- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Chicago Artist Colonies

About this book

For more than a century, Chicago's leading painters, sculptors, writers, actors, dancers and architects congregated together in close-knit artistic enclaves. After the Columbian Exposition, they set up shop in places like Lambert Tree Studios and the 57th Street Artist Colony. Nationally renowned figures like Theodore Dreiser, Margaret Anderson, Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Sullivan became colleagues, confidants and neighbors. In the 1920s, Carl Sandburg, Emma Goldman, Ernest Hemingway, Ben Hecht, Edna St. Vincent Millay and Clarence Darrow transformed the speakeasies and bohemian bistros of Towertown into Chicago's Greenwich Village. In Old Town, Renaissance man Edgar Miller and progressive architect Andrew Rebori collaborated on the Frank Fisher Studios, one of the finest examples of Art Moderne architecture in the country. From Nellie Walker to Roger Ebert, Keith Stolte visits Chicago's ascendant artistic spirits in their chosen sanctuaries.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

ArtSubtopic

Art GeneralPart I

Chicago in the Nineteenth Century

A Cultural Backwater Striving to Catch Up

1

The Arts in Chicago Before the Fair

On the evening of October 8, 1871, a fire broke out in a barn on the southwest side of Chicago. Within two days, the fire quickly spread and destroyed extensive portions of the city, razed 17,000 buildings and caused an estimated $200 million in damages. The fire left more than 300 people dead and more than 100,000 homeless. It destroyed all the belongings of poor and rich alike, without distinction. That was the bad news. The good news was that the Great Chicago Fire provided Chicagoans with a unique opportunity to remake their city into a better, safer and more habitable place, which they did with gusto within weeks following the conflagration that leveled the city.

One thing the fire did not destroy in any appreciable degree were works of art made by artists in Chicago—because there was very little art made in the city between the time of its incorporation in 1837 and that fateful and fiery October evening. The paintings and prints hanging on the burning mansion walls of Chicago’s wealthy citizens did not come from Chicago, they came from New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Paris, London, Munich and the ancient cities of Italy. Prior to the fire, city directories identified only a few dozen residents as artists, but most of these were not engaged with the creation of fine art. They were more likely involved in the day-today commercial industries of sign-making, interior millwork and decoration, and rendering graphics for newspapers, periodicals and what little product packaging existed at the time.

GEORGE PETER ALEXANDER HEALY

The only painter of any more than a piddling reputation who lived and worked in Chicago before the fire had already left the city a few years before and was residing in Europe, not to return on a permanent basis for more than two decades. Fortunately, he took many of his paintings with him or otherwise sent them elsewhere in the United States, so they survived the Great Fire and now grace the walls of the White House, the U.S. Capitol and some of the nation’s most respected art and history museums. George Peter Alexander Healy was born in Boston in 1813, grew up in near poverty and had little early formal instruction in art. Nevertheless, at age nineteen he persuaded Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis, the reigning queen of Boston society, to sit for a portrait. That portrait at once made his reputation in Boston, and he was soon exhibiting his paintings, mainly portraits, at the Boston Athenaeum.3

The following year (1834), Healy sailed for Paris and entered the studio of Baron Antoine-Jean Gros. By 1840, Healy had become a fashionable portrait painter in a city full of artistic talent, and he was given sittings by the French king, Louis Philippe. The king was so pleased with his portrait that he sent young Healy to England to copy some of the paintings in Windsor Castle and later to America to copy Gilbert Stuart’s full-length portrait of George Washington and portraits of other prominent Americans.4

Healy became a quasi-official painter to Louis Philippe’s court until the revolution of 1848 put an end to the French monarchy (for the second time) and Healy’s royal patronage. By that time, the collection of Healy’s portraits at Versailles, either copies of earlier works or his original paintings, included portraits of such luminaries as Queen Elizabeth I, King George III, William Pitt, Admiral Horatio Nelson, George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay.5

Healy remained in Paris following the revolution, but his subject matter was decidedly American, capturing famous statesmen in historic and dramatic scenes. For example, in 1851, Healy painted his monumental picture of Daniel Webster replying to Senator Robert Hayne on the powers of the federal government, regarded by many as one of the most eloquent speeches ever delivered in Congress, which hangs in Faneuil Hall in Boston.

Healy’s painting representing Benjamin Franklin exhorting Louis XVI for alliance and resources during the American Revolution won a gold medal at the exhibition of 1855, the highest honor yet awarded to an American artist.6 So, George Healy’s international reputation was already firmly established when, at about the same time, he made the acquaintance of William Butler Ogden, an early settler to Chicago, builder of railroads, real estate magnate and the city’s first mayor—and, of course, the subject of a Healy portrait.

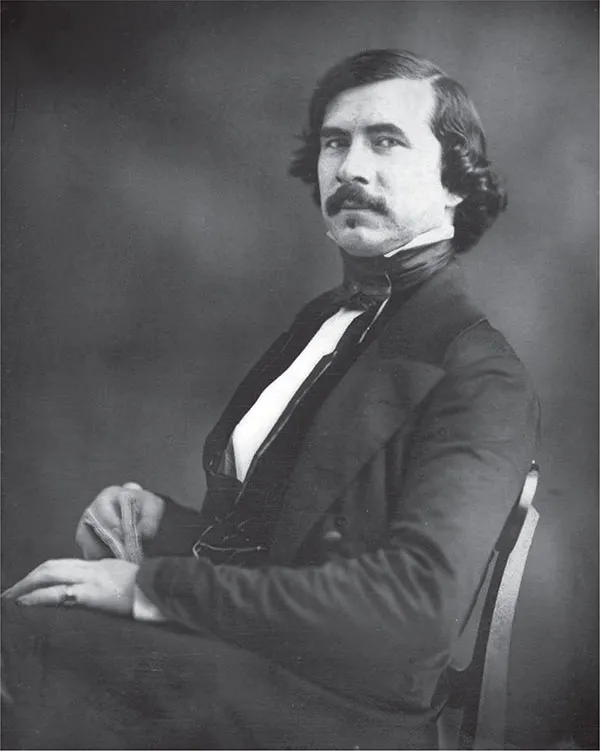

George Peter Alexander Healy. Southworth & Hawes (1852), Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Ogden, the son of a successful lumber merchant, had been trained in the law and served in the New York legislature in 1834. The next year, he was sent to Chicago by a consortium of eastern investors to supervise large parcels of landholdings in the area. Chicagoans found this handsome newcomer from New York urbane, educated, charming and quick-witted. He was also ambitious. Upon the city’s incorporation in 1837, the citizenry elected William Ogden as their first mayor. His real estate management work led Ogden to the management of the Illinois and Michigan Canal and, later, to the region’s burgeoning system of railroads. He was a founder of the Galena and Chicago Union Railroad, Chicago’s first rail line, and the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad. He was appointed the first president of the Union Pacific, which Ogden used to extend the reach of Chicago’s rail lines to the West Coast. Ogden’s impressive accomplishments were largely fueled by his ability to persuade New York investors and Midwest farmers to part with millions of dollars to fund his real estate and transportation enterprises.

Having made a large fortune early in his career, Ogden then involved himself in every civic and cultural endeavor worth joining in Chicago until he died in 1877. He also amassed a large and valuable art collection, starting in the 1850s. His collection came to include works by prominent East Coast artists such as Frederic Edwin Church, Hiram Powers, John Frederick Kensett, Jasper Cropsey and Asher Durand. The latter’s 1852 painting Landscape After a Shower was probably the first work by a major American artist that graced a Chicago home. Ogden also collected Old Master paintings from Europe.

When William Ogden sat for his portrait in the Paris studio of George Healy in 1855, the famous expatriate painter could not have anticipated the powers of persuasion that this silver-tongued Chicago pioneer and businessman could unleash in the name of civic pride. Over several meetings with Healy, Ogden made the clarion call for Healy to abandon his successful portrait studio in Paris and take up digs in the young, rough frontier city of the Midwest badly in need of art and culture.

Ogden succeeded in persuading Healy to visit Chicago in the fall of 1855. In short order, several leading Chicagoans commissioned Healy to paint their portraits and those of their families. In his Reminiscences, Healy wrote that he intended to stay in the city only a short time, but the pressure Ogden and other prominent Chicagoans exerted on him, and the professional and pecuniary success he almost immediately enjoyed in Chicago, finally led Healy to move his family from Paris and make Chicago his new home.7

Healy remained in the Chicago area for fourteen years. For the first two years, Healy and his family lived in a house in the city, but in 1857, he erected a large home in what became the suburb of Elmhurst, reportedly the first house ever built there, and maintained a studio on Lake Street in Chicago. Healy moved his family back to the city in 1863, to a house located at the intersection of Washington Street and Wabash Avenue, where he remained until 1869.8

In 1857, the U.S. Congress commissioned George Healy to paint a series of portraits of American presidents. During the next two or three years, Healy traveled extensively throughout the United States and painted his presidential portraits as well as dozens of other commissioned portraits of prominent Americans. The presidential series included paintings of John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, John Tyler, James Polk, Franklin Pierce, Millard Filmore and James Buchanan. In 1860, Healy was commissioned to paint the first of many portraits he would ultimately make of Abraham Lincoln, who had recently been elected president. This was his famous portrait of Lincoln, beardless, painted in Springfield. Although Healy would paint many of the most well-known portraits of Lincoln, his 1860 painting was the only one for which Lincoln would actually sit.

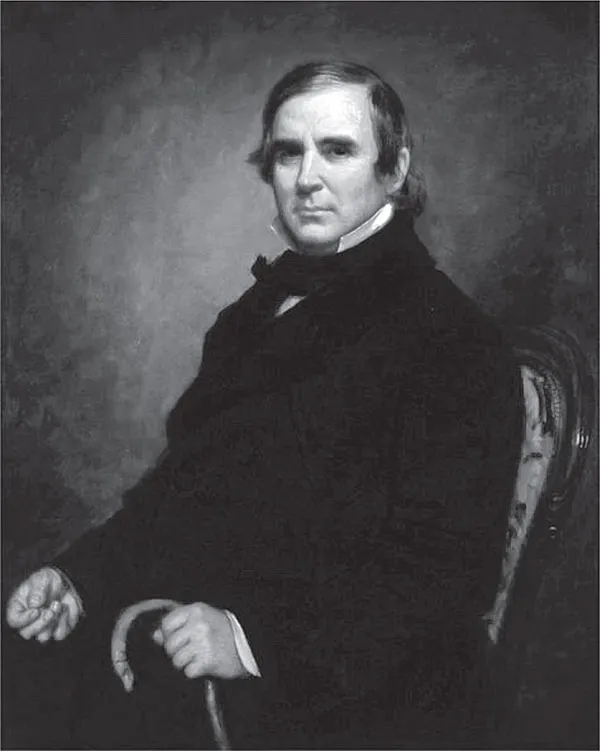

Portrait of William Ogden, painted by George P.A. Healy (1855). Chicago History Museum.

During his fourteen years living and working in Chicago, Healy was to paint six hundred canvases of a veritable who’s who of American society, politics and culture. In addition to those Americans identified so far, Healy painted portraits of most members of Chicago’s Blue Book, including Mayor John “Long John” Wentworth, businessmen William Blair, E.W. Blatchford, Cyrus McCormick, Martin Ryerson and their wives. He painted Civil War generals U.S. Grant and William Sherman and U.S. politicians Daniel Webster, John Calhoun, Henry Clay, William Seward and Elihu Washburne. His work included portraits of writers Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Europeans Franz Liszt, Otto Von Bismarck, a handful of British nobles and the King and Queen of Romania were portrayed in his prodigious opus.

LEONARD WELLS VOLK

George Healy was not just the North Star of Chicago culture during his decade-and-a-half residency in the area; he was virtually the only star. The only other artist of note prior to the Great Fire was Leonard Wells Volk, a sculptor. Born in Wellstown, New York, in 1828, Volk was first a marble cutter, together with his father, in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where the family had moved. In 1855, Volk married Emily King Barlow, whose maternal cousin was Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, a powerful leader of the U.S. Senate and participant in the famous Lincoln/Douglas debates of 1858. Douglas was a wealthy landowner in Chicago and a founder of the Illinois Central Railroad. Through Douglas’s benevolence, Volk was able to travel in 1855 to Rome to study sculpture.9

Returning to the United States two years later, Volk and his family settled in Chicago. During a visit by Abraham Lincoln to the city in the spring of 1860, Volk asked the candidate for the Republic nomination for president to sit for a bust. Volk then made one of two life masks of Lincoln (the other was made by Clark Mills in 1865). Lincoln was quite pleased with the final bust, declaring it to be “the animal himself.” The life mask (and casts of Lincoln’s hands Volk made in the summer of 1860) gave Volk a creative advantage—he used the life mask, hand casts and finished bust to create later versions of Lincoln after his death, including a life-sized statute.

During his years in Chicago, Volk executed several statues or busts of famous Chicagoans and others. For example, he made a life-sized statue of his wife’s cousin, Senator Douglas, which was ultimately placed on a tall pedestal near Thirty-Fifth Street over Douglas’s tomb. Volk created statutes of Douglas and Lincoln for the Illinois State Capitol in Springfield, Illinois, and a statue of General James Shield for the U.S. Capitol.10 Likenesses of local dignitaries Elihu Washburne, David Davis and Zachariah Chandler also took form under Volk’s chisel.11

Although they had opened and operated successful studios in Chicago, both George Healy and Leonard Volk decried the paucity of art and culture in their newly adopted city. Healy said he intended to make “an art center” in Chicago, but, apart from the prodigious outpourings of portraits by his own hand, there is little evidence that he or the city succeeded in attracting other painters of any consequence. Before 1860, there were no art schools, exhibition halls or art dealers. Wealthy Chicagoans purchased (or brought with them when they settled in the city) paintings, prints and sculptural works of East Coast and European artists. Therefore, when in 1858 Leonard Volk encouraged the city fathers to consider staging a major public art exhibition in Chicago, it was generally acknowledged that the art to be displayed would be loans of works of East Coast and European artists from the private collections of wealthy citizens.

THE ART EXHIBITION OF 1859

Following a meeting at the Chicago Historical Society on March 22, 1859, the organizing committee issued a notice of a plan for an art exhibition “to consist of such select and approved paintings and sculptures as are in the possession of our citizens, in order to afford to the public, and especially to all persons interested in the Fine Arts, an opportunity to gratify and improve their taste in art matters.”12 A board of directors was appointed, and Volk was selected as curator with primary responsibility for exercising control over the standards of art established by the directors and Volk. On April 12, newspaper advertisements seeking contributions of art appeared and formal invitations were sent to persons “whose wealth and good taste have put them in the possession of choice pieces of statuary or well-conceived and well executed paintings.”

Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted addressed certain reservations of some of Chicago’s elite that levels of good taste among the general citizenry might be too lacking for a high-quality exhibition: “Having all migrated to the West while young and lived for a while on the very frontier…you might expect them to be very different from what they are. In fact, the[ir] children are clever and well-bred. They are rather sensitive about the West and Chicago, lest anyone should think that people are not likely to be as informed and cultivated as anywhere.”13 Editor and critic James Spencer Dickerson pointed out that the elite of Chicago had always been formed of people of education and culture, even in its earliest days. “Among the earliest settlors of Chicago, even in the 1830s, were people of refinement.” Many early settlers, such as William Ogden, Walter Newberry, Eliphalet Blatchford and John Wentworth, came from wealthy cultured families in the East and received good liberal educations, before migrating to the new city on the prairie. Indeed, even the first permanent white settler, fur trader John Kinzie, brought his violin when he and his small family came to Chicago in 1803.

Paint and chemical manufacturer Alexan...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword, by Amy E. Keller and Zac Bleicher

- Introduction

- PART I: CHICAGO IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: A CULTURAL BACKWATER STRIVING TO CATCH UP

- PART II: ARTIST COLONIES OF THE CHICAGO AREA

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Chicago Artist Colonies by Keith M. Stolte in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.