eBook - ePub

The Complete Archaeology of Greece

From Hunter-Gatherers to the 20th Century A.D.

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Complete Archaeology of Greece covers the incredible richness and variety of Greek culture and its central role in our understanding of European civilization, from the Palaeolithic era of 400, 000 years ago to the early modern period. In a single volume, the field's traditional focus on art and architecture has been combined with a rigorous overview of the latest archaeological evidence forming a truly comprehensive work on Greek civilization.

*Extensive notes on the text arefreely available online at Wiley Online Library, and include additional details and references for both the serious researcher and amateur

- A unique single-volume exploration of the extraordinary development of human society in Greece from the earliest human traces up till the early 20th century AD

- Provides 22 chapters and an introduction chronologically surveying the phases of Greek culture, with over 200 illustrations

- Features over 200 images of art, architecture, and ancient texts, and integrates new archaeological discoveries for a more detailed picture of the Greece past, its landscape, and its people

- Explains how scientific advances in archaeology have provided a broader perspective on Greek prehistory and history

Selected by Choice as a 2013 Outstanding Academic Title

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Complete Archaeology of Greece by John Bintliff in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The Landscape and Aegean Prehistory

1

The Dynamic Land

Introduction

Greece is a land of contrasts (Admiralty 1944, Bintliff 1977, Higgins and Higgins 1996: and see Color Plate 0.1). Although promoted to tourists for its sandy beaches, rocky headlands, and a sea with shades of green and blue, where Aleppo pine or imported Eucalyptus offer shade, in reality the Greek Mainland peninsula, together with the great island of Crete, are dominated by other more varied landscapes. Postcard Greece is certainly characteristic of the many small and a few larger islands in the Cycladic Archipelago at the center of the Aegean Sea, the Dodecanese islands in the Southeast Aegean, and the more sporadic islands of the North Aegean, but already the larger islands off the west coast of Greece such as Ithaka, Corfu, and Kephallenia, immediately surprise the non-Mediterranean visitor with their perennial rich vegetation, both cultivated trees and Mediterranean woodlands. The Southwest Mainland is also more verdant than the better known Southeast.

The largest land area of modern Greece is formed by the north–south Mainland peninsula. At the Isthmus of Corinth this is almost cut in two, forming virtually an island of its southern section (the Peloponnese). Although in the Southeast Mainland there are almost continuous coastal regions with the classic Greek or Mediterranean landscape, not far inland one soon encounters more varied landforms, plants, and climate, usually through ascending quickly to medium and even higher altitudes. There are coastal and inland plains in the Peloponnese and Central Greece, but their size pales before the giant alluvial and karst (rugged hard limestone) basins of the Northern Mainland, a major feature of the essentially inland region of Thessaly and the coastal hinterlands further northeast in Macedonia and Thrace. If these are on the east side of Northern Greece, the west side is dominated by great massifs of mountain and rugged hill land, even down to the sea, typical of the regions of Aetolia, Acarnania, and Epirus.

Significantly, the olive tree (Figure 1.1), flourishes on the Aegean islands, Crete, the coastal regions of the Peloponnese, the Central Greek eastern lowlands, and the Ionian Islands, but cannot prosper in the high interior Peloponnese, and in almost all the Northern Mainland. The reasons for the variety of Greek landscapes are largely summarized as geology and climate.

Geological and Geomorphological History

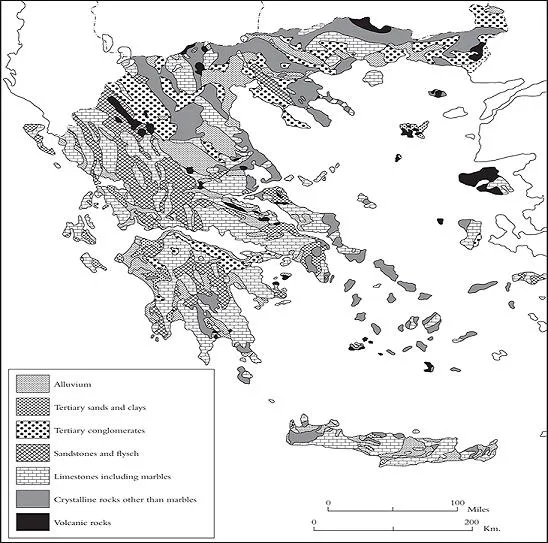

Although there are many areas with very old geological formations (Figure 1.2: Crystalline Rocks), the main lines of Greek topography were formed in recent geological time, resulting from that extraordinary deformation of the Earth’s crust called the Alpine Orogeny, or mountain-building episode, which not only put in place the major Greek mountain ranges but the Alps and the Himalayas (Attenborough 1987, Higgins and Higgins 1996). In the first period of the Tertiary geological era (the Palaeogene), 40–20 million years ago, as the crustal plates which make up the basal rocks of Africa and Eurasia were crushed together, the bed of a large intervening ocean, Tethys, was compressed between their advancing masses and thrust upwards into high folds, like a carpet pushed from both ends. Those marine sediments became folded mountains of limestone (Figure 1.2: Limestone).

Figure 1.1 Distribution of the major modern olive-production zones with key Bronze Age sites indicated. The shading from A to C indicates decreasing olive yields, D denotes no or minimal production. Major Bronze Age sites are shown with crosses, circles, and squares.

C. Renfrew, The Emergence of Civilization (Study in Prehistory), London 1972, Figure 18.12. © 1972 Methuen & Co. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis Books UK.

Image not available in this digital edition.

Figure 1.2 Major geological zones of Greece.

H. C. Darby et al., Naval Geographical Intelligence Handbook, Greece, vol. 1. London: Naval Intelligence Division 1944, Figure 4.

This plate-tectonic compression created an arc-formed alignment of Alpine mountains and associated earthquake and volcanic belts (Figure 1.2: Volcanic Rocks), which begins as a NW-SE line for the Mainland mountain folds, then curves eastwards across the center of the Aegean Sea, as the E-W orientation of Crete illustrates, and also the associated island arc of volcanoes from Methana to Santorini, to be continued in the E-W ridges of the Western Mainland of Anatolia-Turkey (Friedrich 2000). The Ionian and Aegean seas have been formed by differential sinking of those lateral parts of the Alpine arc, creating the Aegean and Ionian Islands out of former mountain ridges, hence their often rocky appearance. But also there have been tectonic ruptures in different alignments, the most notable being that E-W downward fault which forms the Gulf of Corinth. The artificial cutting of the Corinth Canal in 1893 accomplished the removal of the remaining 8 km stretch left by Nature.

These plate-tectonic forces still operate today, since the Aegean region forms an active interface between the southerly African and northerly Eurasian blocks, and is itself an unstable agglomerate of platelets. Where zones of the Earth’s crust are clashing, and ride against, or force themselves under or over each other, there are notorious secondary effects: frequent earthquakes and arcs of volcanoes set behind the active plate boundaries (Color Plate 1.1). Recurrent Greek earthquakes are a tragic reality, notably along the Gulf of Corinth, and the same zone curves into Turkey with equally dire consequences. The volcanic arc runs from the peninsula of Methana in the Eastern Peloponnese through the Cycladic islands of Melos and Santorini-Thera. A secondary arc of earthquake sensitivity runs closer to Crete and its mark punctuates that island’s history and prehistory. Around 1550 years ago, a violent earthquake through the Eastern Mediterranean elevated Western Crete by up to 9 meters (Kelletat 1991), lifting Phalasarna harbor out of the ocean (Frost and Hadjidaki 1990).

The mostly limestone mountains of Mainland Greece and Crete, as young ranges, are high and vertiginous, even close to the sea. Subsequently these characteristics encouraged massive erosion, especially as sea levels rose and sank but ultimately settled at a relatively low level to these young uplands. As a result, between the limestone ridges there accumulated masses of eroded debris in shallow water, later compressed into rock itself, flysch, whose bright shades of red, purple or green enliven the lower slopes of the rather monotonously greyscale, limestone high relief of Greece (Figure 1.2: Sandstones and Flysch). For a long period in the next subphase of the Tertiary era, the Neogene, alongside these flysch accumulations, episodes of intermediate sea level highs deposited marine and freshwater sediments in the same areas of low to medium attitude terrain over large areas of Greece. These produced rocks varying with depositional context from coarse cobbly conglomerates of former torrents or beaches, through sandstones of slower river and marine currents, to fine marly clays created in still water (Figure 1.2: Tertiary Sands and Clays, Tertiary Conglomerates).

During the current geological era, the Quaternary, from two million years ago, the Earth has been largely enveloped in Ice Ages, with regular shorter punctuations of global warming called Interglacials, each sequence lasting some 100,000 years. Only in the highest Greek mountains are there signs of associated glacial activity, the Eastern Mediterranean being distant from the coldest zones further north in Eurasia. More typical for Ice Age Greece were alternate phases of cooler and wetter climate and dry to hyperarid cold climate. Especially in those Ice Age phases of minimal vegetation, arid surfaces and concentrated rainfall released immense bodies of eroded upland sediments, which emptied into the internal and coastal plains of Greece, as well as forming giant alluvial (riverborne) and colluvial (slopewash) fans radiating out from mountain and hill perimeters. We are fortunate to live in a warm Interglacial episode called the Holocene, which began at the end of the last Ice Age some 12,000 years ago. Alongside persistent plate-tectonic effects – earthquakes around Corinth, one burying the Classical city of Helike (Soter et al. 2001), earthquakes on Crete, and the Bronze Age volcanic eruption of Thera (Bruins et al. 2008) – the Greek landscape has witnessed the dense infilling of human communities to levels far beyond the low density hunter-gatherer bands which occupied it in the pre-Holocene stages of the Quaternary era or “Pleistocene” period.

The results of human impact – deforestation, erosion, mining, and the replacement of the natural plant and animal ecology with the managed crops and domestic animals of mixed-farming life – are visible everywhere, yet certainly exaggerated. Holocene erosion-deposits in valleys and plains are actually of smaller scale and extent than Ice Age predecessors. Coastal change in historic times may seem dramatic but is as much the consequence of global sea level fluctuations (a natural result of the glacial-interglacial cycle), as of human deforestation and associated soil loss in the hinterland (Bintliff 2000, 2002). (In Figure 1.2, the largest exposures of the combined Pleistocene and Holocene river and slope deposits are grouped as Alluvium.)

Globally, at the end of the last Ice Age, sea level rose rapidly from 130 meters below present, reflecting swift melting (eustatic effects) of the major ice-sheets (Roberts 1998). By mid-Holocene times, ca. 4000 BC, when the Earth’s warming reached its natural Interglacial peak, sea levels were above present. Subsequently they lowered, but by some meters only. However, due to a massive and slower response of landmass readjustments to the weight of former ice-sheets, large parts of the globe saw vertical land and continental-shelf movements (isostatic effects), which have created a relative and continuing sea level rise, though again just a few meters. The Aegean is an area where such landmass sinking has occurred in recent millennia (Lambeck 1996). The Aegean scenario is: large areas of former dry land were lost to rising seas in Early to Mid-Holocene, 10,000–4000 BC, depriving human populations of major areas of hunting and gathering (Sampson 2006). Subsequently Aegean sea levels have risen slightly (around a meter per millennium), but remained within a few meters of the 4000 BC height, allowing river deposits to infill coastal bays and landlock prehistoric and historic maritime sites.

Let me try to give you the “feel” of the three-dimensional Greek landscape. From a sea dotted with islands, the rocky peaks of submerged mountains (Color Plate 1.2a), and occasional volcanoes, the Greek coastlands alternate between gently sloping plains of Holocene and Pleistocene sediments, and cliffs of soft-sediment Tertiary hill land or hard rock limestone ridges. The coastal plains and those further inland are a combination of younger, often marshy alluvial and lagoonal sediments (usually brown hues) (Color Plate 1.2b), and drier older Pleistocene alluvial and colluvial sediments (often red hues) (Color Plate 1.3a). The coastal and hinterland plains and coastal cliff-ridges rise into intermediate terrain, hill country. In the South and East of Greece this is mainly Tertiary yellowy-white marine and freshwater sediments, forming rolling, fertile agricultural land (Color Plate 1.3b), but in the Northwest Mainland hard limestones dominate the plain and valley edges, a harsh landscape suiting extensive grazing. A compensation in hard limestone zones within this hill land, including the Northwest, is exposures of flysch, which vary from fertile arable to a coarse facies prone to unstable “badland” topography. As we move upwards and further inland, our composite Greek landscape is dominated by forbidding ridges of Alpine limestone (Color Plate 1.3a), sometimes transformed by subterranean geological processes into dense marbles. Frequently at the interface between hill land and mountain altitudes occur much older rocks: tectonic folding and faulting after the Alpine mountain-building phase has tipped up the original limestone terrain, bringing to light earlier geological formations of the Palaeozoic or pre-Alpine Mesozoic eras. They were joined by post-Orogeny localized eruptive deposits. These are dense crystalline rocks such as schists, slates, and serpentines, whose bright colors and sharp edges trace the borders between the towering grey masses of limestone and the gentler hill lands of Tertiary sandstones or flysch which make up much of the Greek intermediate elevations. The intervention of such impermeable rocks even as thin bands at the foot of limestone massifs commonly forms a spring-line, neatly lying between good arable below and good grazing land above, a prime location for human settlement. The recent volcanic deposits can be fertile arable land, if sufficient rainfall frees their rich minerals to support soil development and plant growth. Finally, in some regions of Greece, mainly the Northeast Mainland, the Orogeny played a limited role, and the mountain massifs are much older dense crystalline rocks.

Climate

As with its geology, Greece does not have a single climate (Admiralty 1944, Bintliff 1977). Our image of long dry summers and mild winters with occasional rain reflects the focus of foreign visitors on the Southeast Mainland, the Aegean islands, and lowland Crete, where this description is appropriate.

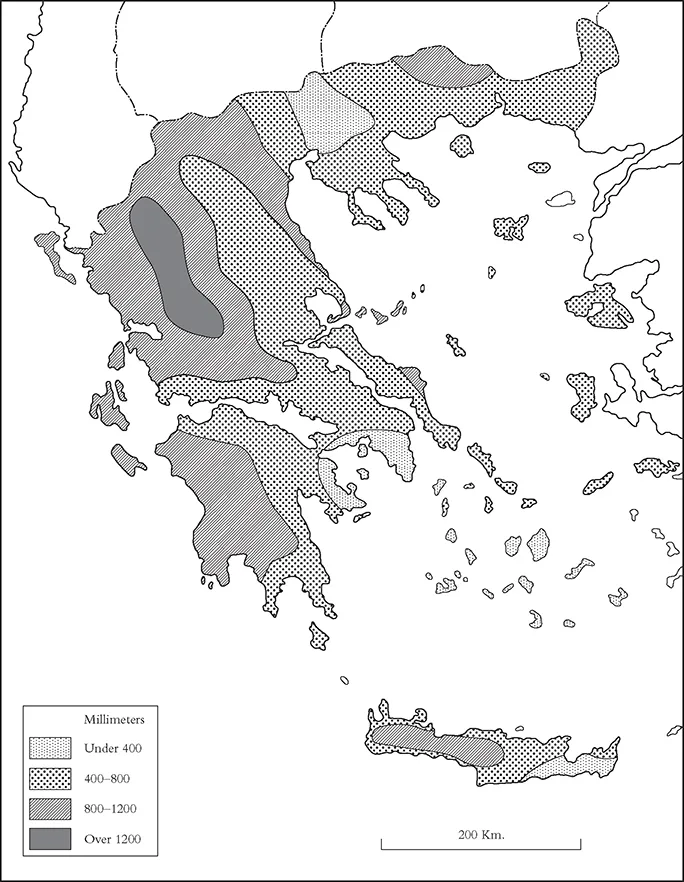

Figure 1.3 Average annual rainfall in Greece.

H. C. Darby et al., Naval Geographical Intelligence Handbook, Greece, vol. 1. London: Naval Intelligence Division 1944, Figure 59.

The two key factors in the Greek climate are the country’s location within global climate belts, and the dominant lines of Greece’s physical geography. Greece lies in the path of the Westerly Winds, so that autumn and spring rainfall emanates from the Atlantic, but is much less intense than in Northwest Europe. The Westerly rainbelt decreases in strength the further south and east you go in the Mediterranean. Most of Modern Greece has the same latitude as Southern Spain, Southern Italy, and Sicily, making all these regions strikingly more arid than the rest of Southern Europe. In summer the country lies within a hot dry weather system linking Southern Europe to North Africa. In winter cold weather flows from the North Balkans.

The internal physical landforms of the country also have a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- List of Figures and Tables

- List of Color Plates

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: The Landscape and Aegean Prehistory

- Part II: The Archaeology of Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman Greece in its Longer-term Context

- Part III: The Archaeology of Medieval and post-Medieval Greece in its Historical Context

- Plates

- Index