This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Education and Learning offers an accessible introduction to the most recent evidence-based research into teaching, learning, and our education system.

- Presents a wide range references for both seminal and contemporary research into learning and teaching

- Examines the evidence around topical issues such as the impact of Academies and Free Schools on student attainment and the strong international performance of other countries

- Looks at evidence-based differences in the attainment of students from different socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds, and explores the strong international performance of Finnish and East Asian students

- Provides accessible explanations of key studies that are supplemented with real-life case examples

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Education and Learning by Jane Mellanby, Katy Theobald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Education in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

What Can We Learn from the History of Education?

It is therefore the interest of all, that everyone, from birth, should be well educated, physically and mentally, that society may be improved in character, – that everyone should be beneficially employed, physically and mentally, that the greatest amount of wealth should be created, and knowledge attained.

Robert Owen (1771–1858), industrialist, promoter of the Co-operative movement, educator and philanthropist1)

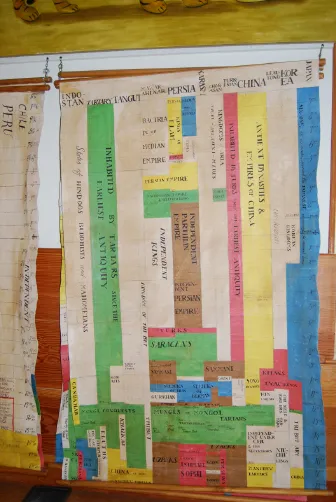

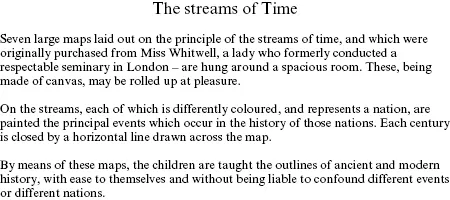

Do you agree? If you ever have the chance, visit New Lanark, a World Heritage Site on the River Clyde near Glasgow. This was Robert Owen's mill town where he implemented his educational ideas. Visitors can still see the lofty schoolroom, which was intended not only for the instruction of reading, writing and arithmetic but for the introduction of pupils to much wider knowledge. For example, the walls are still hung with charts of timelines of historical events in different countries all over the world (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). Owen's holistic approach included the workers' and their children's health and well-being: the children had a daily dance class before lessons (Figure 1.3) and he rebuilt family living quarters as relatively comfortable small apartments. Today we would regard his attitude as paternalistic, but I think we would also agree that his vision contains much to which contemporary education should aspire.

Figure 1.1 Hanging scrolls of timelines in the New Lanark schoolroom. Photograph by Susanna Blackshaw

Figure 1.2 Purpose of the timelines at New Lanark. Source: Extract from Robert Dale Owen's ‘Outline of the system of education at New Lanark’, 1824.

Figure 1.3 Children at New Lanark dancing before morning lessons. G. Hunt, 1825. Reproduced with permission from the New Lanark Trust; www.newlanark.org.

In modern Britain, an array of educational practices can be found in schools and universities, based on diverse and sometimes conflicting educational theories.

It is well worth taking an interest in the content and process of education, both in Britain and beyond, because the working of the education system affects everyone, whether as a learner, employer, teacher, parent or politician. It is evident that there are many views on the purpose of education and what a good education ought to entail. Some traditional views can seem old-fashioned, but in fact many apparently modern innovations only repeat what has been tried before, albeit under another name. After all, questions about the role, practice and purpose of education have been actively considered in advanced societies for more than 2,000 years.

A traditional view is that education is the reproduction and perpetuation of the culture of a society – as Jaeger,2 in his book Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture, has put it, how a community ‘preserves and transmits its physical and intellectual character’. A second perspective on the purpose of education emphasizes the need for the transmission of skills between the generations – reading, writing, arithmetic, playing musical instruments, painting and sculpture and more recently the use of IT (information technology). The literacy and numeracy hours in primary schools and training in PowerPoint or Access in secondary schools exemplify this trend. A rather different view of education is a political one – that it should provide a suitably qualified workforce. This was a view held in fourth-century bc Sparta where education was aimed at providing a well-trained army. Nor is such a view limited to the ancients. Thomas Sheridan (1756) wrote, ‘in every state it should be the fundamental maxim that the education of youth should be particularly formed and adapted to the nature and end of its government’. It was also a part of, but only a part of, Robert Owen's vision. Thatcher's government and those that followed have undoubtedly taken a similar stance. Indeed, today, when academics write applications for money to support their research they have to show that their work will not only add to existing knowledge or understanding, but will have ‘impact’ on society. It is important to be alert to, and even question, the views that policymakers and educators have regarding the nature and the role of education, because this has a great and often unacknowledged effect on what is taught, how it is taught and to whom.

Education for the reproduction of a culture

Why should a society wish to reproduce its own culture? And what role does education take in this? Culture encompasses a society's history, its social structure, its values and its creative achievements. Understanding our own culture is an important part of developing our own individual identity; seeing how we as an individual fit into a wider society. Once we have come to understand our culture, if we are comfortable with it and have chosen to embrace it, then it is human nature to seek to perpetuate it.

If we are looking at education as the reproduction of our culture, then a statement in a lecture3 by Nick Tate, a former Director of QCA (the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority), is particularly apposite: ‘education should give all children access to all those things that as a society we have decided we value and wish to pass on to our successors’. Such a view supports that of Thomas Arnold, the nineteenth-century educationalist: education should contain ‘the best that has been known and thought’. However, the problems here lie in the decision as to what is worth passing on to the next generations: who decides on the content of education? The National Curriculum (implemented in 1988, revised in 1995 and reviewed in 2007) was intended to encompass the corpus of knowledge that every educated person should be expected to possess, along with the basic skills of reading, writing and mathematics. Over the years, the curriculum became overloaded, as the proponents of many different subject areas fought to have their knowledge included. The 2007 review of the National Curriculum favoured reducing the factual content and proposed a radical change in the organization of knowledge – that is, the removal of subject boundaries. These boundaries have often been seen as supporting an elitist approach to learning, somehow following from the twentieth-century practice of subjects such as Latin being taught only in independent schools and grammar schools. However, in 2011 Michael Young4 forcefully argued against this: ‘Knowledge is not powerful just because it is defined by those who are powerful; it is powerful because it offers understanding to those who have access to it.’ The curriculum for all ‘should stipulate concepts associated with different subjects’ and enable pupils to ‘gain access to knowledge which takes them beyond their experience and their own preconceptions’.

A continual updating of curriculum content was supported in the 2007 review on the basis that this would ensure that pupils would see the curriculum as ‘relevant’ to them and to the society in which they lived. There has always been tension between views on the relative importance of ‘pure’ knowledge as opposed to applied knowledge in the classroom. The emphasis on ‘relevance’ can be traced to the work of John Dewey (1859–1952). He was an immensely wide thinker and a highly influential force in education. He believed that it was essential for education to be embedded in the ordinary life experience of the child at home and in the community – an emphasis on the applied aspects of knowledge. But the continual updating that is needed to maintain ‘relevance’ to contemporary life has caused considerable extra work and stress for the teaching profession. Tim Oates, who has chaired the most recent review determining the nature and content of the National Curriculum in primary schools, has taken a different point of view.5 He has pointed out that if the curriculum consists of core knowledge, such as the basic laws of physics and chemistry, then these will not change unless knowledge itself changes. Furthermore, he favours the division of knowledge into subjects since it can then be readily made coherent, so that one layer of knowledge follows another depending on the level of understanding of the developing child. Subjects rather than grandiose ‘themes’ are frameworks into which knowledge can be fitted – an essential aspect of the learning process. Oates has concluded that the curriculum should list the core knowledge, and that it should be left to the expertise of teachers to make the content relevant and motivating for the individual pupils. He has underlined the importance of looking to other countries that have successful education systems to try to learn from them, particularly in relation to the organization of the knowledge to be taught.

Treating education as a way to transmit our culture to a new generation makes sense in an insulated society where older and younger generations are broadly alike. But what about a multicultural society with much immigration of people from other cultures? The production of ‘community cohesion’ in a successful multicultural society requires many people to acquire two (or more) such individual identities – that of the adopted culture and that of the culture of origin. Where these conflict, for example in the role of women in society, this can lead to problems. Education then goes beyond reproduction of culture. Instead it takes on an important role in encouraging both coexistence and assimilation through the acquisition of knowledge and understanding of different cultures.

Lessons from History

At a time when education is so much in the public eye, it is worth considering what we might learn from education systems of the past. We can try to understand the value (and constraints) of the methods of teaching employed: how to teach reading, for example; the role of rote-learning; or the importance of memory versus documentation. It is interesting to recognize how the content and structure of past systems map onto the contemporary National Curriculum. And, most importantly, we can seek out common factors in different ‘successful’ systems that might be applied today.

Education in Ancient Greece

The origins of our traditional attitudes to education lie in the work of philosophers in fifth- and fourth-century bc Greece. The Greek philosophers conceived the conscious idea of culture and created a self-consciousness about the educational process in which they gave consideration to what the nature and intention of education should be. They devoted much thought to the idea of a standard, an ideal person and an ideal community. We must remember that we are not really any different from the inhabitants of Ancient Greece: they were at least as intelligent as we are and their brains at birth would have been similar to the brains of our babies, following the same developmental trajectories, although also being moulded by specific experiences which would have had similarities to, and differences from, our own. So, if we can understand what worked for the Greeks, then that might well work for us too.

Even in ancient Athens, the tension we see today existed between the belief that education should involve teaching facts and the belief that it should prepare the mind for future action. The trivium (three parts), grammar, rhetoric and dialectic, formed the central part of education. Grammar involved the full understanding of the structure of the language. Nowadays, the explicit teaching of English grammar is not often undertaken in English schools, but it was an integral part of the grammar school curriculum 50 years ago and the teaching of native grammar is still given time in the curriculum of many modern European systems, including those of France, the Netherlands and Germany. We do not know how much explicit teaching of grammar helps us to express ourselves, but the correct use of complex grammar does allow one to communicate subtleties that tend to be lost when language is simplified.

Rhetoric involved the processes leading up to the presentation of a reasoned argument. Firstly, the student would need to accumulate the relevant knowledge; then this knowledge would need to be organized; then, since rhetoric involved oral presentation, the style of delivery needed to be considered; then the speech would need to be committed to memory; and finally it would have to be delivered to the relevant audience. Rhetoric involved a combination, therefore, of acquiring knowledge and of the ‘transferable skill’ of presentation.

Dialectic involved the search for truth through a dialogue between teacher and student. Even today, in a classroom with many pupils, we see teachers using a similar approach in asking questions and steering discussion.

By the middle of the first century bc, the intellectual gymnastics of rhetoric and dialectic had been afforced by the more fact-based quadrivium (four parts), arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy, to form the seven liberal arts curriculum. It is clear that there is much in common between the current National Curriculum and the seven liberal arts: the importance of language, the importance of the transferable skill of oral delivery, the importance of mathematics and science (although admittedly astronomy, being largely astrology at that time, would not now be considered a science). Indeed, Michael Gove's proposed ‘English Baccalaureate’ is even closer to the seven liberal arts formula.

One obvious difference between the National Curriculum and education in fourth-century Athens is the integral part played by music and physical exercise in the past compared with the peripheral role that it now has in British schools. Music, poetry, dance and gymnastics were all deemed to be very important, and indeed even used to teach moral values. It is interesting that there is now scientific evidence that physical exercise both improves intellectual function and helps to preserve that function during ageing, and that this is supported by evidence concerning the underlying physiological mechanisms (Chapter 2). This valuing of physical movement, therefore, which at the time was based o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Introduction: What Can We Learn from the History of Education?

- Chapter 2: Memory: How Do We Remember What We Learn?

- Chapter 3: Language: What Determines Our Acquisition of First and Second Languages?

- Chapter 4: Reading: How Do We Learn to Read and Why Is It Sometimes so Difficult?

- Chapter 5: Intelligence and Ability: How Does Our Understanding of These Affect How We Teach?

- Chapter 6: Sex Differences: Do They Matter in Education?

- Chapter 7: Metacognition: Can We Teach People How to Learn?

- Chapter 8: Academic Selection: Do We Need to Do It and Can We Make It Fair?

- Chapter 9: Creativity: What Is It, and How and Why Should We Nurture It?

- Chapter 10: Education Policy: How Evidence Based Is It?

- Chapter 11: Comparative Education: What Lessons Can We Learn from Other Countries?

- Chapter 12: Life-long Learning: How Can We Teach Old Dogs New Tricks?

- Chapter 13: Technology: How Is It Shaping a Modern Education and Is It Also Shaping Young Minds?

- Chapter 14: Conclusions: What Does the Future Hold for Education?

- Index