- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Organised into 9 parts that highlight a wide range of architectural motives, such as 'Architecture as Theatre', 'Stretching the Vocabulary' and 'The City of Large and Small', the workbook provides inspiring key themes for readers to take their cue from when initiating a design. Motives cover a wide-range of work that epitomise the theme. These include historical and Modernist examples, things observed in the street, work by current innovative architects and from Cook's own rich archive, weaving together a rich and vibrant visual scrapbook of the everyday and the architectural, and past and present.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

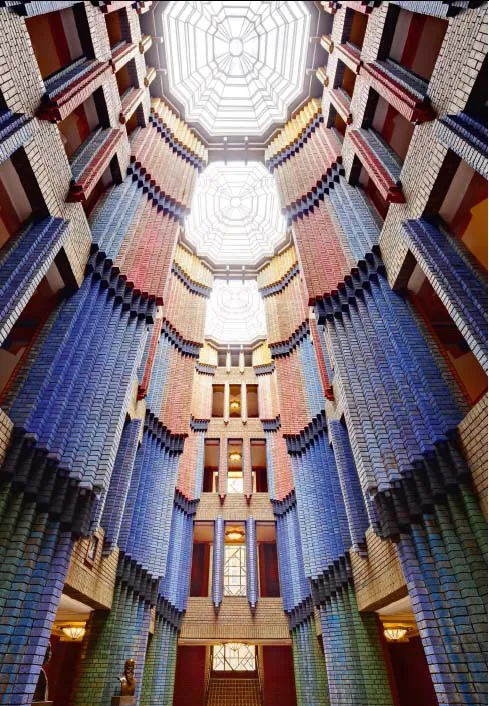

Peter Behrens, administration building, Hoechst Chemical Works, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1924: main hall.

An artist-turned-architect, Behrens created not only a dramatic – almost Gothic – space, but accentuated its sense of ‘theatre’ by an assiduous use of stratified colour.

MOTIVE 1 ARCHITECTURE AS THEATRE

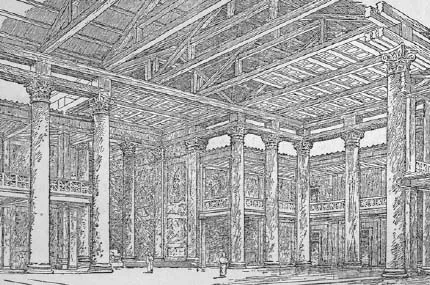

Vitruvius, basilica at Fano, Italy, 19 BC.

This is the only known built work of Vitruvius, effectively the first architectural theorist. If the visualisation is to be believed, it suggests that already by this time ‘classical’ mannerisms had already established themselves.

Thinking about architecture, I have rarely felt the need to detach myself from the circumstances around me – and certainly not by recourse to any system of abstraction. For this reason, most of the work discussed in this book is influenced by the episodic nature of events, by the coincidental, the referential, and is unashamedly biased. It seeks no truths but it enjoys two parallel areas of speculation: the ‘what if?’ and the ‘how could?’ that can be underscored by many instances of ‘now here’s a funny thing’.

Thus each chapter revolves around a motive – acting as a catalyst or driver of the various enthusiasms or observations, clarifying the identity of those same ‘what ifs?’ and ‘how coulds?’. In each case the motive is elaborated upon by a commentary that tries to observe the world around us and the ironies and layers of our acquired culture. This precedes the description of the work itself. Of course there are times when such observations do or do not have any direct reference to what follows: yet I would claim that they sit there all the time, an experiential or prejudicial underbelly without which the description would lose dimension.

I do have a core belief, which I introduce here as the first motive: that for me, architecture should be recognised as theatre, in the sense that architecture should have character. It should be able to respond to the inhabitant or viewer and prepare itself for their presence, spatially; in other words, it should have that magic quality of theatre, with all its emphasis on performance, spectacle and delight.

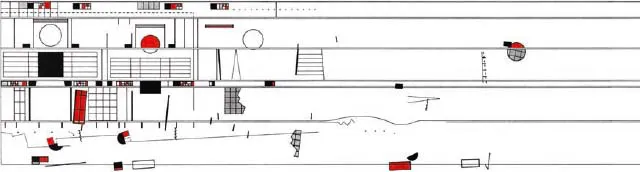

Bernard Tschumi, National Theatre and Opera House, Tokyo, 1986.

A competition project that demonstrates Tschumi’s often-demonstrated ability to create a very clear concept and strategy for a building; a figure that also recalls 20th-century musical scores.

Indulging in Delight

If the Ancient Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius came out in favour of ‘firmness, commodity and delight’ as the key elements of architecture in his celebrated treatise De architectura (Ten Books on Architecture), we are by now, in the Western world, so statutorily bound into systems of checks and balances – standards, codes and building inspections – that non-firmness is unlikely. Yet commodity can be more: it is not just the common-sense placing of things, for these can also be placed wittily – and thus lead directly to the experience of delight. It is only dull architects who are immediately happy if buildings just have everything in the right place and leave it at that. But delight. This is a contentious beast; it involves evaluation, sensitivity, and even that difficult issue: taste.

What delights one irritates another, but both are alerted: their world is for the moment extended, identified, stopped in its tracks. If buildings are the setting for experience, then we may ask: can they influence that experience? It could be argued that people who are totally self-obsessed, or under extreme pressure, or blind, or in an extreme hurry … may not notice where they are. But for the rest, the combination of presence, atmosphere, procedure and context add up to something that architecture should be aware of.

It is challenging to the notion of delight when the architect and writer Bernard Tschumi asserts the predominance of ‘concept’ to design in architecture, which seems to suck all the pleasure out of it. It immediately prompts me to substitute the word ‘concept’ with ‘idea’ – which is of course more emotive and less controlling than concept, or maybe comes a little before it. I would claim for ‘idea’ that it can be very affected by those same layers of ‘what if’ and ‘how could’ that may then sway or load up upon a concept and cause it to be unevenly but interestingly unbalanced. In the end, of course, Tschumi has wit and taste, as demonstrated by his unexecuted competition design for the National Theatre and Opera House, Tokyo (1986).

Partisan abstraction seems so often to be the province of the pious or the creatively untalented. It is so easy for them to wave a finger at us indulgers and enthusiasts, to constantly ask us to define our terms of reference and then posit some unbelievably dull terms of their own with (if at all) unbelievably boring architectural implications.

Discovering Novelty in the Known

I was always fascinated by the very creative mythology and spirituality of the New York architect, poet and educator John Hejduk (1929–2000) – who was Dean at the Cooper Union School of Art and Architecture for 25 years. In his investigations of freehand ‘figure/objects’, which expressed his own poetry, and his rare built works, like Security for Oslo (1989), I admired his ability to gaze beyond the logical world. The latter structure, originally conceived for Berlin, was erected by staff and students of the Oslo School of Architecture and placed on a site that had been heavily used by the Nazis when occupying Norway. However, I remain a little squeamish about symbolism and the unknown, and so I tend to retreat back into the comfort of tangible reference.

At this point the observer might ask how it is then possible for such a mind to suggest the new or the less-than-usually-likely. Naively, I would answer that almost every project is suggesting the possible and has its hind legs in the known. In fact those that don’t are the ones that tend to be forgettable. The interesting thing is that the references can be scrambled, the antecedents taken from anywhere; they just have to contain enough consistency to make the scene.

For so long I trod the corridors of schools of architecture, and served as Chair and Professor of the Bartlett School of Architecture (UCL), creating an architectural milieu. Even now that I am back in practice with Gavin Robotham at CRAB (Cook Robotham Architectural Bureau), having 95 per cent of my conversations with other architects (including those at home), the danger is that one makes too many assumptions and moves within a referential comfort zone. In this circumstance, the theatre of architecture could easily become a run longer than Agatha Christie’s play The Mousetrap (which at the time of writing is celebrating its 63rd consecutive year of performances in London’s West End), in which every move and every nuance is predicted by the audience. Such a condition might dangerously lead to a tradition or a system.

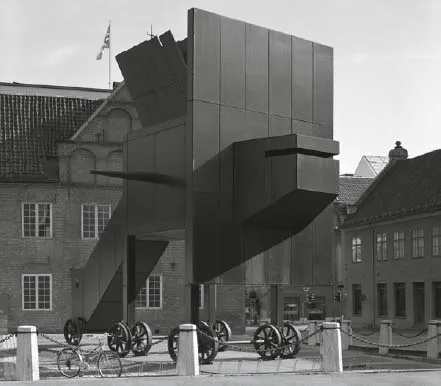

John Hejduk, Security, Christiania Square, Oslo, 1989.

Designed for the City of Oslo and constructed by faculty and students of the Oslo School of Architecture, Hejduk’s brooding creation symbolised a series of conceptual layers appropriate to a place that was the Nazi headquarters during Norway’s occupation between 1940 and 1945.

Thus there is a consciou...

Table of contents

- Cover

- TitlePage

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Motive 1 Architecture as Theatre

- Motive 2 Stretching the Vocabulary

- Motive 3 University Life and its Ironies

- Motive 4 From Ordinary to Agreeable

- Motive 5 The English Path and the English Narrative

- Motive 6 New Places and Strange Bedfellows

- Motive 7 Can We Learn from Silliness?

- Motive 8 The City – Then the Town

- Motive 9 On Drawing, Designing, Talking and Building

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Picture Credits

- EULA

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Architecture Workbook by Sir Peter Cook in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.