![]()

CHAPTER ONE

COMMUNITIES

We are One, We are Singaporeans

The year was 1930 and Peter William Benson was beside himself with excitement. He had just scored a coup for journalism in Singapore – an interview with Sir Cecil Clementi, the new Governor of the Straits Settlements, no less.

His colleague Khoo Teng Soon recalled that Benson, who was Indian, “had a huge paunch, drank a lot of gin and tonic, had money problems and smoked cheap cheroots”. Khoo added, however, that Benson was very good at his job as a reporter with The Malaya Tribune and had “great contacts” in the police force.

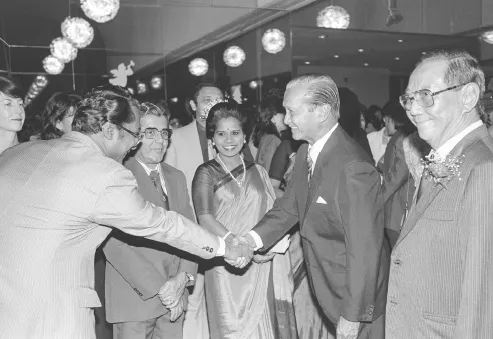

Khoo Teng Soon (far right, standing next to President Wee Kim Wee), better known as T.S. Khoo, at the Singapore Press Club’s annual dinner and dance in 1985. Khoo was a colleague of reporter Peter William Benson at The Malaya Tribune.

So off Benson went for the interview at Government House. Alas, he was out within seconds. “Clementi had never granted an interview to any local reporter,” Khoo said. “That is, until Benson wrote to him for an interview. Clementi obviously looked at that name – Peter W. Benson – and decided that Benson must be an expat. And of course, when he got into Government House, Clementi took one look at him and ordered him out.”

During his time in Singapore between 1930 and 1934, Clementi tried to stamp out the spread of anti-colonial sentiments by censoring the vernacular press. He also stopped the local Chinese community’s efforts to raise funds for China in their fight against the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War and angered the Peranakan Chinese with his anti-Chinese education and immigration policies. After Clementi prohibited education grants for Chinese and Tamil vernacular schools, only the Malay community received free education. Khoo mused: “Those were the days when you could have these types of governors.”

Governor of the Straits Settlements Sir Cecil Clementi (1929–1934) was apparently disdainful of locals.

Such prejudice, however, went beyond racist governors of the time. Frederick Arthur Chua, one of Singapore’s pioneering judges, recalled that when he returned to Singapore in the 1930s with a law degree from Britain’s Cambridge University, he was not accepted into Singapore’s circle of expatriates. Chua said: “Young people like me did not mix with the expatriates, only the older people and business people. We youngsters who just graduated, we didn’t mix with the expats. We didn’t socialise with them and we didn’t get invited either.”

Chua also recalled in the 2013 book, Legal Tenor: Legal Voices from Singapore’s Legal History 1930–1959, that when he worked in the Straits Settlements Civil Service from 1937 1942 in the Municipal Building – now part of the National Gallery Singapore – he and his local colleagues had a toilet to themselves. That was because they were barred from sharing a lavatory with white folk.

Khoo remembered other forms of racial discrimination. His first job was as a ledger clerk at Cold Storage supermarket in 1938 where the Centrepoint shopping mall sits today. “Very few locals patronised it,” he recalled. “Unless you were a big name, you would never have an account there because they were very, very discriminating.” Luckily for the locals, shops such as Kee Mun and Koon Heng sold frozen foods to rival Cold Storage, albeit on a much smaller scale.

He added: “Nine out of 10 of Cold Storage customers were expats; I knew this from going through the everyday bills in the ledger… the highest a local worker at Cold Storage could aspire to was Chief Clerk – but you still could not get a staff discount!” Despite such blatant discrimination, Khoo stuck it out as Cold Storage paid him $30 a month – big money in those days when a plate of chicken biryani was 25 cents. His salary, however, was nowhere near that of his expat colleagues. The average young expat earned between $200 and $250 a month then.

Khoo eventually switched to a career in journalism in August 1938 as that paid him $40 a month, with an additional monthly travel allowance of $15. His nose for news led to his promotion as the first local chief sub-editor of The Straits Times in 1951. By then, his expat peers were drawing between $600 and $800 a month, while he and other locals had to get by on a third of those salaries.

Joseph Anthony Desker, who worked in the Colonial Secretary’s office in Singapore after World War II, recalled that in the colonial government, even locals who were graduates could not rise above the level of chief clerk. The exceptions were professionals such as doctors, or lawyers such as Chua, who became the second local-born judge of the Supreme Court of Singapore on 15 February 1957. “So,” Desker added, “we knew that our career was limited. The attitude towards us was that we were to be subservient.”

That all changed when Singapore attained self-government in June 1959. The new government, formed by the People’s Action Party, carried out the policy of Malayanisation – the exercise of replacing expatriates with local talents in all ranks of government, especially those at senior levels. Desker found Malayanisation a sea change: “There was greater cooperation and friendliness. We knew who we were talking to. We belonged, perhaps, to the same community. We understood one another and so there was greater rapport between the junior staff and the senior officers.”

There remained, however, the expectation of a certain decorum between junior and senior staff. When journalist Tan Wee Him first reported for work at The Straits Times on 1 May 1970, one of the first colleagues he met was the paper’s news editor Sit Yin Fong. Tan recalled: “I went into his room and he was standing behind his desk and extending his hand. ‘Sit here,’ he said referring to himself by his surname. So I sat immediately in the chair in front of him – leaving a bewildered Mr Sit standing, with his hand outstretched.”

The relationship between masters and their apprentices was not always straightforward. Chua Eng Cheow, a master potter who was an expert at firing ceramic wares in dragon kilns, recalled how master potters would guard their secrets jealously. “It was their rice bowl and if they taught their skills to others, it would threaten their livelihood. Hence, we apprentices had to depend on our imagination and secret observations instead.”

Of Buffalos, Goats, Pigs and Crabs

In early Singapore, before the advent of assembly-line labour, communities were often defined by their occupations. Many Bengalis were milkmen, taking their kerbau, or buffalos, from door to door to provide households with the freshest milk. Tamilians tended to be goatherds who also sold their livestock’s milk door to door. Kannusamy s/o Pakirisamy, who was born in 1914, remembered these men well. In their birth country India, some among them had been indomitable Rajput warriors (members of a high-class Hindu military caste). But by the 1930s, some businessmen in Singapore began importing Australian-bred cattle, rendering the Bengalis’ business redundant. “The milkmen lost their jobs and the Bengalis among them became watchmen for bungalows and stores owned by Chinese contractors,” Kannusamy recalled.

The Tamilians, he added, turned to building roads and other infrastructure. “There were eight road contractors who were very well-known in Serangoon Road,” he said. “They included Muthiar Mandore, Veriah Mandore and Doraisamy Mandore.” The word mandore is from the Portuguese mandador, which means “overseer” or “one who gives orders”.

Sometimes, people from different communities did not address one another by their given names. Shuki Ram Chandra née Davies recalled how her brothers would spar with their schoolmates. “It was very common for Chinese boys to call the Indian boys nandu, which means ‘crab’ in Tamil. And the Indian boys would call the Chinese pandi, which is Tamil for ‘pig’. There were no fights about that, nothing. But now, the moment something is a little off-colour, there’s an eruption.”

Newsman and ex-professional boxer Lim Kee Chan contrasted the behaviour of hot-headed youths these days with gangsters of yore and recalled that the gangsters, at least, abided by certain principles. “Nowadays,” Lim said, “you see teenagers in a staring incident and they want to fight, kill each other. That is very sad.

An itinerant goat milk seller in Serangoon Road seen here decanting fresh milk for customers, 1982.

“In those days,” he added, “if you wanted to get a few gangsters to bash somebody up, they wouldn’t do it unless you gave them a good reason. They would keep asking you, ‘Why do you want to hit him?’ If you didn’t have a good reason, they wouldn’t do it. But now, for a cup of coffee, people would hammer each other.”

Mrs Chandra said remarks made by some communities about others were downright outrageous. “I have watched certain mothers telling their children in public, in their mother tongue, ‘not to go there because there is that keling kwai’.” Keling kwai is a derogatory Cantonese phrase referring to Indians. “Maybe some people think that Indian children might be dirty or black or whatever, so don’t mix with them. But that is not good; we are one, we are Singaporeans.”

However subtle racism might be these days, some feel its undercurrent. Artist Liu Chao, a new citizen of Singapore from Shenyang, China, said: “I have a gut feeling that even though we live in harmony, there is still some sense that we all have our own communities.” Curiously, Liu added, he felt more at home in the homes of non-Chinese Singaporeans than in Chinese households. For instance, he turned down invitations to celebrate the Mooncake Festival with Chinese families “because it’s a kind of a family reunion and their home is not mine”. Yet he was happy to eat in the homes of his Malay friends “quite a few times”.

Same but Different

Almost every city in the world has a Chinatown. Soh Siew Cheong grew up in Singapore’s version of it and recalled how the area was carved out among the Chinese clans. In his childhood, gangsterism was rife and if, say, a Hokkien crossed into Cantonese territory, it would be at his or her peril. This was easier said than done, as one wrong turn into a street controlled by a rival gang could end in bloodshed.

University librarian Vilasini Perumbulavil thought differently: she thought that the Chinese as a whole, regardless of their clan or dialect group, had more in common than their Indian counterparts. “You have Hokkiens, Teochews, Cantonese and so on but at least you have one unifying thing, which is your script. For us, there is no unifying factor… a Punjabi and a Malayalee could be from different countries. Their customs are so different. The things that they eat are different, they look different, their colour is different. Would Tamils and Malayalees feel at home in Punjab, Sindh or Bengal? Each is completely different and they write and speak differently.”

Khoo Teng Soon marvelled at how his maternal grandparents remained married for decades although neither spoke each other’s language. His maternal grandfather was Chew Boon Lay, after whom Boon Lay housing estate is named. Chew spoke only Hokkien, while his wife was Peranakan and spoke only Malay. “For years,” Khoo mused, “we had this curious situation where the old man could speak only Hokkien and hardly any Malay whereas my grandmother could speak only Baba Malay without being able to speak Hokkien. Despite all that, they produced 13 children.” And while Chew was against gambling, he was blind and so his wife would sneak out for chap ji kee (Hokkien for “12 cards”), or illegal lottery sessions.

Outside the family, there were distinctive clans within the same community. In the case of Malay-Muslims, each clan was known for certain attributes, occupations and even dishes. Haji Mohamed Sidek Bin Siraj, a civil servant turned Haj pilgrimage officer, said that the Malays, for example, were always called on to adjudicate disputes. Such disputes might include fights between the Bugis and the Banjarese over women within the community because, as he put it, “the Banjarese brought their women along with them while the Bugis didn’t.” The Baweanese, he added, were often stable hands and when cars replaced horse carriages, they became chauffeurs.

The Minangkabau of Sumatra brought nasi padang (rice served with various side dishes) to Singapore, while those who sold satay or grilled skewered meat were primarily Javanese. “They were not commercial-minded and liked their businesses to stay on a small scale,” he mused. And the mee goreng (Malay for fried noodles) so associated with the Indian Muslims today was actually introduced to Singapore by the Banjarese.

Despite these differences, Mohamed Sidek said that everyone in the Malay community were “united during kenduris, births, deaths, marriages, prayers and circumcision ceremonies”. Beyond that, it was not uncommon to see Malays pile into bullock carts to watch bangsawan, or traditional Malay opera, at the Royal Theatre in North Bridge Road, for $1 to $3 per person.

Different but Same

Mohamed Sidek also recalled how the Malay community took a live-and-let-live attitude towards mainland Chinese who began settling in Kampong Glam, the seat of Malay culture in Singapore, in the 1920s. “The Chinese started moving into the Kampong Glam area from 1922 after the visit of the Prince of Wales to Singapore,” he said. “Life in China was too hard so the Chinese began setting up small businesses in Kampong Glam.”

The Malays, he added, were not perturbed by these newcomers because “they didn’t come in hordes”. He noted that the Chinese immigrants just opened sundry shops, selling provisions that satay sellers and other Malay stallholders needed, acquired the Malay language and could even speak Javanese.

In fact, Mohamed Sidek added, the lingua franca for Singapore well into the late 1960s was Malay, and both Chinese and Indian traders used Malay as the language of trade. Dhanalakshmi Govindasamy, daughter of the ...