History

Heian Period

The Heian Period in Japan, lasting from 794 to 1185, was characterized by a flourishing of art, literature, and culture. It was a time of peace and stability, during which the imperial court in Kyoto became the center of political and cultural life. The period is known for the development of classical Japanese literature, including the famous novel "The Tale of Genji."

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Heian Period"

- eBook - PDF

Japan

History and Culture from Classical to Cool

- Nancy K. Stalker(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

50 The Heian Period, from 794 to 1185 , is named for the new imperial capital established at Heian-kyo – (later called Kyoto). That city would remain the imperial capital of Japan until 1868 , when the young Meiji emperor moved his court to Tokyo to stand at the head of a new system of government and a new nation-state. Heian is known as Japan’s classical period, a time when aesthetics and court culture attained a high degree of refinement. Around the year 1000 , there was a flowering of distinctively Japanese aristocratic culture centering on the court, while imported Chinese cultural practices, from poetry to geomancy, also continued. It was an age of great creativity in literature, the arts, and religion. The lives of Heian elites were filled with aesthetic cultural practices. Cloistered and idle in the capital city, courtiers obsessed over their appearance, love affairs, cultural pastimes, and ceremonial rites. This chapter focuses on such activities among the aristocracy. It is important, however, to remember that these elites constituted only a small minority, numbering sev-eral thousand men and women in a population of around 5.5 million persons. The rich written record of courtly life—including diaries, poetry, and novels produced by noblemen and noblewomen—describes a lifestyle that no mem-ber of the lower classes could dream of attaining. political and social developments In early Heian, courtiers and aristocrats, led by vigorous emperors, contin-ued to actively assimilate Chinese administrative and cultural models introduced under Nara-era reforms. Emperor Kammu ( 737–806 ) moved the capital from Nara to Heian-kyo – in 794 in order to escape the influence of powerful Buddhist monastic institutions and to locate the palace closer to his allies, powerful clans of immigrants from the Korean Peninsula. Kammu 3 The Rule of Taste Lives of Heian Aristocrats, 794–1185 map 4 . Kyoto, formerly known as Heian-kyo – , in 1696 . - eBook - PDF

- Haruo Shirane, Tomi Suzuki, David Lurie(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

p a r t i i * THE Heian Period ( 794 – 1185 ) 7 Introduction: court culture, women, and the rise of vernacular literature h a r u o s h i r a n e In the four hundred years from the end of the eighth century to the end of the twelfth century, the center of political power was located in the Heian capital (today known as Kyoto), from which the period takes its name. The political origin of the Heian Period can be traced to 781, when Emperor Kanmu (r. 781–806) ascended the throne. Three years later (in 784), he moved the capital from Heijo ¯ (Nara) about thirty kilometers northwest, to Nagaoka, and then in 794 to Heian, nearby to the northeast of Nagaoka. The end of the Heian Period is usually considered to be 1185, when the Taira (Heike), a military clan, was demolished and Minamoto Yoritomo (1147–99), the leader of the Minamoto (Genji) military clan, established the Kamakura bakufu (military government) in eastern Japan. At the end of the eighth century, the aristocratic clans that had controlled the ritsuryo ¯ state during the Nara period were gradually supplanted. By the mid ninth century the ranks of the nobility (kugyo ¯ ) were dominated by the Fujiwara and Minamoto (Genji). Among them, the northern branch of the Fujiwara eventually prevailed, and in the mid-Heian Period, beginning in the latter half of the tenth century, controlled the throne through the sekkan (regent) system. By marrying their daughters to emperors, the Fujiwara became the grandfathers of future emperors, placing them in the position to be regents who ruled in place of the child emperor. A parallel office gave them similar privileges during the reigns of adult emperors. During the late ninth century, Emperor Uda (r. 887–97), with the aid of Sugawara no Michizane (845–903), managed to hold off the Fujiwara. Uda’s son Emperor Daigo (r. 897–930), with the assistance of Michizane and the minister of the left, Fujiwara no Tokihira, similarly attempted to restore direct imperial rule. - eBook - PDF

- William M. Tsutsui(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

The conference was composed of five separate panels of three to four papers each, a total of sixteen papers on various aspects of Heian political, institutional, reli-gious, literary, and artistic history. The focus was on the first three centuries of the era, especially the mid-Heian Period, or what corresponds to the early royal court state. Each panel, indeed each paper, attempted to wrestle with the interplay between center and periphery in order to provide some balance to the previously overwhelming concentration upon central issues and institutions. Thus issues – such as cross-border traffic in Kyu ¯shu ¯, temple networks in the provinces, provincial rebellion, Chinese traders and their impact on the nobility, the life of commoners in the provinces, and Fujiwara no Michinaga’s connection to provincial governors – were for the first time addressed by non-Japanese scholars, or by Japanese scholars in English. The forthcoming publication of this volume will certainly bring the study of the Heian Period to a new level and hopefully attract the interest of future researchers. Despite the importance of the Cambridge History volume and the forthcoming Centers and Peripheries , there is a great deal of work to do before English language coverage of the Heian Period is fully adequate. Although it would be nonsensical even to suggest that the situation could ever approach the coverage Heian enjoys in Japan, still, non-Japanese works fall woefully behind not only in volume, but also in areas of coverage. Needless to say, interest in Heian political and economic institutions is far THE Heian Period 43 less well developed than that in literature and art, and even Heian religion. Thus while we are still looking for adequate historical narratives, there are excellent translations into English of virtually all the major works of Heian literature (indeed, translations of The Tale of Genji compete with one another for course adoption!). - eBook - PDF

- Conrad Schirokauer, David Lurie, Suzanne Gay, , Conrad Schirokauer, David Lurie, Suzanne Gay(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

The Visual Arts For the purposes of art history, the Heian Period is readily divided into two parts. “Early Heian,” sometimes called the Ko ¯ nin or Jo ¯ gan Period, designates roughly the first century in Kyoto (794–897). In architecture, a transformation of taste is Copyright 201 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. Chapter 3 ■ The Heian Period 63 apparent in a variety of forms. It is particularly notable in the layout of the new temples, because when Saicho ¯ and Ku ¯ kai turned from the Nara Plain to build their monaster-ies in the mountains, they aban-doned the symmetric temple plans used around Nara. Down on the plain, architecture could afford to ignore the terrain; but in the moun-tains, temple styles and layouts had to accommodate themselves to the physical features of the site. On Mount Hiei and elsewhere, the nat-ural setting, rock outcroppings, and trees became integral parts of the temple, as had long been the case with shrines devoted to kami. Even on Mount Ko ¯ ya, where there was enough space to build a Nara-style temple complex, the traditional plans were abandoned. Changes were also made in building materials and decoration. During the Nara Period, the main buildings, following continental practice, had been placed on stone platforms; the wood was painted; and the roofs were made of tile. In the Nara tem-ples, only minor buildings had their wood left unpainted and had been fitted with roofs of thatch or bark shingles. Now, these techniques were also used for the main halls. - eBook - ePub

Japan

A Short History

- Mikiso Hane(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Oneworld Publications(Publisher)

Other reforms included systematization of tax collection, the adoption of a military conscription system (which was abandoned in 792 because of its inefficiency), and the establishment of checkpoints at strategic places to restrict the movement of people such as peasants fleeing tax collectors. Another Chinese practice that was adopted was the establishment of a permanent capital at Nara in 710. Prior to this the political center was wherever the Emperor resided. Now for the first time an elaborate capital city patterned after the Tang capital of Zhang-an was constructed. In 784 the Emperor Kammu (737–806) moved the capital to Heian-kyō (Kyoto). The era known as Heian Period commenced in 784.The policy of adopting Tang administrative and legal practices in order to strengthen the imperial court resulted in the centralization of authority under the imperial government. Emperors, however, seldom exercised authority directly; they relied on the court officials to oversee the administrative affairs. Imperial regents also emerged as powerful leaders. Initially regents served during the minority of the Emperor or during the reign of an Empress but toward the end of the ninth century the regency came to be occupied by members of the Fujiwara family, descendants of a court official who helped to institute the Taika reforms. The Fujiwara members served as regents regardless of the Emperor’s age, and came to monopolize the post. They remained as top court officials even after the imperial court lost real power with the rise of the warrior class at the end of the Heian Period. Their descendants emerged as key figures in the modern period.Fujiwara family members extended their power by intermarrying with the imperial family, and by increasing their holdings of tax-free estates. The sumptuous lifestyle of the Fujiwara clan and the emergence of the Heian court as the nerve center of Japan resulted in a flourishing of cultural and intellectual life.While the Fujiwara clan was exercising power at the center, the outlying regions were beginning to witness the rise of military chieftains who were gradually extending their control by increasing their shōen holdings. At the court Fujiwara political monopoly was beginning to be challenged by the Emperors. The first Emperor who sought to exert direct authority was Emperor Shirakawa (1053–1129) because during his reign there were no dominant Fujiwara family members. After he retired he sought to exclude the Fujiwara family from the government by acting as the guardian of his successor who was a child. This practice was continued by subsequent retired Emperors who usually entered a monastery. This political practice came to be known as “cloister government.” - eBook - PDF

A History of Japan

From Stone Age to Superpower

- K. Henshall(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

In his ‘Elegy on the Impermanence of Human Life' he laments the passing of youth, the onset of old age, and the life of old people: 13 … with staffs at their waists, They totter along the road, Laughed at here, and hated there. This is the way of the world … The greatest victim of the age, however, may have been the central govern- ment. Its overall tax revenue was dwindling. The increasing independence 26 A History of Japan of the private estates also eroded respect for central authority. No doubt aggravated by ongoing intrigues among court factions, by the end of the period there was already a certain sense of decay in the authority of cen- tral government. 14 This was ironic, for the period was the heyday of the ritsuryo system, which was meant to spread central imperial authority throughout the land. 2.2 The Rise and Fall of the Court: The Heian Period (794–1185) Emperor Kammu (r.781–806) was particularly unhappy in Nara, and in 784 he decided it was time to move the capital again. No-one quite knows why. He may have felt oppressed by the increasing number of powerful Buddhist temples in the city. Or, since there had been so many disasters in recent times, he may simply have felt it was ill-fated. In any event, he left in a hurry. After a few years' indecision a new capital was finally built in 794 a short distance to the north, in Heian – present-day Kyoto. Like Nara, it was built on Chinese grid-pattern lines. Unlike Nara, it was to remain the offi- cial capital for more than a thousand years. At Heian the court was in many ways to reach its zenith. In its refine- ment, its artistic pursuits, and its etiquette, it rivalled courts of any time and place in the world. However, the more refined it became, the more it lost touch with reality, and that was to cost it dearly. The Heian court gave the world some of its finest early literature. - eBook - PDF

The Pursuit of Harmony

Poetry and Power in Early Heian Japan

- Gustav Heldt(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Cornell East Asia Series(Publisher)

Chapter One Heian Histories of Poetic Harmony Uta in Early Heian History Conventional histories of Japanese poetry tend to begin their accounts of the Heian Period with the years surrounding the compilation of the Kokinshū at the start of the tenth century. As an imperially sponsored anthology, this poetry collection is seen as epitomizing a newfound in- terest in the native language and culture that allegedly distinguish the Heian Period from its more sinophilic predecessor. If we look closely at the preceding century, however, we see a more complex picture, one in which distinctions between genres such as shi or uta were less germane than distinctions in the performative contexts in which poems oper- ated. Most of these practices have not been investigated in detail, and some of them have been virtually ignored in modern scholarship. This chapter will consider how these performative contexts developed as responses to political tensions and changes within the court commu- nity and the ways in which they can help provide new understandings of what made the later Kokinshū an imperial project. Although the Heian Period has typically been portrayed as the first sustained development of a native culture in the form of vernacular writing, painting, and architecture, it can perhaps best be distinguished from its immediate predecessor for its pronounced turn toward continental forms of political and social community. The reigns of the first four sovereigns of the Heian Period, Kammu (781–806, r. 781– 806), Heizei (806–809, r. 806–809), Saga (786–842, r. 809–823), and Junna (786–840, r. 823–833), witnessed a pronounced infusion of continental culture into the court’s elite, from official garb to palace architecture, court ritual, and education. With the establishment of an urban center at Heiankyō, continental forms of literacy were - eBook - PDF

- Mikael S. Adolphson, Edward Kamens, Stacie Matsumoto(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- University of Hawaii Press(Publisher)

However, as Hurst’s and Friday’s studies show, and as many of the essays in this volume suggest, figures, events, relationships, and policies in Heian society were much more complex than that, and the most in-teresting part of such stories is often that which is played out in the spaces in be-tween the sites in which such major characters perform and in the often tangled Between and Beyond Centers and Peripheries | 3 account of what transpires in or as a result of their interaction. The complexity that is suggested here represents a diffuseness, a multiplicity of forces and loci of action, and a plurality of voices and actors in shifting roles rather than an isolated society centered on one elite, one cultural modus operandi, one set of beliefs, or any seemingly simple pairings of actors or sites. What emerges in place of the former and simpler dichotomous image of a top and bottom, center and periph-ery Heian Japan is a number of newly observed patterns, configurations, and themes that deserve to be noted for what they indicate in the relations between a variety of centers and peripheries — and in other spaces in between them. If the Heian Period was indeed an era of fundamental changes, then there are also some fundamental changes in our images and understandings of it that should be given serious consideration. These are suggested by the essays collected here, and might be organized as follows. The Early Tenth-Century Turning Point Several of the essays in this volume indicate that there was something of a quiet watershed in the first half of the tenth century, in which those holding power at the political centers had no choice but to adopt a less rigid state apparatus. The result was a new system of communicating, ruling, and administrating that relied primarily on the personal and private powers and abilities of the people in-volved while still retaining the basic structures of the general social hierarchies. - eBook - PDF

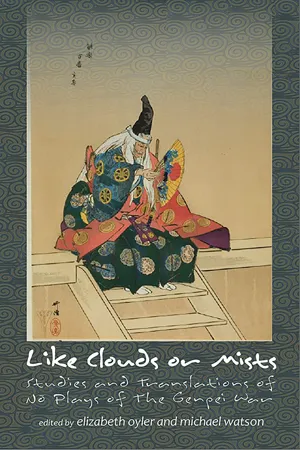

Like Clouds or Mists

Studies and Translations of No Plays of the Genpei War

- Elizabeth A. Oyler, Michael Watson, Elizabeth A. Oyler, Michael Watson(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Cornell East Asia Series(Publisher)

The experimental intermingling of lyrical and historiographical modes in linguistic contexts is mirrored on social registers as well. The warrior class, which had been isolated socially and geographically from authority and cultural production throughout the Heian Period, began to encroach on political and cultural spaces that had formerly been occupied only by the central aristocracy. While on the one hand, reverence for established forms and a profound nostalgia for the past remained central to the way the new power-holders thought and wrote about their world, on the other, they were confronted by new realities Oyler_Like Clouds_TXT_8.5X11_NXP.pdf Tuesday, Apr 08 2014 15:38 2 1 | OYLER that shaped the way they framed these impulses and expressed them in literature and drama. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Heike monogatari and the nō drama, two arts deeply involved in articulating the relationship between the new cultural terrain of the present in their reanimations of the past. No strong consciousness of the warriors as a literary or historical subject occurred before the medieval period. A few early records of warrior exploits had appeared during the late Heian Period; it is only with the several conflicts in the 1150s through the 1180s that the warriors become prominent features in literature and historical records. But from the time Minamoto Yoritomo 源頼朝 (1147–1199) won the Genpei War (1180–1185) and created a new branch of government to oversee warrior affairs, warriors and the political office of “shogun” would hold a vital official position, even when its seat was contested or unoccupied, until the 1860s. Although the Heike presents both a new narrative subject and a new mode of expression, even a cursory reading of any Heike variant reveals profound debts to traditional modes of writing, particularly to historical writing, and more specifically historical tales (rekishi monogatari 歴史物語), a hybrid form that emerged in the eleventh century.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.