![]()

Chapter 1

The Contemporary Reinvention of Landscape Architecture and its Representation

We are witnessing a major break in the discipline of landscape architecture, stemming from a transformation in our understanding of nature. One of the characteristics of the contemporary view of nature is the acceptance that everything in it is constantly changing. This is the result of both the concept of evolution and that of emergence. While classical Darwinism assumed that all changes in living things take place gradually, Emergent evolutionists maintain that such events must be discontinuous. This shift in understanding means the end of most of the unacknowledged but deeply entrenched ways of working in landscape architecture and of representing landscape. For until recently, every design has had an implied end point, portrayed in a grand final rendering that harked back to a nostalgic paradise recovered in the design: a final, perfect image, fixed for all time. The scientific revolution of the 17th century viewed nature as rational and static – in fact, as the very foundation of the rationality to be pursued in organising human activities.

Beginning in the 19th century, a new understanding of a constantly changing nature slowly emerged. It was forged by people like Charles Darwin, who described the transformation of species over time (1859); Ernst Haeckel, the German marine biologist who first coined the term ecology and introduced the concept of an ecosystem in which humans and the rest of nature are bound together in a web of mutual interactions (1868); the French physiologist François Jacob, winner of the Nobel Prize in 1965, who saw human beings and the rest of the living world as a molecular bricolage in which old parts keep adapting to new functions; and the team of Herbert Bormann and Gene Likens (1974), who proved the existence of acid rain and the role of humans in creating this change in nature.1 Over the course of a century, these discoveries and paradigm shifts produced a cumulative picture of a nature in constant transformation. They changed not only our understanding of the natural world, but – very importantly – also our understanding of the interactions between humans and all other creatures, between living and inanimate forces of nature. This is a direct concern of landscape architecture.

We have all believed that the sea would be the sea forever, the perfect image of everlasting existence. But in the late 19th century, scientists began to demonstrate how supposedly eternal and immutable things are changing. They discovered that various species have evolved and then become extinct, continents have moved and continue to shift, seas and oceans have disappeared, and even the poles have changed location, following seemingly haphazard trajectories. They thought that such transformations happened very slowly, that no generation would witness them within its lifetime. But recent events have led many to think that such changes are more pervasive and more rapid than was ever anticipated.

Up to the Second World War, scientists modelled nature as a fixed, open thermodynamic system with established laws leading to optimal states of the biosphere. Even after the emergence of the field of ecology, the idea of an ever-changing nature did not become part of public discourse until the 1970s – and even then at first only professionals began to see things differently. This profound cultural change is ongoing.

Origins

An examination of the origins of landscape architecture and the two dramatic breaks in its history may help us to understand the field today. In its inception in the 17th century, when landscape architecture was first recognised as an activity with its own specialised knowledge, it was woven into the arts; painting, above all, can be called the art that generated the designed landscape. Poetry, theatre, sculpture and architecture were also considered part and parcel of it.

The landscape painting school, in particular French painters Claude Lorrain (1600–1682) and Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), presented landscape as something that had not been seen before the artist had looked upon it. WJT Mitchell has argued that landscape paintings produced the first unified picture of what before were separate unconnected objects, such as trees, rivers, roads, rocks and forests.2 That way of looking at our surroundings, which came to be called landscape, gave birth to the discipline of landscape design. What the painters saw for the first time made it possible for the landscapers to design what they saw, following the rules of composition of a landscape painting – for example, using background, middle ground and foreground. Those who eventually became identified as landscape designers had often been trained as painters, for example André Le Nôtre (1613–1700). Le Nôtre, the creator of Louis XIV’s gardens at Versailles, belongs to the first group of artists to be identified as landscape artists. The artistic view of the land dominated landscape painting until the early 20th century and landscape design well into the century.

Landscape progressed hand in hand with all the arts until the mid-19th century, when horticulture, botany, geology and scientific ideas began to take over the direction of the field, and its separation from the arts began. So total was this separation by the start of the 20th century, that when all the arts went through a major transformation together in 1911, landscape architecture was nowhere to be seen.3 It did not go through that revolution at all, and for most of the 20th century it was a minor discipline supporting architectural needs. It was not taught at the famous Bauhaus in Germany, which had been created as a school where all the arts were united and that became an expression of Modernism.

Yet in the mid-20th century, in Sweden and the United States – two countries fighting adverse economic circumstances – landscape architecture demonstrated its ability to confront major urban problems. In Sweden, it defended the environment as a public good. The Stockholm School of Landscape Architecture played an important role in the transformation of the city of Stockholm and its environment under the Social Democratic government, as in the case of Norr Mälarstrand linear park.4 In the United States, it played a major role in the development of parkways that followed the boom in automobile production. The suburban parkways of Westchester County, New York State (1913–38) gave form to this new landscape. The Bronx River Parkway and the Taconic Parkway, both in New York State, and the Merritt Parkway in Connecticut, are good extant examples.5 Landscape architecture also transformed a ruined river valley in Tennessee into a source of picturesque beauty and economic wealth.6 However, this success was short-lived; after the Second World War, in the United States it resumed a mostly decorative role until it shifted towards the field of ecology in the last third of the 20th century.

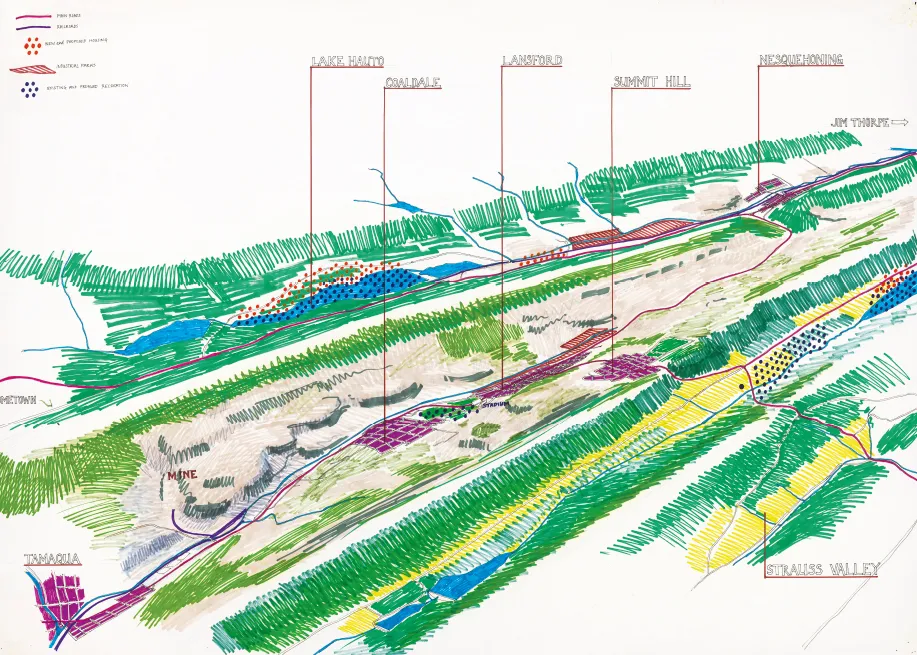

Through Ian McHarg’s book, Design with Nature (1969), landscape architecture made its mark as the earliest design profession to adopt an ecological perspective, and at times was even confused with ecology itself.7 Simultaneously, landscape architecture also began to engage with urbanism, partly through McHarg’s layered mapping analysis of cities and whole regions. In his drawings, McHarg gave an analysis of the different parts of a region which gave an overview of environmental concerns on a particular site.

These developments shed some light on the different associations that landscape design has had with different disciplines over time. In the 17th century, when landscape referred only to painting, the first terms used to differentiate the newly emerging field were landscape gardening and landscape design. By the late 19th century, it had become landscape architecture and was codified as such with the foundation of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) in 1899. Landscape ecology appeared in the 1980s, and now there is another reinterpretation of the discipline, with a new name, landscape urbanism. This history reveals the liminal character of the discipline, which allies itself with different fields at different times, taking on some of their perspectives and concerns but always continuing to exist as a distinct domain. It may now be time for the discipline to assume the word landscape by itself without any modifiers. It has ceased to mean painting, since you need to say landscape painting if that is what you mean, and it does not need to lean on any other discipline, though it does use in its work many different disciplines, but without any of them calling the tune.

Experiencing Change

Yet even in landscape ecology during the 1980s, nature was still considered static. One clear example of this is the concept of Clementsian succession, the idea of a stable path of a succession of species – for example, those of a forest – that climaxes in a biotic community in a state of equilibrium, where it then remains. Design with Nature and other works about ecology that followed still represented a belief that while nature can be disturbed, it is capable of returning to a steady state. This idea has been supplanted by concepts of non-equilibrium, which show that most natural ecosystems experience changes at a rate that makes a climax community unattainable. The newer Gleasonian succession model incorporates a greater role for random factors and denies the existence of sharply bounded communities. Today, any professional who believes that it is possible for any work to reach a final state is met with scepticism. But there is still a resistance, even among landscape designers, to seeing all nature as being in a state of transition. Some continue to want landscape design to produce nostalgic images of some lost harmony.

Others, however, may find the reality of constant change to be awe-inspiring. Numerous time-lapse Google Earth images show us 40 years of winters making whole sections of the Earth white with snow; no year is ever exactly the same as the one before, in spite of the cyclical nature of the seasons. Through Google Earth we can also witness the rapid and dramatic diminution of Central Asia’s Aral Sea over 40 years, half of it drying up completely. In this case we are seeing the effect of human agency as well, since diverting water from the Aral Sea to agricultural fields is the cause of this change to nature.

Landscape architects have responded in different ways to the understanding that nature is constantly changing, and have engaged in different issues of representation, as we shall see later in the book. Here, so the reader knows the point of view that informs my writing, I present my own response.

My first clear, conscious realisation of the role of change in my work occurred in 2005 during a project in St Louis on the Mississippi River. As I saw the river rising and falling, its level varying up to 40 feet (12 metres) in a year, and as I looked at a map that showed how the Mississippi had changed its course over hundreds of years, it began to seem absurd to try to contain such a mobile, ever-fluctuating element and fix it in place. At that time, I was reading John M Barry’s book, Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America.8 He describes how two clearly opposing visions of managing the river emerged in the late 19th century. The builder of the Eads Bridge in St Louis advocated using reservoirs and outlets – spillways – while the eventual head of the newly formed Army Corps of Engineers wanted to build levees. The Army Corps won, and a levees-only policy was established.

Spending time on that river, experiencing its enormous and continuous fluctuations, and learning about its history, gave rise to a deep sense of discomfort which I had felt before but which I couldn’t quite explain to myself. I saw that I was dealing with an extremely mobile, active, changing entity, and that there was a disconnect with the assumption that the way to treat it was to try to fix it in its course. By then, in every city with a river, there was a clear desire to have access to it. At the same time, it had also become evident that the typical treatment of rivers had be...