This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

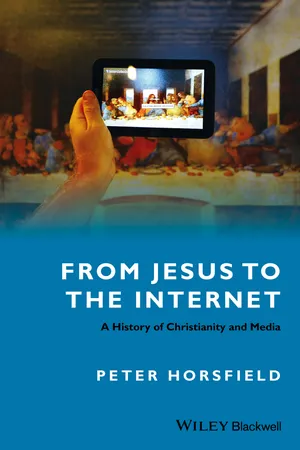

From Jesus to the Internet examines Christianity as a mediated phenomenon, paying particular attention to how various forms of media have influenced and developed the Christian tradition over the centuries. It is the first systematic survey of this topic and the author provides those studying or interested in the intersection of religion and media with a lively and engaging chronological narrative. With insights into some of Christianity's most hotly debated contemporary issues, this book provides a much-needed historical basis for this interdisciplinary field.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access From Jesus to the Internet by Peter Horsfield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

In the Beginning

Investigating who Jesus was and how Christianity began is a media phenomenon in itself. It is difficult now to distill the original figure of Jesus from the memories, recollections, accumulations, inventions, myths, and interpretations that have become part of the Christian mediation of him, even in its earliest documents.1 For some, getting a reasonable historical picture of Jesus is either not possible, not important, or not a question. But there’s value in attempting to do so, in order to get at least an approximation of what was there in the beginning, as a basis for understanding how and why it’s changed and which factors influenced the changes.

What has commonly been known about the history of Jesus and the beginning of Christianity comes from copies of copies of a relatively small number of written documents reproduced in what is now called the New Testament, comprising four Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, and a number of letters. But these texts have particular characteristics that need to be considered in building an accurate picture.

One is that they did not begin to be written or compiled until at least twenty years after Jesus had been killed and a post-Jesus movement was underway. Although significant weight is given by many scholars to the dependability of the preservation of the events of Jesus in a Christian oral tradition,2 much had happened in those intervening decades and there is evidence that some of those later events and the ideas that came out of them were taken up and included in the writing about Jesus as if they were part of Jesus’ own story.

A second is that these key documents in the New Testament are just a few of a much larger number of documents also written about the same events. This larger corpus of documents were culled over a period of several hundred years in an ideological process of selection to create an authorized version of the history (a canon) that reflected the interests of those in power at the time. Many of those other documents, which offered alternative viewpoints, were destroyed in what we would now call a process of media censorship and control.

A further consideration is that these few select documents are nothing like what we would call objective or balanced historical recording. They are partisan, creative, retrospective, interpreted reconstructions of something that happened several decades earlier by a passionate social minority group with a vested interest. Borg identifies them as testimony rather than what we understand as history, and they should be read therefore for their meaning and not primarily for their factuality.3

A final consideration is that the texts are a specific medium – writing. Although almost all of the earliest Christians were illiterate, the perspectives we have today on who Jesus was and what he did are the views of an unrepresentative group of literate Christians who made up less than 5% of the Christian community at the time.

There has been a significant scholarly interest from the start of the twentieth century to apply modern historical critical methods to these writings to try to separate out the more historical aspects of Jesus from later inventions and accumulations, in order to locate Jesus more accurately within the social, cultural, and religious milieus of his time. Some of the findings of this research have been controversial and in many cases contradict orthodox Christian beliefs. Many are still being debated.4 Rather than one conclusion, at best what has been reached are a number of possible options, with Jesus being portrayed variously as a peasant sage, a social revolutionary, a religious mystic, a prophet of the end time, a marginal Jew, or the true Messiah.5

It is beyond the scope of this work to try to resolve issues that are unresolved by highly qualified biblical scholars. However, this body of research offers valuable insights that can be useful in getting a clearer picture of what Jesus may have thought and what he was doing. As Borg notes, Jesus ceases to be a credible figure and loses his humanness if attributes properly belonging to his followers after his death are ascribed to him before his death – it is “neither good history nor good theology.”6 Since the field is still a hotly contested one, what follows is my educated reading of that recent thinking compiled to give us a framework for understanding Jesus’ thought and practice, and for reconsidering the development of thought and practice that followed him and the place of media in those developments.

The social and media context

Jesus was born and spent much of his life in the ancient Roman Middle Eastern region of Galilee. Because of its position on the trade routes between Asia Minor and Egypt, for more than a thousand years, the wider area of Palestine had negotiated its religious and political identity amid constant imperial occupations and cultural colonization. At the time of Jesus it was part of the Roman Empire, governed by rulers appointed by Rome according to Roman policy.

The Jewish society into which Jesus was born was diverse and highly stratified socially, economically, and religiously. Communication patterns and practices reflected and reinforced these class distinctions. The languages one spoke, the circumstances in which they were spoken, how they were spoken, whether one was literate in a particular language or another, and the extent of one’s literacy were all markers of a person’s or group’s identity and place within the local and imperial cultural hierarchies. Three languages in particular were important in social positioning and stratification. Greek was the dominant language used in urban areas in business, international politics, and secular culture. Hebrew was the language of Jewish scriptures, and it was used primarily in the Temple and Jewish religious literature and practice. Its restricted use and literacy had led to the development of a religious leadership class based primarily on their capacity and resources to read and speak Hebrew. Aramaic, which had a number of dialects, was the common and most widely used language in general discourse and village life.

Levels of literacy were low and generally restricted to the upper classes. While there is a variety of opinions about levels of literacy, the estimation is that from 95 to 97 percent of the population were illiterate,7 meaning that interactions of social and religious life, particularly in the towns and rural areas, were almost wholly oral in character.

Despite the general low levels of literacy, the religion of Jesus was a blended oral and literate religious culture. For hundreds of years, the Jews in Exile, in Israel, and in the Diaspora had been assembling and reproducing written scriptures and other texts. Protocols had been developed for how these written documents were to be integrated into worship, teaching, and wider oral practices of the religion. Different Jewish religious groups were marked not only by differences in their religious and cultural views, but also by different traditions of the integration of text into oral practice. These included the Sadducees, the hereditary priestly families and landholding aristocrats of Jerusalem; the Pharisees, a religious group marked by their piety born of struggles against secularizing trends a century earlier; the Scribes, a literate group who played a powerful role interpreting the written texts of the religion; and the Essenes, an apocalyptic sect and monastic community of Judaism.

For those living outside Jerusalem or without access to the Temple, the center of religious community was the local synagogue, a primarily lay-oriented community that stressed reading or recitation of the Hebrew scriptures, exposition of the scriptures when there was a person present who could do it, singing of hymns, and offering of prayers. Although illiterate, most heard the scriptures spoken sufficiently frequently to be able to recite significant portions of them from memory. Since most village people spoke Aramaic, a practice developed of providing oral Aramaic interpretations and applications of the Hebrew scripture readings, known as targums. When the Jerusalem Temple was destroyed in 70 CE, the synagogue form of worship with its combination of reading or reciting scriptures with oral commentary and debate became the common form of worship in reformed Rabbinic Judaism. In its early development, Christian communities drew significantly on this media model in the development of Christian worship practice.

A major issue in people’s daily lives was making enough not only to provide the basic necessities of life but also to meet the financial burden of taxation. The Romans imposed heavy taxes, tolls, and tributes on occupied populations to support their imperial activities, the military, and the ruling elite. Depending on occupation and location, these imperial tax obligations could range from 12% to 50%.8 Collection of taxes was leased out by the Romans to the local upper stratum, including religious leaders, who added to the imperial tax obligation their own costs and profits. These were ruthlessly collected, with military support provided to local tax collectors if needed. Jews were also obligated to pay religious tithes and taxes, specified in the Torah as part of the Covenant, for the support of the temple, its priests, and the poor. For farmers, the combined Jewish and Roman taxes were around 35 percent.9

For those living already at a marginal or subsistence level, meeting these obligatory taxes was crippling. In an empire that was dominantly agricultural, income and wealth were tied significantly to ownership of land. Those whose traditional or inherited land was not large or fruitful enoug...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: In the Beginning

- Chapter 2: Making Jesus Gentile

- Chapter 3: The Gentile Christian Communities

- Chapter 4: Men of Letters and Creation of “The Church”

- Chapter 5: Christianity and Empire

- Chapter 6: The Latin Translation

- Chapter 7: Christianity in the East

- Chapter 8: Senses of the Middle Ages

- Chapter 9: The New Millennium

- Chapter 10: Reformation

- Chapter 11: The Modern World

- Chapter 12: Electrifying Sight and Sound

- Chapter 13: The Digital Era

- Conclusion

- References

- Index

- EULA