1

THE STATE OF STATE AUTHORITY

Northern Uganda is a striking place. Bordered by Kenya on the East, the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the West, and what was formerly southern Sudan in the North, the region claims about 35% of Uganda’s total land mass and about 20% of its population. Economic activity consists primarily of agriculture and, in the semiarid region of Karamoja, pastoralism centered on cattle keeping. Though it is not rich in exploitable mineral resources, the North is a place of great natural beauty. It is the home of several national parks and wild-life preserves, and is traversed by the White Nile, one of the two tributaries of Africa’s most famous river.

Northern Uganda is also severely undergoverned. Those familiar with Uganda’s history may not find the unevenness of the state’s reach surprising. The country’s North-South divide has roots in British policies from the colonial period, which favored the South and marginalized the North. Yet colonial legacies are not destiny. Uganda’s first leaders after independence in 1962—Apollo Milton Obote, his more infamous successor Idi Amin, and the short-tenured Tito Okello—all hailed from the North. When Yoweri Museveni and his National Resistance Movement (NRM) won control of the country in 1986 after the five-year Uganda Bush War, the locus of political power shifted to the South. Recognizing the potential political threat of the North to the security of his new government, Museveni and the NRM sought to consolidate state authority throughout the country.1

At least in the North, these efforts have largely failed. A report prepared by the World Bank in 1992, six years after the NRM’s victory, illuminates the degree of the state authority deficit:

The affected districts have been to a large extent cut off from the rest of the country since the end of 1986, with the result that line ministry officials have had very limited access to their field staff. It has been difficult for government programs and projects to be implemented in the area, especially where ambushes by rebels and bandits were common…. Local authorities have been only able to raise tiny amounts of revenue because of the poverty of the population and the breakdown of marketing, transport, and revenue collection. Many local posts have gone unfilled and many officials have been unable to get out into the field to do their jobs.2

As we see in this excerpt, state authority was elusive. Even as the rest of Uganda made impressive strides in consolidating state authority and promoting economic and human development elsewhere, the North languished. In a 2010 interview with the U.S.-based Center for Global Development, Makerere University professor Julius Kiiza noted the ongoing challenges of political and economic development in northern Uganda, pointing to the state’s lack of monopoly of violence, lack of fiscal control, and lack of service provision.3 In short, Uganda continues to be an example of a country with limited state authority over territory.

What is state authority, and what is the state of state authority in the post-1945 era? The goal of this chapter is to address these questions. As I suggested in the introduction, state weakness has often been understood primarily as a deficiency in the capability of the central state’s bureaucratic and administrative institutions. This book concerns itself with a different dimension of state weakness: the territorial reach of the state’s authority. Because state authority over territory has, until recently, received less attention in the literature, this chapter begins by defining this concept. I then move from the abstract to the concrete, providing an overview of the prevalence of ungoverned and partially governed spaces in the contemporary international system. I then show what life is like in areas where the state’s authority is limited or absent, and contrast human welfare conditions in under-governed spaces with those in governed spaces. As we will see, weak state authority characterizes a large number of states in the contemporary international system. I leave to the following chapter the task of explaining why such spaces persist.

The Exercise of State Authority

To exercise state authority is to govern: to make and enforce rules and regulations, and to provide services. The world’s early states did little in administrative terms other than levy taxes, provide a modicum of security, and occasionally conscript soldiers. The modern state, however, is distinguished by a significant expansion in the scope of state activities.4 Today’s states are expected to regulate, enforce, tax, protect, and provide, and to do so evenly across the full extent of their territories. When the state governs all of its territory, its authority is consolidated. When the state’s authority is limited, contested, or absent altogether in particular parts of its territory, those spaces are undergoverned or ungoverned from the perspective of the state.

This last point is worth emphasizing: in this book, the term “ungoverned” refers to an absence of state authority, not an absence of authority altogether. It is not always the case that spaces devoid of state authority exist in a pure condition of anarchy. For example, in a well-researched study, Zachariah Mampilly documented the phenomenon of rebel rulers, who govern in lieu of the state.5 If the Hobbesian state of nature is not completely a myth, it is certainly an empirical rarity. This is true even for Somalia after the 1990s, a state that many political scientists and analysts consider to be the prototypical “failed state.”6 Somaliland and Puntland, two of Somalia’s unrecognized states, are examples of spaces where alternative authorities administer and control territory. These spaces are governed. They are not governed by the state.7

The exercise of state authority requires the presence of the state in the form of state bureaucrats and physical infrastructure such as roads, government offices, and public schools and primary health facilities. A state that is not administratively present cannot govern, because the business of governing requires that the state interact with its population in order to induce or compel their compliance with rules and regulations. Think of the tax assessor, who must have access to taxpayer assets in order to calculate the taxes owed to the state. Historically the work of the tax assessor and his similarly reviled counterpart, the tax collector, required face-to-face interactions with taxpayers. In many developing countries, especially those in which postal and online systems are not well functioning, taxation still entails this kind of interaction. Or consider the beat cop who patrols a neighborhood, or the soldier sent to quell violence and restore order. Even mundane governance activities such as registering births or applying for a construction permit entail some form of interaction between the state and its population.

This definition of state authority, which concerns itself with the territorial penetration of the state, is akin to what Stephen Krasner refers to as “domestic sovereignty.” In Krasner’s conceptualization of sovereignty, domestic sovereignty is both the organization of public (state) authority and the degree to which it is exercised effectively.8 There are many ways to think about the meaning of effective state authority. Although there are exceptions, a great deal of the literature on state development and state capacity concerns itself with the quality of the state’s central administrative institutions. Administrative institutions hold primacy of place both for scholars who recognize the multidimensionality of state capacity as a concept and for scholars who understand state capacity as a form of power.9 For them, state weakness is a deficiency in the power and strength of state administrative institutions, or what I call state institutionalization.10 Denmark has well-developed, high-quality administrative institutions. Uganda does not. Somalia, an extreme case, effectively has no administrative institutions at all.

This book studies effective state authority in terms of its evenness over territory, rather than its intensity or quality. Scholars such as Jeffrey Herbst, Guillermo O’Donnell, and Michael Mann are all interested in understanding the spatial extent of state power.11 I call this state consolidation. Can the state provide order throughout its territory? Can the state collect taxes throughout its territory? Can the state regulate throughout its territory? The Ugandan state governs, but it does not govern evenly. It is quite effective at ensuring stability in some parts of its territory, but it is quite ineffective at doing so elsewhere, and can be classified as unconsolidated. Its presence in its citizens’ lives depends very much on where those citizens live.

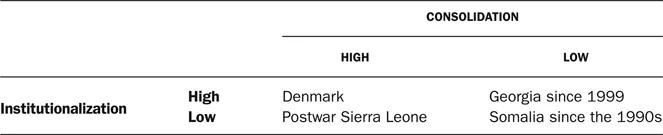

Importantly, state institutionalization and consolidation do not necessarily move together. Table 1.1 arrays the possibilities. The countries most people consider to be developed states are both institutionalized and consolidated. Denmark has a high degree of administrative capability and it effectively exercises authority throughout its territory. Countries commonly referred to as failed states, like Somalia, lack administrative capabilities and do not govern the entirety of their territories. The more interesting cases are those in between. Since the end of its civil war, Sierra Leone has scored low on institutionalization but high on consolidation. Its administrative institutions are weak, but weak as it is, the state’s reach extends evenly throughout its territory. No doubt the country’s small size makes the task of governance easier. In contrast, Georgia since 1999 has scored high on institutionalization but low on consolidation. It inherited bureaucratic institutions from the Soviet period and strengthened these in the 1990s. However, Georgia exhibits marked unevenness in the territorial reach of the state, to the point where alternative claimants to power exclude Georgian state authorities from large swaths of Georgia’s territory in the North.

TABLE 1.1 State institutionalization versus state consolidation

Both institutionalization and consolidation are constitutive of the state. They are important conceptually and in welfare terms, but represent different approaches to understanding what makes a state a state, and offer different standards of evaluation. They also present different dilemmas for would-be state-builders, whether foreign or domestic: the causes of weak institutionalization and low consolidation are not necessarily the same, nor are the solutions necessarily the same. Indeed, this book breaks from much of the literature by distinguishing between these aspects of the state and showing that conflictual foreign pressures undermine consolidation.

Measuring Spatial Variation in State Authority

How prevalent are gaps in state authority across space and time? This is not an easy question to answer. To do so, we have to know how to identify incomplete state consolidation when we see it. Political scientists often look for the consequences of state weakness: where the ill effects of weak statehood are present, state authority must be limited or absent. This approach informs the widespread use of infant mortality as a proxy for state authority.12 Scholars consider infant mortality to be the canary in the state authority coal mine. We know that this measure correlates highly with state weakness and, at least in developing countries, depends on state authority due to the state’s central role in providing primary health services. Another common method to identify a lack of state authority is to look at violence. Where we observe political violence, we know that the state is not providing order, and is therefore failing to execute a fundamental state function.

The practice of looking at outcomes of weak statehood is not a bad approach, but it is subject to some important limitations. Most data, for example, are available at the national level. National data are useful for identifying countries with incomplete state consolidation but not for identifying where within those countries the state’s authority is limited. Subnational data have only recently become available for many outcomes related to state authority, and are often subject to missingness precisely because state authority is low.

In fact, the state’s inability to collect accurate information about its population can actually tell us something about where and to what degree the state exercises authority. All states, including the world’s earliest states, seek to gather information about the people the state purports to rule. Information is crucial for the effective exercise of state authority, as states need information for planning, monitoring, and enforcement across a wide variety of domains.13 In ancient times, this information was often a simple count of the population. The Bible, for example, tells of King David’s census of the people of Israel, which was conducted in part to facilitate military conscription. Ancient China and Rome also counted the...