This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

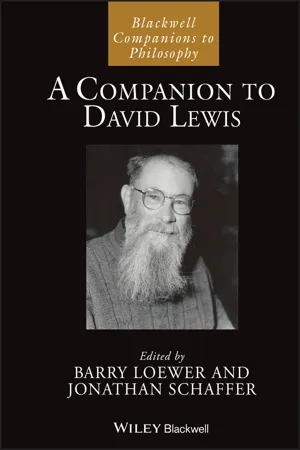

A Companion to David Lewis

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In A Companion to David Lewis, Barry Loewer and Jonathan Schaffer bring together top philosophers to explain, discuss, and critically extend Lewis's seminal work in original ways. Students and scholars will discover the underlying themes and complex interconnections woven through the diverse range of his work in metaphysics, philosophy of language, logic, epistemology, philosophy of science, philosophy of mind, ethics, and aesthetics.

- The first and only comprehensive study of the work of David Lewis, one of the most systematic and influential philosophers of the latter half of the 20th century

- Contributions shed light on the underlying themes and complex interconnections woven through Lewis's work across his enormous range of influence, including metaphysics, language, logic, epistemology, science, mind, ethics, and aesthetics

- Outstanding Lewis scholars and leading philosophers working in the fields Lewis influenced explain, discuss, and critically extend Lewis's work in original ways

- An essential resource for students and researchers across analytic philosophy that covers the major themes of Lewis's work

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Companion to David Lewis by Barry Loewer, Jonathan Schaffer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Biography and New Work

1

Intellectual Biography of David Lewis (1941–2001)

Early Influences

This chapter is not a cradle-to-grave intellectual biography of David Lewis. In particular, it does not try to be comprehensive about the origins of his views or of how he came to hold them. Its purpose is to exhibit elements of the origins of the David Lewis we knew, philosopher and human being, and whose works we know. It describes important influences on David as a child, as an adolescent, and as a young man.

Let me begin with the last, and most important, of the forces that shaped the adult David, and made him the philosopher that he was. Not the only influence: nothing would have made David into the philosopher he was if he didn't have the wherewithal to begin with.

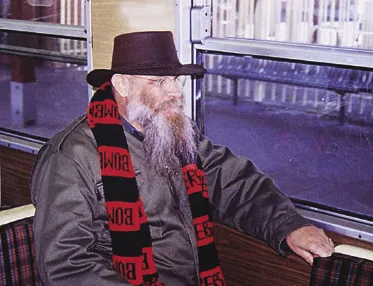

David, and usually I as well, made many visits to Australia: in 1971, in 1976, and nearly every year (except 2000, the year of David's kidney transplant) from 1979 right through 2001. He gave talks, went to talks, conversed with many people, and whenever he was in the right place at the right time he attended the Australasian Association of Philosophy conference. We toured around and enjoyed the urban amenities of Melbourne and, to a lesser extent, Sydney. And, starting in 1980, we went to the footy (Figure 1.1). David, who in general had no interest whatever in sport, somehow became a one-eyed supporter of the Essendon Football Club, in the Victorian (subsequently, the Australian) Football League. He was buried with his Essendon membership card in his pocket.

In July of 2002, nearly a year after David's death, I visited Australia by myself, and attended the Australasian Association of Philosophy conference. At the conference dinner, someone rose and asked us all to take a moment to remember David. After a minute or so, they shoved the microphone at me and asked me to say something. My only preparation for this was three glasses of wine. The first words that came out of my mouth were “Australia made David.” I must have said more, but I have no recollection at all of what it might have been.

1.1 Childhood

David was born into an academic household in Oberlin, Ohio, on September 28, 1941. He was the eldest of three children. His father, John D. Lewis, was professor of government at Oberlin College, where he taught from 1936 until his retirement in 1972. John was one of the great Oberlin teachers of his time, an Oberlin oligarch. As student and faculty member, he was at Oberlin for 41 years. John hadn't much standing as a scholar or researcher, especially in the later part of his career; his mark was on his generations of students, including Cecilia Kenyon, Kenneth N. Waltz, Sheldon Wolin, and W. Carey McWilliams Jr. Many others in other careers expressed their gratitude for his intellectual influence on them.

David's mother, Ewart Kellogg Lewis, was the scholar, by inclination, anyway. Unlike her husband, she came from an academic family. She was a graduate of the University of Wisconsin, also Phi Beta Kappa, having fled Wellesley College, and she held the PhD from the University of Wisconsin. She published Medieval Political Ideas (1954), a collection of critical translations and introductory essays of medieval philosophers and political theorists. She published no other scholarly works that I can find. Her reputation in medieval political theory survives.

She had no formal teaching career to speak of. Oberlin had, or was thought to have, a nepotism rule, so, other than casual employment in the history department, a post at Oberlin College was denied her. Neither she nor her husband was inclined to challenge this and, in any case, her employment at Oberlin ended after a squabble over the appointment of another faculty spouse. She did have an instructorship at Western Reserve University in Cleveland for three years.

She was an academic to the core, even though running the household fell to her. She taught her children to read early, and strongly encouraged David's native bookishness. When David was nine or ten years old he had an attack of polio, and, unrelated to this, a bone cyst in his thigh was discovered. He had a transplant of bone chips to cure the cyst, and as a consequence spent several weeks in, or mostly in, bed. Ewart taught him Latin. (He also took Latin in high school.) She also taught him to type properly.

David, born of two Phi Beta Kappa academics, was the eldest of three siblings. Being the eldest, and a little ungovernable, and being recognized from an early age as someone with intellectual curiosity and motivation, he was allowed to follow his own inclinations about his studies and activities.

The portion of this chapter dealing with David's childhood and early adolescence draws partly on Lewis family myth and folklore, but primarily on an autobiography he wrote, at the age of 14, in his next-to-last year of high school. It doesn't show much introspection: it has a lot of facts and family history in it. But it does describe his interests at various times. He, like most smart kids, read a lot and was interested in science. The autobiography has next to nothing in it about school friends, and most of the stories of family interactions are about his father. He was a solitary boy, planning and doing projects by himself, and reading. From what he says about various science projects his attention span appeared, even as a small child, to be unbounded. He wasn't unsocial but, if the autobiography is accurate, most of his interactions were with adults. There is only one mention of a friend of his own age.

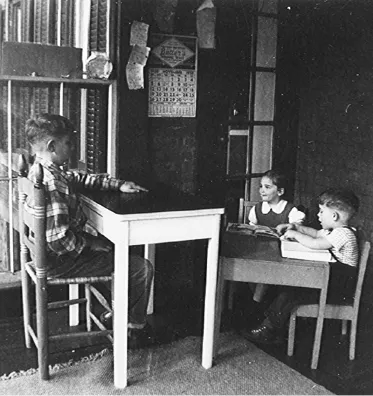

It isn't as if David didn't care for his siblings, nor they for him. There is a photo of David from 1950, when he was nine years old, sitting in his father's study at their house, teaching school to his brother Donald, then five years old, and his sister Ellen, then three. They are listening raptly, their books open before them. The posture of David explaining something to an attentive audience will strike anybody who knew him as familiar (Figure 1.2).

For all practical purposes, David barely went to high school. Between the fall of 1954 and June of 1957, his high school years, he attended several courses at Oberlin, General Chemistry and Organic Chemistry among them, and took the exams and did the lab work. He had a chemistry lab in the basement of the Lewis house, where he did chemistry experiments and glassblowing. (And no, he never did nearly blow up the house.) One summer he worked on a project in a college lab, supervised by Professor Renfrow, in the Oberlin chemistry department. David Sanford remembers him from Oberlin chemistry classes as smarter and better prepared than any of the other students.1

David also showed early signs of the highmindedness that characterized him for his entire life. In a draft of his essay to accompany his application to Swarthmore College, written in the spring of 1957, he says:2

Last spring [of 1956], when a high school teacher was fired without reasons given, I was one of five students who drew up and circulated a petition asking the [Oberlin] Board of Education to give reasons. This petition, signed by about 60% of the High School students, was followed by a series of petitions and protests by teachers and citizens which finally resulted in a thorough investigation of the school situation by the Board of Education, and the replacement of the Superintendent of Schools by a new man who is initiating several much-needed reforms, I got very much interested in the whole situation and have been attending School board meetings regularly since then.

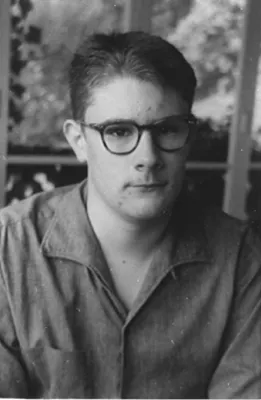

In the course of high school, his interests evolved and he continued to grow into the David we knew. Here is the last section of that autobiography: he was 14 when he wrote it, in 1955 [Figure 1.3], and there is no evidence whatever of ghostwriting (Ewart did type it) by either his mother or his father. David is uncharacteristically pompous, but the voice is his own.

LOOKING AHEAD

This, then, is the story up to now. But it is still incomplete. After all, one's first fourteen years are not the greater part of life; it is necessary to say something about the future. Moreover, this has been a record primarily of events: I have not yet said much about what I think of it all. And these are important; for an event is almost meaningless, as I see it, in comparison with an idea.

To take first the matter of concrete plans for the future, I must begin by saying that I am not sure of any of it. I expect to finish high school in the next year, taking, perhaps, some courses at Oberlin College also. After that, I intend to enter some college; I do not know where. I would like to go to a serious college, preferably a small...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Table of Contents

- Blackwell Companions to Philosophy

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Notes on Contributors

- Part I: Biography and New Work

- Part II: Methodology and Context

- Part III: Metaphysics and Science

- Part IV: Language and Logic

- Part V: Epistemology and Mind

- Part VI: Ethics and Politics

- Bibliography of the Work of David Lewis

- Index

- End User License Agreement