This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

For the student and general reader, a tour of the digital universe that offers critical observations and new perspectives on human communication and intelligence.

- Traces the development and diffusion of digital information and communication technologies, providing an analysis of trans-cultural effects among developed and developing nations

- Provides a balanced analysis of the pros and cons of the adoption and diffusion of digital technologies

- Explores privacy, censorship, the digital divide, online games, and virtual and augmented realities

- Follows a thematic structure, allowing readers to access the text at any point, based on their interests

- Accompanying resources provide a wealth of related online content

- Selected by Choice as a 2013 Outstanding Academic Title

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Digital Universe by Peter B. Seel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction and Framing

Chapter 1

The Digital Universe: A “Quick-Start” Introduction

Consumer electronic products have become so complex and feature-rich that it is now commonplace to find a brief “quick-start” guide or poster that accompanies the 100+-page manual for a new digital television set, personal computer, or mobile phone. Manufacturers understand that impatient consumers (and that includes most of us) generally skip reading the manual first – that is, until a non-intuitive feature stumps the user. Then we are likely to call the helpline instead of referring to the manual, much to the exasperation of call center agents around the world. On a positive note, quick-start guides provide enough basic information so that we can successfully install the software or power up the device and quickly begin using it.

This brief introduction serves as the “quick-start” guide for this book, which is not a manual or a how-to text for functioning in our digital world. Rather, this book provides a tour of the digital universe, tracing the evolution of the age of information from its inception to the crucial period in which we live today.1 Digital universe is a term that describes a global human environment saturated with intelligent devices (increasingly, wireless ones) that enhance our ability to collect, process, and distribute information. A key purpose of the book is to stimulate readers to think critically about the pervasiveness of information and communication technologies (ICT) in contemporary societies and how they affect our daily lives. The digital universe that we inhabit is complex and becoming more so as technology evolves and becomes more ubiquitous. “Ubiquity” is a key term that will be used frequently throughout the book – it means to be present in every place, or “omnipresent.” It is often used as part of a commonly cited technology term, “ubiquitous computing,” that describes an environment where computers and intelligent devices are omnipresent. This describes the future of the human environment in societies around the world.

We live in an interesting period in human evolution due to the diffusion of information and communication technologies. The future of machine-assisted communication and related developments in information-processing and artificial intelligence hold great promise for – as well as potential hazards to – human well-being. Information technologies play a central role in when, where, and how we communicate with each other, and their centrality will increase in the future. These technologies are now pervasive in our lives at work and at home, and have blurred the boundaries between these locations to the point where they are often indistinguishable. Digital citizens are connected and “linked in” 24 hours a day – seven days a week. Lewis Mumford made the observation that any widely adopted technology tends to become “invisible” – not in a literal way, but rather in a figurative sense.2 Television and computer displays have become so ubiquitous that we don't think twice about seeing them in classrooms, airports, taverns, and certainly in the workplace. At times on a university campus it appears that everyone has a mobile phone and is busy either texting a friend or talking with them. This would have been a remarkable sight in 1995, but today it is so commonplace that few notice. We are surrounded by telematic devices to a degree that would have been unimaginable in the 20th century, and they will become even more pervasive as they become more powerful and useful in the 21st.3

My hope is that in the process of reading this book you will become a more critical observer of the social use of ICTs, that you will assess the positive and negative consequences of using them, and that you will gain new perspectives in the process that will add richness and depth to your knowledge of human communication and intelligence.

Three Types of Digital Literacy

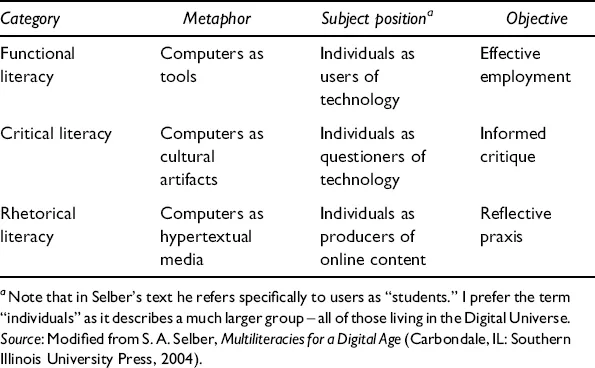

Stuart Selber provides a useful model for computer literacy that we might apply to our study of the digital universe. He defines three distinct types of literacy (see Table 1.1).4 First, people in the teleconnected world should have a functional literacy with computers and software as tools to be used in daily life. In the journalism department at the university where I teach computer-mediated communication, we devote extensive time using expensive hardware (and constantly updated software) to teach prospective journalists and communicators how to use these digital tools. In fact, much of what we term computer education around the world is focused on teaching hardware and software usage. However, Selber makes the astute observation that this type of education provides only one aspect of the literacy that humans need to function in a world filled with digital technologies; digital citizens should also be critically and rhetorically literate.

Table 1.1 Three types of computer literacy.

Becoming Critically Literate

The second category in Selber's model is critical literacy. It assumes the social embeddedness of technology in all networked global societies and highlights the cultural, economic, and political implications of its use. Critically literate users are “questioners of technology” and its applications, and they examine both the positive and negative implications of technology adoption. This is a key theme in this book and an essential aspect of becoming an educated user of technology.

Positive affirmations of information and communication technologies are omnipresent. Hardware manufacturers, software producers, consumer electronics retailers, and the marketing infrastructure that promotes these products and services all ensure that we are aware of their positive attributes. When an innovative information or communication technology is introduced, the advantages are widely touted as part of the marketing campaign. The attributes are often focused on improving the speed of telecommunication, making an information-processing task more efficient, or a combination of these two factors. As consumers adopt these products, the negative consequences are often slow to emerge.

Selber's critical-cultural perspectives of ICT are focused on the examination of hegemonic power relations in society. These perspectives are significant, especially in terms of studying the ramifications of the digital divides that exist between those who have access to information and those who do not. Economic and political perspectives are also useful in studying technology standardization decisions, among other key policy issues. However, I encourage readers to expand their critical perspectives beyond the economic and political to examine fundamental issues of human communication and its automation. For example, how does the mediation of communication (putting a machine in the middle) affect human expression and discourse? Are humans losing a key aspect of the oral communication tradition valued by scholars such as Harold Innis – or has it been repurposed by the mobile phone and the video camcorder? How have communication technologies affected human storytelling traditions and the stories we tell? The critical component of digital literacy is thus focused on the social effects of the use of information and communication technology. It is a rich field of study that encompasses consumer behavior, human psychology, political science, language, philosophy, economics, and human – computer interaction. Some of the most interesting questions about the human use of technology are investigated by social and computer scientists in these fields. In this text we examine the perspectives of critical observers of technology including Harold Innis, Lewis Mumford, Jacques Ellul, Marshall McLuhan, and Bill McKibben.

One of the more perceptive critics of the social use of technology is the late Dr. Neil Postman, a New York University professor, semanticist, and widely read social critic. Postman is the author of Technopoly, an insightful critique of the role that technology plays in advanced information societies.5 His critical perspectives will be addressed in subsequent chapters, but a few key points are relevant here. For Postman and his critical colleagues, knowledge of the history of the development of technology is essential. One cannot predict the future development trajectory of any information or communication technology without understanding its evolution to the present. The history of computing technology is filled with fascinating stories of how “computers” evolved over time from what used to be a human profession to chips found in billions of intelligent devices. While this text is not a comprehensive history of the evolution of ICT from the telegraph to the present day, I have provided the necessary background to comprehend the social context of these technologies and their effects. It is not ironic that studying the history of the evolution of information and communication technology is inherently humanistic. Stories about the development of telegraphy, telephony, television, and the Internet are fundamentally about human creativity, altruism, greed, and ambition. This historical background is presented as needed in a non-linear fashion that you are likely familiar with in locating information online.

Rhetorical Literacy

The third type of digital literacy referenced by Selber is rhetorical literacy. In this context digital technologies are conduits for “hypertextual media” and individuals are viewed as “producers of technology.” This viewpoint describes the world of what is termed Web 2.0 today and Web 3.0 of the near future. We take the power of hypertext and hypermedia for granted in a world where they are found in all online environments. The ability to seamlessly and easily link related content online has transformed the human processing and distribution of information.

The concept of linking information and building webs of knowledge was espoused by Belgian bibliographer Paul Otlet and integrated into his Mundaneum project in Brussels in the early 20th century.6 Additional detail is provided about Otlet and his ideas in Chapter 6; however, an introduction is appropriate in the context of rhetorical literacy. Otlet's vision was to create a massive catalog of all human knowledge and creative work and then provide access to it using electrical communication. An inquiry from a user on any topic would be directed to the Mundaneum in Brussels by telegraph or telephone, where the staff would access millions of index cards (much like a library card catalog of that era) to locate the answer. The return response to the requester was communicated by telegraph or telephone. Otlet's dream in the 1930s was to use a then-new technology known as television to relay the information (with related visuals) back to the requester. His visionary scheme exists online today in the form of Wikipedia, Google, and the Web.

Vannevar Bush in 1945 expanded on Otlet's Mundaneum concept with an idea for an electromechanical system for linking information (both textual and visual) in his Memex.7 The Memex would have recorded and stored information on the then-new medium of microfilm, but the unique concept in Bush's device was a system of switches that would record information about the linkages made between various forms of related content. He termed these linkages “associative trails,” and the concept was a harbinger of what is known today as online hypertext. The flaw...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Some Key Terms

- Part I: Introduction and Framing

- Part II: Internet and Web History

- Part III: Telecommunication and Media Convergence

- Part IV: Internet Control, Cyberculture, and Dystopian Views

- Part V: New Communication Technologies and the Future

- Index