History

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German theologian and key figure in the Protestant Reformation. He is best known for challenging the Catholic Church's practices, particularly the sale of indulgences, and for his Ninety-Five Theses. Luther's actions led to the formation of Lutheranism and had a profound impact on the religious and political landscape of Europe.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Martin Luther"

- eBook - PDF

Luther's Gospel

Reimagining the World

- Graham Tomlin(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- T&T Clark(Publisher)

PART A Luther and His Gospel 2 1 Luther and His Gospel During the last millennium, the world changed radically. Marco Polo and Christopher Columbus opened up new continents, William Shakespeare and Michelangelo produced some of the most sublime pieces of art, and Napoleon Bonaparte and Adolf Hitler changed the political face of their centuries. Yet a good argument can be made that one medieval monk outstripped them all in his-torical significance. Martin Luther and the Reformation he triggered have made a huge impact not just in Europe, but also in North America, Australia and the rest of the world. Around 800 million people worldwide belong to the various ‘Protestant’ denominations, none of which would exist without the events surrounding Luther’s pro-test against aspects of Catholic Christianity five hundred years ago. Protestantism has shaped a whole new way of life for people across the Western world and beyond, which has coloured their approaches to God, work, politics, leisure, family and, in fact, to almost every aspect of human life. It played a seminal role in the early development and continuing self-image of the United States, in the emergence of democracy and economic and religious free-doms in Europe, and was one of the key movements ushering in the changes from the medieval to the modern world. Luther can-not claim credit or blame for the whole of what eventually became Protestantism, but as one who played a critical role in the emer-gence of a new church and a new way of life for millions of people, the influence of his actions and beliefs on the past five hundred years has been incalculable. The modern world can barely be under-stood without them. LUTHER’S GOSPEL 4 4 Martin Luther was not the author, but became the accidental instigator of the Protestant Reformation through his famous pro-test about the abuse of Indulgences in 1517. - eBook - ePub

- Bernard M. G. Reardon(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 3 Martin Luther: I. The Religious Revolutionary The age and the manIt has been said that ‘they who do not rightly estimate the Reformation cannot rightly understand Luther, since Luther apart from the Reformation would cease to be Luther’.1 This certainly is true, but no less true is it that apart from Luther the Reformation itself cannot be understood. He is its key figure, protagonist and spokesman alike, upon whom all others zealous for change were more or less dependent. Indeed, whether but for Luther the Reform movement of the sixteenth century would have swept over Europe in the way it did is highly questionable. What he achieved was rendered possible because the time and the milieu were matched in him by the man also, so that all the necessary elements were present to issue in events such as, in the most authentic sense, were epoch-making. That achievement was not therefore something external to him, but the utterance of the man himself and of his profound personal experience. Over the preceding century voices had repeatedly called for the reform of abuses and corruptions, but there had emerged no guiding principle on which Reformation could successfully be carried through, nor a dominant personality to give it impetus.As opinions varied so counsels differed, whereas what was needed – the outcome proved it – was the dynamism of a spiritual conviction that struck at the very heart of the evils which men of conscience yearned to see cast out. Luther it was who reached such a conviction and proclaimed it forthrightly and fearlessly. Yet to begin with it was one the full implications of which he himself did not comprehend. Only as opposition mounted did he sense the extent either of the changes that would perforce be necessary or the risks and temptations to which he, a monk and an academic, was to be exposed when thrust upon the stage of world politics. But as he was wont afterwards to declare: ‘I simply taught, preached, wrote . . . otherwise I did nothing. . . . The Word did it all.’ That, politically speaking, he could have set Europe alight, he realized, but he knew too that this was no game for him to play. For the remarkable thing is that he did not feel himself to be an autonomous agent, deploying his own resources against however powerful odds -in short, a hero challenging fate – but the instrument rather of an overriding providence and purpose. Quite apart from his talents as a man, which in any case were outstanding, Luther’s sense of mission, of doing the work to which he firmly believed, despite every doubt and difficulty that might confront him, God had called him, made him in truth a prophet; for even the soberest historian can scarcely withhold the word. Moreover, his ability to communicate verbally his overwhelming intimations of the reality of God has rarely been equalled in Christian history. In this not even St Augustine surpassed him.2 - eBook - ePub

The Other Renaissance

From Copernicus to Shakespeare: How the Renaissance in Northern Europe Transformed the World

- Paul Strathern(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Pegasus Books(Publisher)

Martin Luther AND THE PROTESTANT REFORMATIONW ITH THE ADVENT OF Martin Luther, this previously imagined madness took a turn towards reality. Tradition has it that on 31 October 1517, the thirty-three-year-old Martin Luther publicly nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the wooden door of the Castle Church of Wittenberg. Whether or not this act actually took place in quite this fashion, the symbolic force of the tale cannot be denied. This event marked the beginning of Protestantism, and an end to the hegemony of the Holy Roman Church in western Europe. The Reformation of the Church had begun.Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses was a comprehensive demand for a reform of the Church. The most significant and divisive idea deriving from the theses was his insistence that believers had direct access to God through prayer, and so had no need of intercession on their behalf through a priest. There was thus, by implication, no need for the Holy Roman Church, the pope, the priesthood, holy relics, or indeed the entire apparatus of the established Catholic religion. Luther’s act would divide Europe, plunging the entire western continent into decades of religious persecution and widespread social unrest, finally culminating in the most destructive war Europe had yet witnessed. Nothing would be the same again.This would, in effect, be the spiritual and secular conflagration which became the background to the northern Renaissance. Just as Ancient Greece had flourished through the upheavals and conflicts between its city-states – even the conquest of Athens by Sparta in the Peloponnesian War – so would the Other Renaissance take on its own distinctive cultural transformation against the background of war. In this way, the loosening of the ties binding the medieval world would enable a freedom in which the Renaissance could evolve.Martin Luther was born on 10 November 1483, the first of several brothers and sisters. His birthplace was Eisleben, a small town in a copper-mining region of eastern Germany, ruled over by the counts of Mansfeld in the name of the Holy Roman Emperor. Apart from a single visit to Rome on a pilgrimage, Luther would spend his entire life living in and around this region of Upper Saxony. - eBook - ePub

Leadership Across Boundaries

A Passage to Aporia

- Nathan Harter(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

One could argue that especially in his polemical works, Luther’s apparent inconsistencies and rhetorical excesses might have served as a turbulent surface for a calm under-layer, such that they were lapses in judgment or extravagances attributable to the heat of the moment. Otherwise, perhaps there was a persisting core to his beliefs. The problem for us today is that scholars continue to quarrel over what that under-layer might have consisted of, except to the extent that it was grounded in his religious faith. Thoughtful critics are tempted to give up and say that Luther was simply not altogether coherent. He was a man of contradictions (see e.g. Pettegree, 2015, p. 283). The possibility of this finally did not seem to trouble Luther, who frequently held seemingly contradictory positions with glee, yet the turbulence and contradiction in his soul arguably mirrors the turbulence and contradiction in the world he inhabited. We are not able to shed much light today on this psychological question.Nevertheless, I am aware of nobody who would contend that Luther had no impact on his historical context. On the contrary, he has been ranked as one of the most significant figures in European history12 and certainly a founding influence on the German nation. His leadership is unquestionable, even if his thinking about leadership was never clear. As one biographer put it, “Between 1517 and 1530, Luther stood toe-to-toe with emperors and kings and contended with many of the forces that have shaped modern life” (Nestingen, 1982, p. 11). The world is different today because of him.1312 . Time magazine ranked Luther the seventeenth most influential person in human history (Skiena & Ward, 2013).13 . Febvre acknowledges that Luther was consequential, but only because of his immense failure (1929, p. 303f).In 1844, the social philosopher Karl Marx said of the Reformation in Germany that it “originated in the brain of a monk” (1978, p. 60), yet in 1852 he explained: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly found, given and transmitted from the past” (1978, p. 595). In fact, he went on, “The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living” (1978, p. 595). Then Marx presents as exhibit A for this proposition the historical figure of Martin Luther, the monk in whose brain the Reformation supposedly began. As we pointed out earlier (and Marx here mentions openly), Luther was not issuing something new, so much as something quite old. Yet he did lead. He was not just a victim of his circumstances. Neither was he a puppet of his spiritual ancestors. How is that possible? - eBook - PDF

Luther and Calvinism

Image and Reception of Martin Luther in the History and Theology of Calvinism

- Herman J. Selderhuis, J. Marius J. Lange van Ravenswaay, Herman J. Selderhuis, Günter Frank, Bruce Gordon, Barbara Mahlmann-Bauer, Tarald Rasmussen, Violet Soen, Zsombor Tóth, Günther Wassilowsky, Siegrid Westphal, David M. Whitford(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht(Publisher)

In the process, Reformed Christians in the early modern period who wished to provide a his- torical account of the Reformation and its role in bringing the true church back to full strength could hardly avoid dealing with Martin Luther and his contribution to the movement. While including Luther in the narrative was accepted practice, assessing his significance was rather more challenging, mostly because of the difficulties in presenting Luther and his actions in the early Reformation without providing fodder for Catholic accusations that he was primarily responsible for fracturing the unity of Christendom. The charge of sectarianism and divisiveness against Luther was heightened by the theological controversies that had divided © 2017, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525552629 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647552620 the Reformed and the Lutherans from the late 1520s onwards (cf. e. g. Burnett: 2005, 45–70), another topic that most Reformed historians sought to address. Finally, Reformed historians had to find a way to highlight Luther’s crucial work without turning him into a saint or over-emphasizing his role, especially when addressing a Reformed audience. The research conducted for this contribution has shown that there is no one single Reformed perspective on Luther in historical writings up to 1750. Instead, the image of Luther in these works varies depending on the genre and the au- dience of the work in question. In other words, when Reformed writers penned a history of the Reformation rebutting a Catholic perspective, the Reformed tended to give a positive view of the German Reformer. When writing for a Reformed audience, the historians tended to be more willing to highlight Luther’s weak- nesses or flaws. If the work was intended as a historical account, the assessment of Luther was more even-handed than in works that sought to give a providential reading of history, as in martyrologies, for instance. - eBook - PDF

Martin Luther's Legacy

Reforming Reformation Theology for the 21st Century

- Mark Ellingsen(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

1 We are well acquainted with Martin Luther, we think. 1 Some read- ers will already be familiar with the story of how this young man, born to an upwardly mobile peasant couple (at least his father) in 1483 and planning on a career in law, vowed to become a monk, joining the Augustinian Order, after safely escaping a frightening thunderstorm. Others will also be aware of how as a brilliant student and protégé of the Order’s leader Johann von Staupitz, trained in Nominalist thought and Augustine’s theology, the subject of our book was called to the faculty of Saxony’s Wittenberg University. And most everyone knows that dur- ing his first years on the faculty of this new university, after (some think it happened prior to) a Tower Experience which changed his understand- ing of St. Paul’s concept righteousness of God, this young professor went on heroically to challenge the selling of Indulgences, leading to the Reformation. Luther’s own account of his breakthrough in the Tower suggests it happened in 1519, as the other events he describes in the nar- rative as happening at the time of his life-changing experience (including his having lectured on Galatians and Hebrews as well as initiating a new round of lectures on the Psalms) transpired in that year. However, the essence of what he learned from The Tower Experience already appears in a 1516 sermon, as he claimed that God’s work is creating righteous- ness. 2 Many historians and social critics even think of Luther as the first modern man, asserting individual judgment and conscience over the norms of the medieval establishment. 3 Others insist that he was a CHAPTER 1 Introduction: Luther the Reformer, Past and Present © The Author(s) 2017 M. Ellingsen, Martin Luther’s Legacy, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-58758-9_1 2 M. ELLINGSEN thoroughly late medieval German. 4 For some, he is a great theologian, the father of Protestantism. For others he is a heretic. And still others see him as a Catholic theologian. - eBook - PDF

Western Civilization

A Brief History, Volume II: Since 1500

- Jackson Spielvogel(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

The agitation for certainty of salvation and spiritual peace was done within the framework of the “holy mother Church.” But disillu-sionment grew as the devout experienced the clergy’s inability to live up to their expectations. The deepening of religious life, especially in the second half of the fif-teenth century, found little echo among the worldly-wise clergy, and this environment helps explain the tre-mendous and immediate impact of Luther’s ideas. Martin Luther and the Reformation in Germany Q F OCUS Q UESTION : What were Martin Luther’s main disagreements with the Roman Catholic Church, and what political, economic, and social conditions help explain why the movement he began spread so quickly across Europe? The Protestant Reformation began with a typical medi-eval question: What must I do to be saved? Martin Luther, a deeply religious man, found an answer that did not fit within the traditional teachings of the late medieval church. Ultimately, he split with that church, destroying the religious unity of western Christendom. The Early Luther Martin Luther was born in Germany on November 10, 1483. His father wanted him to become a lawyer, so Luther enrolled at the University of Erfurt. In 1505, af-ter becoming a master in the liberal arts, the young man began to study law. But Luther was not content, due in large part to his long-standing religious inclina-tions. That summer, while returning to Erfurt after a brief visit home, he was caught in a ferocious thunder-storm and vowed that if he survived unscathed, he would become a monk. He then entered the monastic order of the Augustinian Hermits in Erfurt, much to his father’s disgust. In the monastery, Luther focused on his major concern, the assurance of salvation. The traditional beliefs and practices of the church seemed unable to relieve his obsession with this question. - eBook - PDF

Christianity and History

Essays

- Elmore Harris Harbison(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

* In 1957, a friend of mine on the faculty of Princeton Theological Seminary, Hugh Thomson Kerr, Jr., had the task of lining up visiting lecturers for a course primarily for church-school teachers on the history of the Church. He asked if I thought I could sum up my thought about the Reformation in about 5,000 words. I have for- gotten why it sounded so easy at the time that I said yes, but this was the result: the Reformation in one easy lesson. THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION The idea of the Reformation and what it meant in the history of Christendom has a four-century history of its own. The earliest Protestants saw the movement of which they were a part as a direct intervention of God in history to chastise the Roman Anti-Christ and confound Satan. Their Romanist opponents naturally saw it as a diabolical rebellion against divine authority motivated by pride, greed, and heretical bigotry. Liberals and romantics of a later age saw in the Reformation mainly a vast upsurge of freedom, of protest against obscurantism and release from clerical bondage. To followers of Karl Marx it became a mere readjustment, on the level of religion, to deep under- lying economic changes. At one time or another, the Refor- mation has been all things to all men. Historians are agreed by now, however, on the general nature of the historical forces which Luther unwittingly released. It was these forces which gave the Reformation the momentum without which even so great a leader as Lu- ther could never have overcome the inertia which had con- fronted religious radicals for years. First of all, the Refor- mation was intimately related to the economic revival of the later Middle Ages. - eBook - ePub

- Krey(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cascade Books(Publisher)

th Anniversary Celebration of the Reformation will observe him more as the common doctor of the church than hero and prophet.We know that Luther’s critique of scholastic theology and his theological concerns with indulgences began earlier than the evening and the day of All Saint’s (October 31 –November 1 ) 1517 , but this weekend has been etched into the historical imagination over the centuries that this essay will address. Scholars have proposed that Martin Luther’s reform can now be understood as the most significant in a series of medieval and late-medieval attempts at reform.6 In some sense the Roman Catholic Church had become immune to the many attempts at reform from, for example, the Mendicant movements of the thirteenth century that were received by Pope Innocent III to the failed reforms of the Conciliar movement of the fifteenth century that foundered on the reefs of nationalism and a timeless attraction for a strong leader over against a constitutional and balanced papal monarchy. In any event, in the sixteenth century the context left Luther, the Augustinian monk and young professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg, with a proposal for reform and a number of secret sympathizers but a hardened church structure that made dialog impossible.7 He was eventually declared a heretic.8What happened on that critical day?9 The Augustinian monk and young professor at the University of Wittenberg (age 34 ), Dr. Martin Luther sent a letter to the Archbishop of Magdeburg–Mainz alerting him of the danger to the proclamation of the Gospel in his territory since the Dominican Friar Johann Tezel was marketing and exaggerating the sale of indulgences. To this letter Luther attached theses arguing theologically against the sale of indulgences.10 He did not expect the Prince-Bishop to respond to the theses, as the disputation was the right and duty of the university.11 Thus Luther was working on this issue for some time. The Wittenberg faculty including Andreas Karlstadt was preparing for theological debate.12 Luther had been researching the ecclesiastical, theological, and legal grounds for indulgences earlier in 1517 and was distressed by the great collection of relics that Prince Frederick had stored at the Castle Church—the list of which would be read publicly on All Saints Day, November 1 . Historians agree that whether or not the Theses were posted, the events of the days lose none of their historical importance.13 To some extent Luther was surprised by the broad reception that the Theses received. That the subsequent sermon “On Indulgences and Grace” (Feb. 2 , 1518 ) in German enjoyed at least twenty editions surprised Luther.14 What was and remains decisive is the Reformation’s proposal to the church catholic, a proclamation of the gospel that continues to challenge and influence Lutheran, Reformed, and Roman Catholic Christians to this day.15 - eBook - PDF

- Hubert Cunliffe-Jones(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- T&T Clark(Publisher)

Martin Luther Benjamin Drewery This page intentionally left blank Martin Luther Introduction BENJAMIN DREWERY The history of Christian doctrine has been marked by a select succession of master-minds - S. Paul, Origen, Augustine, Aquinas -who have not only stamped their personal seal on the crises and advances of their day, but continue to fertilize and fructify the course of all subsequent theology. To this exalted company, beyond cavil, belongs Martin Luther. Protestantism in all its fissiparous manifestations has for nearly five centuries drawn on him as its earthly fountain-head, and the twentieth century has witnessed the overflowing of the Lutheran streams into the pasturage of Catholicism and even of Orthodoxy. Yet the exposition and evaluation of Luther's theology remains a matter of almost unparalleled complexity. First, there is the sheer bulk of his writings; the great Weimar Edition, begun in 1883, approaches its completion in nearly sixty vast volumes. Then there is the unfamiliarity of his language and thought-forms, especially to the English-speaking. This is intensified by his complex historical setting; he was not so much zwischen den Zeiten as one who spans like no other the dying and the rising of two worlds. Nor does his temperament and character simplify the quest; tempestuous, prophetic, profoundly learned yet totally committed to the human drama, appealing and exasperating, argumenta-tive, contradictory, ironical, with something of the mystic and much of the party manager, a man of the people and supremely a man of God - the last thing Luther intended was to make life easy for later systematic theologians. The very process of his development - the late medieval monk, the arch-rebel of the religious revolution, the matured father-figure of the Reformation -makes systematic analysis of his thought a hazardous and at times an almost despairing venture. - R. W. Scribner(Author)

- 1988(Publication Date)

- Hambledon Continuum(Publisher)

14 LUTHER MYTH: A POPULAR HISTORIOGRAPHY OF THE REFORMER* The life and career of Martin Luther must be one of the best known stories of the modern period. Less well known is what we might call the 'popular historiography' of the Reformer — how he was regarded by his contemporaries and by later generations, before our modern bio-graphies came to be written. In order to explain the nature of this 'popular historiography' I want to discuss here certain 'myths' about Luther that can be found in sixteenth-century sources, and in folktales recorded during the nineteenth century. 'Myth' is used here both in a narrow sense to mean an individual narrative, and in a broader sense to designate the genre constituted by a number of similar tales. Let us establish the meaning of the term by concentrating on sixteenth-century examples, beginning with one of the most striking individual narra-tives. This was first published as a broadsheet in 1617, an d is known as the Dream of Frederick the Wise (see frontispiece). It relates a threefold dream experienced by the Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony on the evening of 3 o October, 1517 — the eve of the day on which Luther is said to have posted his Ninety-five Theses in Wittenberg. Frederick fell asleep in his castle at Schweinitz, pondering how he could assist the holy souls in Purgatory to attain blessedness, and he dreamed that God had sent him a monk of fine and noble features, a natural son of the Apostle Paul. As companions God had given the monk all the dear saints, who assured Frederick that if he would permit the monk to write on his castle church at Wittenberg he would not regret it. Since this request was affirmed by such powerful witnesses, Frederick agreed. The monk now wrote in such great letters that they could be read all the way from Wittenberg to Schweinitz, and the quill with which he wrote stretched all the way to Rome, where it pierced the ear of a lion, and began to topple the papal throne.- eBook - ePub

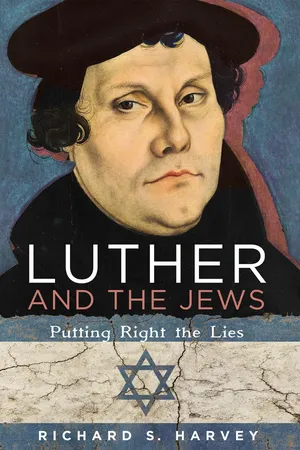

Luther and the Jews

Putting Right the Lies

- Harvey(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cascade Books(Publisher)

200,000 . Luther himself did not like the term “Lutheran,” preferring to call himself and others who affirmed the gospel “evangelical.” Today this term has different meanings in different contexts, but for Luther it meant those who stood by the good news of Jesus Christ, and recognized the need for Reformation in the church.Luther did not intend to form a new church or denomination, but rather to remain within the “one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church” (the four marks of the church, according to the Nicene Creed). His followers, and those of the other Reformers—John Calvin and Huldrych Zwingli in Switzerland, Thomas Cranmer in England, John Knox in Scotland, and many others—wanted to restore a biblical foundation to the church based on the three solas: sola Scriptura , sola gratia , sola fide (“by Scripture alone, by grace alone, by faith alone”).Following the death of Luther in 1546 , there were three main developments over the centuries, which we need to know about in order to understand his legacy today. These were Protestant Orthodoxy/Scholasticism (sixteenth to seventeenth centuries), Enlightenment Rationalism (eighteenth to nineteenth centuries) and Pietism (eighteenth to nineteenth centuries).Like the Scholastics (“school men”) of the Middle Ages in the Roman Catholic Church, such as Thomas Aquinas, who focused his energies on discussion of the philosophical nature of Christianity, the Protestant Scholastics focused on correctly interpreting Luther’s theology. The focus shifted from the experience of salvation by grace through faith to deciding what correct doctrine was, and this meant understanding the relationship between law and grace, and the place of good works. Melanchthon, Luther’s colleague and disciple, mediated between conflicting views, and decided that although good works were not necessary to earn salvation, they were still necessary in the life of a believer.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.