![]()

PART 1

History

Systemic risk and systemic crises have a long history, reaching (at least) as far back as the Tulip Mania in the 17th century.1 This part presents cases of systemic bank crises, their trigger events, and their impact. We aim at understanding the different aspects of systemic risk and systemic crises.

Over the past 40 years, systemic risk has come to the forefront of regulatory and public attention. The increased importance of systemic risk is partly rooted in fundamental changes in the way banks operate now. Technological and financial innovations have changed their operations substantially; financial innovation in the form of securitization and derivatives trading have allowed new forms of sharing risks; and globalization has affected businesses and banks alike.

Over time, our understanding of systemic risk has changed. At the end of the 20th century, systemic risk was commonly addressed nationally and in the context of counterparty risk. It was often modeled via interbank linkages and/or allocation imbalances (see, e.g., Kaufman, 1995; Kaufman and Scott, 2003). The financial crisis of 2008, and most specifically the default of Lehman Brothers, has altered this perception fundamentally. Instead of modeling systemic risk itself, researchers now analyze how systemic risk spreads throughout the banking system and how minor events serve as amplifying factors. Thus, the focus has turned to the outcomes of systemic risk and the propagation and amplification effects.

Before the 21st century, systemic risk was mostly a national concern; but with the new century, systemic events reached the global level. Therefore, we split our historic overview in two parts. The first Chapter focuses on events at the end of the 20th century and highlights the systemic risk events in individual countries across the globe. The second Chapter then discusses global systemic events in the early 21st century. After this overview of historical systemic events, the third Chapter summarizes the main aspects and mechanisms of systemic risk.

1The Tulip Mania is a period in the Dutch Golden Age during which contract prices for bulbs of fashionable tulips reached extraordinarily high levels and then dramatically collapsed in February 1637. See Reinhart and Rogoff (2009), Bordo et al. (1995), Bordo (1990) and Brunnermeier and Schnabel (2015), among others, for additional information on historical (systemic) bank crises.

![]()

Chapter 1

Major systemic crises across continents at the end of the 20th century

This chapter presents a short overview of the international history of systemic risk in the 1980s and 1990s. To highlight its facets, we select particular systemic crises that occurred during those years. To show the international dimension of systemic risk, we look at systemic risk in both developing and developed countries. Our crises cover (all) different geographical regions (North America, Latin America, Europe, Asia, Australia, Middle East/Africa) and different mechanisms through which systemic risk manifests itself.1

A discussion of systemic risk before the global financial crisis is interesting because the experiences of developed countries is very different from those of developing countries. Systemic crisis events have been rare in developing countries, and the literature has largely ignored systemic risk. However, the literature on developing countries has considered systemic risk aspects long before the global financial crisis of 2008 (see, e.g., Tenconi, 1993; Daumont et al., 2004; Honohan, 1993; Paulson, 1993).

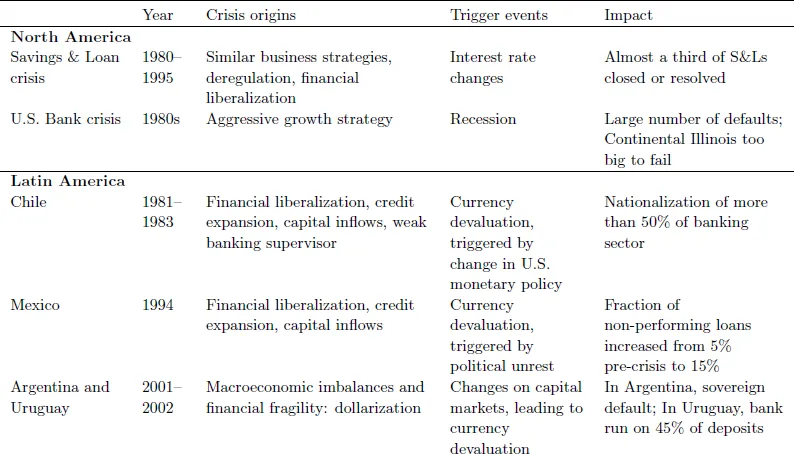

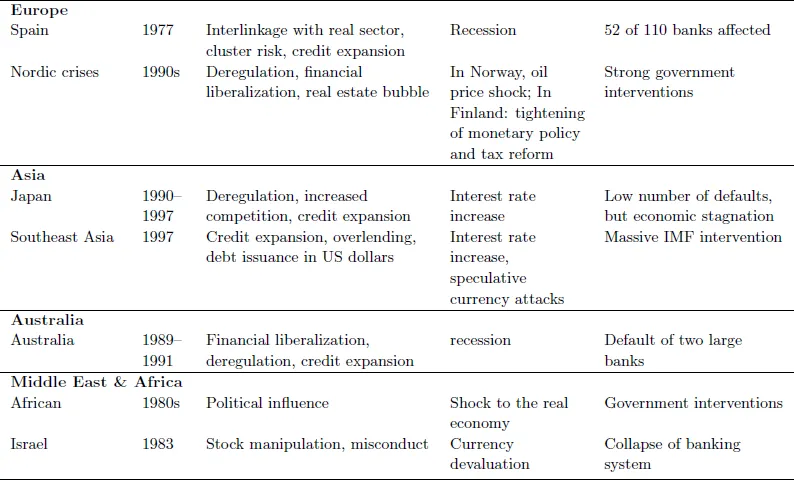

We start with North America in the first Section, where we analyze the Savings & Loan crisis and the U.S. bank crisis that led to the failure of the Continental Illinois Bank and Trust Company (Continental Illinois). We then turn to Latin America and present the systemic crises in Chile and Mexico, along with the crises in Argentina and Uruguay at the beginning of the 2000s. In Europe, we look at the Spanish crisis of 1977 and the Nordic crises of the 1990s. This is followed by an overview of the Japanese crisis in the 1990s and the Asian crisis of 1997. We then address the Australian crisis in 1990, briefly present aspects of systemic events in African countries and then turn toward the Israeli bank crisis of 1983. Table 1.1 provides an overview of the crises discussed in this chapter.

1.1North America

The 1970s were characterized by fundamental changes in the macro-economic environment, e.g., floating international exchange rates and increasing price levels due to oil shocks (see Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 1997, Chapter 1, p. 4). In the 1970s, the Federal Reserve Board raised short-term interest rates. Limits on deposit rates led to a financial innovation (money market funds) that offered higher returns than deposits. The withdrawal of funds from financial institutions created liquidity problems and decreased their profitability.

In addition, in the late 1970s, intrastate banking restrictions and regulations on deposit interest rates were lifted in the United States (e.g., through the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980). The financial liberalization caused significant changes in bank business strategies, and some banks experimented with highly speculative investments and assumed excessive risks.

We discuss first the Savings & Loan crisis and look at the failure of the Continental Illinois Bank and Trust Company (Continental Illinois). The source of the first crisis lies in financial liberalization and deregulation, while that of the second lies in an aggressive growth strategy. Both crises were triggered by the United States recessions from January 1980 to July 1980 and again from July 1981 to November 1982.

Table 1.1: Overview of systemic crises at the end of the 20th century.

1.1.1The Savings & Loan crisis

One of the most severe U.S. systemic crisis occurred in the 1980s: the Savings & Loan (S&L) crisis. Savings & Loan institutions are not-for-profit institutions that take on short-term deposits to finance long-term assets, usually mortgages (see, e.g., Robinson, 2013). For S&Ls, the simple intermediation between depositors and borrowers was quite profitable in the 1950s and 1960s. But in the 1970s, the Federal Reserve Board raised short-term interest rates significantly. As regulations limited deposit rates, depositors shifted their money from S&L deposits to money market funds (a financial innovation at that time). In addition to the depositors’ withdrawals, the interest rate increase caused a severe decline in the value of long-term (mortgage) loans. Since S&L institutions primarily gave out long-term loans, they lost a significant portion of their net worth through these interest rate increases (see, e.g., Robinson, 2013).

According to Robinson (2013), regulators were well aware of the losses in the S&L segment but lacked sufficient resources to deal with them.2 Instead, regulators hoped that a deregulation of the business would allow S&L institutions to become profitable again and outgrow their losses.

In 1980, the U.S. government initiated a process of financial liberalization in the Savings & Loan sector by passing the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of March 1980. This act significantly broadened the business (opportunities) for S&L institutions and allowed them to engage in transactions similar to banks. Many institutions engaged in risky investments without having adequate risk assessment and/or risk management (see, e.g., Ely, 1993). As the Savings & Loan crisis dragged on, more and more losses accumulated, leading to a large number of either closed or resolved institutions.

The crisis ended in the early 1990s, when interest rates declined and the yield curve turned upward again (see, e.g., Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 1997). Between 1986 and 1995, a total of 1,043 of 3,234 Savings & Loan associations closed or were resolved by the Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation or by the Resolution Trust Corporation (see, e.g., Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 1997, Chapter 4). The total cost of the Savings & Loan crisis is estimated at US-$160 billion, with US-$132 billion paid by taxpayers (see, e.g., Ely, 1993).

1.1.2Continental Illinois and the too-big-to-fail policy

While systemic risk in the 1980s and 1990s is often associated with the S&L crisis, another banking crisis occurred in the United States during the 1980s. During this crisis, more than 1,600 banks closed or received financial assistance from the FDIC (see, e.g., Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 1997, Chapter 1).

Between 1976 and 1980, Continental Illinois engaged in an aggressive growth strategy that increased both the size and the riskiness of its loan portfolio. When the United States entered a recession in July 1981 that lasted until November 1982, a large number of banks failed. The resulting banking crisis also affected several large banks. In July 1982, Continental Illinois had been close to failure when Penn Square Bank collapsed. While Continental Illinois did not collapse itself, the default of Penn Square Bank caused severe problems in Continental Illinois’ loan portfolio that continued for several months. In early May 1984, deposits of over US-$10 billion were withdrawn (see, e.g., Wall and Peterson, 1990; Carlson and Rose, 2016). Ultimately, Continental Illinois failed in 1984 when the bank could not obtain the renewal of short-term uninsured deposits.

At that time, Continental Illinois was among the ten largest banks in the United States, and almost 2,300 banks held deposits there or had loaned funds to the bank. Due to its size and its connectedness within the banking sector, Continental Illinois was the first institution to be officially considered too big to fail (see, e.g., Kaufman, 2003). The FDIC fully insured all creditors and depositors, as well as the parent holding company, and further provided new capital together with emergency loans (see, e.g., Yergin, 1991).

This decision symbolized a reversal in the FDIC’s policy on addressing failing banks. Previously, the FDIC paid only a portion of the amount owed to uninsured depositors (see Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, 1997, Chapter 7, p. 44). To prevent bank runs on other large U.S. banks, the FDIC decided to fully insure depositors and declared Continental Illinois as being too big to fail.

The policy of saving banks and financial institutions that were thought to be too big to fail remained in place until the Lehman Brothers default. During the 2007–2008 subprime mortgage crisis, most failing banks (such as Bear Stearns) were considered to be too big to fail and either received emergency liquidity (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) or were acquired by other financial institutions. While Lehman Brothers was perceived by the market as too big to fail, it was allowed to fail, which created turmoil among market participants (see, e.g., Paulson jr., 2010).

1.2Latin America

During the 1980s and 1990s, several Latin American economies experienced significant capital inflows followed by a capital flight that brought these countries (close) to default and destabilized their banking systems. While numerous crises occurred in Latin American countries,3 we choose to examine the systemic crises in Chile in the 1980s, in Mexico in the 1990s, and in Argentina and Uruguay at the beginning of the 2000s because all four countries share strong similarities and highlight the difficulties in identifying (increases in) systemic risk before a trigger event causes systemic crises.

The origins of these crises can be found in far-reaching financial liberalization, in fixed/pegged exchange rates in the cases of Chile and Mexico, as well as in financial fragilities (liability dollarization, ill-designed safety nets, and cross-border expositions) in the cases of Argentina and Uruguay. Significant capital inflows met a banking system that was ill prepared to handle a sudden supply of (cheap) money and that lacked regulatory supervision.

At first sight, the trigger event in these crises may be attributed to a change in the exchange rate, i.e., a macroeconomic shock affecting the whole banking system followed by a liquidity constraint. However, that exchange rate change was triggered by other events. In the case of Chile, the trigger was a change in U.S. monetary policy. In the case of Mexico, the trigger was an information shock in the form of political unrest. In the case of Argentina and Uruguay, the trigger was the failure to adequately address the currency-growth–debt trap into which these countries fell after devaluation of the Brazilian currency in January 1999.

1.2.1The Chilean crisis

The origins of the Chilean crisis of the 1980s date back to the 1970s. During that decade, the Chilean government implemented a series of neo-liberal economic reforms including (financial) liberalization and privatization. To achieve (comparatively) low levels of inflation, a fixed exchange rate regime with the U.S. dollar was installed in 1979; see, e.g., Barandiarian and Hernandez (1999), p. 12. Chile experienced a significant inflow of capital and commercial bank credit increased, see, e.g., Barandiarian and Hernandez (1999) and Margitich (1999), p. 39.

Risk management in banks did not adapt sufficiently to these structural changes (capital inflows, neo-liberal reforms, privatization of banks). Worse, Chilean banks in general faced limited incentives to implement adequate risk assessment strategies since the Chilean government had previously built a reputation of bailing out failing banks, e.g., SINAP in 1974 (Brook, 2000). Moreover, the banking supervisor (Superintendency of banks and financial institutions, SBIF) was weak, either through institutional weakening (depletion of resources and attributions), through the application of a formal supervision approach that was inadequate, and through deficiencies in the process of licensing and supervision of the risks. Hence lending standards decreased and the inflow of commercial credit increased lending, even to low-quality borrowers.

Considering the depreciating pressure on the U.S. dollar during the 1970s, the fixed exchange rate caused an overvaluation of the Chilean peso. Moreover, with its fixed exchange rate, Chile became increasingly dependent on U.S. monetary policy. When the U.S. dollar started to rise in 1980, capital inflows to Chile stopped and a recession started. In November 1981, the bank crisis became evident when two banks had to be bailed out by the government, with several minor banks following until early 1983 (Montiel, 2014, p. 32).

Downward price rigidity impeded a real depreciation of the Chilean peso. This created political pressure to devalue, so that in 1982 the fixed exchange rate regime was abandoned. A large nominal depreciation resulted, that affected the payment capacity of highly (external) indebted companies. This led to a systemic banking crisis. By 1985, 14 of 26 national banks and 8 of 17 financial institutions had been nationalized, i.e., the Chilean government owned more than 50 percent of the banking system (Brook, 2000, p. 76).

1.2.2The Mexican peso crisis

In the 1980s, Mexico started a process of financial liberalization (major structural reforms, privatization, and deregulation). From 1989 onward, it had further adopted a crawling peg exchange rate to the U.S. dollar that ultimately led to an overvaluation of the Mexican peso in international currency markets; see, e.g., Griffith-Jones (1997), Turrent (2008), Edwards (1996).

The Mexican banking system was ill prepared to deal with the subsequent capi...