History

Loyalists

Loyalists were American colonists who remained loyal to the British Crown during the American Revolutionary War. They opposed the movement for independence and often faced persecution and confiscation of property as a result. After the war, many Loyalists fled to Canada or other British colonies, while others integrated back into American society.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Loyalists"

- eBook - ePub

A People's History of the American Revolution

How Common People Shaped the Fight for Independence

- Ray Raphael(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- The New Press(Publisher)

It only suggests what we already know: Loyalists were plentiful enough to turn the Revolution into a civil war, but not so numerous as to emerge the victors. The literal definition of a loyalist—“a person who professed a continuing allegiance to the King of Great Britain”—is simultaneously too broad and too narrow. It includes people who passively accepted the legitimate authority of the British government, even though they might not have been willing to act in its defense, while it excludes a good number who contributed to the loyalist cause for self-serving reasons without cherishing any special feelings for monarchy in general or for George III in particular. Contemporary patriots seldom used the term “loyalist,” with its positive connotations; they preferred to call their adversaries “Tories”—a word with a very British ring—often preceded by the adjective “damned.” (Friends of the king, in a similar manner, liked to use the term “rebel,” commonly preceded by the same adjective.) In the patriot vernacular, Tories were said to be “disaffected” to the American cause. Not signing the Association, toasting the king, quartering a British soldier—these were all marks of disaffection. The disaffected included anybody who failed to support the Revolution, even those who tried to stay neutral. Several of the most vocal of the disaffected fit the classic image of the Tory: wealthy conservatives who were obligated to the British government and who felt threatened by republican theory and the rise of the common man. 3 In rural Massachusetts, where the Revolution began, Loyalists came primarily from the ranks of the local elites, people like the Chandlers and Paines of Worcester County and the Williamses and Worthingtons of Hampshire County who had held power under the old order - eBook - PDF

The Pioneer Farmer and Backwoodsman

Volume One

- Edwin Guillet(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- University of Toronto Press(Publisher)

E.' The listing formed at that time was henceforth called 'the old U. E. list', and its names are obviously of those who were *Here is the logical attitude of an American historian relative to those who opposed the Revolution which founded their nation : Thousands of American settlers denounced the Revolution as treason and subversion, fought it, re-treated to Canada or took ship to England, leaving behind the men of faith, who went on to build a continent.' ('In Time of Trial', by Barbara Ward, The Atlantic, February 1962.) In other words the Loyalists were to the winners reactionary imperialists—an unpopular group when the Republic was in process of formation, and at least equally a term of reproach among the emergent nations of Asia and Africa in our own day. 11 The Pioneer Farmer and Backwoodsman the real and unqualified Loyalists. Later governors authorized additions to the list in the interest of attracting settlers. These are sometimes called 'late Loyalists',* but contemporary set-tlers from Great Britain and Ireland and the writers of travel books describe them variously as American Loyalists, Ameri-cans, United English Loyalists, and Yankees. In 1822 Robert Gourlay referred to them as 'Loyalists of the United Empire', but others used terms of opprobrium such as 'Yankee land-grabbers' and 'skedadlers', and charged that many of them left the United States to evade their debts or, a little later, to avoid service in the War of 1812. But it must be remembered that many of these charges were levelled against them by those used to British aristocratic government, to whom they were demo-crats, republicans, or (in the fashion of our day) communists. The official class in the American colonies provided one section of Loyalists who acted from a mixture of duty, fidelity, bias, and self-interest; and there were a few large landed pro-prietors who were loyal because they were aristocratic, who were not rebels because the established order best served them. - eBook - PDF

American Revolution

People and Perspectives

- Andrew K. Frank(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

“Allegiance to a Fall’n Lord”: The Loyalist Experience in the American Revolution Margaret Sankey 12 riting to his friend Thomas McKean in 1814, John Adams guessed that a third of Americans during the Revolution were for the rebel- lion, a third neutral, and a third Tories, or supporters of the continu- W ation of British rule. For a population of 2.5 million colonists in 1776, more modern estimates of 500,000 men and women who gave some sign of loy- alty to George III and as many as 80,000 who went into exile for that choice may be more accurate. In comparison to the French Revolution, whose well- known exodus of ci-devant aristocrats may have been 5 per 1,000 citizens, R. R. Palmer suggested the American Loyalists were a far greater propor- tion, at 24 per 1,000. Whatever their numbers, the existence of counter- Revolutionaries and their experience provides a crucial lens through which to view the American Revolution, which was far from universally popu- lar. Vilified and painted as enemies by both their contemporaries and later Whig histories of the period, Tories clung fast to their principles of loyalty and empire, deeply shocked at being labeled “disaffected” or “a party.” For these British subjects, it was the rebels who had strayed from the path into a faction, imperiling their Anglo-American world (Adams, 1856, 10:87; Evans, 1969, 3; Palmer, 1959, 1:187–189; Norton, 1972, 9; Ritcheson, 1973, 5; Ouster- hout, 1987, 4). Tories and Critics Ironically, in the years before 1776, the men who were later identified as Tories were some of the most insistent critics of British imperial policy, be- lieving that in their capacity as good subjects, they had not just the right, but the duty to supply the ministry with good information and corrections to their reading of the American situation. The 1765 Stamp Act met with almost universal disapproval, even among officers appointed by the king. - eBook - ePub

The War for Independence and the Transformation of American Society

War and Society in the United States, 1775-83

- Harry M. Ward(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Most estimates place one-third of Americans as loyalist, one-third on the fence, to be swayed by whomever was winning, and one-third rebel. Persons who decided to adhere to Great Britain faced ostracism, confinement, civil disabilities, and, on rare occasion, death. The easiest way to avoid detection and punishment was to take the patriot loyalty oath, which could be rationalized as a temporary expedient. If willing to keep to themselves, giving an appearance of being neutral and not aiding the enemy in any way, Loyalists experienced relative unmolestation. For overt committal to the British cause there was but little recourse than to flee behind British lines or go into exile.Choosing Sides

Throughout the colonies a variety of Americans had a predilection to side with the British cause. Individuals committed themselves out of conviction or self or group interest. A quantitative study of personal traits finds certain determinants. In comparison to the revolutionaries, Loyalists tended to be older, members of the Anglican Church, more wealthy, holders of better jobs, residents of the east coast who depended on their livelihood from their connections with Great Britain, those who expected gain or protection from crown authority, those who had operations or dealings outside a colony, recent immigrants, those better educated and traveled, those more cosmopolitan in outlook, and those authority-and-order oriented.3 Yet Loyalists came from all walks of life. In Massachusetts, for example, of 300 persons banished in 1778, one-third were professionals, gentlemen, and merchants; one-third farmers; and one-third artisans, laborers, and a few shopkeepers.4 Benjamin Rush, in 1777, differentiated Loyalists according to conduct:There were (1) furious Tories who had recourse to violence, and even to arms, to oppose the measures of the Whigs. (2) Writing and talking Tories. (3) Silent but busy Tories in disseminating Tory pamphlets and newspapers and in circulating intelligence. (4) Peaceable and conscientious Tories who patiently submitted to the measures of the governing powers, and who showed nearly equal kindness to the distressed of both parties during the war… .5While Loyalists were everywhere, they were more concentrated in certain locales, usually in an urban context. Most New Hampshire Loyalists were in Portsmouth. In Massachusetts, most were found in the Boston area, a good many of whom were wealthy merchants, whom Anne Hulton described as too “terrified to submit to the Tyranny of that Power they at first set up.”6 - eBook - ePub

A War of Ideas

British Attitudes to the Wars Against Revolutionary France, 1792–1802

- Emma Vincent Macleod(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The claim that there was a remarkable surge of popular loyalism in the 1790s is not nullified, as some historians have suggested, by the economic tensions of the decade which ensured that general public opinion was unreliable as a source of government support. 5 Loyalists were, by definition, committed activists, at least for part of this decade, if not in all cases for all of it. They sought to defend whatever benefits—political, economic, religious or moral—they perceived the present social order to have conferred upon them against the common menace of Jacobinism and its British sympathisers. 6 French egalitarian principles threatened the British social and political hierarchy which, since they protected private property, Loyalists believed to be advantageous to all but the very bottom ranks of society. These principles were also regarded as being hostile to the Established Churches in Britain and to the Christian religion itself, which upheld the political and social system and consoled those who were least well-off under it. Loyalists, watching events across the Channel, also judged them to be destructive of public order and morality. From the time of the royal proclamation against seditious literature of May 1792, Loyalists began rallying to support the government against domestic radicalism, by means of addresses, letters, pamphlets, newspaper articles and the establishment of hundreds, if not thousands, of Loyal Associations from 20 November 1792. 7 The Loyalists had risen, almost wholly without government intervention, because of the threat to the constitution posed by British radicalism, and they were further galvanized and propelled into the public arena by the exponential increase of the domestic threat caused by French events - David Armitage, Sanjay Subrahmanyam(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Red Globe Press(Publisher)

Investigating these migrations side by side also holds larger implications for interpreting the turbulent Age of Revolutions in which they took place. At the beginning of his magisterial study of England in the Age of Revolutions,E.P. Thompson opined that too often ‘the blind alleys, the lost causes, and the losers themselves are forgotten’ by historians. 4 His complaint aptly describes the historiographical fate of Loyalists and émigrés. Neither group has earned much place within the sprawling literatures on the American and French revolutions, and for analogous reasons. Within United States historiography, the relative absence of Loyalists serves as an illustration of what happens when history is written by the victors. Loyalists are at best fringe players in canonical narratives of the nation’s founding. Though several scholars have studied loyalist ideology and profiled leading Loyalists, the social extent and diversity of loyalism remain less well understood, and the individual experiences of ordinary Loyalists have been little explored.As a result, Loyalists are often stereotyped in America as socially elite, politically reactionary, and essentially ‘un-American’ – conservatives who stubbornly failed to recognize that the future lay with the republic, not the British Empire. (They are still widely referred to as ‘Tories’, a label pejoratively applied to them by American patriots, though their political opinions ranged more widely than that term suggests.) It has become a commonplace to acknowledge certain contradictions embedded in the new republic: its self-contradictory commitment to slavery, and its hostility towards American Indians. But the flight of the Loyalists calls attention to a form of exclusion that has yet to be incorporated into US national self-understandings, an exclusion rooted in political belief.- eBook - PDF

Ulster Loyalism after the Good Friday Agreement

History, Identity and Change

- J. McAuley, G. Spencer, J. McAuley, G. Spencer(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

8 Chapter 1 Historic Loyalism: Allegiance, Patriotism, Irishness and Britishness in Ireland Thomas Hennessey In Ireland the term ‘loyalism’ has been deployed in many guises – too many in fact. In the late twentieth century, by the climax of the conflict known as the Troubles, the term came to embody anyone who was part of, or linked with, Protestant organizations that used pro-state terrorism against Roman Catholics in Northern Ireland. But, less than a generation earlier, the term could equally apply to those who were ‘traditional unionists’ and opposed the reformist policies of Stormont governments. In this way the Reverend Dr Ian Paisley began political life as a ‘loyalist’ before entering the electoral mainstream and becoming a ‘unionist’. Yet, away from the definitional muddles of contemporary Northern Ire- land, loyalism has been, at its core, a loyalty to the Crown: but, not neces- sarily the British Crown, rather the English Crown, the Irish Crown and, finally, the British Crown. This allegiance formed the basis the very of basis of not merely Irishness, but Englishness and, later, Britishness, itself. And, in Ireland, it was a key element of nationalist identity as well as unionist identity. Loyalism in Irish history The basis of historic loyalism is the fact that the Kingdom of Ireland and its successors (the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) were, and are monarchical states. Republicanism was an alien form of government introduced into Ireland in 1798; indeed it was a minority sport until 1916. - eBook - ePub

For King, Constitution, and Country

The English Loyalists and the French Revolution

- Robert Dozier(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

CHAPTER IVTHE Loyalists AND THE COLD WAR

On December 9, two weeks before the wave of enthusiasm for founding new societies crested, the Observer optimistically commented that the loyal movement had, “in the course of ONE WEEK, triumphed over the evil machinations of a dangerous and deluded faction, which was too long permitted to disgrace this country.”1 Making allowances for the prematurity of the opinions of the Observer’s lead writer, to a degree he was correct. A victory of sorts was in the making, and before December was out, was rapidly turning into a rout of the enemy. Practically every person active in the political community of England was joining the ranks of the Loyalists. Even Charles James Fox seconded a loyal address at St. George’s Parish. If this kind of activity was the antidote to the “French poison,” a large dose had been administered to the English body politic, and only time would reveal whether or not the patient was on the mend.Moreover, the Loyalists revealed themselves by standing up for the constitution. By all precedents (and consequents, as well) this was an unusual occurrence. Normally, it is the discontented, those who desire change, who speak loudest and are more noticed by historians. In this instance, those who were normally not heard of, those who were satisfied with things as they were and who generally did not have anything to complain of were the chief actors. The loyal movement offers us a rare opportunity to examine the thoughts and to analyze actions and their effects in a different section of society, differently motivated and with different goals. In addition, because the Loyalists were the ultimate victors in the struggle, their influence upon the subsequent course of English history was of greater importance than that of their defeated opponents, and a study of them is imperative for any understanding of what was to transpire in the future.There are limitations to such a study. The chief sources of information about the Loyalists are their declarations and resolutions, either collected by Reeves or published in local newspapers. These relate to but a single event. Loyal activities were only occasionally noted by newspapers or were revealed only in the few minutes forwarded to Reeves. The records of the original society in London are fairly complete but should not be taken as representing the whole movement. In spite of this paucity of information, some definite answers about the Loyalists in general can be ascertained. It is possible, for instance, to know to some degree who they were, why they joined the movement, their chief goals, and some of their methods of achieving them. It is also possible to state with some certainty what they failed to do and what they had no intention of doing. - eBook - ePub

Dishonored Americans

The Political Death of Loyalists in Revolutionary America

- Timothy Compeau(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- University of Virginia Press(Publisher)

40 In general, Loyalist narratives and memorials present a few recurring personas. Some Loyalists portrayed themselves as refined martyrs who were set upon by the unruly, unwashed mob. Other Loyalists depicted themselves as wily foxes that had outwitted the ham-fisted agents of Congress. The most gripping Loyalist narratives went beyond the templates and showcased adventurous men with the requisite blend of strength and sensibility thought to be possessed by the first class of gentlemen. Regardless of how they presented themselves, the Loyalists intended to demonstrate how deeply unfair it was that such honorable men were so badly used.Loyalist authors rarely missed an opportunity to indulge their nostalgia and recount the ideal colonial world of the country gentleman that the Revolution destroyed. James Moody was “a happy farmer, without a wish or an idea of any other enjoyment, than that of making happy, and being happy, with a beloved wife, and three promising children.” He was a moral and independent family man “clear of debt, and at ease in his professions.” Joel Stone, from a more modest background, was a farmer’s son turned successful trader in partnership with “a Merchant of great trade.” His dignity and work ethic were visible in the “confidence and esteem of all my Neighbours and the public in general.” No retired gentleman, Stone was building his fortune, and “by dint of an unwearied diligence and a close application to trade I found the number of my Friends and customers daily increasing and a fair prospect of long happiness arose to my sanguine mind.”41 Both John Connolly and John Peters wrote of their advanced education—Peters attended Yale, and Connolly “received as perfect an education as that country could afford.” Wherever these two settled on the frontier, civilization seemed to spring up around them. Connolly helped establish new settlements in western Virginia and valiantly assisted Lord Dunmore in his war with the Shawnee in 1774. Peters left Connecticut for New Hampshire, where he established mills and farms, and then moved west to New York and was “appointed by Governor Tryon to be Colonel of the Militia, Justice of the Peace, Judge of Probates, Register of the County, Clerk of the Courts; and Judge of the Court of Common Pleas: Here I was in easy circumstances, and as Independent as my mind ever wish’d.”42 - eBook - PDF

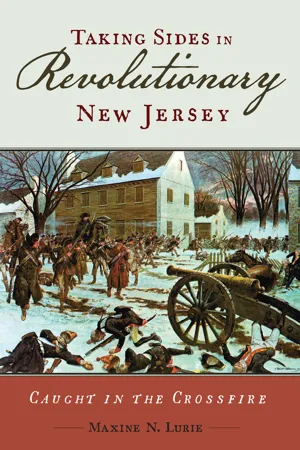

Taking Sides in Revolutionary New Jersey

Caught in the Crossfire

- Maxine N. Lurie(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Rutgers University Press(Publisher)

158 7 Loyalists Part II Remained or Returned The stories of Loyalists who remained are diverse, some very interesting, but most others are lost to us. Like the exiles as well as Patriots and Quakers, in this nasty civil war, at times they paid a significant price for their loyalty. They were caught in British, Hessian, Loyalist, and Patriot raids. Their property was damaged, destroyed, and confiscated.1 Yet, as noted in chapter 6, in the end most Loyal- ists remained and some later returned. A few discussed here used the money they obtained from the Royal Loyalist Claims Commission to purchase prop- erty in the United States (rather than staying in England or departing for Can- ada or elsewhere). Others tried to reclaim their lost property or just started over. Of course, slaves who sympathized with the British, or fought for them, had no choice if they ended up in Patriot hands—they stayed. Those who were part of forfeited estates were usually sold to new masters. Sadly, some who were prom- ised their freedom in return for serving in their master’s stead, were cheated out of their goal (see the previous discussion of Patriot Blacks in chapter 2). The sto- ries of those who remained or returned after the Revolution are sometimes unexpected, with family ties often part of the explanation. Remained Abraham Beach There were an estimated eleven Anglican clergymen in New Jersey in 1775, but only four in 1783, with just two of those ministering (Abraham Beach and Uzal Loyalists Part II: Remained or Returned • 159 Ogden). Apparently, just the Reverend Abraham Beach (1740–1828) in New Brunswick, with whose story this book began, stayed throughout the war. Beach was born in Connecticut, graduated from Yale in 1757, and then after several years felt the call of religion. He traveled to England, where he was ordained in 1767, returned, and under the direction of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG) served congregations in New Brunswick and nearby.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.