eBook - ePub

Blended Learning

Research Perspectives, Volume 3

Anthony G. Picciano, Charles D. Dziuban, Charles R. Graham, Patsy D. Moskal, Anthony G. Picciano, Charles D. Dziuban, Charles R. Graham, Patsy D. Moskal

This is a test

- 414 pages

- English

- ePUB (adapté aux mobiles)

- Disponible sur iOS et Android

eBook - ePub

Blended Learning

Research Perspectives, Volume 3

Anthony G. Picciano, Charles D. Dziuban, Charles R. Graham, Patsy D. Moskal, Anthony G. Picciano, Charles D. Dziuban, Charles R. Graham, Patsy D. Moskal

Détails du livre

Aperçu du livre

Table des matières

Citations

À propos de ce livre

Blended Learning: Research Perspectives, Volume 3 offers new insights into the state of blended learning, an instructional modality that combines face-to-face and digitally mediated experiences. Education has recently seen remarkable advances in instructional technologies such as adaptive and personalized instruction, virtual learning environments, gaming, analytics, and big data software. This book examines how these and other evolving tools are fueling advances in our schools, colleges, and universities. Original scholarship from education's top thinkers will prepare researchers and learning designers to tackle major issues relating to learning effectiveness, diversity, economies of scale, and beyond.

Foire aux questions

Comment puis-je résilier mon abonnement ?

Il vous suffit de vous rendre dans la section compte dans paramètres et de cliquer sur « Résilier l’abonnement ». C’est aussi simple que cela ! Une fois que vous aurez résilié votre abonnement, il restera actif pour le reste de la période pour laquelle vous avez payé. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Puis-je / comment puis-je télécharger des livres ?

Pour le moment, tous nos livres en format ePub adaptés aux mobiles peuvent être téléchargés via l’application. La plupart de nos PDF sont également disponibles en téléchargement et les autres seront téléchargeables très prochainement. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Quelle est la différence entre les formules tarifaires ?

Les deux abonnements vous donnent un accès complet à la bibliothèque et à toutes les fonctionnalités de Perlego. Les seules différences sont les tarifs ainsi que la période d’abonnement : avec l’abonnement annuel, vous économiserez environ 30 % par rapport à 12 mois d’abonnement mensuel.

Qu’est-ce que Perlego ?

Nous sommes un service d’abonnement à des ouvrages universitaires en ligne, où vous pouvez accéder à toute une bibliothèque pour un prix inférieur à celui d’un seul livre par mois. Avec plus d’un million de livres sur plus de 1 000 sujets, nous avons ce qu’il vous faut ! Découvrez-en plus ici.

Prenez-vous en charge la synthèse vocale ?

Recherchez le symbole Écouter sur votre prochain livre pour voir si vous pouvez l’écouter. L’outil Écouter lit le texte à haute voix pour vous, en surlignant le passage qui est en cours de lecture. Vous pouvez le mettre sur pause, l’accélérer ou le ralentir. Découvrez-en plus ici.

Est-ce que Blended Learning est un PDF/ePUB en ligne ?

Oui, vous pouvez accéder à Blended Learning par Anthony G. Picciano, Charles D. Dziuban, Charles R. Graham, Patsy D. Moskal, Anthony G. Picciano, Charles D. Dziuban, Charles R. Graham, Patsy D. Moskal en format PDF et/ou ePUB ainsi qu’à d’autres livres populaires dans Education et Inclusive Education. Nous disposons de plus d’un million d’ouvrages à découvrir dans notre catalogue.

Informations

Section V

K–12 Perspectives

12

Competencies and Practices for Guiding K–12 Blended Teacher Readiness

DOI: 10.4324/9781003037736-17

The increase in blended teaching (BT) across K–12 contexts is difficult to measure because “blended teaching” is defined and implemented in a variety of ways (Graham, 2013; Hrastinski, 2019). Some define BT as using a combination of both in-person and online modalities (Allen & Seaman, 2010; Garrison & Kanuka, 2004; Graham, 2006), while others include certain pedagogical implications within their definition (Alammary et al., 2014; Bower et al., 2015; Diep et al., 2017; Garrison & Vaughan, 2008; Picciano, 2009; Staker & Horn, 2012; Zacharis, 2015). The most common definition in K–12 contexts is part of this latter category, describing BT as “at least in part through online delivery, with some element of student control over time, place, path and/or pace” (Horn & Staker, 2011, p. 3). Watson and Murin (2014) also require some student control over “time/pace/path/place,” adding that blended learning (BL) “changes the instructional model away from one-to-many (teacher-to-students) instruction and toward a personalized, data-driven approach” (p. 13). These definitions describe personalization as essential to BT. While some effective blends have aspects of personalization, such pedagogy is not essential to creating a blend (Arnesen et al., 2019). Measuring K–12 implementation of BL is difficult due to definitional murkiness and because implementation can happen at the school level, be led by individual teachers, or remain within individual classrooms (Graham, 2019).

We define BT competencies as the knowledge, skills, and abilities that teachers need to teach in BL contexts, building from competencies presented in K–12 Blended Learning: A Guide to Personalized Learning and Online Integration (Graham, Borup, Short et al., 2019). These competencies approach BL in the broadest sense, as an umbrella term for any combination of both online and in-person instruction (Graham, 2013, 2019), and are therefore pedagogically agnostic. Regardless of chosen pedagogies, BT requires a significant paradigm shift for teachers as it differs from the traditional teaching methods many experienced as students and have been trained to use as pre-service and in-service teachers (Greene & Hale, 2017). Various sources have identified or suggested competencies necessary for BT but have not evaluated them in terms of prevalence in practice. Pulham and Graham (2018) reviewed 17 documents with K–12 BT competencies and synthesized six competency areas for BT. Subsequently, Pulham et al. (2018) found that many of the individual competencies identified were not specific to BT contexts.

There are pedagogical implications for understanding and identifying the most influential BT competencies. Greene and Hale (2017) called for pre- service and in-service training for blended and online teaching, explaining that twenty-first-century teachers may be expected to “facilitate learning that lives up to the potential of both modes of education” (p. 147). As BL becomes more prevalent, teacher preparation programs need to prepare novice teachers for BT. Pre-service curriculum will need to include competencies specific to blended pedagogy because generic teaching competencies do not capture all the skills necessary for BT (Pulham et al., 2018). Identifying competency areas that are relevant to BT in K–12 contexts will help teacher educators know what to emphasize in their pre-service training and how to assist in-service teachers, administrators, and professional development leaders as they transition traditional, in-person classes to blended classes.

Literature Review

As demand for BL increases (Barbour, 2017), understanding the relative prevalence of BT competencies becomes more urgent (Dziuban et al., 2018; Eisenbach, 2016). Researchers have demonstrated that skills and practices associated with BT are not the same as those needed for in-person or online teaching (Pulham et al., 2018; Graham, Borup, Short et al., 2019). Based on frameworks presented in literature, BT is not simply the addition of technology to the classroom (Archambault et al., 2014; Bjekic et al., 2010; Oliver & Stallings, 2014). Yet most PD programs targeting BL focus on technology tools instead of blended competencies (Graham, Borup, Pulham et al., 2019). Since the competencies associated with BT vary so dramatically from those of other forms of teaching, blended education requires a more deliberate and specific emphasis on professional development (Eisenbach, 2016; Ojaleye & Awofala, 2018; Pulham et al., 2018).

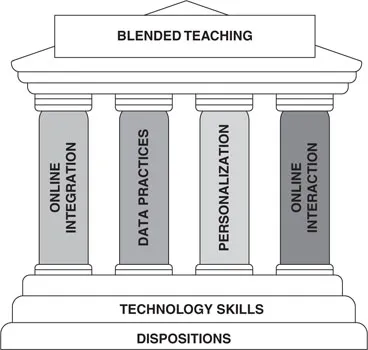

Many researchers have identified specific competencies to improve educators’ successful implementation of BL (Akarawang et al., 2015; Anthony, 2019; Bjekic et al., 2010; Oliver & Stallings, 2014; Pulham & Graham, 2018). Pulham and Graham (2018) identified eight pre-service teacher competency areas for online and blended learning. Graham, Borup, Pulham et al. (2019) built on this research, creating a rigorously validated framework with 13 competency areas, through which teachers could assess their readiness to start blending. Graham, Borup, Short et al. (2019) refined this work in their guide to BT with a framework consisting of foundational dispositions and technology skills, with four competency areas: online integration, data practices, personalization, and online interaction (Figure 12.1). These competency areas were used to direct the research presented in this chapter.

Figure 12.1 Blended Teaching Competency Framework

Source: (Graham, Borup, Short et al., 2019)

Research Questions

This research sought to connect the competency areas from Graham, Borup, Short et al. (2019) to current K–12 BT practices by answering the following questions:

- How do proposed BT competency areas relate to actual K–12 BT pedagogical practices?

- What examples can be found of quality BT practices within the competency areas of online integration, data practices, personalization, and online interaction?

- What areas for potential growth for experienced K–12 blended teachers are revealed by investigation of BT competency areas?

Methods

We answered these questions by implementing two separate though related methodologies. First, we analyzed BT artifacts to establish the prevalence of proposed competency areas in BT practices. Second, we analyzed interviews of teachers with BT experience to uncover examples of effective established practices as well as practices needing further development within each competency area.

Artifact Analysis

The artifacts included 959 observations, interviews, and videos created by the Learning Accelerator, a non-profit group dedicated to connecting K–12 blended practitioners to the knowledge, tools, and networks needed to effectively blend and personalize instruction. The artifacts were collected from over a dozen K–12 districts and span all grade levels. BT competencies from Graham, Borup, Short et al. (2019) were used as a priori codes to analyze the artifacts. We completed independent coding of 372 randomly sampled artifacts, allowing for generalizability to all artifacts with a confidence level of 95% (+/-4%).

Interview Analysis

We identified prospective participants for the interviews through working relationships, recommendations from district-level leaders, recruitment at various conferences, and professional partnerships such as the Learning Accelerator, the Clayton Christensen Institute, and the Digital Learning Collaborative. We requested interviews from strong candidates through email and asked other candidates to fill out a survey designed to vet participants not selected for the first round of interviews. Survey respondents indicating BT experience received additional interview invitations. Participants were located domestically and from various content areas: English language arts, social studies, math, science, computer science, visual and performing arts, and others (see Table 12.1). Their teaching experience ranged from 2 to 20 or more years, and each teacher had at least 1 year of BT experience.

| Number of interviews | Grade levels | Subjects |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | K-3 | General |

| 3 | 4–6 | General |

| 3 | 7–12 | Humanities (language arts, foreign languages) |

| 3 | 7–12 | Social sciences (social studies, history) |

| 3 | 7–12 | STEM (science, engineering, math) |

| 3 | 7–12 | Arts (visual arts, performing arts, music) |

| 3 | 7–12 | Other (physical education, health, FACS, special education) |

When candidates agreed to participate, they signed an informed consent form and scheduled an interview. We conducted semi-structured interviews, lasting approximately 90 minutes, using a video conferencing platform that automatically generates transcriptions. We designed the interview protocol to explore participants’ implementation of the four competency areas identified by Graham, Borup, Short et al. (2019). Research assistants prepared and anonymized the video transcriptions, which we uploaded to NVivo for coding using a thematic analys...

Table des matières

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- About the Editors

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Section I Introduction and Foundations

- Section II Student Outcomes

- Section III Faculty Issues

- Section IV Adaptive Learning Research

- Section V K–12 Perspectives

- Section VI International Perspectives

- Section ViI Science and Health Research

- The Future

- Index

Normes de citation pour Blended Learning

APA 6 Citation

[author missing]. (2021). Blended Learning (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2826449/blended-learning-research-perspectives-volume-3-pdf (Original work published 2021)

Chicago Citation

[author missing]. (2021) 2021. Blended Learning. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/2826449/blended-learning-research-perspectives-volume-3-pdf.

Harvard Citation

[author missing] (2021) Blended Learning. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2826449/blended-learning-research-perspectives-volume-3-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

[author missing]. Blended Learning. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2021. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.