![]()

Chapter 1

Growing Your Teaching Effectiveness

An Overview

DOES THE FOLLOWING DESCRIPTION FIT YOU?

You want to know how you are teaching, so if need be, you can make appropriate changes that will improve your teaching and students’ learning. Like most other teachers, you start by looking at your most recent student evaluations and see that less than 40 percent of the students completed the online course evaluation. Is this a representative sample? Did more of the disgruntled group complete the evaluation than those who were satisfied? Did the really bright students who worked hard in the course evaluate it? Do the answers to the items on the survey instrument address those questions? Your summary scores on the quantitative questions indicate slightly above-average scores compared with other faculty in your department and college; however, the range on some of the questions is fairly large. Moreover, the comments do not offer any real insights. Several students say you are a nice person or a good teacher who treats students fairly. A few students remark that that the course was challenging. To students, “challenging” implies that the instructor made them work hard (Lauer, 2012). Is that a compliment or a complaint? One student did not like how you dress. A few felt the course would be better if it had been scheduled at a different time. What can you learn from feedback like this?

Feeling a little frustrated at the lack of concrete feedback from students, you look at the recent peer observations of your teaching (provided this feedback is available). The comments consistently say that your class was well organized, you know the material, and you maintain a good pace. Your peers note that your rapport with the students is good considering the size of the class, but they suggest that calling on students more by name might help. One suggests using a bit more humor. Another observed that most of the students were paying attention most of the time, but from time to time they got distracted, talking with each other and texting or checking Facebook. Other than trying to use student names, you did not learn much else from this feedback.

What to do now? Your department chair does not offer advice because she has not made classroom visits, so you decide to talk with an esteemed senior colleague in your department. He attributes his success to respecting students as individuals. But what does that mean, and, more pragmatic, how does a teacher show respect for students and with more than two hundred of them spread across three classes?

If you have concluded that the common practices for seeking information to help teachers become more effective does not work, I agree. Current methods of evaluating teaching do not generate the data needed to make good choices about what and how to change teaching. We urgently need new strategies and new tools to provide information for this process.

The Goal: Promoting Excellent Teaching

The overarching purpose of this book is to promote teaching excellence, specifically your teaching excellence. When students are learning and the educational experience is going well, both students and teachers are invigorated. This book identifies many ways in which you can gain insights that will foster better student learning. Learning can be defined in many ways. To clarify, in this book, I am using the term to mean deep and intentional learning. Deep learners gain understanding of the content as opposed to just memorizing it. They form many associations with the concepts and can recall the information and use it to solve problems in the future (Ramsden, 2003). When students purposefully gain knowledge and skills, and learning is not just an incidental outcome, they are intentional learners. Intentional learners spend more effort than what is needed to complete a task in a superficial way (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1989). Intentional learning is the goal of all higher education, especially the general education curriculum according to the Association of American Colleges and Universities (2002). Effective teaching promotes both deep and intentional learning.

Many professors have not been trained how to teach. In graduate school, they learned the knowledge and skills of their disciplines and engaged in research. But they know little about how students learn generally or how they learn content. It is not surprising that some of these instructors are dissatisfied with the quality of their teaching. They aspire to be excellent teachers (Austin, Sorcinelli, & McDaniels, 2007) but discover that good teaching takes a lot of time—time that they may need to devote to do research. For professors who experience this stress, this book offers constructive ways to teach and how to improve it.

Are you hesitant about spending time developing your teaching skills? Given the pressures to conduct research, advise students, serve on committees, and respond to family responsibilities, you may think there is not enough time left to devote to developing your teaching. However, research shows that developing your teaching is an investment that pays off (Austin et al., 2007). This is an ongoing process, and you can devote a little time to teaching growth each month. In fact, small amounts of time continually are probably better than thinking you will focus on your teaching only during semester breaks.

After identifying ways to change how you teach, as suggested in this book, you may find that your faculty development or teaching and learning center are very helpful. These centers regularly offer programs that address specific aspects of teaching, and chances are good that you’ll meet other instructors concerned about improving their teaching. They may become colleagues to work with as you continue your quest for excellent teaching.

Better Teaching throughout Your Career

Academics need different kinds of instructional information at various times during their careers. Those at the very beginning need basic help in how to teach. Junior faculty members may spend too much time on their teaching without being very effective (Austin et al., 2007). Feedback is most helpful in the early years of academic careers if it is oriented more to development than evaluation (Rice & Sorcinelli, 2002). A few years later, as assistant professors approach tenure review, they may find using a systematic way to assess their teaching particularly useful, especially if it offers clear explanations of standards for good teaching (Austin et al., 2007). After tenure and sometimes when teaching the same courses repeatedly, though, professors can find their teaching becoming a little stale, so they may want some fresh ways of doing what has become perhaps overly familiar.

This book offers suggestions for teachers at all stages of their careers. It is a book for every teacher in higher education because every teacher can improve and every teacher should want to be the best teacher possible. The methods and tools described in this book can be especially helpful for assistant professors because they offer an organized and ongoing self-development process that can have huge payoffs if it is begun early in one’s career. Midcareer faculty, even very effective teachers, can use the model proposed in the book to continue their development as teachers. It works as well for teachers who may be struggling. Thus, faculty across the entire teaching career can benefit from this book.

Effective Strategies That Promote Better Teaching

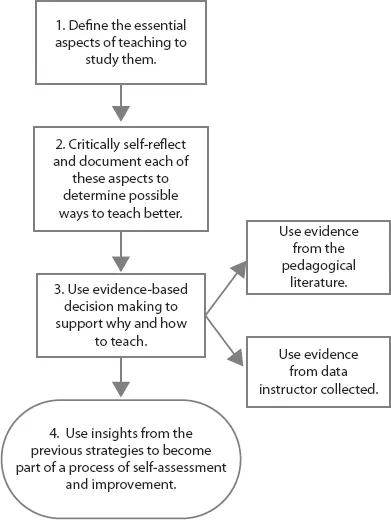

I believe that a hierarchical approach that places the locus of control with the instructor who wants to improve, rather than with others who need to judge teaching performance, provides a robust teaching enhancement process. This process best fosters the kind of teaching that promotes deep and intentional student learning. The approach I advocate integrates four well-supported and effective, but previously separate, teaching strategies. Each successive level is based on a separate strategy and incorporates data and insights for better teaching from the previous level. While much literature exists to support each of these strategies individually (Brew & Ginns, 2008; Brookfield, 1995; Kolb, 1984; Kreber, 2002), no one has yet suggested that the strategies be used together. Figure 1.1 shows how I integrate the strategies. Although the concepts of critical reflection with documentation, evidence-based decision making, and self-assessment are consistent with the standards of practice used in other professions and with accreditation standards, they are not commonly used to improve teaching. Using these four best practices strategies in a hierarchical way yields new insights that inform ways to advance teaching and learning.

In the following sections I summarize this process and note where you will find a detailed discussion of these concepts in this book.

Growth Strategy 1: Define the Essential Aspects of Teaching

In order to study teaching, you need to establish criteria that define teaching standards. Of the many descriptions of teaching, in this book I use Barr and Tagg’s (1995) learning-centered approach to teaching. They focus on what the instructor does to promote student learning, and not on the instructor’s behaviors as ends in themselves.

I categorize the essential aspects of effective teaching into three higher-order learning-centered guiding principles: the structure for teaching and learning itself, the instructor’s design responsibilities outside the direct teaching responsibilities, and assessment of learning outcomes. Each principle entails various components:

Guiding Principle of Structure for Teaching and Learning

1. Plan educational experiences to promote student learning.

2. Provide feedback to students.

3. Provide reflection opportunities for students.

4. Use consistent policies and processes to assess students.

5. Ensure students have successful learning experiences through your availability and accessibility.

Guiding Principle of Instructional Design Responsibilities

6. Conduct reviews and revisions of teaching.

Guiding Principle of Learning Outcomes

7. Assess student mastery of learning outcomes relating to acquisition of knowledge, skills, or values.

8. Assess student mastery of higher-order thinking and skills: application, critical thinking, and problem solving.

9. Assess student mastery of learning skills and self-assessment skills that can transcend disciplinary content.

These aspects of teaching are shared whether the teaching is didactic instruction, offered online, or experiential, as in clinical or studio settings. Chapter 3 discusses these essential aspects of teaching and the various experiential contexts for teaching.

Growth Strategy 2: Begin and Integrate the Study of Your Teaching with Critical Self-Reflection

Critical self-reflection and documentation of each of these aspects helps determine possible ways to improve teaching. The analysis of teaching through critical self-reflection promotes better teaching, which leads to increased student learning (Brookfield, 1995; Kreber, 2002).

I recommend analyzing your teaching philosophies and classroom policies to understand how your teaching affects student learning and attitudes. With a solid understanding of what, how, and why you teach, you can begin to see how to enhance your teaching. Critical self-reflection yields insights into your teaching that you can use to identify possible areas to change (Weimer, 2010). With those identified, you can prioritize the list and decide which ones to work on now and which ones can wait. This critical self-reflection is not the same as self-assessment of teaching. Chapter 4 describes the literature supporting critical self-reflection and how you can use it to promote better teaching.

Documentation of this self-analysis is a vital part of the process. This documentation should include a description of your rationale, how you communicate it to students, directions for assignments, and evidence that students achieved the learning outcomes. All of parts 2 and 3 of this book discuss this documentation process and the many benefits that accrue from using it.

Growth Strategy 3: Use Evidence to Support Teaching

A system that incorporates evidence-based decision making is superior to relying on perceptions alone (Brew & Ginns, 2008). The concept of evidence-based decision making is consistent with the literature on higher education (Shulman, 2004a, 2004b; Smith, 2001) and with the accreditation standards that professional and regional accrediting agencies use. Yet most instructors do not integrate these practices into their teaching (Handelsman et al., 2004). One reason is that current evaluation tools do not require or even suggest their use. Unless they are motivated by evaluation results, faculty frequently feel little reason to adopt practices that require more effort. The approach to better teaching described in this book uses evidence-based teaching as a standard criterion for all teaching. This strategy has two separate aspects: it recommends reading the literature on teaching effectiveness and advocates collecting data on your own teaching.

Use Pedagogical Literature

Perhaps more than any other strategy, reading the pedagogical literature on teaching and learning in higher education and in your own discipline can improve your teaching (Brew & Ginns, 2008; Weimer, 2006). Lee Shulman (2004a) defines teaching that is designed ba...