![]()

PART ONE

Theoretical and Practical Background

![]()

chapter ONE

Transformation and Renewal in Higher Education

As teachers, we guide and support our students to become independent thinkers. We endeavor to teach the whole person, with an intention to go beyond the mere transfer of facts and theories. The advent of online learning and the availability of information on the Internet have made our focus on deeper and richer experiences of teaching and learning ever more important. While concentrating on these holistic goals, we also want to challenge and develop students' analytical problem-solving skills as well as provide careful explanations of complicated material. We want to create the opportunity for our students to engage with material so that they recognize and apply its relevance to their own lives, to feel deeply and experience themselves within their education. In other words, while fostering their knowledge base and analytical abilities, we want to present material in a way that supports students in having their own agency so that the material is not simply a set of intellectual hoops for them to jump through but an active opportunity for them to find meaning and develop intellectually.

This is no easy task. Focusing on our students' agency does not mean that our courses should or even could be equal collaborations. Negotiating this divide carefully—on the one hand, wanting to engage with students rather than talk at them, while on the other, knowing that we remain their teachers (however we conceive of that)—is a difficult but worthwhile process. In traversing these two poles, we often err on the side of rigid structure, and we stress the abstract and conceptual.

But concentration on outcomes, abstraction, and narrow information handling has its costs. In her book Mindfulness, Ellen Langer writes that perhaps one of the reasons that we become “mindless” is the form of our early education. “From kindergarten on,” she writes, “the focus of schooling is usually on goals rather than the process by which they are achieved. This single-minded pursuit of one outcome or another, from tying shoelaces to getting into college, makes it difficult to have a mindful attitude toward life. Questions of ‘Can I?’ or ‘What if I can't do it?’ are likely to predominate, creating an anxious preoccupation with success or failure rather than drawing on the child's natural, exuberant desire to explore” (Langer, 1989, pp. 33–34). Indeed, the history of educational reform is full of examples of the responses to the heavy costs of this sort of concentration. It is this sense of deep exploration and inquiry that has led us to develop a pedagogy that uses contemplative methods.

We have often stressed the highly instrumental form of learning to the exclusion of personal reflection and integration. It is understandable how this happens; developing careful discursive, analytical thought is one of the hallmarks of a good education. However, creative, synthetic thinking requires more than this; it requires a holistic engagement and attention that is especially fostered by the student finding himself or herself in the material. No matter how radically we conceive of our role in teaching, the one aspect of students' learning for which they are unambiguously sovereign is the awareness of their experience and their own thoughts, beliefs, and reactions to the material covered in the course. In addition, students need support in discerning what is most meaningful to them—both their direction overall and their moral compass. Without opportunities to inquire deeply, all they can do is proceed along paths already laid down for them.

Researchers and educators have pursued the objective of creating learning environments that are deeply focused on the relationship of students to what they are learning as well as to the rest of the world. We have found that contemplative practices respond powerfully to these challenges and can provide an environment that supports the increasing diversity of our students. While contemplative practices vary greatly, they all have the potential to integrate students' own rich experience into their learning. When students engage in these introspective exercises, they discover their internal relationship to the material in their courses.

To be sure, others have thought about expansive and reflective approaches to teaching. For example, the famous work of John Dewey and Jean Piaget and the radical reframing of education by Paolo Freire all have experiential components at the heart of their systems (Dewey, 1986; Piaget, 1973; Freire, 1970). Dewey, in particular, has keen insights on the relationship between experience and reflection. (See, for example, Rodgers, 2002.) In fact, entire educational systems have been built around experience. For example, the experiential learning theory system of Daniel Kolb posits two sets of related inquiries: concrete experience and abstract conceptualization on the one hand and reflective observation and active experimentation on the other. Indeed, the advocates of the integrative education movement, influenced by the systems of thinkers like Ken Wilbur and Sri Aurobindo, call for the active attention on combining domains of experience and knowing into learning (see, for example, Awbrey, 2006). Thus, our focus on contemplative and introspective practices is not unknown in academia; what distinguishes the experience and integration discussed in this book is that the experience is focused on students' introspection and their cultivation of awareness of themselves and their relationship to others. The exercises are relatively simple and mainly conducted in their own minds and bodies, relating directly to their personal experience discovered through attention and awareness, yet these private investigations yield increased empathy for others and a deeper sense of connection with the world (Birnie, Speca, & Carlson, 2010).

Contemplation, Introspection, and Reflection

In this book, we will be talking about contemplative practices and pedagogy, sometimes using introspection, reflection, or other terms interchangeably. Although the range of these practices is very broad, all of them have an introspective, internal focus. Whether they are analytical exercises asking students to examine a concept deeply or opportunities to simply attend to what is arising, the practices all have an inward or first-person focus that creates opportunities for greater connection and insight. Although students might be silent or speaking, still or in motion, the practices all focus on the present experience, either physical or mental. The practices certainly include meditation, but not all are meditative in the traditional sense. They range from carefully beholding chemical mappings and making observations, to sitting in stillness, to imagining the impacts of distributing different proportions of goods to loved ones and to strangers. They include both simple and complex concentration practices that sometimes require periods of calm and quiet and sometimes sustained analytical thinking. The critical aspect is that students discover their own internal reactions without having to adopt any ideology or specific belief. They all place the student in the center of his or her learning so that the student can connect his or her inner world to the outer world. Through this connection, teaching and learning is transformed into something personally meaningful yet connected to the world.

We recognize that the idea of a first-person focus has complex ontological and epistemological implications. In essays like Hans-Georg Gadamer's “On the Problem of Self-Understanding” (1976) and Evan Thompson's “Empathy and Consciousness” (2001) the metacognition necessary for evaluative self-awareness is examined and evaluated. While these inquiries are fascinating and important in considering the nature of awareness, self-conception, and knowing, we will not consider them here. Here we are stimulating the inquiry.

Responding to the Call

By legitimizing students' experience, we change their relationship to the material being covered. In much of formal education, students are actively dissuaded from finding themselves in what they are studying; all too often, students nervously ask whether they may use “I” in their papers. A direct inquiry brought about through contemplative introspection validates and deepens their understanding of both themselves and the material covered. In this way, they not only understand the material more richly but also retain their knowledge better once they have a personal context in which to frame it. Questions about how the material fits “into the real world” or is in some way relevant to their lives don't arise. The presentation of the material is approached in a manner in which students themselves directly discover its impact on their lives. Since they are conducting the inquiry with their classmates, they also realize their connection with each other, without any forced discussion of relatedness. This process builds capacity, deepens understanding, generates compassion, and initiates an inquiry into their human nature.

Remarkably these exercises can be used effectively throughout the curriculum: in sciences like physics, chemistry, and neuroscience; in social sciences, like sociology, economics, history, and psychology; in humanities such as art history, English, and philosophy; and in professional schools, including nursing, social work, architecture, business, law, and medicine. Their exact use changes from discipline to discipline, but as we shall see, the diverse practices are deeply connected.

The form and function of education are greatly influenced by the policy goals that underlie its purpose. Most higher education institutions are nonprofit enterprises and are highly subsidized, including financial aid to students. Even students who pay the full tuition and fees are being subsidized since fees are well below per-student average costs. In fact, one of the ways of thinking about alumni gifts to the institution is a repayment of the subsidies they received as students (Winston, 1999). Since these institutions are not focused on profit, they must be able to justify the subsidies and the appeals for charitable contributions in other ways. Some schools have religious orientations, which provide their vision and purpose, but the visions and aspirations of secular schools come from a sense of the common good that they are supporting. As teachers in these institutions, we consider our intentions for each course we teach, but we rarely step back and inquire about our overall vision of the education we are providing. With the pressure of ever increasing costs, the viability of higher education depends on our ability to articulate these aspirations. Contemplative exercises provide a means to engage in this inquiry.

In recent years, a steady stream of books has been published about the crisis in higher education and how colleges and universities are failing to educate students. It is argued again and again that we have failed to provide needed skills and have lost sight of our true calling. In Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses (2010), Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa claim that nearly half of college students demonstrated no significant improvement in a range of skills—critical thinking, complex reasoning, writing, and so on—after the first two years of college. While colleges and universities have been attacked on the provision of skills, they have been criticized even more harshly for not providing students with a vision of how their studies might affect society at large. In Crisis on Campus: A Bold Plan for Reforming Our Colleges and Universities (2010), Mark Taylor argues that “the curriculum [has] become increasingly fragmented, and the educational process loses its coherence as well as relevance for the broader society” (p. 4). In an especially damning critique, Harry Lewis, former dean of Harvard College, writes, “Universities have forgotten their larger educational role for college students. They succeed, better than ever, as creators and repositories of knowledge. But they have forgotten that the fundamental job of undergraduate education is to … help [students] grow up, to learn who they are, to search for a larger purpose for their lives, and to leave college better human beings” (2006, p. xii).

We believe that it is not too late to address these problems. In fact, contemplative modes of instruction provide the opportunity for students to develop insight and creativity, hone their concentration skills, and deeply inquire about what means the most to them. These practices naturally deepen understanding while increasing connection and community within higher education. We believe that at its core, the academy must provide students with the opportunity to initiate and pursue an inquiry into their role in society, an inquiry that makes learning personal, meaningful, and relevant. Like John Dewey, social reformers and education theorists began thinking of education as the means to promote personal agency and economic opportunity. Dewey began to see that schools functioned powerfully in “prevailing structures of power.” Contemplative practices place the students at the center of their own learning, shifting the balance of power in the classroom in a meaningful and engaged manner.

These practices also directly address essential learning protocols. In How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching, Susan A. Ambrose, Michael Bridges, Michele DiPietro, Marsha Lovett, and Marie Norman (2010) evaluate the latest research on effective teaching. Many of the key findings relate directly to contemplative practices. Among their many strategies to improve teaching and learning, they advocate the importance of holistic student development and emotional regulation, the advantages of self-awareness and self-monitoring, and the central role of metacognition (personal reflective activity). Not only is emotional and social learning fundamental to student productivity, this type of learning during the college years is actually considerably greater than intellectual gains. As we shall see in the next chapter, contemplative practices support and sustain emotional regulation by allowing students to recognize triggers and be less reactive. This increases learning outcomes in the short run and produces better-balanced citizens in the long run. Contemplative practices are self-reflective practices; they support and sustain the types of self-monitoring activities that research has found crucial for student development and learning. Studies have shown that students who monitor their progress and explain to themselves what they are learning have greater learning gains and were better problem solvers than those who do not (Ambrose et al., 2010). In addition, without practice, we have a tendency to overestimate our abilities, making it less likely that students needing remedial attention will seek it. Finally, both learning and teaching requires sitting back and surveying the big picture, making sure that our strategies are achieving course-level goals and providing students broad gains for their development within and beyond the course (Ambrose et al., 2010).

Beyond these gains, contemplative practices can be designed to focus on various types of learning. For example, the practices can be visual, auditory, cognitive, or physical. While it is true that students might favor one mode over another (say, visual explanations rather than verbal ones), the evidence seems mixed about how much benefit is attained from presentations solely geared to styles associated with certain students. Researchers led by Rita Dunn and Kenneth Dunn at St. Joseph's University reported significant gains from tailoring teaching to learning style preferences. This certainly has captured the imagination of teachers and schools of education and does make intuitive sense. However, Kenneth A. Kavale, Steven R. Forness, and others have shown that the results do not seem statistically robust and that whatever gains exist result simply from the extra attention placed on personal instruction—efforts that when placed elsewhere might have similar effects (Kavale & Forness, 1987).

While the overall benefits from learning style–based teaching are somewhat controversial, there is a broader consensus on adjusting presentation to the content. Certain topics lend themselves rather naturally to types of presentation: for example, visual information like form and color is probably best conveyed with visual examples, while if you were teaching about how honeybees communicate the location of nectar-filled flowers, you might incorporate movement to help students understand the “honey bee dance language” and how it differs from explanations based on odor.

Introspective and Contemplative Practices

Contemplative pedagogy uses forms of introspection and reflection that allow students to focus internally and find more of themselves in their courses. The types of contemplation are varied, from guided introspective exercises to open-ended, multistaged contemplative reading (i.e., lectio divina) to simple moments of quiet, as are the ways in which the practices are integrated into classrooms. What unites them is a focus on personal awareness, leading to insight.

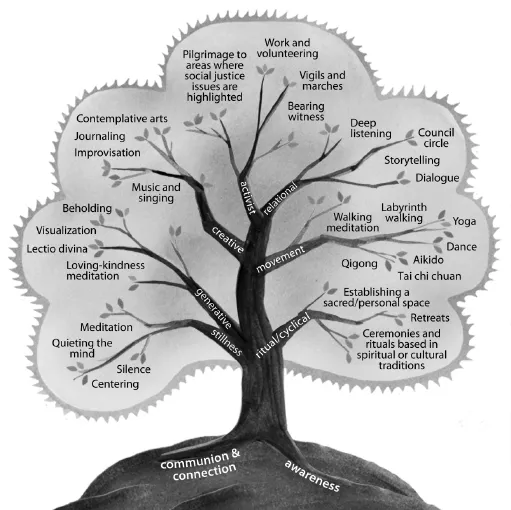

As an introduction, the tree of contemplative practices (figure 1.1) created by the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society illustrates the diversity of practices. This is not an exhaustive summary but does give an excellent overview of the basic categories and the practices within each.

Practices from different categories can also be combined; for example, meditation can be combined with freewriting or journaling, or a movement exercise can be combined with activist activities. The exact form of the practices depends on the context, the intent, and the skills of the facilitator.

These practices, which can take many forms, are highly adaptable to different contexts throughout the curriculum. In March 2011, Amherst College and the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society hosted a conference in which practitioners from physics,...