eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Solitude

Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation, Social Withdrawal, and Being Alone

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Handbook of Solitude

Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation, Social Withdrawal, and Being Alone

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This reference work offers a comprehensive compilation of current psychological research related to the construct of solitude

- Explores numerous psychological perspectives on solitude, including those from developmental, neuropsychological, social, personality, and clinical psychology

- Examines different developmental periods across the lifespan, and across a broad range of contexts, including natural environments, college campuses, relationships, meditation, and cyberspace

- Includes contributions from the leading international experts in the field

- Covers concepts and theoretical approaches, empirical research, as well as clinical applications

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Handbook of Solitude by Robert J. Coplan, Julie C. Bowker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Psicología del desarrollo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Theoretical Perspectives

1

All Alone

Multiple Perspectives on the Study of Solitude

Seems I’m not alone in being alone. – Gordon Matthew Sumner (1979)

The experience of solitude is a ubiquitous phenomenon. Historically, solitude has been considered both a boon and a curse, with artists, poets, musicians, and philosophers both lauding and lamenting being alone. Over the course of the lifespan, humans experience solitude for many different reasons and subjectively respond to solitude with a wide range of reactions and consequences. Some people may retreat to solitude as a respite from the stresses of life, for quiet contemplation, to foster creative impulses, or to commune with nature. Others may suffer the pain and loneliness of social isolation, withdrawing or being forcefully excluded from social interactions. Indeed, we all have and will experience different types of solitude in our lives.

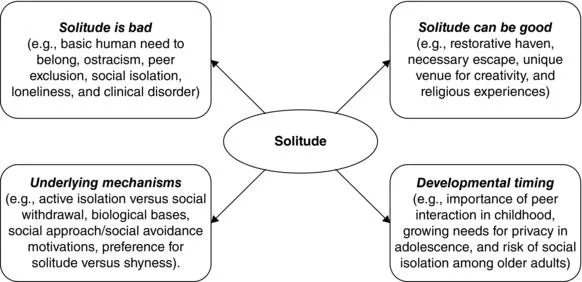

The complex relationship we have with solitude and its multifaceted nature is reflected in our everyday language and culture. We can be alone in a crowd, alone with nature, or alone with our thoughts. Solitude can be differentially characterized along the full range of a continuum from a form of punishment (e.g., time-outs for children, solitary confinement for prisoners) to a less than ideal context (e.g., no man is an island, one is the loneliest number, misery loves company), all the way to a desirable state (e.g., taking time for oneself, needing your space or alone time). In this Handbook, we explore the many different faces of solitude, from perspectives inside and outside of psychology. In this introductory chapter, we consider some emergent themes in the historical study of solitude (see Figure 1.1) – and provide an overview of the contents of this volume.

Figure 1.1 Emergent themes in the psychological study of solitude.

Emergent Themes

The study of solitude cuts across virtually all psychology subdisciplines and has been explored from multiple and diverse theoretical perspectives across the lifespan. Accordingly, it is not surprising that there remains competing hypotheses regarding the nature of solitude and its implications for well-being. Indeed, from our view, these fundamentally opposed differential characterizations of solitude represent the most pervasive theme in the historical study of solitude as a psychological construct. In essence, this ongoing debate about the nature of solitude can be distilled down to an analysis of its costs versus benefits.

Solitude is bad

Social affiliations are relationships that have long been considered to be adaptive to the survival of the human species (Barash, 1977). Indeed, social groups offer several well-documented evolutionary advantages (e.g., protection against predators, cooperative hunting, and food sharing) (Hamilton, 1964; Trivers, 1971). The notion that solitude may have negative consequences has a long history and can literally be traced back to biblical times (Genesis 2:18, And the LORD God said “It is not good for the man to be alone”).

Within the field of psychology, Triplett (1898) demonstrated in one of the earliest psychology experiments that children performed a simple task (pulling back a fishing reel) more slowly when alone than when paired with other children performing the same task. Thus, at the turn of the century, it was clear that certain types of performance were hindered by solitude. Developmental psychologists have also long suggested that excessive solitude during childhood can cause psychological pain and suffering (e.g., Freud, 1930), damage critically important family relationships (e.g., Bowlby, 1973; Harlow, 1958), impede the development of the self-system (Mead, 1934; Sullivan, 1953), and prevent children from learning from their peers (e.g., Cooley, 1902; Piaget, 1926). The profound psychological impairments caused by extreme cases of social isolation in childhood, in cases such as Victor (Lane, 1976) or Genie (Curtiss, 1977), have emphasized that human contact is a basic necessity of development.

Social psychologists have also long considered the need for affiliation to be a basic human need (Horney, 1945; Shipley & Veroff, 1952). Early social psychology studies on small group dynamics, such as the Robbers Cave experiments (Sherif, Harvey, White, Hood, & Sherif, 1961), further highlighted the ways in which intergroup conflict can emerge and how out-group members can become quickly perceived negatively and in a stereotypical fashion and become mistreated. More recently, the need to belong theory (Baumeister & Leary, 1995) has suggested that we all have a fundamental need to belong or be accepted and to maintain positive relationships with others and that the failure to fulfill such needs can lead to significant physical and psychological distress. Relatedly, social neuroscientists now suggest that loneliness and social isolation can be bad not only for our psychological functioning and well-being but also for our physical health (Cacioppo & Patrick, 2008; House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988).

Finally, from the perspective of clinical psychology, social isolation has been traditionally viewed as a target criterion for intervention (Lowenstein & Svendsen, 1938). In the first edition of the Diagnostic statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-I; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1952), people who failed to relate effectively to others could be classified as suffering from either a psychotic disorder, such as schizophrenia; a psychoneurotic disorder, such as anxiety; or a personality disorder, such as an inadequate personality (characterized by “inadaptability, ineptness, poor judgment, lack of physical and emotional stamina, and social incompatibility”; p. 35). In the DSM-I, schizoid personality disorder is described as another personality disorder characterized by social difficulties, specifically social avoidance. Interestingly, children with schizoid personalities were described in the manual as quiet, shy, and sensitive; adolescents were described as withdrawn, introverted, unsociable, and as shut-ins.

Solitude can be good

In stark contrast, and from a very different historical tradition, many theorists and researchers have long called attention to the benefits of being alone (Montaigne, 1965; Merton, 1958; Zimmerman, 1805). For example, a central question for ancient Greek and Roman philosophers was the role of the group in society and the extent to which the individual should be a part of and separate from the group in order to achieve wisdom, excellence, and happiness. Later, Montaigne acknowledged the difficulties of attaining solitude but argued that individuals should strive for experiences of solitude to escape pressures, dogma, conventional ways of thinking and being, vices, and the power of the group. For Montaigne, the fullest experiences of solitude could not be guaranteed by physical separation from others; instead, solitude involved a state of natural personal experience that could be accomplished both alone and in the company of others. Related ideas can be found in religious writings and theology (Hay & Morisey, 1978). For example, Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk who spent many years in solitude, passionately argued in several books and essays that solitude offered unique experiences for contemplation and prayer and that solitary retreats are necessary to achieve authentic connections with others.

Ideas about the benefits of solitude can also be found in the writings of Winnicott (1958). For Winnicott, solitude was an experience of aloneness afforded by a good-enough facilitating environment and was a necessary precondition during infancy and childhood for later psychological maturity and self-discovery and self-realization. In adulthood, spending time alone and away from others has also long been argued by philosophers, authors, and poets to be necessary for imaginative, creative, and artistic enterprises (e.g., Thoreau, 1854). In these perspectives, solitary experiences provide benefits when the individual chooses to be alone. However, personal stories of several accomplished authors, such as Beatrix Potter and Emily Dickinson, suggest that creativity and artistic talents may also develop in response to long periods of painful social isolation and rejection (Middleton, 1935; Storr, 1988).

Underlying mechanisms of solitude

Although the costs versus benefits debate regarding solitude is somewhat all-encompassing, nested within this broader distinction is a theme pertaining to the different mechanisms that may underlie our experiences of solitude. To begin with, it is important to distinguish between instances when solitude is other-imposed versus sought after. Rubin (1982) was one of the first psychologists to describe these different processes as distinguishing between social isolation, where the individual is excluded, rejected, or ostracized by their peer group, and social withdrawal, where the individual removes themselves from opportunities for social interaction. As we have previously discussed, there are long-studied negative consequences that accompany being socially isolated from one’s group of peers. Thus, we turn now to a consideration of varying views regarding why individuals might chose to withdraw into solitude.

Within the psychological literature, researchers have highlighted several different reasons why individuals may seek out solitude, including a desire for privacy (Pedersen, 1979), the pursuance of religious experiences (Hay & Morisey, 1978), the simple enjoyment of leisure activities (Purcell & Keller, 1989), and seeking solace from or avoiding upsetting situations (Larson, 1990). Biological and neurophysiological processes have also been considered as putative sources of solitary behaviors. For example, the ancient Greeks and Romans argued that biologically based individual differences in character help to determine mood (such as fear and anxiety) and social behavioral patterns (such as the tendency to be sociable or not), ideas which were precursors to the contemporary study of child temperament (Kagan & Fox, 2006). As well, recent interest in the specific neural systems that may be involved in social behaviors can be traced to the late 1800s with the case of Phineas Gage, who injured his orbitofrontal cortex in a railroad construction accident and afterwards was reported to no longer adhere to social norms or to be able to sustain positive relationships (Macmillan, 2000).

Finally, there is also a notable history of research pertaining to motivations for social contact (e.g., Murphy, 1954; Murray, 1938), which has been construed as a primary substrate of human personality (Eysenck, 1947). An important distinction was made between social approach and social avoidance motivations (Lewinsky, 1941; Mehrabian & Ksionzky, 1970). It has since been argued that individual differences in these social motivations further discriminate different reasons why individuals might withdraw from social interactions. For example, a low social approach motivation, or solitropic orientation, is construed as a non-fearful preference for solitude in adults (Burger, 1995; Cheek & Buss, 1981; Leary, Herbst, & McCrary, 2001) and children (Asendorpf, 1990; Coplan, Rubin, Fox, Calkins, & Stewart, 1994). In contrast, the conflict between competing social approach and social avoidance motivations (i.e., approach–avoidance conflict) is thought to lead to shyness and social anxiety (Cheek & Melchior, 1990; Jones, Briggs, & Smith, 1986).

Developmental timing effects of solitude

Our final theme has to do with developmental timing or when (or at what age/developmental period) experiences of solitude occur. The costs of solitude are often assumed to be greater during childhood than in adolescence or adulthood – given the now widely held notion that the young developing child requires a significant amount of positive peer interaction for healthy social, emotional, and social-cognitive development and well-being (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006). This pervasive belief may explain, in part, why considerably more developmental research on the concomitants of social withdrawal has focused on children as compared to adolescents. In addition, it is during adolescence that increasing needs for and enjoyment of privacy and solitude are thought to emerge (Larson, 1990). For this reason, it has been posited that some of the negative peer consequences often associated with social withdrawal during childhood, such as peer rejection and peer victimization, may diminish during the adolescent developmental period (Bowker, Rubin, & Coplan, 2012).

However, it has also long been argued that solitude at any age can foster loneliness and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Contributors

- Foreword: On Solitude, Withdrawal, and Social Isolation

- Part I : Theoretical Perspectives

- Part II : Solitude Across the Lifespan

- Part III : Solitude Across Contexts

- Part IV : Clinical Perspectives

- Part V : Disciplinary Perspectives

- Index