eBook - ePub

Clinician's Guide to Self-Renewal

Essential Advice from the Field

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Clinician's Guide to Self-Renewal

Essential Advice from the Field

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Providing clinicians with advice consistent with the current emphasis on working from strengths to promote renewal, this guide presents a holistic approach to psychological wellness. Time-tested advice is featured from experts such as Craig Cashwell, Jeffrey Barnett, and Kenneth Pargament. With strategies to renew the mind, body, spirit, and community, this book equips clinicians with guidance and inspiration for the renewal of body, mind, community, and spirit in their clients and themselves.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Clinician's Guide to Self-Renewal by Robert J. Wicks, Elizabeth A. Maynard, Robert J. Wicks, Elizabeth A. Maynard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Psychotherapy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Self-Renewal and the Clinician

Chapter 1

Growth, Love, and Work in Psychotherapy: Sources of Therapeutic Talent and Clinician Self-Renewal

Helene Nissen-Lie and David E. Orlinsky

Successful psychotherapy can be seen as a process that essentially involves self-renewal. This is most apparent in the lives of clients, where self-renewal implies the restoration of normal development for those whose personal growth had been limited or distorted by adverse life circumstances. In therapy, that restoration is accomplished through the client’s personal involvement in a professional relationship that combines meaningful challenge with support and encouragement. This requires a commitment of emotional energy reflected in the client’s motivation for therapy and hopeful morale about eventual positive outcome—an investment of energy that must be sustained and renewed through experiencing the therapist’s personal interest, empathic responsiveness, and effective interventions.

Less apparent, perhaps, is the fact that psychotherapy also requires and relies on the clinician’s experiences of self-renewal, because clinicians too need to participate personally (in a special but essential sense) in their professional relationships with clients. Therapists invest and expend a significant amount of emotional and intellectual energy in order to be personally present—alert, attuned, and empathically responsive to clients—and to provide each client with realistic challenges and meaningful support in ways well suited to the client’s level of need, state of mind, and stage of progress.

Providing psychotherapy is demanding work, both intellectually and emotionally. Maintaining one’s morale can be difficult when working with clients who are in deep emotional turmoil, often having experienced traumatic childhoods or devastating life circumstances. Clients who have experienced disruptive breaches of trust on the part of those they once depended on often exhibit defensive behavior in therapy, criticizing therapists for perceived slights and rejecting well-intended interventions, or else idealizing them and burdening them with insatiable neediness, or yet again engaging in distressing destructive or self-destructive behaviors.

Coping constructively with conditions like these requires a high level of interpersonal skill on the part of psychotherapists, and a resilient core of emotional equilibrium. Some of those interpersonal skills are acquired or enhanced through professional training and experience in practice, but the basic interpersonal skills and capacities that therapists need to deal effectively with challenging clients derive in large part from formative experiences in their own personal development that can be described as therapeutic talent—abilities that therapists already have when they come for professional training, and which undoubtedly can be refined and augmented by training and experience but probably cannot be produced by training alone if they are not already present (Orlinsky, Botermans, & Rønnestad, 1998). Similarly, the motivations that lead therapists to apply for professional training, and need in order to engage in therapeutic work, stem in large part from formative personal experiences in their own development, and are renewed and maintained both by successful practice and by personal experiences of current life satisfactions that help them maintain a positive emotional equilibrium.

This chapter is devoted to exploring some sources of clinicians’ talents and motivations for psychotherapeutic work, and some of the long- and short-term self-renewal that work to maintain them. The first of its two main sections (by Orlinsky) presents a theoretical model of personal development that explores the interconnected themes of personal growth, love relationships, and the development of capacities that define therapeutic talent. The second section (by Nissen-Lie) reflects on therapists’ private lives with respect to the personal factors that motivate therapists to pursue their profession and the resources in their private lives that sustain them in their work.

I. PERSONAL GROWTH, LOVE, AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THERAPEUTIC TALENT

This section explores the idea that therapeutic talent is rooted in the personal development of the psychotherapist. The talent itself consists of the therapist’s personal ability to engage clients in a supportive and challenging professional psychotherapy relationship. Research on therapeutic process and outcome has amply documented that the client’s experience of a strong positive therapeutic bond consistently predicts improvement in clinical outcome (Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger, & Symonds, 2011). This personal/professional therapeutic bond reflects and depends to a significant degree on the interpersonal skills and capacities of the therapist that are initially developed in the course of the therapist’s personal growth. The following section offers a conception of personal development and suggests distinctive aspects of therapeutic talent traceable to that development.

Personal Growth

Personal growth can be defined as the progressive differentiation and subsequent integration of experience (e.g., Angyal, 1941; Lewin, 1935; Werner, 1942) that alternately distinguish the self from others (individuation) and intimately connect the self with others (interdependence). The result is a cumulatively more complex set of self-other experiences (e.g., Sullivan, 1949) that constitute the interrelated spheres of ego-identity and object-world, which composes the individual’s personality.

Alternating and successive phases of individuation and interdependence generate a dialectical pattern of development mediated through a person’s close relationships with others—relationships in forms and ways that are appropriate to each specific stage of life. Accompanied by newfound pleasures as well as growing pains and eventual experiences of loss, the close relationships that emerge in each phase of development promote personal growth by alternately stretching the individual’s capacities for asserting a clear self-presence, and for merging in mutual and mutually beneficial interdependence with others.

Individuation occurs through relationships of self-assertion that frequently result in contentious interpersonal behaviors. Examples of this are the willfulness shown by toddlers in their “terrible twos,” by the oedipal and sibling rivalries of early childhood, and by later competition for dominance when relating with peers. Growth through successive phases of self-assertion and self-realization involves putting together and putting forward a distinct, and distinctive, socially viable identity—pushing others, sometimes against others, to recognize and respect one’s presence.

Growth through successive phases of interdependence occurs through involvement in age-appropriate love relationships (Orlinsky, 1972). Each new phase of growth-through-love thrusts the individual into experiencing a relationship that transcends the self, and that evokes a new aspect or facet of self through which the individual can connect with other persons.

The alternating phases of growth serve as prerequisites for subsequent phases of development. Thus, each phase of individuation generates a new aspect of self-experience that incorporates the experience of the person in the most recent phase of love attachment, and integrates that with aspects of self that had been generated in prior phases of individuation. In a similar way, each phase of interdependence generates a new capacity for involvement in close relationships that incorporates the experience of self in the most recent phase of individuation, and integrates that with capacities for closeness that had been generated in prior phases of interdependence.

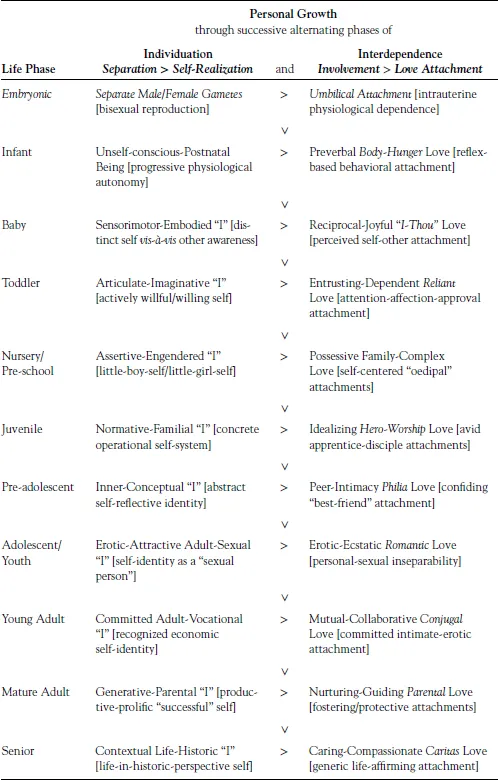

Table 1.1 presents a highly schematic chart showing the alternating successive phases of personal growth as socially and culturally configured in late 20th century Western societies (cf. Kakar, 1981, for an example of a contrasting cultural pattern). This conception is based largely on ideas advanced by writers like Freud (1917/1963), Erikson (1950, 1959a), Piaget (Piaget & Inhelder, 1969), Sullivan (1953), and Bowlby (1969). Before commenting on specific phases, it is important to note that Table 1.1 shows an ideal pattern—a societally specific cultural normative pattern that empirically, in the lives of real individuals, is traceable only more or less clearly due to the influence of many circumstances. It is also important to note that phases of growth may overlap and interfere with one another, especially when one phase is closing and the next is starting.

Table 1.1 Phases of Personal Growth

Mastery of the developmental challenges in each phase may be abbreviated and incomplete, leaving the persons in question unprepared for challenges that their future holds. Adaptations in each phase may be distorted or disrupted by traumatic experiences that leave the survivor overly sensitive and potentially vulnerable in later life. Real persons always grow imperfectly, often deficiently, and occasionally defectively, according to an ideal cultural pattern of development.

Growth Through Love and the Accrual of “Therapeutic Talent”

The first phases of individuation and interrelatedness take place in the context of the child-parent relationship (“parent” understood as caregiver), which extends over many years and changes in character and tone as the child grows physically, cognitively, and emotionally. Interrelatedness and individuation start within the womb on a biological level, the first phase of interdependence being one of umbilical attachment, and the first phase of individuation culminating in birth.

Infancy

For the parent, this phase in the child-parent relationship represents an intensely focused and extremely conscious experience of love. For the infant, the attachment is initially reflexive, and unfolds a diffuse and pervasive but essentially unself-conscious embodied experience of hunger, distress, and discomfort, followed more or less reliably by satisfaction, safety, and pleasure—which, if not yet experienced distinctly as a love relationship, is the ground and foundation of all later love relationships (Bowlby, 1969; Erikson, 1950; Stern, 1985).

Babyhood

The baby’s ability to consciously experience love as an active exchange in attachment with a caregiver depends on the psychological development of a “self ”—the first psychological individuation—made possible as a result of the child’s sensorimotor, cognitive, and affective maturation during the first six to nine months of postnatal life. One becomes increasingly able to differentiate between “inner” experiences of more or less urgent need and “outer” experiences of a world in which Others who gratify (but sometimes also frustrate, irritate, and frighten) recurrently appear to attend to it.

This step in self-realization makes possible and introduces a phase of genuine attachment-love for the infant-child, an encompassing holistic experience of recognition and affirmation by—and deep and wholehearted affirmation of—a powerful, responsive, and benignly sustaining presence. This phase reflects the development of love in a primal “I-Thou” relationship, an intimacy that can only be felt rather than spoken because it is grounded more deeply in experience than words (Buber, 1965).

Later, in the lives of therapists, this early experience enables them to be present to clients in a steady, deeply affirming way—to engage with, witness, and comfort their distress—and enables clients to receive this as a healing gift. The aspect of relational talent that derives from it is well described as “therapeutic presence.”

Toddlerhood

The next cycle of individuation and attachment also occurs in the context of the child-parent relationship as the child becomes more mobile, verbally articulate, and socially discriminating between 18 months and 3 years of age. Now possessing a stable/continuous sense of self, the toddler begins to employ and practice its new capacities for self-direction, self-...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the Book

- About the Editors

- About the Authors

- Self-Renewal Themes in Psychotherapy: An Introduction

- Part I: Self-Renewal and the Clinician

- Part II: Alonetime, Mindfulness, the Sabbath, Natural Empathy: Loving Kindness, Zen Therapy, and Self-Renewal

- Part III: Trauma, Growth, Healing, Patience, Forgiveness, Courage, and the Process of Renewal

- Part IV: Theoretical Approaches to Self-Renewal: Group, Marital, and Family System, Dialectical, Behavioral, and the Ways Paradigm

- Part V: Spirituality and Self-Renewal

- Part VI: Topics in Self-Renewal

- Going Forward: A Brief Epilogue

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- End User License Agreement