![]() Section Two

Section Two

Substantive Topics and

Key Issues![]()

Chapter 8

Traditional Medicine and Traditional Birth Attendant Use During Pregnancy and Birthing in Low to Middle-Income Countries

Bradley Leech, Jon Adams and Amie Steel

Introduction

Traditional medicine (TM) is increasingly being used among women during pregnancy and birthing throughout low to middle-income countries (LMICs). Rural and remote regions of LMICs have limited access to health services including skilled birth attendants (SBAs). Many of these rural and remote regions rely on traditional birth attendants (TBAs) to support expectant mothers through pregnancy and birthing. TBAs are trusted and valued members of the community who are frequently the source of information about TM use during pregnancy and childbirth. This chapter will provide an overview of pregnancy and childbirth in LMICs, illustrating many of the obstacles women encounter during pregnancy then it will describe the role TBAs play with a focus on TM use. Lastly a research agenda is discussed situating the current level of knowledge and illustrating gaps in the research.

Pregnancy and Childbirth in Low to Middle-Income Countries

In contemporary LMICs pregnancy and childbirth remain a life-threatening event for many woman and newborns. In contrast to highincome countries, the journey of pregnancy and birthing in LMICs is characterized by a wide range of possible complication and even death, many of which are preventable (MacDonald, 2017). Such complications and challenges are exacerbated by the limited number of health care professionals available to many local communities — for example in the Machakos District of Kenya the doctor-patient ration is reported to be 1:62,325 (Kaingu et al., 2011). As a result, a large percentage of births in LMICs occur outside of health facilities and are related to an increased risk of mortality and morbidity (Bukar and Jauro, 2013).

While there has been a 3.3% decline in maternal mortality from 2005 to 2013 throughout 109 LMICs (Verguet et al., 2014), an estimated 153 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births still occur (Bauserman et al., 2015). There are many factors increasing the risk of maternal death in LMICs including a lower education level, a lack of antenatal care, experiencing a caesarean section delivery, experiencing haemorrhaging and the woman having hypertensive disorders (Bauserman et al., 2015). In fact, both haemorrhaging and hypertensive disorders contribute to one-third of maternal deaths in LMICs with ruptured uterus and sepsis being the most lethal obstetric complications (Bailey et al., 2017). Most complications in LMICS occur during delivery with some countries such as Morocco experiencing morbidity rates as high as 38.1% (Elkhoudri et al., 2016).

Globally, 99% of the 4 million neonatal deaths that occur yearly, happen in LMICs with the direct causes being an infection (mainly pneumonia and diarrhoea) (36%), preterm birth (28%) and asphyxia (23%) (Lawn et al., 2005). A large percentage of neonate deaths occur >37 weeks gestation with the majority occurring within 24 hours of delivery (Belizan et al., 2012). The 2017 Levels and Trends in Child Mortality annual report (Hug et al., 2017) highlighted many key areas in child survival in LMICs. Firstly, there has been a sharp decline in the under-five mortality rate from 93 deaths per 1000 live births in 1990 to 41 deaths per 1000 live births in 2016 (a 56% decline over this period). However, this remains high compared to 5.3 deaths per 1,000 live births in high-income countries. Approximately 7000 babies in LMICs died in the first 28 days of life every day during 2016. Newborn death rates are highest in Southern Asia (39%) and sub-Saharan Africa (38%) with the five countries accounting for half of all newborn deaths being India (24%), Pakistan (10%), Nigeria (9%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (4%) and Ethiopia (3%) accounting for half of all newborn deaths worldwide. It has been estimated that if trends continue in the 50 countries which fail to meet the Sustainable Development Goal of child survival, almost 60 million children under the age of 5, especially newborns, will die between 2017 and 2030 (Hug et al., 2017).

What do We Know About Traditional Medicine Use During Pregnancy and Birthing?

The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that 80% of individuals residing in rural areas of LMICs use TM for health needs, including during pregnancy and birthing (World Health Organization, 2002). Herbal medicine is the most frequently used TM in LMICs by women during pregnancy with an estimated prevalence range of 20–79.9% (Shewamene et al., 2017). This prevalence is suggested to be lowest in urban areas where SBAs are more accessible and highest in rural areas as access to health care is limited. The largest portion of women who use TM are low-income earners with no formal education (Shewamene et al., 2017). These women source information on TM from mainly TBAs followed by traditional healers and elderly women within the community (Shewamene et al., 2017).

Traditional Birth Attendants

TBAs have long been an essential part of pregnancy and birthing throughout LMICs as they are a major support network for expectant mothers throughout gestation. TBAs are viewed as a trusted and valued member of the community who are generally elderly women that have personally experienced childbirth and support mothers with home deliveries. Typically TBAs have no forming training in midwifery and acquire their knowledge through family members who were previous TBAs, allowing knowledge to be passed down through generations. TBAs are independent of the health care system, receiving no financial or medical support from the government (World Health Organization, 2004). However, in some instances TBAs may receive basic training to help identify mothers and newborns ‘at risk’ of complications and they are encouraged to refer at risk mothers and newborns to the nearest health facility if accessible (World Health Organization, 2004).

TBAs are valuable and accessible members of the community providing physical and psychological care pre-, intra- and postpartum (Byrne et al., 2016). Many women in LMICs perceive TBAs as the primary person responsible for supporting them throughout their pregnancy (Ngunyulu et al., 2015). In many rural and remote regions, TBAs are the exclusive care option for expectant mothers due to the distance to the nearest birthing facility. It has been suggested that more than half of home deliveries in LMICs are attended by TBAs (Bukar and Jauro, 2013).

TBAs and community elders have been found to use upwards of 35 medical plants for supporting pregnant women with some reports suggesting use of up to 55 different medical plants in their management of pregnancy complications (Alade et al., 2018; Kaingu et al., 2011). Such herbs are prescribed by TBAs for use throughout gestation with most herbal medicines recommended during delivering to avoid complications (Lech and Mngadi, 2005). TBAs have also been identified as advising women with regard to other related issues. For instance, TBAs will sometimes advise on delivery position (with squatting being the preferred position promoted by TBAs) (Lech and Mngadi, 2005). TBAs use a variety of techniques to remove placenta if retained such as abdomen/uterus massage (23.4–47%), manual extraction (15–24.6%), and advising the mother to blow an empty bottle (18.2%) (Bucher et al., 2016; Lech and Mngadi, 2005). TBAs also advise women on dietary and nutritional recommendations for foetus growth, energy during labour and postpartum food intake (Byrne et al., 2016).

TBAs appear to treat many common ailments associated with pregnancy (Alade et al., 2018). However, they have also been found to lack basic hygiene practices resulting in increased risk of infectious disease. This is of significant concern as infectious diseases are the single greatest direct cause of neonatal deaths in LMICs (Lawn et al., 2005). Another area where TBAs appear to use inappropriate or outdated practices is with regard to obstetric complications and newborn care (Bucher et al., 2016). These practices vary demanding on many geographical and cultural attributes with one study reporting 34% of TBAs as employing some form of potentially harmful product such as cow dung, red ochre, soil or ash to cover the cord stump (Lech and Mngadi, 2005).

Skilled birth attendants (SBAs) are qualified as either a midwife, nurse, or doctor and are able to manage all areas of pregnancy and childbirth (Munabi-Babigumira et al., 2017). In some LMICs such as Kenya, there has been a rise in the number of births attended by an SBA in recent years (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics — KNBS et al., 2010, 2015). Although SBAs are qualified in many areas relating to childbirth they still encounter many challenges affecting their ability to provide optimal patient care (Munabi-Babigumira et al., 2017). A major challenge is convincing expecting mothers to deliver at the health facility rather than having a home birth (Byrne et al., 2016). SBAs often perceive the strength of TBAs to be emotional support for mothers and an asset to the community and health care system (Byrne et al., 2016).

It has recently been proposed that the role of TBAs requires redefinition in response to an increasing number of modern health facilities becoming available, especially in developing regions. One study suggests that TBAs may be a vital aspect of supporting facility-based delivery by referring or accommodating women in labour to attend a health facility (Pyone et al., 2014). The collaboration of care by TBAs and SBAs is a viable proposition for LMICs (Byrne et al., 2016). While TBAs support and encourage mothers to visit a health facility for immunization and postnatal care (Lech and Mngadi, 2005), there remains controversy surrounding when TBAs should refer expecting mothers to seek assistance via a health facility (Bucher et al., 2016).

The WHO has supported and encouraged the integration of TBAs into the health care system over the last two decades (Stanton, 2008). However, many challenges have been identified and are required to be addressed for optimal patient care (Wilunda et al., 2017). Integrative care between TBAs and the health care system has been implemented in Timor-Leste, with a high degree of success (Ribeiro, 2014). In particular, since incorporating TBAs into the national health care system a reduction of maternal mortality has been observed from 660 per 100,000 live births in 2003 to 557 per 100,000 live births in 2010. Such integrative care has also seen an increase in referrals by TBAs to SBAs and has also increased the access to health care in rural communities (Ribeiro, 2014).

Determinants of Traditional Medicine Use in Pregnancy and Birthing

Women in LMICs have a cultural trust towards TM given the long history of use, accessibility and affordability. Many women in LMICs perceive TM as more effective than Western medicine in treating complications and ailments associated with pregnancy (Shewamene et al., 2017) and women are more inclined to use TM compared to Western medicine due to cost considerations (Shewamene et al., 2017). It has been suggested that a major factor determining women’s TM use in LMICs is related to limited access to Western medicine (Shewamene et al., 2017). Traditional healers and TBAs are usually accessible in rural areas where Western medical facilities are not. Furthermore, some TM such as herbal medicine can be grown in the community and is often gathered from the bush or sourced from traditional healers (Nyeko et al., 2016).

Reasons for TM Use During Pregnancy and Birthing

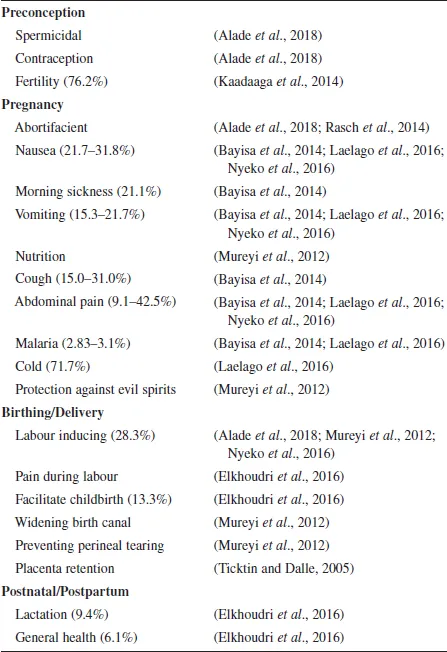

TM is used throughout pregnancy from preconception and contraception to inducing labour and postnatal care (Table 1). The majority of the TM used by women is to: treat common ailments associated with pregnancy such as nausea, morning sickness and abdominal pain; assist with labour; and prevent perineal tearing, prolonged labour and placental retention. TM use in some parts of sub-Saharan Africa incorporates religion and the belief in God, with TM, used to ‘protect against evil spirits’ during pregnancy (Mureyi et al., 2012).

Table 1. Action of traditional medicine use.

TM Used During Pregnancy and Birthing

A recent systematic review has examined the use of TM for maternal and reproductive health complaints as well as for well-being among African women (Shewamene et al., 2017). The herbal medicine frequently used by these women includes ginger, garlic, aniseed, fenugreek, green tea, eucalyptus, peppermint rue, madder, garden cress, cinnamon, bitter leaf, neem leaves, palm kernel, bitter kola and jute leaves. These herbal medicine ingredients are prepared and administered in various ways. The most popular methods to prepare herbs for the use during pregnancy is crude/ whole plant (43.2%) and infusion/extract (23.2–42.3%) followed by maceration (19.2–23.2%), decoction (10.5–17.3%) and powder/crushed (19.2%) (Alade et al., 2018; Bayisa et al., 2014; Elkhoudri et al., 2016). Typically these preparations are taken orally (22–84.9%), applied topically (10.1%) or applied intra-vaginally (13.0–33.0%) (Alade et al., 2018; Laelago et al., 2016; Rasch et al., 2014). Many of the TMs used for pregnancy and birthing in LMICs, especially herbal medicine, are reported in the literature for their use in pregnancy and also other conditions not related to pregnancy or birthing (Alade et al., 2018).

TM incorporates a large number of internal, physical and psychological therapies. The main TM therapy used by women during pregnancy in LMICs is herbal medicine. However, other TM used during pregnancy and birthing have limited research exploring their application and especially their effectiveness (Mureyi et al., 2012). Preliminary evidence indicates that practices used by women during pregnancy and birthing in LMICs vary from the conventionally accepted method such as manual exercise, steam baths and castor oil to unorthodox treatments including elephant dung and soil from a burrowing mole (Mureyi et al., 2012).

TM Use During Pregnancy and Birthing: A Summary

Herbal medicine remains the most widely used TM category during pregnancy and birthing in LMICs (Shewamene et al., 2017). A substantial proportion of such herbal medicine use is employed throughout pregnancy especially during delivery to avoid complications (Lech and Mngadi, 2005). TBAs have long been an essential part of pregnancy and birthing in LMICs with women viewing TBAs as tru...