- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

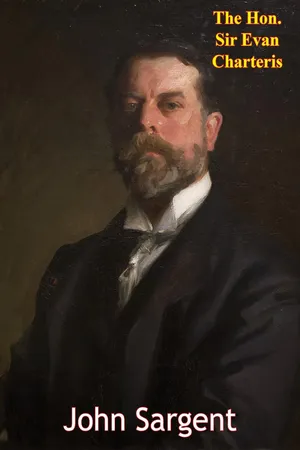

John Sargent

About this book

The career of John Sargent, perhaps the greatest painter of his time, and surely one of the greatest portrayers and interpreters of it in his famous portraits of its most eminent and most representative figures, is here chronicled in successive stages.

The figure of the hero stands out in high relief from the narrative which his personality pervades. A wealth of anecdote and of letters enriches the record of work, travel, and triumph, from student days under Carolus-Duran to the time when the presidency of the Royal Academy could have been his; and in all this opulent detail the character of the man overshadows even the distinction of the artist as the true theme of the book.

The figure of the hero stands out in high relief from the narrative which his personality pervades. A wealth of anecdote and of letters enriches the record of work, travel, and triumph, from student days under Carolus-Duran to the time when the presidency of the Royal Academy could have been his; and in all this opulent detail the character of the man overshadows even the distinction of the artist as the true theme of the book.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art GeneralCHAPTER I

JOHN SINGER SARGENT was born at the Casa Arretini in Florence, on January 12, 1856. The house stands on the Lung’ Arno, within a stone’s-throw of the Ponte Vecchio. Facing its windows, and on the other side of the river, there rises out of the waters of the Arno a row of houses whose walls here and there, tinted by age to the colour of amber, carry the tones of the river up to the russet roofs with which they are crowned. Above these, again, can be seen Bellosguardo, Monte Alle Croce, and away to the east the outpost foothills of the Apennines.

The father of John Sargent was FitzWilliam Sargent, who was born at Gloucester, Massachusetts, January 17, 1820. FitzWilliam Sargent graduated in medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in 1843. From 1844 to 1854 he was surgeon of Wills Hospital, Philadelphia. Eminent in his profession, he published works on minor surgery, in their day textbooks in the medical schools of America, which he illustrated himself. He was, above all things, American. In his frequent writings on political topics, patriotism was the guiding influence; nor was this affected by his migration to Europe. On June 27, 1850, he married Mary Newbold, the only child of John Singer, of Philadelphia, and Mary, daughter of William and Mary Newbold, also of Philadelphia. Lineage and early indications of promise acquire significance when they culminate in a master talent.

The genealogy of John Sargent calls for more than a passing reference.

On the paternal side John Sargent’s descent can be traced back to William Sargent, who was born in England, and appears in the town records of Gloucester, U. S., as the grantee of two acres of land in 1678. Nothing is known of his career. It can only be presumed that he was a mariner, as in 1693 he was taxed as owner of a sloop. It is known, however, that he married in Gloucester, on June 21, 1678, Mary, daughter of Peter Duncan and Mary Epes of Gloucester. The English ancestry of Mary Duncan has been traced with certainty. Her family originally came from Devonshire. There is a Peter Duncan who was instituted to the rectory of Lidford, Devon, in 1580. His son, Nathaniel Duncan, married in 1616 at the Parish Church of St. Mary Arches, Exeter, Elizabeth, daughter of Ignatius Jourdain. In 1630 Nathaniel Duncan, his wife and two sons, sailed for America. It is therefore to a Puritan stock that John Sargent traces his origin, to a family which, when the call came “for the church to fly to the wilderness,” joined those devout and ardent spirits, who, with John Winthrop at their head, migrated to the colony of Massachusetts in order to practise with greater freedom the austerities of their religion.

The descendants of William Sargent and Mary Duncan, through their third son, Epes Sargent (born 1690), have shown themselves honourable and efficient citizens of the United States, never reaching to any outstanding eminence, but maintaining a certain ordered and reputable level of intellectual activity, and following their professions with success. They have figured in law and commerce, in medicine and literature, as artists, as soldiers in the War of Independence, and as captains in the Merchant Service. Included among these descendants of Epes Sargent, in addition to John Singer Sargent, the subject of this memoir, may be mentioned that prolific writer, Epes Sargent (1813-80), remembered as the author of “Life on the Ocean Wave,” and Charles Sprague Sargent, born 1841, the distinguished authority on forestry and horticulture, who was drawn by John Sargent in 1919. All these descendants of Epes Sargent show a fine regard for obligations in private life and public service, and for duty as part of the very order and nature of existence. Strands of this Puritan thread, varying with environment and occasion, and adapted to new strains, enter into the web and woof of the family history.

On the side of his mother, Mary Newbold, his ancestry can be traced to Caspar Singer, of the Moravian belief, who migrated from Alsace-Lorraine to America in 1730. The descendant in the sixth generation of this Caspar Singer, namely John Singer, the grandfather of the artist, married Mary New-bold, daughter of a family which had moved from Yorkshire to America in 1680. John Singer himself was a well-to-do merchant, successor to a prosperous business which he had inherited from his father. Thus the ancestry of John Sargent has been domiciled in America on the paternal side since 1630, and on his mother’s side since 1730—the one originating in Devonshire, the other in Yorkshire. The mother of John Sargent was a woman of culture and an excellent musician. She also painted in water-colour. She was vivacious and restless in disposition, quickly acquiring ascendancy in any circle in which she was placed. In her family she was a dominating influence. She was one of the first to recognize the genius of her son, and in a large measure responsible for his dedication to art. As a girl she had travelled in Italy. The magic of that country never ceased to exercise its spell, and within four years of her marriage she persuaded her husband to give up his practice, and in 1854 to sail for Europe and take up their residence in Florence. FitzWilliam Sargent had, by his practice in Philadelphia, made himself of independent means. His wife, Mary Newbold, was sufficiently well off to render the pursuit of his profession on financial grounds unnecessary.

Europe, in the words of Henry James,{1} had by this time been “made easy for” Americans. Just as in the seventeenth century the drift of movement had been from East to West, so now, two hundred years later, the tide had turned; and the drift, under conditions and directed by motives in no way comparable, it is true, had set from America to Europe. The new world, animated by the impulse to track culture to its sources and discover for itself the origins of artistic inspiration, had begun that steady pilgrimage which, not always with the same object in view, has continued to the present day. But by the middle of the nineteenth century “the precursors” had accomplished their work—not the work of settlers and backwoodsmen, as in the case of their forbears—but the sorting and registering of the first contacts and preliminary adjustments between a new civilization and an old. The traditions, the institutions and customs of Europe had been reported upon by numberless explorers, and its highly specialized complications had been tested and, if not mastered, at least successfully confronted. Migration to Europe was an established practice. Rome and Florence already bore abundant witness to the process of American infiltration. It was, therefore, as an already recognized type of pilgrim that the Sargent family arrived in the old world; though it was long before they were to find a last and settled home in Europe. The Continent, with its provocations to restlessness and its various appeals, tempted them for many years to constant movement: Florence, Rome, Nice, Switzerland, the watering-places of Germany, Spain, Paris, Pau, London and again Italy, were in turn visited by the family in their wanderings.

It would be of interest if we could estimate the effect of these nomadic habits on the fancy of a child and trace the results in his maturity. It would be an error to deny them some influence. Europe, passing as it were on a film, must have dwarfed the sentiment of early associations, and tended to slacken the hold of locality and even tradition. At any rate, it is possible to find in Sargent’s art qualities certainly congruous with such an exceptionally restless childhood.

A letter written in 1863 or 1864 by FitzWilliam Sargent to his parents throws light on the upbringing of John Sargent, and the influence of Channing, Emerson, and ten years of wandering in Europe on a New Englander’s view of the Scottish Catechism.

“The boy (John) is very well; I can’t say he is very fond of reading. Although he reads pretty well, he is more fond of play than of books. And herein, I must say, I think he shows good sense. I have just sent him after a book to read for a half-hour, to keep him in trim, so to speak, and after a while I shall trot him out for a walk on the hills. I think his muscles and bones are of more consequence to him, at his age, than his brains; I dare say the latter will take care of themselves. I keep him well supplied with interesting books of natural history, of which he is very fond, containing well-drawn pictures of birds and animals, with a sufficient amount of text to interest him in their habits, etc. He is quite a close observer of animated nature, so much so that, by carefully comparing what he sees with what he reads in his books, he is enabled to distinguish the birds which he sees about where he happens to be. Thus, you see, I am enabled to cultivate his memory and his observing and discriminating faculties without his being bothered with the disagreeable notion that he is actually studying, which idea, to a child, must be a great nuisance. We keep them all (the children) supplied with nice little books of Bible stories, so that they are pretty well posted-up in their theology. I have not taught them the Catechism, as someone told me I should. I can’t imagine anything more dull and doleful to a little child, than to be regularly taught the Catechism. You may teach them who made them; you may give them a correct idea, so far as you can understand it yourself, and make them comprehend it, of God and of our Saviour, and of the sacrifice of Christ for sin and sinners; you may teach them the nature and meaning of Sin, and of our need of a Saviour; of Death and of Everlasting Life, etc. But I am sure it would bore me dreadfully to be obliged to learn the Catechism, although I hope I know all that it contains pretty well. I remember that Mr. Boardman once asked me, at a Sunday school examination, “What is the chief end of man?” and I told him Death, at which he professed to feel some surprise, and I know my teacher, good Mr. McIntyre, (the little man who afterwards seceded), supposed I had made an extraordinary mistake. But the fault was not mine, but the stupid wording of the question; if I had been asked, what was the object of God in creating man, I had sense enough to have been able to give a correct reply. And so Emily and Johnny I believe, can give the substance of everything in the Catechism important for them to know, as yet, or which they can, as yet, to any good degree comprehend, without inspiring them with a dislike to books in general by making them “go through” the Catechism. I confess (and I hope you will not be hurt) that I am not able myself to give the exact replies to the questions of the Catechism. To me it is the dreariest of all books.”

In 1862 the family was at Nice at the Maison Virello, Rue Grimaldi. In a neighbouring house with an adjoining garden was living Rafael del Castillo, of Spanish descent, whose family had settled in Cuba and subsequently become naturalized Americans. Rafael’s son Benjamin was of an age with John Sargent, and from this date the two became close friends. He also made friends in these early days with the sons of Admiral Case, of the American Navy, and with Mr. and Mrs. Paget, and their daughter Violet (Vernon Lee). With these and others John Sargent and his sister Emily (born at Rome in 1857) were constant associates.

Patriotic motives decided FitzWilliam Sargent to send his son into the Navy. The arrival of United States ships of war at Nice gave a chance of testing the boy’s taste for the sea. But it was found that he was much more interested in drawing the ships than in acquiring knowledge about them.

The fire within him, burning to record and express, was already at work. Every day was quickening his powers of observation and his precocious aptitude. In a letter written in 1865 to his friend, Ben del Castillo, while the family were vainly seeking a climate that might restore the health of a sister, Mary Winthrop (born at Nice, 1860), he shows the alertness of his visual faculty.

PAU,

April 16, 1865.

DEAR BEN,

“We got to Pau on Wednesday. We stayed at Toulouse a day, and Mamma took Emily and me to the Museum, and we saw the horn of Roland, and the pole and wheels of a Roman chariot, and many pictures and statues. The next day we got to Bordeaux in the afternoon, where Mamma took Emily and me to the Cathedral, where King Richard the 2nd of England was married to an Austrian princess. The windows of the Cathedral were filled with beautiful stained glass; one of the windows was round, and the glass was of a great many colours. The cathedral is very old. Bordeaux is a fine old city. The quai on which our hotel was is very wide, and the river has a great lot of large ships in it and a great many steamers. We left so early the next morning that I had not time to draw any of them; but they would have been too difficult for me, I think. In crossing the Landes from Cette to Toulouse, and between Bordeaux and Pau, we saw many sheep, and the shepherds were sometimes walking on stilts, very high, so that they may see further over the Landes while their sheep are feeding. Near Cette we saw a lot of storks on the shore of the sea which runs up into the country, and there was one very large lake with several towns on its banks. The name of this lake is Etang, and I believe that one of the towns is called Aigues Mortes.

“We came from Bordeaux to Pau by rail-way in about five hours. We had very cold rooms in the hotel, and the weather was very bad for a while; it snowed every day for more than a week, and sometimes it snowed very hard, but the snow melted directly. After that, the weather cleared up, and we had s...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- PREFACE

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- CHAPTER I

- CHAPTER II

- CHAPTER III

- CHAPTER IV

- CHAPTER V

- CHAPTER VI

- CHAPTER VII

- CHAPTER VIII

- CHAPTER IX

- CHAPTER X

- CHAPTER XI

- CHAPTER XII

- CHAPTER XIII

- CHAPTER XIV

- CHAPTER XV

- CHAPTER XVI

- CHAPTER XVII

- CHAPTER XVIII

- CHAPTER XIX

- CHAPTER XX

- CHAPTER XXI

- CHAPTER XXII

- CHAPTER XXIII

- CHAPTER XXIV

- CHAPTER XXV

- CHAPTER XXVI

- CHAPTER XXVII

- J. S. S.-IN MEMORIAM

- SARGENT’S PICTURES IN OILS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access John Sargent by The Hon. Sir Evan Charteris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.