This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Evidence-based Implant Treatment Planning and Clinical Protocols

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Evidence-based Implant Treatment Planning and Clinical Protocols provides a systematic approach to making treatment decisions and performing restorative procedures.

- Offers a clinically relevant resource grounded in the latest research

- Applies an evidence-based approach to all aspects of implant dentistry, including maxillofacial prosthodontics, from planning to surgery and restoration

- Describes procedures in detail with accompanying images

- Covers all stages of treatment, from planning to execution

- Includes access to a companion website with video clips demonstrating procedures and the figures from the book in PowerPoint

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Evidence-based Implant Treatment Planning and Clinical Protocols by Steven J. Sadowsky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Dentistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The State of the Evidence in Implant Prosthodontics

Gary R. Goldstein

New York University College of Dentistry, New York, New York, USA

Introduction

Okay, you have been placing and/or restoring implants for numerous years and are pleased with your clinical outcomes and your patient acceptance of this exciting treatment modality. You attend a lecture or read an article about a new product or technique that claims to have a higher insertion torque, less bone loss, etc.; so, how do you decide if you should switch? The rubrics are very simple, so, whether you read a paper in a peer‐reviewed journal, a non‐peer‐reviewed journal, or hear it in a lecture, the rules are the same for all three.

There is a multitude of information available to the clinician, some evidence‐based, some theory‐based, some compelling and, unfortunately, some useless. Evidence‐based dentistry (EBD) gives one the tools to evaluate the literature and scientific presentations. It constructs a hierarchy of evidence which allows the reader to put what they are reading, or hearing, into perspective. As we proceed on this short trail together, I want to state that there is no substitute for your own clinical experience and common sense, and hope that when you are done with this chapter you will understand why. I am not here to trash the literature, rather to propose that not all published works are equal.

Hierarchy of evidence

EBD is a relatively new phenomenon that was introduced in the 1990s. It evolved slowly due to misunderstandings and misrepresentations of what it is and what it means, and, despite a slow start, has picked up traction and is now an ADA Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) requirement, mandatory in dental education and the backbone of clinical research and practice. Journal editors and reviewers are well versed in the process and less likely to approve the methodologically flawed project for publication, putting more pressure on the researcher to pay heed to research design.

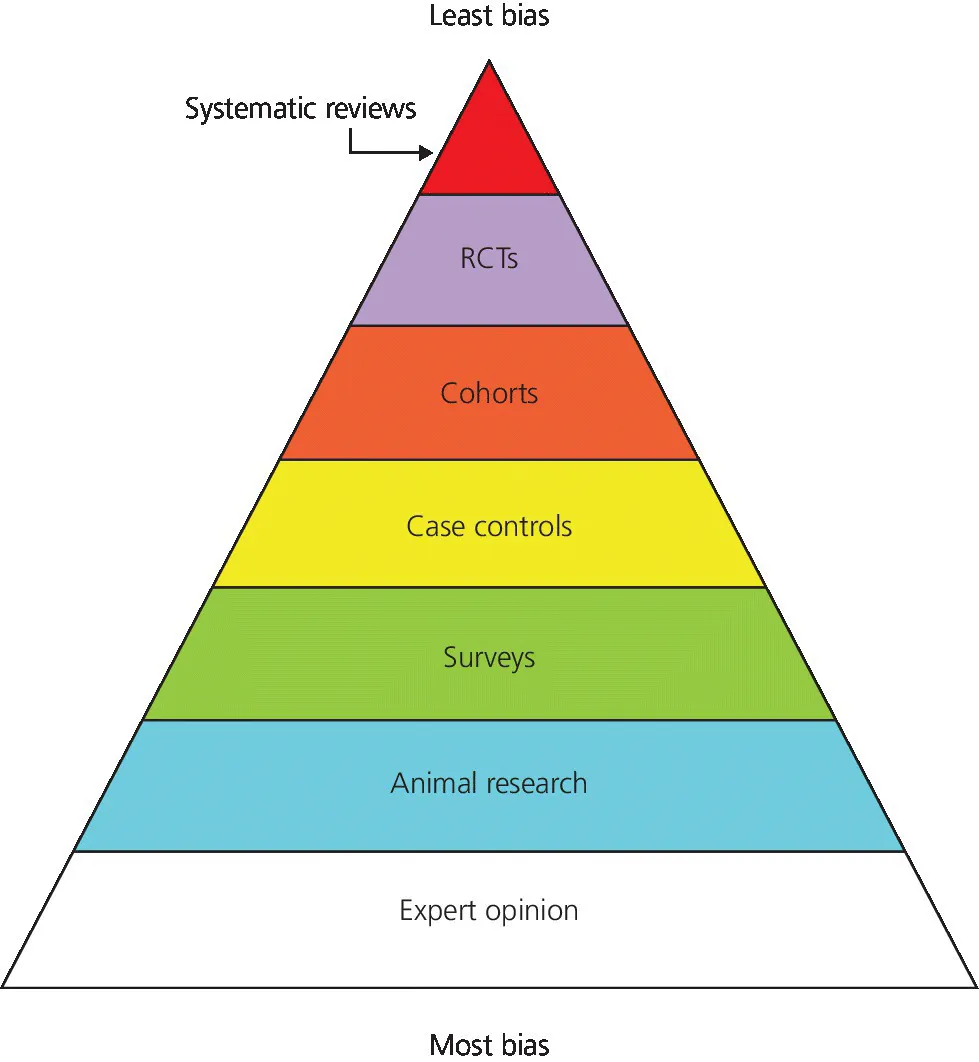

I could say, “Here is the hierarchy of evidence (Figure 1.1),” and save us, you the reader and me the author, a lot of time, but unfortunately things are not quite that simple. Routinely, if one is asked what the best evidence is, the response would be a meta‐analysis or systematic review and, not having that, a randomized controlled trial (RCT). What is also obvious from the figure is the categorization of animal and laboratory studies. While these present critical contributions to our basic knowledge and the background information needed to design clinical studies, they cannot and should not be utilized to make clinical decisions.

Figure 1.1 Hierarchy of evidence.

Source: Adapted from http://consumers.cochrane.org.

According to the Cochrane Collaboration,1 a Systematic Review (SR) “summarises the results of available carefully designed healthcare studies (controlled trials) and provides a high level of evidence on the effectiveness of healthcare interventions”; and a meta‐analysis (MA) is a SR where the authors pool numerical data. I want to bring your attention to the fact that nowhere in the definition does it mention, or limit itself to, RCTs. SRs and MAs are different from the more typical narrative review where an investigator evaluates all, or much, of the available literature and tenders an “expert opinion” of the results. They usually have loose or no inclusion and exclusion criteria and no “ranking” of the articles being reviewed. For those interested in how one categorizes articles, the following websites would be helpful:

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1891443/

- http://www.nature.com/ebd/journal/v10/n1/fig_tab/6400636f1.html#figure‐title

- http://www.ebnp.co.uk/The%20Hierarchy%20of%20Evidence.htm

We can break down studies into analytic or comparative, those that have a comparative group (randomized controlled trials, concurrent cohort studies, and case control studies) and descriptive, those that do not have a comparative group (cross‐sectional surveys, case series, and case reports). Descriptive studies give us useful information about a material, treatment, etc., however, to determine if one material, treatment, etc. is better than another, requires a comparative study.

In addition, studies may be prospective or retrospective. In a prospective study the investigator selects one or more groups (cohorts) and follows them forward in time. In a retrospective study the investigator selects one or more cohorts and looks backwards in time. Prospective studies are considered superior since they can ensure that the cohorts were similar for possible confounding variables at the beginning of the study, that all participants were treated equally, and that dropouts are known and accounted for. Prospective studies allow for randomization or prognostic stratification of the cohorts. Retrospective studies can be very valuable and should not be minimalized, especially in uncovering adverse outcomes that have a low prevalence or take many years to become evident. The adverse effects from smoking have mostly been uncovered by retrospective investigation.

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is a prospective, comparative study in which the assignment to the treatment or control group is done using a process analogous to flipping a coin. In reality, most projects are randomized utilizing a computer‐generated random assignment protocol. The sole advantage of randomization is that it eliminates allocation bias. Feinstein2 and Brunette3 feel that the universal dependence on RCTs to achieve this is overestimated and prefer prognostic stratification of the matched cohorts for major confounding variables prior to allocation. What soon becomes obvious, however, is that prognostic stratification is not possible for every potential confounding variable, so only “major” ones are usually accounted for.

Doing an RCT is ideal, but has the constraints of time (can we afford to wait the numerous years necessary to design, implement and publish?) and cost (where can you get the funding?). Furthermore, RCTs are only ideal for certain questions, for example one that involves therapy. If our question is one of harm, it would be unethical to randomize a patient to something with a known harmful effect. To my knowledge, there has never been a RCT that proved smoking was harmful. Could you get an Internal Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee approval to assign participants to a group that had to smoke two packs of cigarettes a day for 25 years? Yet, does anyone doubt, given the mass of clinical evidence, that it is better to not smoke? Ultimately, the design is determined by the question.

Sackett,4 considered by many to be the father of evidence‐based medicine, in response to the heated dialogue over which design was the best, and in an effort to refocus the time, intellect, energy, and effort being wasted, proposed that “the question being asked determines the appropriate research architecture, strategy, and tactics to be used – not tradition, authority, experts, paradigms, or schools of thought.”

Causation is one of the most difficult things to prove. It is like approaching a single set of railroad tracks. One can feel the warmth of the track and know that a train passed, but in which direction? It is why many studies conclude a “correlation.” In the EBM series authored by the McMaster faculty, the Causation section published in the Canadian Medical Journal had David Sackett using the pseudonym Prof. Kilgore Trout as the corresponding author.5 One can only wonder what motivated him to use the pseudonym rather than his own name to write on this critical topic. Sackett’s love of the works of Kurt Vonnegut is well known and one might wonder if, in fact, his Canadian home named the Trout Research & Education Centre, is based on Kilgore or the fish?

While the design is critical, one must also determine the validity of the methodology. According to Jacob and Carr,6 internal validity is a reflection of how the study was planned and carried out and is threatened by bias and random variation; while external validity defines if the results of the study will be applicable in other clinical settings.

Bias

There are many types of biases and a full explanation of the multitude reported is beyond the scope of this chapter. Still, there are a few that are meaningful to us as clinicians. We can divide bias into the following groups: the reader, the author, and the journal.

The reader

Taleb7 used the following quote to accent that past experience is not always the best method to judge what we are doing at the present time.

But in all my experience, I have never been in an accident…of any sort worth speaking about. I have seen but one vessel in distress in all my years at sea. I never saw a wreck and have never been wrecked nor was I ever in any predicament that threatened to end in disaster of any sort.E.J. Smith, 1907, Captain RMS Titanic.

The reader is almost always subject to confirmation bias, which is to believe whatever confirms one’s beliefs. It was best stated by Sir Francis Bacon8 : “The human understanding, once it has adopted an opinion, collects any instances that confirm it, and though the contrary instances may be more numerous and more weighty, it either does not notice them or rejects them, in order that this opinion will remain unshaken.” People seek out research in a manner that supports their beliefs. We have all invested time, energy, and money getting a dental education. We have successfully treated patients and are loath to admit that something we have been doing is not as useful, successful, good, etc., as another product, technique, or procedure. This is a form of cognitive dissonance and a common human reaction. It is difficult for a clinician, and especially an educator, to admit that what they have been doing and/or teaching is not currently the best for our patients. Remember, we performed the procedure with “older” information and materials and are evaluating our outcomes or planning new treatment with “newer” evidence. The best recourse is self‐reflection. Keeping up to date with clinically proven advances is our obligation as health providers.

The author

Allocation bias, a type of selection bias, is present when the two or more groups being compared are not similar, especially for confounding variables that could affect the outcome of the study. Familiar examples could be smoking, diabetes, osteoporosis, etc. Theoretically, randomization will account for this and is its major advantage, but only in the presence of a compelling number of participants (N).

The problem of allocation bias was demonstrated in a recent study.9 The investigators were attempting to compare a one‐stage protocol with a two‐stage protocol with respect to marginal bone loss after 5 years; unfortunately the patients in the two‐stage cohort were those who did not have a predetermined insertion torque at placement. As such, the two cohorts were not similar (one‐stage = high insertion torque, two‐stage = low insertion torque) for a major confounding variable and the internal validity of the study is in question.

Chronology bias refers to how long a clinical study ran and whether you, the reader, feel the time span was sufficient to justify the results and/or reveal expected or unexpected untoward responses. For example, company A has introduced a new implant surface that supposedly allows for faster osseointegration. How long would you expect the trial to run in order to accept the results as meaningful? What was their outcome assessment for success? Let's assume...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Prologue

- Acknowledgments

- About the Companion Website

- CHAPTER 1: The State of the Evidence in Implant Prosthodontics

- CHAPTER 2: Systemic Factors Influencing Dental Implant Therapy

- CHAPTER 3: Maintenance Considerations in Treatment Planning Implant Restorations

- CHAPTER 4: Three‐Dimensional Radiographic Imaging for Implant Positioning

- CHAPTER 5: Decision Making in Bone Augmentation to Optimize Dental Implant Therapy

- CHAPTER 6: Immediate Implant Placement and Provisionalization of Maxillary Anterior Single Implants

- CHAPTER 7: Surgical Complications in Implant Placement

- CHAPTER 8: Failure in Osseointegration

- CHAPTER 9: Implant Restoration of the Partially Edentulous Patient

- CHAPTER 10: Prosthodontic Considerations in the Implant Restoration of the Esthetic Zone

- CHAPTER 11: Ceramic Materials in Implant Dentistry

- CHAPTER 12: Cement‐Retained Implant Restorations: Problems and Solutions

- CHAPTER 13: Implant Restoration of the Growing Patient

- CHAPTER 14: Occlusion: The Role in Implant Prosthodontics

- CHAPTER 15: Evolving Technologies in Implant Prosthodontics

- CHAPTER 16: Implant Dentistry

- CHAPTER 17: Implant Restoration of the Maxillary Edentulous Patient

- CHAPTER 18: Implant Restoration of the Mandibular Edentulous Patient

- CHAPTER 19: Material Considerations in the Fabrication of Prostheses for Completely Edentulous Patients

- CHAPTER 20: Digital Alternatives in the Implant Restoration of the Edentulous Patient

- CHAPTER 21: Restoration of Acquired Oral Defects with Osseointegrated Implants

- CHAPTER 22: Implant‐Retained Restoration of the Craniofacial Patient

- CHAPTER 23: Peri‐Implant Diseases

- Epilogue

- Index

- End User License Agreement