eBook - ePub

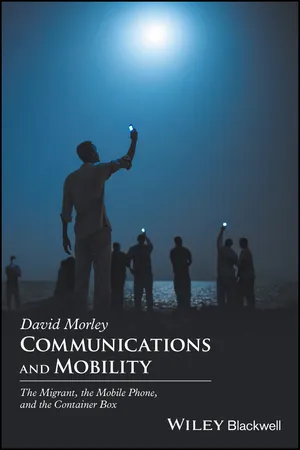

Communications and Mobility

The Migrant, the Mobile Phone, and the Container Box

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Communications and Mobility is a unique, interdisciplinary look at mobility, territory, communication, and transport in the 21 st century with extended case studies of three icons of this era: the mobile phone, the migrant, and the container box.

- Urges scholars in media and communication to return to broader conceptions of the field that include mobility of all kinds—information, people, and commodities

- Embraces perspectives from media studies, science and technology studies, sociology, media anthropology, and cultural geography

- Discusses ideas of virtual and embodied mobility, network geographies, de-territorialization, sedentarism, nomadology, connectivity, containment, and exclusion

- Integrates the often-neglected transport studies into contemporary communication studies and theories of globalization

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Communications and Mobility by David Morley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Return of Geopolitics

1

Communications, Transport, and Territory

Introduction

An old dictionary I have at home defines communications as “an act of imparting (esp. news); information given; intercourse; common door or passage or road or rail or telegraph between places.”1 This older definition encompasses not only the symbolic realm – which is what we nowadays tend to think of first when the question of communication arises – but also the field of transport studies. It was in this spirit that Marx and Engels defined communication broadly enough to include the movement of commodities, people, information, and capital – including within their remit not only the instruments for transmitting information but also the material transportation infrastructures of their day. As Marx argued, the “creation of the physical conditions of exchange,” and in particular, of the railways, was a necessity for the development of nineteenth century capital, insofar as it allowed products to be converted into “uprooted” commodities as they were transported beyond their region of production into more distant areas. To that extent “the railroad was to travel as industry was to manufacture.” In the Grundrisse, Marx argues that it is precisely transportation between geographical points which turns objects into commodities, arguing that “this locational movement – the bringing of the product to the market, which is the necessary precondition of its circulation … could more precisely be regarded as the transformation of the product into a commodity.”2

Marx and Engels’ concern was with the connections between the technologies for transmitting messages and transporting commodities and people, all of which was seen as part of a broader, geopolitical “science of territory” – a set of concerns which are readily re‐codable into contemporary debates about deterritorialization and reterritorialization. Evidently, nowadays, the territories and technologies concerned are virtual as much as material, but I shall argue that, far from living in a supposedly “post‐geographical” age, geographies, of one sort or the other, continue to matter, if now in different ways. In this context, I will argue that what is needed is a re‐excavation of the tradition of work that continues Marx and Engels’ concerns with the constitutive powers of systems of communications and transport.3

The Power of Metaphor

In 1933 the art historian Rolf Arnheim proposed that the new invention of television was best understood metaphorically, in relation to questions of physical transport – as a “means of distribution” – but of images and sounds rather than of objects or persons. To this extent, he argued, television is fundamentally related to modes of transport such as the motor car and the airplane – but in this case, as a “means of transport for the mind.”4 Evidently, Arnheim’s argument works at the level of metaphor by transposing the function of physical modes of transport to the virtual sphere, where the entities being transported – images and ideas – are themselves immaterial. If we trace the etymology of the word “metaphor,” we find that its original Greek meaning is precisely to “transport” or “carry across” – in this case, to transfer significance, by using a figure of speech in which a name or descriptive term is transposed from one realm of meaning to another. As Jonathan Sterne observes, some of our central terms for discussing these matters already invoke the concept of “communication as a subspecies of movement.” Thus, Bruno Latour notes that “the word metaphoros is written on all [furniture‐ DM] moving vans in Greece” for the simple reason that the English term “metaphor” derives from the Greek words for “to transfer or carry.”5 To take another example, if many cab drivers in the metropolitan cities of the West are immigrants who have come from elsewhere and then take a job moving the city’s residents around, then these “metaphorical” processes are doubly condensed in the figure of the immigrant taxi driver.6 Arnheim’s proposition is further extended by Ben Bachmair, who is concerned with the particular relationship between motor car and the television as “mobile” media – which have, in combination, transformed the pace, pattern, and scale of social life in the twentieth century.7 He argues that television fitted snugly into – and extended – the mobile lifestyles encouraged by the motorcar. Furthermore, he insists that the symbiotic relationship between the television and the motorcar should be seen as parallel to that between the telegraph and the railway system in the earlier era.8

Passengers, Readers, Drivers, and Spectators

In English, the word “transport” can refer either to this material form of motion, in which a person or thing is moved from A to B, or to the immaterial process in which, for instance, the reader of a novel is mentally “transported” to another (in this case, fictional) realm. These two different dimensions were notably brought together at the moment in the nineteenth century when the coming of the railways in Britain, and thus the particular mode of “passive/comfortable” travel they allowed, created a market for train reading – and thus for the emergence of platform‐based newsagents in railway stations. Henceforth, the railway traveller/reader could be simultaneously “transported” in both these dimensions.9 In his work on the coming of the railway in the earlier period, Wolfgang Schivelbusch shows how the new experience of moving through the landscape at high speed created a different form of “proto‐cinematic” vision for the seated passenger, who is personally immobile and yet transported elsewhere. To this extent, the train (and later the car), as well as the various screens of the media, can be seen to have contributed to the development of a specifically modern subjectivity of accelerated visual stimulation.10

Within the field of media and cinema studies, some authors, such as Margaret Morse and Anne Friedberg, have, in recent years, begun to address the relationship between the visual experience of physical mobility, when landscapes are viewed through the window of a car, ship, train, or plane and forms of media spectatorship of moving images. Thus Morse considers the analogous nature of the experiences of vision through the car windscreen on a motorway, through the display windows in a shopping mall and that provided by the television screen. Friedberg is similarly concerned with the parallels between the visual experiences of the car driver and the cinema/television spectators. As she notes, drawing on the work of both Baudrillard and Virilio, if the “cinema provides a virtual mobility for its spectators, producing the illusion of transport to other times and places,” the driver is themselves physically immobile, cocooned in the comfort of the “audiovisual vehicle” in which they traverse material space, while “the surrounding landscape [unfolds] like a televised screen.” Thus she explores what she calls the “framed visuality” of the car windscreen, cinema, television, and computer screens as modes of spectatorship all shaped by their relation to the architectural form of the screen/window.11

To this extent, I would argue that the exploration of these metaphors, linking previously ignored dimensions of the relationships between communications and transport, can potentially be very productive.12 However, if, as George Lakoff argued many years ago, metaphors are what we “live by” insofar as they structure our thought at a very fundamental level,13 we do always need to be careful in their deployment as they sometimes hide as much as they reveal. We should be very careful, as I will argue later following Sara Ahmed, to avoid the dangers of reducing the material processes of migrancy to a superficially convenient metaphor for “mobility” in the abstract, as if it were the “essence” of the contemporary world. We are not all mobile in the same way, and my ambition here is to spell out the significant differences between our various engagements in the different forms of virtual and actual mobility and stasis.14

In relation to questions of material and metaphorical distance, our concerns must be, as Birgitta Frello argues, with the specifically social dimensions according to which mobility is given meaning – which always occur within specific relations of power. The question is not simply that of empirically “mapping” material issues such as distance, speed, and means of transport. It is also a matter of the socially constructed discourses through which places – and the differences and distances between them – are defined as “here” or “there.” The question then is “where or what … or how far away is ‘there.’”15 The further questions concern how geographical proximity or distance is ar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Redefining Communications

- Part I: The Return of Geopolitics

- Part II: Reconceptualizing Communications: Mobilities and Geographies

- Part III: The Mobility of People, Information, and Commodities: Case Studies in Communications Geography

- Index

- End User License Agreement