Geography

Sustainable Urban Transport

Sustainable urban transport refers to transportation systems and infrastructure designed to minimize environmental impact, promote public health, and support social equity within urban areas. This includes initiatives such as public transit, cycling infrastructure, pedestrian-friendly urban design, and the use of clean energy vehicles. The goal is to create efficient, accessible, and environmentally friendly transportation options for urban residents.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

Related key terms

1 of 4

Related key terms

1 of 3

12 Key excerpts on "Sustainable Urban Transport"

- eBook - ePub

- V. Kelly Turner, David H. Kaplan, V. Kelly Turner, David H. Kaplan(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The focus of this review is the sustainability of transportation in the urban context. Transportation is intertwined with many aspects of urban geography and planning, especially when considering sustainability. The Brundtland Commission (1987) defined sustainable development as development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” (p. 8). Although the term “sustainability” was rarely used in urban transportation and urban geography until the early 1990s (Purvis & Grainger, 2004), concerns over the development of transportation systems and their associated impacts on urban form, air quality, and society go back over a century (Alonso, Monzón, & Cascajo, 2015; Carroll & Bovls, 1957; Dickinson, 1949; Kidd, 1992; Marble, 1959; Pratt, 1911; Stradling & Thorsheim, 1999; Taylor, 1915).Urban transport systems today are largely motorized, dependent on nonrenewable fossil fuels (Black, 2010). Emissions from vehicles contribute significantly to both climate change and the degradation of urban air quality (Chapman, 2007; U.N. Habitat, 2016). Traffic congestion causes substantial economic losses in wasted time and fuel (Downs, 2005). The geographic organization of land use and transport infrastructure in our cities can promote social equity (Curtis, 2008; Van Wee & Handy, 2016) or lead to social exclusion for disadvantaged groups (El-Geneidy et al., 2016; Lucas, Van Wee, & Maat, 2016; Manaugh & El-Geneidy, 2012). New research has begun to show that transport systems affect our happiness (Pfeiffer & Cloutier, 2016) and overall quality of life (Bäckström, Sandow, & Westerlund, 2016; Bergstad et al., 2011; Friman, Fujii, Ettema, Gärling, & Olsson, 2013).This paper reviews the literature on urban transportation sustainability using three frameworks. First, the goals of transportation sustainability are summarized in three fundamental “pillars” of environmental, social, and economic quality (Gudmundsson, Hall, Marsden, & Zietsman, 2016). The unsustainability of urban transportation systems can also be understood via these three pillars. Second, the literature on sustainable transport solutions is often divided into narrow and broad approaches (Litman & Burwell, 2006), as summarized in Figure 1. - eBook - ePub

Advancement in Oxygenated Fuels for Sustainable Development

Feedstocks and Precursors for Catalysts Synthesis

- Niraj Kumar, Kaliyan Mathiyazhagan, V. Raja Sreedharan, Abul Kalam(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Elsevier(Publisher)

Vianna and Machado (2016) in Rio de Janeiro emphasizes that the value that people waste traveling to and from work can be invested in energy efficiency and its currency value, which is about $35.7 billion in 2014. This amount is related to 8.1% of region’s gross domestic product (GDP).In the United States, about $160 billion is lost as a result of traffic and transportation problems, which is about 1% of GDP. This percentage has remained stable over the past few years. Kennedy et al. (2005) stated that achieving a sustainable transportation system requires the following conditions: (1) the existence of an unqualified structure for land use and transportation management, (2) access to an impartial and efficient financial system and investment, (3) strategic development of infrastructure and special attention to local projects. However, even a vast network of subway lines could not meet the needs of all urban areas. Although a subway system provides faster and better services, it does not have the capacity to meet all the needs of a modern city. As a result, different cities developed different rail systems, including tramways, light rail transit, subways, and regional railway. In the field of urban transportation systems, they have a decisive role in the pursuit of sustainable development in our communities. In fact, as Banister (2008) states, sustainable transportation plays an important role in the future of sustainable cities. To achieve the paradigm of sustainable mobility, certain conditions must be created. Numerous studies have focused on the fact that public transportation systems in the urban context can be considered as dynamic and problem-solving systems. However, values and motivations are important in tackling environmental issues with a sustainable consumption approach, and this requires raising awareness and changing consumer behavior.The rest of the chapter is organized follow as: the goals of sustainable development are explained in Section 10.2 . Section 10.3 explains the perspective of essential and long-term sustainable planning. The role of behavior in transportation and the external effects and motivations in using personal vehicles are investigated in Sections 10.4 and 10.5 , respectively. Section 10.6 discusses transportation and sustainable development. The finds of the chapter are explained in Section 10.7 . Finally, Section 10.8 - eBook - ePub

- Ole B. Jensen, Claus Lassen, Vincent Kaufmann, Malene Freudendal-Pedersen, Ida Sofie Gøtzsche Lange, Ole B. Jensen, Claus Lassen, Vincent Kaufmann, Malene Freudendal-Pedersen, Ida Sofie Gøtzsche Lange(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

2 emissions and land consumption are to be achieved. In light of the Brundtland Commission’s above-mentioned definition of sustainable development, the phrase about ‘a vibrant economy’ should arguably be replaced by the formulation ‘an economy meeting the population’s essential needs’.On this background, I propose a definition of sustainable mobility largely based on the CfST definition, but structured in such a way that the economic (to meet human needs), environmental (protection of natural resources and ecosystems) and social (equity within and between generations) dimensions of sustainable development are mentioned under a bullet each:Sustainable mobility is mobility in accordance with the principles of sustainable development, understood as a volume of physical mobility and a transport system where mobility in society- allows the basic mobility needs of individuals and societies to be met safely and consistent with human health, offers choice among environmentally sustainable transport modes, operates efficiently and supports an economy meeting the population’s essential needs

- takes care of ecosystem integrity and limits emissions and waste within the planet’s ability to absorb them, minimizes consumption of non-renewable resources, limits consumption of renewable resources to the sustainable yield level, reuses and recycles its components, and minimizes the use of land and the production of noise

- is affordable and consistent with equity both within and between generations, at a global, regional as well as local scale.

Strategies for obtaining sustainable mobility

Below, different strategies for achieving sustainable mobility will be discussed. While the focus of this book is on urban contexts, the discussion below will not be limited to intra-urban travel, since interactional mechanisms may exist between daily-life travel and long-distance leisure travel. - eBook - ePub

- Bernard Favre(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Wiley-ISTE(Publisher)

The requirements linked to transport security are also proving to be strongly “dimensioning”: the ability of an organization or a transport system to prevent the risk of deliberate malevolence, or to reduce its effects, must be strengthened. Under certain circumstances, transport is targeted by actions that aim to harm the integrity of users, workers, carried goods and resident populations. Some striking examples can be recalled (such as the infamous 9/11 attack in 2001).Figure 1.1 shows a synthesis of the ingredients for transport, which appears in multidimensional form: elements in the context of societal, economic or technical order (in italics), challenges and objectives (framed), the “{mobility–productivity}, {environment–productivity}, {safety–security}” trio, to which the systemic anthropocentric “man and cooperative systems” is added, the latter being represented by a circle that symbolizes the interface with other associated systems (energy, materials, intelligence, etc.). However, man remains at the center of sustainable transport.Figure 1.1. Ingredients for sustainable transport. Context and challenges [FAV 07]1.2. Towns, territories and sustainable transport

Transport is to territory what blood is to living organisms: a vital function to supply and drain the territory, to move “nutrients” around, and to evacuate “waste”, which enables it to exist and develop harmoniously with the various systems that form its economic, social and environmental aspects.More than half of the world’s population already lives in cities and the trend will continue for the foreseeable future, particularly with the further emergence of “mega-cities” (23 towns with more than 10 million inhabitants in 2012).Improving urban mobility is one of the points included in the agenda of all governing bodies, from a local level to a global level: transport within towns to guarantee the movement of inhabitants for their daily activities, transport on the outskirts of these towns to link living and working zones, connecting these towns by intercity transport means to connect them to each other or to guarantee the supply of base materials and consumable goods, etc. The need for transport is therefore essentially associated with towns, which have both a systemic organization and uses it to impose the best possible integration of their transport systems into the urban structure. However, the provision and maintenance of infrastructure for transport, its operation, as well as programming and developing new infrastructure, are at the heart of political debates on the management of towns. They need areas of land in addition to financial resources and are in constant competition with the other main elements of urban fabric. The same holds true for the operation of infrastructures and the management of vehicles associated with them, particularly in terms of gas and noise emissions, congestion and safety. The development of public transport is also one of the main topics of urban politics. Strengthening the governance of transport systems in urban areas is perceived by public entities as an inescapable requirement for the sustainable development of towns, from economic, social and environmental points of view. Guaranteeing adequate needs for mobility and promoting transport solutions between public and private spheres have also been considered. In order to do this, initiatives to form partnerships have been encouraged. They can lead to regulations for the use of infrastructures serving urban territories. They can also put forward the development of integrated solutions for transport systems within urban systems, by handling vehicles, infrastructure, operators and operational rules in a coordinated manner. Public policies play a major role in steering the choice of the favored transport mode, investments, by controlling through regulations or promoting good practices. They must also arbitrate between a variety of constraints, of actors and of expectations. Private entities develop solutions for the transport market. They encourage innovations in the fields of energy, intelligence and materials. The evolution of technologies and services regularly provides pertinent solutions for urban transport, although they are used differently depending on the urban agglomeration and according to the region of the world being considered16 - eBook - ePub

Urban Social Sustainability

Theory, Policy and Practice

- M. Shirazi, Ramin Keivani(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

4 Social sustainability and transportMaking ‘smart mobility’ socially sustainable

Tanu Priya Uteng, Yamini Jain Singh, and Oddrun Helen Hagen

Social sustainability in the transport planning sector

The ethos of numbers and technocratic rationality overpowers other areas in transport-related development projects. Often expressed in ‘kilometres of roads constructed’, ‘numbers of new highways built’ in the past fiscal year, ‘time savings’ etc., the engineering and technical dimension routinely takes precedence. The essential denominator of development, i.e. the affected population, is given a backseat in a typical transport discourse and (aggregated) population ends up as mere numbers to be fed into the transport modelling exercises, typically projecting the need for capacity enhancement of road systems or mass transit systems. In this number-crunching exercise, only one pillar of sustainable development has historically been given priority – economic development. Increasing environmental awareness has led to altering this pattern by focusing on the goal of environmental protection along with economic efficiency. Despite this, the ways in which these ‘calculated and projected’ environmental and economic developments filter down to affect the general populace or the pillar of social sustainability remain largely ignored.For example, sieving through published works by the Transportation Research Board on sustainable transportation till 2014 suggests that the three thematic areas of sustainability (economic, environmental, social) are not equally represented in the transportation literature. Even though the term ‘sustainability’ surfaced only in 1980s, and research on the three themes of sustainability actually started to appear after the 1990s, research focus on economic and environmental sustainability is visible. Lineburg (2016: 11) plots the occurrence of each sustainability sector in the transportation literature till 2014 and highlights that environmental sustainability has had more attention in recent times than economic and social sustainability because there was high awareness of environmental crisis brought about through the use of fossil fuels in the transport sector. As noted by Jeekel (2017), the attention on social issues, although considered important in reaching sustainable development goals, lagged behind in both practice and research arenas. The topic of social sustainability, therefore, demands further study through bringing together ‘the relationships between individual actions and the created environment, or the interconnections between individual life-chances and institutional structures’ (Jarvis et al - eBook - ePub

State of the World 2012

Moving Toward Sustainable Prosperity

- The The Worldwatch Institute(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Island Press(Publisher)

3 Table 4–1. Characteristics of Unmanaged Motorization and Sustainable TransportThe Arc of Sustainable Transport in International Agreements

The sustainability challenges facing individual cities and communities—from economic development to climate change—are challenges that are global in scope. They require a framework of commitment at the international level in order to provide incentives for global participation, support global initiatives, and monitor global progress toward goals. In 1992, Agenda 21 considered transportation a key program area for both resource management and for “improving the social, economic and environmental quality of human settlements.” It even went so far as to specifically call for efficient and cost-effective approaches such as integrated land use and transportation planning, high-occupancy public transport, safe cycleways and footpaths, international information exchange, and a reevaluation of present consumption and production patterns. Although transport was featured prominently, however, and even discussed in some depth, no targets, goals, commitments, or other forms of accountability were incorporated.The Kyoto Protocol adopted by 191 countries since 1997 established legally binding targets for an average reduction of 5 percent of global greenhouse gases relative to 1990 emissions by 2012. With its focus on using markets to find least-cost GHG reduction strategies, it avoided sectoral strategies and did not specifically mention transportation. The climate finance mechanisms it endorsed—the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM)— were designed primarily around the energy sector, where relatively accurate GHG accounting requires fewer data and is easier to estimate than in the transportation sector. This led to underfunding of sustainable transport projects. While the transport sector now accounts for 27 percent of energy-related GHGs, these climate change mitigation funds have disbursed less than 10 percent of their funding to it.4 - C. Michael Hall, Stefan Gossling, Daniel Scott, C. Michael Hall, Stefan Gossling, Daniel Scott(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

2011 : 14).Sustainable mobility: a changing concept

There is, however, as yet no political or scientific agreement on a definition of sustainable mobility. Rather, the concept’s focus has, to an increasing extent, reflected socially desirable attributes of local- and project-level problems. A diversity of definitions and interpretations of the concept has been presented; the risk, therefore, is that the concept will become mere rhetoric and of little value in guiding policy makers and scientists. Examples of issues dealt with by these and other studies include: protecting wildlife and natural habitats, reducing noise levels, promoting economic growth, facilitating education and public participation, reducing congestion levels, minimizing accidents and fatalities, ensuring stakeholder satisfaction, enhancing aesthetic dimensions of neighbourhoods, supporting cultural activities, increasing tourism’s contribution to GDP, promoting liveable streets and neighbourhoods, and minimizing transport-related crime.A review shows that the focus of mainstream literature about sustainable mobility indeed has changed during the last two decades (Holden 2007). Sustainable passenger transport problems are being addressed in new ways by researchers representing an increasing number of scientific disciplines applying different methodological approaches (Black & Nijkamp 2002 ). The concept’s definition has changed to include a broader set of passenger transport types like production travel, reproduction travel (e.g. Shiftan et al. 2003 ; Castillo & Pitfield 2010 ; Amekudzi et al. 2009 ; Banister 2011 ), and leisure-time travel (e.g. Black & Nijkamp 2002 ; Mokhtarian 2005 ; Ory & Mokhtarian 2005 ; Næss 2006 ; Banister 2008 ; Holden & Linnerud 2011 ). Vilhelmson (1990- eBook - ePub

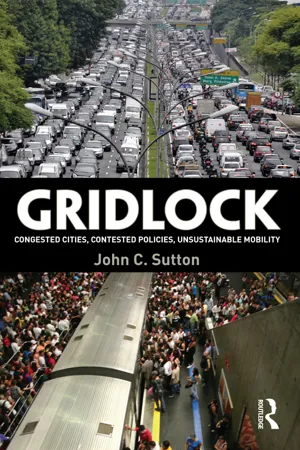

Gridlock

Congested Cities, Contested Policies, Unsustainable Mobility

- John Sutton(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Pahl 1965 ). The city archetypes therefore may only serve as historical exemplars of the relationship between traffic and city structure. Clearly the preservation of cities with a strong core and viable public transport service requires strong planning policies that not all countries have or want. Even with strong planning policies it may not be possible to achieve the desired transportation–land use balance. The centripetal force of information and communication technology, leading to disparate neighbourhoods and aspatial communities of interest, is counterweight to the central places model of urban development. In contemporary society the ‘push’ of meta-mobility appears to be a greater force than the ‘pull’ of accessibility in shaping location and movement patterns.2.3Balancing Mobility and SustainabilityAccording to the Brundtland Report, Our Common Future, sustainable development is ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development 1987 , p. 43). It is generally recognised that current transport systems are not sustainable because they are dependent on fossil fuels, which are not only finite but emit greenhouse gases that cause global warming, produce excessive numbers of accidents (fatalities and injuries) and create congestion that borders on gridlock. The challenge is how to balance the demand for mobility against the need for sustainable transport. This is not easy because the measures to deliver sustainability imply restrictions on mobility – using ‘carrots’ and ‘sticks’ – that is at odds with a society in which ease of mobility is a key motivator in the travel behaviour of people and businesses.Physical mobility is simply the ability to move from one place to another by whatever means are available, which could be by different modes such as walking, cycling, bus, train, car or plane. Most trips involve multimodal legs, such as walking to the bus stop or to the car park and ride at train stations, taking a taxi to the airport and so forth. More mobile societies, principally developed economies, make greater use of mechanised modes of travel, which enable longer distances to be covered in a given time. Thus mobility is synonymous with travel speed and distance, and a common measure of mobility among nations is the number of vehicle miles (or kilometres) of travel per capita. Richer countries generally travel further, even if the time spent travelling is similar to that in poorer countries. Advanced economies have become dependent on mechanised modes of travel to transport large volumes of passengers and freight. - eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Sustainable Transportation

Policy, Planning and Implementation

- Preston L Schiller, Jeffrey Kenworthy(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

(Mumford 1961, p. 512)Urban design and sustainable transportation

Why is urban design important in sustainable transportation, building healthy and green communities and combating the urban heat island effect and climate change? Through authors and practitioners such as Bentley et al. (1985), Gehl (1987, 2010) and Gehl and Gemzøe (2000, 2004), urban design today is concerned with factors that either directly or indirectly seek to limit car-based design and planning. The main objectives in this theory and practice are to promote walkability, cycling and greater use of transit, beautify and humanize the public realm and facilitate the development of healthier communities.The physical design and elements of urban fabrics certainly play a clear and undeniable role in fostering more Sustainable Urban Transportation and the work of Jan Gehl and his associates in many cities around the world gives ample evidence of this (e.g. Gehl et al. 2004, 2009). Some of these changes include radical increases in residential development in central cities, widening of sidewalks, pedestrian and transit-priority streets, greening of streets, huge increases in local shopping and cafes and accompanying massive increases in pedestrian flows and public life. All these effects can be physically measured, monitored, quantified and correlated over time.Socially and psychologically healthier communities are a little more difficult to define, characterize and measure and it is even more difficult to claim any cause and effect relation ships between them and urban design or physical planning measures. One cannot assert any simple physical determinism in the creation of socially healthier urban communities. The existence of socially healthy communities, or the lack therefore, is mediated by a plethora of social and cultural norms and at least partly shaped by history, the forces and factors that have collectively helped to make a community what it is today. However, it can also be argued that these cultural norms and behaviors, which are shaped over centuries, have in turn been influenced by the types of cities people have lived in, especially the structure and quality of the public realm and whether it supports or does not support closer ties and relationships between locals and strangers alike (see later discussion of urban fabrics theory). - eBook - ePub

Sustainable Urban Design

An Environmental Approach

- Adam Ritchie, Randall Thomas, Adam Ritchie, Randall Thomas(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Taylor & Francis(Publisher)

Part One Sustainable Urban Design ConceptsPassage contains an image

1 Introduction

Adam RitchieDOI: 10.4324/9781315787497-1Sustainability

Sustainability is about poetry, optimism and delight. Energy, C02 , water and wastes are secondary. The unquantifiable is at least as important as the quantifiable; according to Louis Kahn, ‘the measurable is only a servant of the unmeasurable’1 and ideally the two would be developed together. Using a term coined by the eighteenth-century author Jonathan Swift, this is a modest proposal.This book identifies the major issues in making cities environmentally sustainable. By the time you are reading this sentence, we will, for the first time in history, have reached a milestone when more than half the world’s population, 3.3 billion people, are living in urban areas.2 Cities offer tremendous opportunities for community, employment, excitement and interest, which attract many of us. They can also create problems of congestion, noise and pollution which repel many others, or at least those who have the choice. These problems can be addressed, in part, through design, but success depends on recognising trade-offs and getting the balance right.It is vital that we evolve towards sustainability in urban form, transport, landscape, buildings, energy supply, and all the other aspects of vibrant city living. Part of this will involve making cities more suitable for people, and therefore moving away from the previous policy of cities being for cars. Creating streets for pedestrians, cyclists and public transport is a key aspect of sustainable development.Cities must also become greener for the sake of the diversity of many species (as well as humans) who inhabit them. Nature’s ecosystem, with its robust and stable systems, is one model for future cities. However, in addition to an ecosystem’s variety, diversity, redundancy and richness, we need poetry, whimsicalness, playfulness and excitement. Aristotle’s view was that a city should be designed to make its people secure and happy.3 - Jean Mercier, Fanny Tremblay-Racicot, Mario Carrier, Fábio Duarte(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Pivot(Publisher)

© The Author(s) 2019Begin AbstractGovernance and Sustainable Urban Transport in the Americas https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99091-0_2Jean Mercier ,Fanny Tremblay-Racicot ,Mario Carrier andFábio Duarte2. The Context of Sustainable Urban Transport

Jean Mercier1,Fanny Tremblay-Racicot2,Mario Carrier3andFábio Duarte4(1) Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada(2) École nationale d’administration publique, Québec, QC, Canada(3) Université Laval, Québec, QC, Canada(4) Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USAAbstract

In this chapter, the authors look at the three main challenges that cities and metropolitan areas face in dealing with the challenge of sustainable transport. In the context of increasing liberal values and privatization policies, they face a planning challenge, at a time when government intervention is seen as lacking in efficiency. Second, the cities face an extending urban landscape, with a fragmenting spatial configuration that is not conducive to public transport. Third, cities face a public policy challenge, due to the fact that an increasing variety and number of stakeholders demand that their point of view be heard and considered. Drawing from public policy and political studies literature, Mercier and his colleagues then identify two policy configurations to deal with these challenges, the government (more top-down) mode, and the governance (more horizontal, participative) mode. Building on the differences between these two styles of public policy, the authors then propose a model of policy instruments which can be helpful in ascertaining the contribution of these two policy configuration in attaining Sustainable Urban Transport.- eBook - ePub

The Green City

Sustainable Homes, Sustainable Suburbs

- Nicholas Low, Brendon Gleeson, Ray Green, Darko Radovic(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Total freedom for the car makes walking a difficult experience. It is also self–defeating, because each individual who exercises his/her personal freedom interferes with the freedom of everyone else, simply by occupying a large amount of what is limited space on the road. And now we have colossal freeways attracting so many journeys that they become jammed. With more and better roads, congestion has not diminished; it has increased. Road transport is today the fastest–growing contributor to greenhouse emissions in Australia, and in most Western countries. Sustainable transport for the green city requires a more conscious attempt at planned compromise – at making the best possible trade–off between freedom of movement and the other qualities desired for the green cityJust as important as the physical system (the network of lines, routes and roads) is the system by which transport is planned, managed, supplied and funded. And yet when it comes to planning, there is often no system in the real sense of the word: a co–ordinated, integrative mechanism for ensuring urban accessibility Strangely enough, co–ordinated planning of a whole transport system, including walking and cycling as well as roads, motor vehicles and public transport, is quite rare almost everywhere in the world.The green city will have a transport system in which there is a network of paths connecting people safely on foot with the places they want to reach from home or from public transport terminals. Space in city centres will be allocated to transport with the primary aim of creating a good environment for human occupation, meaning that a high priority will be given to non–motorised movement. In most suburbs a mixture of workplaces and homes will be provided to increase opportunities for people to live near where they work. People living in green cities will have the benefit of public transport systems that offer a frequent and regular service throughout the city from early morning to late at night, throughout the week and at weekends. Travel on public transport will be fast, and change of mode – changing trains, trams or buses – will be minimised, but where it occurs it will be quick, safe and easy When people use cars, they will travel in fuel–efficient vehicles emitting not only very little poisonous gas but also little carbon dioxide. Effective demand management will reduce the number of compulsory trips. The priority, in terms of transport system planning, will be foot travel, then cycling, then public transport and finally private motor vehicles.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.

Explore more topic indexes

Explore more topic indexes

1 of 6

Explore more topic indexes

1 of 4