what has been called a “global war for talent”. Singapore is no exception and there is an all-out effort to build Singapore into a “brains service node”, an “oasis of talent”, or the “Talent Capital of the New Economy”, to use some of the catchphrases contained in government documents and speeches. While foreign talent comes from a wide spectrum of countries, numbers from China and India in particular have been growing rapidly in the last decade or so.

Major initiatives have been launched to attract, retain and absorb foreign talent, such as the liberalisation of immigration policies, recruitment missions, Permanent Residency schemes and company grant schemes which ease the cost of employing skilled labour. The whole re-imaging of the architectural and cultural frameworks of urban development is yet another major initiative that serves the purpose of attracting and retaining talent. Efforts to remake Singapore into a “Global City for the Arts” are at least partly aimed at retaining foreign talent who might not want to stay on if Singapore remains a cultural desert.

Skilled individuals in arenas ranging from science and technology to sports — including their family members and dependents — are hence part and parcel of our everyday social landscape. Living in a globalising city means that we encounter these individuals regularly beyond the workplace, on the streets, in shopping centres, schools and so on.

Investing in “Foreign Students”

Another source of social diversity takes the form of international students as Singapore seeks to fashion itself as an education hub for the region. The “Global Schoolhouse” project, as it is called, involves creating Singapore as a world class educational hub, known for its intellectual capital and creative energies. Investing in foreign students is another way of augmenting our pool of skilled manpower for the near future. This is a strategy that affects the whole education landscape from schools to universities. Here, Singapore is capitalising on its various strengths, including its English-speaking environment, high standards of education, low crime rates, high order of social discipline, as well as what has been called our “squeaky clean”, “nanny state” reputation, to make parents feel assured about sending their children here.

The aim is to more than double the number of foreign students coming to our schools and universities from about 66,000 in 2005 to 150,000 by 2012. The main targets are China and India as well as neighbouring Southeast Asian countries.

Turning to “Foreign Spouses”

Social diversity in Singapore is not just a product of the nation’s labour policy. While manpower needs are the main drivers for the increasing social diversity we are experiencing in the population, there are other pressures at work. One of these has to do with the falling marriage rates in Singapore.

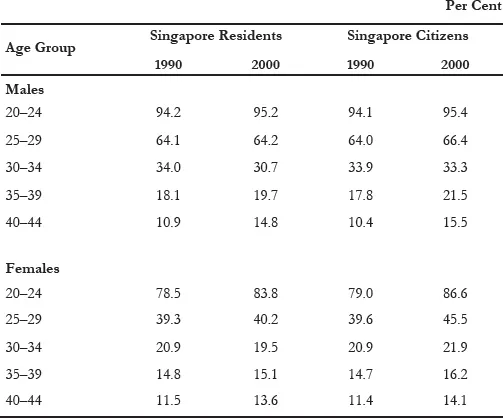

As seen in Table 3, the proportion of singles has gone up over the decade (1990–2000) in nearly all age groups among both Singapore citizens and residents. The increase in the rate of non-marriage as well as delayed marriage has been the subject of much public discussion as well as the source of state anxiety in recent years. Various reasons have been propounded, including the hectic pace of life in a globalising city that squeezes out time for love, sex and marriage, as well as the higher levels of education, financial independence and career-mindedness among Singaporean women. Social perceptions of singlehood are apparently also changing, becoming more acceptable than before.

Table 3 Proportion single by residential status, sex and age group

SOURCE Singapore Department of Statistics, 2000.

Linked to these trends, Singaporeans searching for suitable marriage partners are increasingly turning to sources from abroad. As with globalising cities elsewhere, for example, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea, turning to “foreign brides” from the region appears to be a growing trend in Singapore. Foreign spouses are hence an important source of social diversity that affects the basic social fabric of Singapore.

According to the Department of Statistics, there were 8,116 marriages (35.3 per cent) between residents and non-residents in 2005. This can be broken down into 6,520 male Singaporeans and Permanent Residents wedded to foreign brides and 1,596 of their female counterparts marrying foreign grooms. As the actual nationalities involved in these cross-nationality marriages are not released to the public, one can only speculate that the foreign brides are largely Chinese, Indian or Southeast Asian, perhaps, Vietnamese, Filipinos and so forth. Looking at the websites of matchmaking agencies, it appears that marriages to foreigners can be facilitated by packaged tours to Vietnam, for instance, to handpick one’s partner from a wide range of applicants.

CURRENT DEBATES — MIGRATION AND INCREASING SOCIAL DIVERSITY IN GLOBALISING SINGAPORE

Migration, and the increasing social diversity it brings, have been very much in the news in recent years. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong gave these issues a central place in his 2006 National Day Rally, emphasising a three-pronged approach: encouraging procreation among citizens, engaging overseas Singaporeans in order to help them fit in when they return, and attracting foreigners who can contribute to Singapore to work, live and settle in the city-state. Apparently, efforts to recruit and retain foreigners and convert them to Singaporeans are bearing fruit because in 2005, there were 12,900 new citizens, compared to the usual 6,000 to 7,000 new citizens in the last four years before 2005. This gain seems substantial compared to the average figure of 800 Singaporeans giving up their citizenship each year.

SINGAPORE AS PERMANENT MAGNET FOR TALENT OR TRANSNATIONAL REVOLVING DOOR?

A key issue I would like to raise for discussion relates to the question of the permanence of the foreign population within our workforce. There is, of course, a major differentiation between the unskilled workers and elite transnational workers. For the unskilled workers, the revolving door is one that turns systematically and continually. “Use and discard” is the underlying philosophy behind a range of policies such as the Work Permit system which have been put in place to prevent unskilled workers from gaining a foothold in Singapore as socio-political subjects. Basically, we extract their labour for a certain number of years and then we send them back to their home countries.

In contrast, among the elites with talent and skills, the state tries to slow down this revolving door as much as possible and in fact encourages them to put down roots in Singapore, if not by becoming citizens, then as Permanent Residents, or at least as individuals willing to work in and contribute to Singapore for a good number of years.

Studies, however, seem to indicate that international talent is highly mobile. Even when Permanent Residency status and Singapore citizenship are used as carrots, they will not necessarily guarantee the integration of talented individuals into the fabric of Singapore society. In fact, attaining Singapore citizenship or Permanent ...