![]()

Chapter 1

The Emergence of Emergence

Before embarking on a discussion of urban evolution, it is first necessary to define the notion of emergence specifically in relation to the nature of the city. Having explored this concept, this chapter will go on to relate my own experience of learning about urban complexity at first hand through active involvement in projects, which will lead on to reflections on the architect’s relationship with the complex city and the differentiation between design and planning.

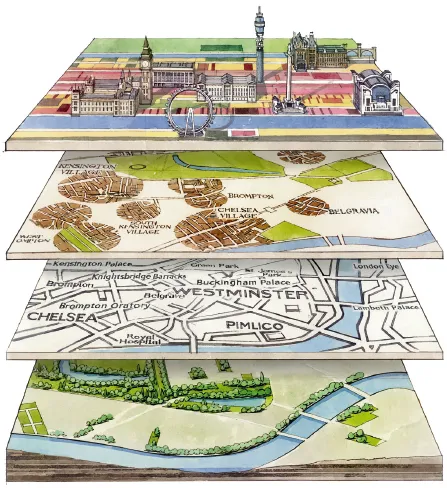

It seems self-evident that the city is produced by complex systems. Yet in the words of Evelyn Fox Keller, the microbiologist and pioneer of emergence theory: ‘It amazes me how difficult it is for people to think in terms of collective phenomenon [sic].’1 The notion of emergence – which Michael Weinstock describes in his book The Architecture of Emergence (2010) as requiring ‘the recognition of all the forms of the world not as singular and fixed bodies, but as complex energy and material systems that have a lifespan, exist as part of the environment of other active systems, and as one iteration of an endless series that proceeds by evolutionary development’2 – has only recently started to become widespread. Weinstock goes on to state that ‘causality is dynamic, comprised of multi-scaled patterns of self-organisation …. To study form is to study change.’3 This is as true of urbanism as it is of any other field.

Self-organisation as a subject for study and written texts has been predictably non-linear. It has roots in many crossover disciplines, including the economics of Adam Smith in the late 18th century, as well as the sociology of Friedrich Engels and the biology of Charles Darwin in the mid-19th century.4 These began to be unified with the powers of the computer, under the leadership of mathematicians such as Alan Turing in the mid-20th century. A recurring theme is the search for patterns in micro-behaviour that evolves, shifts and emerges as macro-behaviour. Darwin was a typical ‘searcher’ in this field of complexity, in that he immersed himself in his habitats and spent a lifetime observing like a detective – looking for patterns and orders. It is unsurprising that the new mathematics of Turing’s computer age returned to look at biology again, but with new eyes, new tools. Biomathematics emerged and remains at the forefront; but the lessons for all areas, including the city, soon became evident. The field of mycology led to ants, bees and on to human behaviour, our habitats and our interactions with them.

It was only then that the city became a selected subject for the study of emergence. Jane Jacobs is often credited with being the first (in any field) to use the term ‘organised complexity’ when, in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), she began what is widely considered to be the first rethink in the modern era of city planning. As she argued: ‘In parts of cities which are working well in some respects and badly in others … we cannot even analyse the virtues and faults … without going at them as problems of organised complexity.’5 In his 2001 book Emergence, Steven Johnson observed:

Traditional cities … are rarely built with any aim at all: they just happen. … organic cities … are more an imprint of collective behaviour than the work of master planners. They are the sum of thousands of local interactions: clustering, sharing, crowding, trading – all disparate activities that coalesce into the totality of urban living.6

Christopher Alexander also took up the idea of emergent forms of life: in his four-volume The Nature of Order (2003–4) he produced an overarching theory of a pattern of organisation, ranging from nature to city planning and architecture.7 Like many other books on the subject written in this period, his work is arguably too deterministic, undermined by a need to find new orthodoxies, new absolutes, a new order rather than the simpler acceptance of finding the order that is already there. Nevertheless, his astute observations of simple urban artefacts are a good way to begin. These already appeared in his earlier article ‘A City Is Not A Tree’ (1966), in which he describes a scene featuring a newsstand that is dependent on the adjacent set of traffic lights for its supply of customers: ‘the newsrack, the newspapers on it, the money going from people’s pockets to the dime slot, the people who stop at the light and read the papers, the electric impulses which make the traffic lights change and the sidewalk which the people stand on, form a system – they all work together’.8 Can the architect/planner rearrange or reinvent these physical things to make a more relevant order? Or does design follow, not lead? Jane Jacobs reserves her most withering observation of architectural vanity for Le Corbusier and his misplaced new ordering:

Le Corbusier’s dream city was like a wonderful mechanical toy, but as to how the city works, it tells … nothing but lies. … There is a quality even meaner than outright ugliness or disorder and this is the dishonest mask of the pretended order, achieved by ignoring or suppressing the real order that is struggling to exist and to be served.9

In the five decades since Jacobs’s book was published, professional bodies (institutes of planners, architects, surveyors etc), voluntary organisations (the US’s Institute for Urban Design and the UK’s Urban Design Group, both founded in the late 1970s as platforms for debate), multidisciplinary practices and university courses themselves have all endeavoured long and hard to get to grips with the overlapping professional and educational mindsets that are necessary to deal with the complexity of the city. It was in 1962, the year after Jacobs’s book came off the press, that I enrolled on the Masters in Architecture and City Planning programme at the University of Pennsylvania. The Penn course was, almost accidentally, unusually formative for me and the others in it, not because of what it did but rather the questions it asked of us – and therefore for what it did not do. Civic design or urban design, as it was later named, was presented as the course that had no answers. Right from the outset it gave us an unresolved professional world, an un-joined-up world of hybridity, which sat between several different disciplines. It plonked us in space rather than on a planet. Each of us had to take what we could from Ian McHarg on ecology, from Paul Davidoff on planning theory, from Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi on alternative ways of seeing art after the Modern movement, and of course there were Louis Kahn and Robert Le Ricolais, each in their architectural and engineering world.10 In the end it boiled down to those who dealt with the physical world and object-making and design, and those who dealt with law or politics who began by looking at the way people were and how they behaved, rather than trying to alter how they behaved through changes to the physical world. However, there were those who did try to make connections – Christopher Alexander at Berkeley, Kevin Lynch at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), David Crane at the University of Pennsylvania and others. They developed cross-connections and theories to try to make sense of the physical world and the personal world at the same time, bringing together the ordinary and the special.

Practice, Projects and Observing Complexity First Hand

The question of how to resolve the seemingly opposing aspects of professional specialisation and urban generalism has been with me all through my career. A single set-piece architectural scheme can have a far-reaching impact on its urban environment; the transformation of London’s Bankside Power Station into Tate Modern by Herzog & de Meuron (completed in the year 2000), for instance, was instrumental in the regeneration of a long-neglected section of the Thames riverfront. Observing and being involved in projects that have a degree of complexity, such as the architecture and planning of railway stations and airports, or indeed any large institution such as a university or hospital, can be hugely informative, often in many unexpected ways.

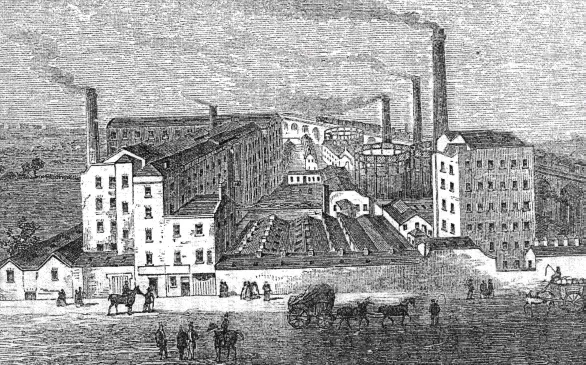

This is embodied in several masterplanning schemes our office undertook for the city of Manchester in 1998–2005, among which was Project Unity – a title that in itself explains a lot about ambition and purpose in physical city making. Manchester was the world’s first industrialised metropolis, but is also the city of Engels and my own family, who arrived from Ireland and were no doubt Engels’s contemporaries. Formed at an astonishing rate during the Industrial Revolution, it is a model for emerging new cities today not just in its phenomenal growth rate and semblance of civic greatness, but also for its rejuvenation in a much later post-industrial age: it has reinvented itself since the 1990s, reintegrating much that was of value from the past with the evolving contemporary condition. Urban complexity reaches a new level in this city. As Steven Marcus wrote in his book Engels, Manchester and the Working Classes, ‘It is indeed too huge and too complex a state of organised affairs ever to have been thought up in advance, to have preexisted as an idea.’11

Project Unity involved two universities that had once been joined, and had then been divided for social, political and cultural reasons in the 1960s, with one becoming a more technically orientated polytechnic and the other a more academic university. With changes in perception of how this was working or not working – and indeed there were many disadvantages to this artificial separation – it was decided to bring the two campuses back together again. The university and the polytechnic sat right within the city’s central core, surrounded by existing roads and railway stations, adjoining pubs and shopping centres and the central business district itself. At the time of the project, there was much enthusiasm for city making from the top down among the various actors on Manchester’s political stage.

To bring together two university campuses immediately raised questions on the nature of the faculties and departments, and on the differences between disciplines. The professors and heads of department would say, ‘My field is this’ and ‘Your field is that.’ It all exposed preconceived concepts of specialisation in buildings and occupants expressed in a physical campus where academia met reality. When comparing Manchester to, say, Oxford and Cambridge (and those educational institutions that have copied them), it is clear that the expressed reality on the ground of the Oxbridge campus, the physical focus, is a void. As Colin Rowe was to astutely observe in Collage City (1978), it is a space-positive planning concept.12 Around the Oxbridge void are gathered groups of buildings of mixed use where refectories, chape...