History

Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gutenberg was a German inventor and printer who introduced the movable-type printing press to Europe in the 15th century. His invention revolutionized the production of books and other printed materials, making them more accessible to a wider audience and significantly impacting the spread of knowledge and ideas during the Renaissance and beyond.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Johannes Gutenberg"

- eBook - ePub

Alphabet to Internet

Media in Our Lives

- Irving Fang(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Printing would later undergird the Enlightenment that substituted reason and scientific inquiry for tradition and doctrine. It would lead to declarations of human rights and to governments based on laws and constitutions. Could any of this have been imagined in the Mainz goldsmith’s shop where Johannes Gutenberg crafted a new way to produce books? The exact date that he started using movable type is not known but it was about 1440. In 1455 he sold copies of his beautiful folio Bible.Printing today is so deeply embedded into our lives that some mental effort is needed to imagine the world without it. We might conclude that, by providing the means for spreading information to a broad segment of the population, printing set the basis for democracy in all the nations that now enjoy it. True, but printing also exists in dictatorships. Wherever printing has gone it has been followed by censorship and propaganda. As far back as 1486 censorship of the printed word can be traced to Archbishop Berthold von Henneberg in the same German city of Mainz where Gutenberg had his printing shop.3A Chinese InventionGutenberg did not invent printing. Centuries before him, people were carving images or text into blocks of wood or clay, then smearing ink on what they had done and applying it to some sort of surface. Gutenberg did not invent the printing press either. He made use of a press that was commonly used for crushing olives or smoothing clothes. Gutenberg was not even the first person to use typography. That had been done in China and Korea, Buddhist lands where the repetitive act of making impressions was in keeping with religious practice. Yet it is the German goldsmith who is credited with one of the world’s most important inventions, a superior printing system that used hard metal punches to make soft lead type of a precise height and an oil-based ink that stuck to the type. It was Gutenberg who began the process that moved the world into the Modern Age. Printing led Europe there, and Europe led the rest of the world. What Gutenberg invented was a remarkable, efficient printing system . And he did it in a time and place ready for the change it brought.McLuhan said, with a touch of humor, “The purpose of printing among the Chinese was not the creation of uniform repeatable products for a market and a price system. Print was an alternative to their prayer-wheels and was a visual means of multiplying incantatory spells, much like advertising in our age.”4 - eBook - PDF

Rewriting Nature

The Future of Genome Editing and How to Bridge the Gap Between Law and Science

- Paul Enríquez(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

1 A Momentous Time for Humankind Human ingenuity is marvelous. It boils down to an impeccable and often ethereal balance among its constituent elements, including knowledge, curiosity, creativity, and action. When the magnitude of each element expands in harmony, human ingenuity becomes transformative. It translates to power—the kind that transforms the world! This book is a testament to that power. Whether you are holding it in your hands or scrolling through pages on a touchscreen, you and I are able to communicate through this medium because, once upon a time, human ingenuity led to the creation of one of the most significant and consequential inventions of all time: the printing press. Johannes Gutenberg, a German goldsmith who lived in the early to mid-fifteenth century, is generally credited with inventing the printing press circa 1436. 1 Gutenberg did not invent books. In fact, he did not even invent printing. Long before the Renaissance, woodblock printing had already been customary during the seventh and eighth centuries in China, Korea, and Japan. 2 And the metal, movable-type system of printing, which originated in Korea, had been used since the eleventh century. 3 Gutenberg’s contribution rested on his ability to concoct a novel mechanical contrap- tion to mediate ink transfer between the movable type and paper. He used prior knowledge to adapt screw mechanisms found in antecedent inventions—namely, the wine, papermaker, and linen presses of the time—as the basis to create the mechanical, movable-type printing press. 4 But he did not stop there. When he realized that the conventional water-based ink was not durable for printing purposes, he developed oil- based ink, which, as it turned out, bonded more effectively with the types. 5 The amalgam of knowledge, curiosity, creativity, and action aimed at speeding up the printing process, which culminated in the ingenious design of the first movable- type printing press, fundamentally transformed the world. - eBook - ePub

Muslims and the New Media

Historical and Contemporary Debates

- Göran Larsson(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 1The Print Revolution

From oral communication to print media

Trust in writing will make them remember things by relying on marks made by others, from outside themselves, not on their own inner resources, and so writing will make the things they have learnt disappear from their minds. Your invention is a potion for jogging the memory, not for remembering. You will provide students with the appearance of intelligence, nor real intelligence. Because your students will be widely read, though without any contact with a teacher, they will seem to be men of wide knowledge, when they will usually be ignorant.(Plato, Phaedrus, 275a)1Even though Johannes Gutenberg (1394/99–1468) of Mainz is often described as the founding father of print technology, he invented neither printing nor movable type, these technological innovations having already been developed in China long before the fifteenth century. His contribution to the history of printing is mainly connected with the fact that he perfected printing with movable type and by doing so brought print technology closer to its modern appearance.2 According to some estimates, the number of books that had been printed by the year 1500 was close to 13 million.3 These figures are of course difficult to substantiate and we should treat them with great care. Still it is relevant to talk about a print revolution. But why were the Ottomans so slow in adopting the technological innovations developed and refined by Johannes Gutenberg?To come closer to an answer to this large question, it is necessary to delimit and define the scope of this chapter and to specify its aims. The first aim is to give a general background to the introduction of the printing press in the Ottoman Empire. In order to discuss the impact of printing, however, it is essential to consider how the shift from oral to written communication transformed societies dominated by Muslim and Islamic traditions. This is therefore the second aim of the chapter, which also contains general discussions about knowledge, memory and text in Islamic traditions. This backdrop is important because it casts light on how authority was established and conveyed prior to and after the introduction of the printing technology. This general background will also make it easier to understand the debate that followed with the introduction of the printing press in the Ottoman Empire by the beginning of the eighteenth century. The main focus, however, is on how various Muslim authorities have discussed the introduction and rise of the print media. - eBook - ePub

Events That Formed the Modern World

From the European Renaissance through the War on Terror [5 volumes]

- Frank W. Thackeray, John E. Findling, Frank W. Thackeray, John E. Findling(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

7 The Development of Movable Type, c. 1450

Introduction

No other invention contributed as much to the dissemination of knowledge during the Renaissance than the development of printing through the use of movable type. Historians credit Johann Gutenberg, of Mainz, now in Germany, with this invention and note that a Bible, called the Gutenberg Bible, was the first book published (in 1456) using movable type. There is some evidence that movable type was known in China as early as the eleventh century, Korea in the thirteenth century, and in Turkey sometime later, but it is unlikely that Gutenberg was aware of this. His invention came about when it did because of the need for a better method of written communication, spurred by the spread of literacy to laypeople, a rise in the interest in collecting fine manuscripts, and a desire for both secular and religious literature. Demand was high, and Gutenberg found a way to increase the supply.The facts of Gutenberg’s early life are shrouded in uncertainty. The year 1398 has long been accepted as his probable birth year, but Albert Kapr, in his 1996 biography, asserts that Gutenberg was born on June 24, 1400. His father, who was nearly 50 at the time of Johann’s birth, was a prominent merchant in Mainz; his mother, much younger, came from a patrician family. Both parents would have been literate and would have recognized the value of a good education. It is not known whether Gutenberg attended school in Mainz or learned to read and write at home, but it is likely that he went to a church-run day school. To have produced the Bible he did, he would have had to have learned Latin very well somewhere, and quite possibly, he learned his Latin at Erfurt University between 1418 and 1420.During the 1420s, he lived in Mainz, caring for his widowed mother and learning the goldsmith’s trade. There was a good deal of civic turmoil in Mainz at this time, mainly concerning matters of town finances, taxes, and the interests of competing factions, and perhaps because of this Gutenberg left the city in 1430 and lived in Strasbourg for a number of years. It may have been in Strasbourg that he began to develop the concept of printing with movable type; at any rate, he was back in Mainz by the mid-1440s, and in 1450, he borrowed some money from a lawyer, Johannes Fust, and set about capitalizing his invention. Two years later, Fust loaned Gutenberg more money and became his partner. It seems not to have been a happy arrangement, however, for in 1455, Fust seized most of Gutenberg’s printing equipment after the printer had fallen behind in his payments. This equipment was given to Peter Schoeffer, who worked for Fust and would soon marry his daughter. As for Gutenberg, he carried on with his printing work the best he could for a few more years, but by 1460, he had retired from the trade. The local archbishop gave him a pension in 1465, but he did not have much time to enjoy it. He died on February 3, 1468. - eBook - ePub

Learning Technology

A Complete Guide for Learning Professionals

- Donald Clark(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Kogan Page(Publisher)

The printing press was not invented by Gutenberg, nor was it a single technology. Although the Chinese invented paper, block printing and even moveable type, their character-based language made Gutenberg-type presses impractical. It was the existence of another piece of technology, the Roman alphabet, that made the printing press practical. This is yet another example of how software can be the real driver behind a technological advance.Early printing technology

Brian Arthur (2009) shows that technology is often an accumulation and convergence of previous technologies. Printing with moveable type was being experimented with from the 1430s onwards, with Gutenberg developing moveable type, alloys for type and reusable type, modelled on existing screw presses. Together with the development of indelible ink and cheap paper, this combination of technologies enabled Gutenberg to create his famous Bible.The core technology in the 15th century was moveable type. The compositor set each letter, in reverse, on sticks, bedded it down and adjusted as necessary, with each page being separately printed. This was not easy, and just like manuscript writing, errors were easy to make. The initial investment needed was quite high and if sales were better than expected the whole process had to be repeated in order to produce more copies. Paper remained a problem even after the printing press was developed, as it was so expensive. Gutenberg got into deep debt and had to pass his workshop over to his investor. One of his first books, the Gutenberg Bible, took two years to typeset and print.What the printing press did was scale production and distribution. The number of books available increased significantly, prices plummeted and the idea of writing new works to be printed, as opposed to just reading fixed texts, took hold. It was a technology (or set of technologies) that was to cause irreversible change in the world. - eBook - PDF

Icons of Invention

The Makers of the Modern World from Gutenberg to Gates [2 volumes]

- John W. Klooster(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

The famous early English printer, William Caxton, learned the trade of printing based on Gutenberg technology in Europe and established his press in Westminster, England, in 1476. Consistent with the Gutenberg idea of printing type, which was calligraphic and resembled handwriting, Caxton developed the Black Letter type that resembled the writing of the monks of Haarlem, Holland. Though considered by some to have been the finest printer of his day, Caxton is classified as an amateur printer because he was mainly a man of letters and politics. The Reformation in the sixteenth century, the Industrial Revolution in England during the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries, and the advance of science associated with the Scientific Revolution were all pro- moted by printing. WHAT EXACTLY DID GUTENBERG INVENT? Gutenberg worked in secrecy, but careful research by experts has identified his main inventions, developments, and work, which can be classified into two fields: • Methodology and equipment for printing that included three components: type, ink, and press • Printing (known as relief or letterpress printing) using a plate-like member in a retaining frame, the member having raised surface portions that com- prised individual letters and characters that were inked and then trans- ferred, by contact under pressure, to paper In these fields, Gutenberg achieved various inventions and developments that were usually accomplished by, and associated with, substantial trial and error experimentation. A concept of printing may well have occurred to Gutenberg in an instant of time, but to reduce his concept to practical, com- mercially useful embodiments required remarkable dedication and singleness of purpose, exerted over much time, with experimentation, and effort that evidently extended over at least about 20 years and involved significant cost. Gutenberg’s main invention was a process for printing. - eBook - PDF

A Typographic Workbook

A Primer to History, Techniques, and Artistry

- Kate Clair, Cynthia Busic-Snyder(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

46 A T Y P O G R A P H I C W O R K B O O K Certainly Gutenberg’s commitment to refine-ment of the printing process and to solving a series of problems and challenges is legend-ary. Some historians argue that Laurens Coster of Holland developed the art of print-ing slightly before or around the same time as Gutenberg; others argue that Coster merely stole some of Gutenberg’s trial forays into printing. Still others propose that we know too little of the actual details of Gutenberg’s life to credit him with the invention of print-ing. This controversy remains an unre-solved, contentious issue among historians. Gutenberg: The Metal Craftsman The generally accepted version of the printing story is that Gutenberg, an accom-plished metalworker and caster, was working toward developing a technique of printing text for books as early as 1438. He joined with goldsmith Johann Fust , who agreed to underwrite the cost of Gutenberg’s printing experiments, provided Gutenberg repay him. Gutenberg adapted a press that was origi-nally used to press grapes for winemaking. He developed a method of casting metal type in single pieces that varied in width but maintained a precise and consistent height. He developed a chase (a rectangular iron frame in which pages or columns of type are composed) to hold the type in posi-tion on the printing press bed. Finally, he formulated inks to the correct consistency for use with lead cast type, and perfected techniques for registration (accurate align-ment of type and images), for clean and precise impressions, and for keeping the edges of the printed page ink-free. In short, Gutenberg worked out the details that made printing a viable reproduction process. 3.3 This press is similar to the one modified and perfected by Gutenberg. Movable, Reusable Type Gutenberg’s brilliant innovation was the production of individual, reusable characters, rather than casting an entire page as one solid piece. - Malcolm Vale(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

5 The impact of printIn those days, in the city of Mainz, located in Germany on the banks of the Rhine – and thus not in Italy as some have falsely written – was invented and devised by the Mainz citizen Johannes Gutenberg that marvellous and hitherto unheard-of art of printing and impression of books. (Johannes Trithemius, Annals of Hirsau abbey , for the year 1450)1Who dares to glorify the pen-made book? / When so much better brass-stamped letters look? (Wendelin of Speyer, printer, signing off his work in the colophon to his edition of Sallust (1470))Renaissance, Reformation and print2The period which saw the advent and subsequent course of the Northern Renaissance witnessed a number of seminal discoveries and innovations. These, it is argued, were to carry a lasting significance for the history of both Europe and the wider world. Among them, the invention of the mariner’s compass, the introduction and development of gunpowder, the discovery of Africa and the New World,3and the advent of printing with movable type have been singled out as especially seminal and far-reaching in their consequences. Together with the ‘Eyckian revolution’ in painting, the rise of polyphonic music, and the genesis of humanistic techniques of textual criticism, printing can be described as a true ars nova (‘new art’).4In origin, it was an exclusively Northern European innovation. Renaissance Italy very soon inherited, adapted and exploited what was essentially a German discovery. The ‘Germans’ (who at that time were thought to include the Netherlanders) could therefore not all be equated by contemporaries and later commentators with the ‘barbarians’ dear to Italian myth. A growing fifteenth-century cultural clash between Germans and Italians came to a head with the advent, in the mid-century, of printing and the printing press. Not only had the Italian humanists constantly asserted their superiority over their Northern contemporaries in the revival and refinement of the Latin language but, they claimed, the Germans (and the Northerners in general) had left copies of precious classical texts to rot, neglected and unread, in monastic and diocesan libraries. But, as the German abbot Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516) wrote,5the Italians could not take the credit for all the best discoveries of the age. The inception and origins of Johann Gutenberg’s (c. 1400–68) invention are obscure. He was a goldsmith, son of a goldsmith employed in the episcopal mint at Mainz, and appears to have conceived the idea of printing with movable type by the 1440s. It was apparently first put to use in c.- eBook - PDF

- George Parker Winship(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

I JOHN GUTENBERG AND THE INVENTION OF PRINTING 1400-1460 THE RFFLNELAND BOOK MARKET IN 14ΟΟ THE Gutenberg Bible is a landmark in the history of civil-ization, a turning point which diverted the course of cul-tural development into new and deeper channels through which the main currents of human thought flowed for the ensuing five hundred years. This impressive piece of handiwork, more clearly than most outputs of human effort, came into existence as the inevitable, inescapable result of forces that permeated the communal Ufe of the time and the place. These forces had been gaining impetus for two centuries with a flow as steady and resistless as that of a glacier of the Ice Age, spreading out over Europe until they embraced the entire civilized community and dominated every phase of its daily Ufe. Equally is it true that the invention of printing, which culminated with the appearance of this First Printed Bible, resulted directly from commonplace circumstances which altered the humdrum course of the life of an otherwise in-conspicuous young man. [ ι ] PRINTING IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY One qualifying statement needs to be emphasized—the First Bible is the first piece of printing of sufficient size and importance to require a binding before it could be used. It was not, by at least fifteen years, the first printing done with movable types, nor the first produced for sale under commercial conditions. It is not the oldest existing specimen of such printing, nor the first printing whose date can be established, by at least five years. These distinctions have at times been claimed for the Bible, by thoughtless popular-izes, who not infrequently have also claimed, and quite justifiably, that this monumental piece of printing exhibits a mastery of typographical technique which left nothing of essential, basic importance that had to be changed subse-quently. - eBook - ePub

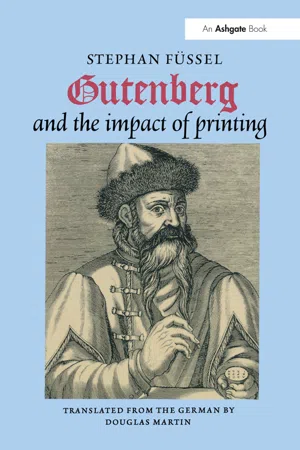

- Stephan Füssel(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

We simply do not know what Gutenberg did between 1444 and 1448; but there is evidence to show that he was back in Mainz by 17 October 1448. On that day he took out a loan of 150 gulden at 5 per cent interest from his cousin Arnold Gelthus. Just as in Strasbourg, Gutenberg sought business relationships with bankers and merchants with whose financial support he could put his new technical developments into practice. By 1450 his experiments had reached the stage that he could go ahead with the setting and printing of broadsides and extensive books.BRINGING THE TECHNICAL INVENTIONS TOGETHER

Gutenberg’s invention is as simple as it is ingenious: texts were broken down into their smallest components, i.e. into the 26 letters of the Roman alphabet, and from placing single letters in the right order the new text required would result time and again. Texts had been copied over the centuries by writing them out completely and sequentially, or by cutting them equally completely in wood (text and illustrations were being cut in wood for such contemporary “blockbooks” as prayers, ars moriendi or cribs for sermons), but now only the letters of the alphabet had to be cut and supplies cast and they would always be available for setting up whatever text was chosen. His second brain-wave was in effect as simple as it was technologically revolutionary: instead of transferring the ink to the paper by rubbing as had been done for 700 years in Asia, Gutenberg used the physical action of the paper- or wine-press to transfer the ink from typematter to dampened paper with one even and forceful impression (see Plate 2 , the first contemporary woodcut to show a press, dating from 1499).Very many stages were naturally called for in the development of this apparently obvious and straightforward procedure. Punches for individual letters, skilfully cut by goldsmiths, had been around for some time, and the engraving of sacred artefacts such as chalices and monstrances was a widespread technique. Casting methods were in use whether for bellfounding or coinmaking. It was a question of realising the idea by bringing together individual letters, and casting techniques, and finding the appropriater constituents of the typemetal. At the heart of Gutenberg’s discovery stands the development of a casting instrument which allowed the casting void to be precisely adjusted so that identical supplies of each type could be cast. No original instruments have survived from the fifteenth century, and the so-called adjustable hand mould shown in the textbooks only reached that precise form some two centuries later, but the earliest types which do survive and the quality of Gutenberg’s impression make it evident that some comparable casting instrument must have been part of the original invention. - Paul M. Dover(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Garzoni’s rhetoric is flamboyant, but his twin emphases – the abundance and affordability of books, making them available to a much larger reading population, and the resuscitation and rescue of authors who otherwise would have remained in the shadows – are echoed by other early modern commentators. The humanist and historian Polydore Vergil (c. 1470–1555) stressed precisely these points in his On Discovery: “Books in all disciplines have poured out to us so profusely from this invention that no work can possibly remain wanting to anyone, however needy. Note too that this 1 Tomaso Garzoni, La piazza universale di tutte le professioni del mondo, e nobili et ignobili (Venice: Giovan Battista Somascho, 1586), 847. 149 invention has freed most authors, Greek as well as Latin, from any threat of extinction.” 2 Similarly, the prominent French humanist Henri Estienne (c. 1531–1598) in his work on the Frankfurt Book Fair, also stressed how the printing press had made “an abundance of books” available “to all the lands of the globe” and rescued the Muses from exile, giving them the strongest protection (firmissimum praesidium) against loss. 3 There is little doubt that, in the public imagination at least, early modern Europe is regularly associated with the invention of Gutenberg. When I describe this book project to others, they invariably mention the printing press. “The age of print,” the advent of “print culture,” and the “coming of the book” are phrases routinely invoked in descriptions of the early modern period. Such designations both overstate the pervasive- ness of the printing press’s influence, and overlook the impact of factors unrelated to the press. We must move away from the medieval–early modern bifurcation between manuscript and print, to recognize that the print revolution was only part of, and in many ways symptomatic of, broader transformations in information generation and exchange.- eBook - PDF

Advanced Typography

From Knowledge to Mastery

- Richard Hunt(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Visual Arts(Publisher)

Example of the humanist manuscript style of the 1400s that was the basis of Roman type. & molte genti CHANGING TECHNOLOGIES AND PRACTICE 17 of labour. The first printing presses were an early iteration of the assembly line that became the basis of efficient manufacture of automobiles and other mass-produced products. In a sense, the printing press was the industrial robot of its day, replacing human labour with technology. The development of the printing press in Europe anticipated production processes in other fields. The production of printed matter with a press became a model for the division of labour of mass production in the Industrial Revolution, something that has culminated in today’s industrial methods. While the work of the scribe became unnecessary, more and more printers and other craftspeople associated with printing were needed. By 1500, less than fifty years after Gutenberg’s Bible, there were printing presses in over 250 cities across Europe, with more than 20 million books estimated as having been printed. The in- creased availability of reading material encouraged more people to learn to read, which in turn led to an even greater demand for print. Some of the information contained in these books led to develop- ments in science and technology. Previously, most learning had to be started from scratch by each person in each field, because pre- vious knowledge developed by others elsewhere was inaccessible.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.