This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume of three books presents recent advances in modelling, planning and evaluating city logistics for sustainable and liveable cities based on the application of ICT (Information and Communication Technology) and ITS (Intelligent Transport Systems). It highlights modelling the behaviour of stakeholders who are involved in city logistics as well as planning and managing policy measures of city logistics including cooperative freight transport systems in public-private partnerships. Case studies of implementing and evaluating city logistics measures in terms of economic, social and environmental benefits from major cities around the world are also given.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access City Logistics 2 by Eiichi Taniguchi, Russell G. Thompson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Urban Planning & Landscaping. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Urban Logistics Spaces: What Models, What Uses and What Role for Public Authorities?

Despite the failure of initial attempts and still uncertain economic profitability, UCCs are continuing to develop in France and elsewhere in Europe. In this chapter, we show that there is no single solution but rather a whole range of urban logistics spaces between which local authorities must decide on the basis of the objectives assigned to these facilities. To do this, we propose the criteria to be taken into account and the institutional and regulatory measures that appear best adapted. We analyze the examples which we consider the most innovative, efficient and in tune with the changes occurring in lifestyles.

1.1. Introduction

The most widespread solutions for reducing the impact of goods delivery vehicles in cities (environmental, noise and safety) affect several domains. The most common are the land available for logistics activities, the pooling consolidation of flows, the implementation of restrictive regulations, the use of less pollutant vehicles better adapted for urban use, road sharing through time and by type of use, and performing studies to obtain better knowledge of flows and to design tools to evaluate measures [OEC 03, BES 07].

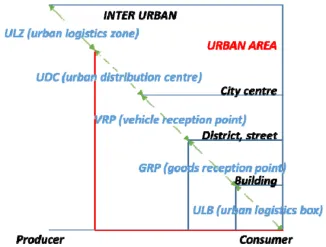

Among these solutions, the Urban Logistics Space (ULS), “a facility intended to optimize the delivery of goods in cities, on the functional and environmental levels, by setting up break-in-bulk points” [BOU 06], appears very interesting. It can be broken down into six categories: the Urban Logistics Zone (ULZ), the Urban Distribution Center (UDC), the Vehicle Reception Point (VRP), the Goods Reception Point (GRP), the Urban Logistics Box (ULB) and the “mobile” Urban Logistics Space (mULS). Each of these types of facility mirrors issues based on land (surface areas dedicated to logistics) and constitutes a place for pooling (equipment, m2 and transport capacities). Some ULSs allow for better distribution of flows over the day by dissociating the delivery by the transporter from the collection by the client, and privilege the use of “clean” vehicles for last-mile deliveries. ULSs thus allow optimizing urban goods deliveries and pickups through better filling of vehicles, more efficient round organization, fewer conflicts linked to infrastructure use regarding goods vehicle traffic and parking.

Thus, it is clear why urban logistics spaces have given rise to a multitude of studies and experiments, especially in the form taken by the “urban distribution center (UDC)”. In order to avoid any misunderstanding, we underline here that according to the typology formulated by Boudouin, these UDCs also encompass “urban consolidation centers (UCC)”. The aim of both the UDC and the UCC is to consolidate flows destined for the city. In the UDC, this is done by pooling several actors, often with the involvement of the public authorities. In the case of UCCs, they are specific to an economic sector or to a zone of the city. Despite the large number of experiments, few have latched on to a working economic model, as most have been abandoned or subsist only thanks to public subsidies. Nonetheless, these failures do not appear to discourage initiatives and ULS projects continue to emerge. The objective of this paper is to classify the different types of ULS and, for each of the six categories identified, specify their scope of application, the elements regarding implementation and/or operating costs, and detail the appropriate accompanying measures needed to favor their success. Examples of successes and failures are presented to highlight the key factors underlying the former and the reasons for the latter.

1.2. Literature review

The literature on ULSs can be divided into two categories. The most widely known is naturally that which focuses on the experiments carried out. It would be futile to try to provide a full panorama, thus emphasis will be placed on syntheses performed in the framework of projects aimed at proposing recommendations regarding good practice. The other category concerns theoretical documents, presenting models of logistics centers [BRO 05].

Between these two focal points, the French approach of categorizing ULSs, performed in the framework of the National Urban Goods Program (Ministry of Transport and the Agency for the Environment), is particularly singular. Indeed, it is both a conceptual and pragmatic perception that identifies models of facilities while providing an approach that uses a number of indicators to allow local actors to select those best adapted to the objectives desired. In addition, this classification of ULSs is based on taking into account the spatial dimension of the facility. By not setting a threshold on the surface area, the area of impact or the volume of goods handled, or applying rules regarding the institutional structure of these spaces, it is possible to group a whole array of facilities under the single denomination of ULS along with their respective scopes of application and between which urban actors can arbitrate to build their logistic framework. We obtain a typology of ULSs in five categories, now increased to six to integrate mobile ULSs [BOU 06, BOU 17], as a function of the objectives desired, the modifications introduced in the supply chain, the level of public involvement required to favor their implementation and their range of action.

Figure 1.1. The typology of ULSs [BOU 06]. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/taniguchi/cities2.zip

The literature has mainly focused on the concepts of UDC and UCC among the types of logistics spaces in this inventory. The generic term of ULS has essentially remained specific to France apart from a few exceptions (e.g. [DEO 14]). As for other variations of the ULS, concepts of freight villages have been observed in different countries, although they do not necessarily cover an essentially urban dimension. For the most part, the latter signifies areas enabling the intermodal transfer of goods at the national and international levels. However, the term “vehicle reception point” is used in several articles such as [VAN 14, BRI 12]. Likewise for the concept of “goods reception point” [JAN 13].

In Europe, the first experiments conducted to set up ULSs emerged in the United Kingdom in the 1970s. They involved the construction of Urban Consolidation Centers (UCC) by transporters, since the concept of ULS was deemed too expensive and likely to increase the volume of traffic linked to the use of large fleets of small vehicles to make last-mile deliveries [OEC 03]. Elsewhere in Europe, projects in this area were mainly carried out starting from the second half of the 1990s, mainly in the form of UDCs. About 150 were initiated, although few are still operating [SUG 11]. Mention can be made of the city of Padua whose Cityporto concept was adopted by other Italian cities: Modena, 2007, Como, 2009, Aosta, 2011 and Brescia, 2012 [LEO 15]. The United Kingdom, a pioneer regarding UCCs, also focused on their most efficient models: Heathrow, Bristol and London.

In this brief panorama, France was no exception to the ebullience stimulated by the concept of UDC and more generally ULS. Since the 1990s, 44 ULSs (excluding Goods Reception Points) have been identified. However, the evaluation of these realizations is harsh: seven projects have been abandoned and 10 have closed. Only 17 are still in service. Nonetheless, the concept continues to attract attention since eight are currently in the project phase [SER 15].

1.3. ULS typology

These failures indicate that the Urban Logistics Space should not be an end in itself. It only has substance if considered within the framework of a global analysis of the urban context leading to the selection of the type of ULS best adapted to local issues, independently of considerations of political leaning. Before making any decision as to the installation of a ULS, it is therefore advisable to perform a detailed diagnostic of needs, to specify the objectives assigned to the equipment and the institutional framework necessary to achieve them, and to examine the perimeter of pertinence in order to finally choose the suitable site.

According to the size of the city, the needs identified and the objectives pursued, the installation may require integration in a logistics master plan and a full overhaul of the regulations relating to transport and town planning. Marked differences can also exist regarding the size of the tools considered, the financial implications of the actors involved and the regulatory measures taken to facilitate their operation.

1.3.1. The Urban Logistics Zone (ULZ) or freight village

1.3.1.1. The concept

The freight village ensures the transit of goods between the city and interurban areas, and it provides the interface between modes of transport: railway/river/maritime/road. According to case they can be: enterprise zones comprising buildings or land made available for this purpose, agri-f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1 Urban Logistics Spaces: What Models, What Uses and What Role for Public Authorities?

- 2 Dynamic Management of Urban Last-Mile Deliveries

- 3 Stakeholders’ Roles for Business Modeling in a City Logistics Ecosystem: Towards a Conceptual Model

- 4 Establishing a Robust Urban Logistics Network at FEMSA through Stochastic Multi-Echelon Location Routing

- 5 An Evaluation Model of Operational and Cost Impacts of Off-Hours Deliveries in the City of São Paulo, Brazil

- 6 Application of the Bi-Level Location-Routing Problem for Post-Disaster Waste Collection

- 7 Next-Generation Commodity Flow Survey: A Pilot in Singapore

- 8 City Logistics and Clustering: Impacts of Using HDI and Taxes

- 9 Developing a Multi-Dimensional Poly-Parametric Typology for City Logistics

- 10 Multi-agent Simulation with Reinforcement Learning for Evaluating a Combination of City Logistics Policy Measures

- 11 Decision Support System for an Urban Distribution Center Using Agent-based Modeling: A Case Study of Yogyakarta Special Region Province, Indonesia

- 12 Evaluating the Relocation of an Urban Container Terminal

- 13 Multi-Agent Simulation Using Adaptive Dynamic Programing for Evaluating Urban Consolidation Centers

- 14 Use Patterns and Preferences for Charging Infrastructure for Battery Electric Vehicles in Commercial Fleets in the Hamburg Metropolitan Region

- 15 The Potential of Light Electric Vehicles for Specific Freight Flows: Insights from the Netherlands

- 16 Use of CNG for Urban Freight Transport: Comparisons Between France and Brazil

- 17 Using Cost–Benefit Analysis to Evaluate City Logistics Initiatives: An Application to Freight Consolidation in Small- and Mid-Sized Urban Areas

- 18 Assumptions of Social Cost–Benefit Analysis for Implementing Urban Freight Transport Measures

- 19 Barriers to the Adoption of an Urban Logistics Collaboration Process: A Case Study of the Saint-Etienne Urban Consolidation Centre

- 20 Logistics Sprawl Assessment Applied to Locational Planning: A Case Study in Palmas (Brazil)

- 21 Are Cities’ Delivery Spaces in the Right Places? Mapping Truck Load/Unload Locations

- List of Authors

- Index

- End User License Agreement