History

March on Washington

The March on Washington was a historic civil rights demonstration that took place on August 28, 1963, in Washington, D.C. It was organized to advocate for civil and economic rights for African Americans and included Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous "I Have a Dream" speech. The march is widely recognized as a pivotal moment in the American civil rights movement.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "March on Washington"

- eBook - PDF

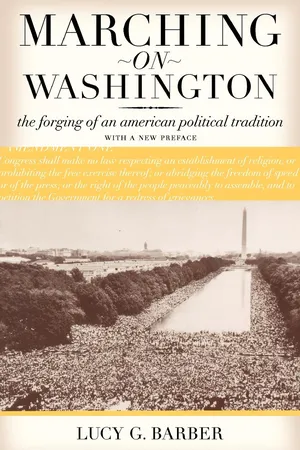

Marching on Washington

The Forging of an American Political Tradition

- Lucy G. Barber(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER FIVE IN THE GREAT TRADITION The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, August 28, 1963 On August 28, 1963, more than 2oo,ooo protesters converged on the na-tion's capital for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Not long after, Tom Kahn, an organizer for the protest, tried to assess the day's significance. As Kahn emphasized, the marchers had come to Washington as the result of hard-won agreement among leaders of civil rights, religious, and labor groups to sponsor a massive, peaceful demon-stration in Washington. The participants had heard of the march because of its effective and unprecedented mass marketing. They also had the un-precedented blessing of President John F. Kennedy. Assembling on the hill around the Washington Monument, the participants marched to the Lincoln Memorial, where they listened to speeches from the protest's leaders. In his assessment, Kahn was unsure whether the march would achieve its stated goals: a strong civil rights bill and measures to reduce unemployment. About one thing, however, he was sure: The success of the March on Washington is now a part of American history. 1 Kahn was right about the historic nature of the March on Washing-ton. It is both the most familiar and most remembered protest in the United States. Pictures of the marchers gathered at the Lincoln Memo-rial cover history textbooks. Clips from Martin Luther King Jr.'s I have a dream speech are featured in television commercials. 2 And the march often served as the explicit model for subsequent demonstrations. The pervasiveness of this march in popular memory emerged from the con-scious effort by organizers and government officials to ensure that the 141 142 IN THE GREAT TRADITION demonstration would be acceptable to the general public. In the process, the protest helped legitimate a new kind of March on Washington in American political culture. - eBook - PDF

A History of Hope

When Americans Have Dared to Dream of a Better Future

- NA NA(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

C HAPTER T EN T HE C IVIL R IGHTS M OVEMENT “I H AVE A D REAM ,” 1963 THIRTY YEARS AFTER A. PHILIP RANDOLPH first proposed a March on Washington, and one hundred years after Abraham Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation, on August 28, 1963, over 200,000 Americans marched in the nation’s capital and then stood in front of the Lincoln Memorial to hear the speeches. The keynote address of the March on Washington for Civil Rights was delivered by Martin Luther King Jr., already the nation’s most charis- matic and respected leader of the civil rights movement. In words that have be- come immortal, King declared his hope for America. “Go back to Mississippi; go back to Alabama; go back to South Carolina; go back to Georgia; go back to Louisiana; go back to the slums and ghettos of the northern cities,” King told the marchers, “knowing that somehow this situation can, and will be changed. . . . Let us not wallow in the valley of despair,” he said. Hope was coming. So I say to you, my friends, that even though we must face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed—we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal. King knew that the dream would need to become a reality in some of the na- tion’s most difficult places; in Mississippi, “a state sweltering with the heat of in- justice,” and in Alabama, “with its vicious racists.” Yet it was right there in places 250 A HISTORY OF HOPE like Mississippi and Alabama that King believed that, “little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” That was his hope and his dream. - eBook - PDF

In a New Century

Essays on Queer History, Politics, and Community Life

- John D’Emilio, John D'Emilio(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University of Wisconsin Press(Publisher)

2 (March–April 2005): 33–34. The 1979 March on Washington 191 assessing the meaning of Brown v. Board of Education on its fiftieth anni- versary. Audiences sat in university lecture halls, community meeting spaces, and houses of worship to think about the struggle for racial justice. Commemorations like this can propel change in the present, as individuals draw lessons from the victories and struggles of the past. So it is important that we are taking time today to recall the 1979 March on Washington on its twenty-fifth anniversary. However, the more I have thought about what I want to say, the more I have found myself skeptical that the march is anything more than a foot- note in history. This is perhaps a heretical comment to make on a panel like this, but maybe I can illustrate my doubts by comparing the 1979 event with two other famous marches: • In August 1963 approximately 250,000 people from every part of the country assembled in Washington for an event that has become so iconic that we often simply refer to it as “the March on Washington.” The march was a major story in every news out- let of consequence in the United States. Large national organiza- tions with membership in the hundreds of thousands—indeed, in the millions—backed the venture. In the months before the march, local demonstrations erupted in hundreds upon hundreds of communities around the country. President Kennedy sent national civil rights legislation to Congress. Agitation for racial equality was at such a high level that it took only seven weeks for organizers to pull such a large crowd to Washington. In other words, continuing agitation for black freedom, a national infra- structure of organizations, and a realizable national goal together made it a strategic time to March on Washington. • In November 1969 more than 400,000 Americans gathered in Washington to protest the Vietnam War. - eBook - PDF

Icons of African American Protest

Trailblazing Activists of the Civil Rights Movement [2 volumes]

- Gladys L. Knight(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Tensions mounted when some blacks (not associated with the campaign) rioted in a park. Connor 304 Icons of African American Protest ordered his men, decked in steel helmets that displayed the Confederate flag, to intimidate the activists. But King knew that his strategy was working. For one thing, he had again attracted the media’s attention. And finally, King successfully pressured Attor- ney General Kennedy to intervene and press city officials into negotiations. These officials eventually consented to negotiations with Andrew Young, one of King’s advisors, and a pact was constructed to King’s satisfaction. Angry whites set off bombs in Birmingham in protest. But the success in Birmingham helped pave the way for the most far-reaching legislation since Emancipation: the Civil Rights Act of 1964. It also magnified King’s popularity and put him on the front cover of Time as the ‘‘Man of the Year.’’ March on Washington FOR JOBS AND FREEDOM The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which took place on Au- gust 28, 1963, was a climactic moment for the Civil Rights Movement. Ini- tiated by A. Philip Randolph, from the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and Bayard Rustin, a peripatetic activist, the March drew 250,000 people to the nation’s capitol to hear the Big Six from the Civil Rights Movement: James Farmer (Congress of Racial Equality), John Lewis (SNCC), Roy Wil- kins (NAACP), Whitney Young (National Urban League), Dorothy Height (National Council of Negro Women), and King (SCLC). Not a heart was unmoved when King mounted the podium and gave his most memorable speech, ‘‘I Have a Dream.’’ President Kennedy, who had originally protested the march (thinking a riot would ensue), was also moved. He gave impetus to the day by making the public announcement that civil rights legislation was in the works. But Kennedy would not have the opportunity to see his work completed, for he was assassinated on November 22, 1963. - eBook - PDF

American Voices

An Encyclopedia of Contemporary Orators

- Bernard K. Duffy, Richard Leeman, Bernard K. Duffy, Richard Leeman(Authors)

- 2005(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

The Kennedy administration's approval ratings had fallen, and losing the fight in Congress could damage a number of other programs. King spent much of the summer speaking coast to coast, riding the victory in Birmingham and pressing forth the cause. In a speech he de- livered at the close of a Freedom Walk in Detroit in June 1963, King anticipated the more mo- mentous March on Washington and also re- hearsed many of the most potent passages of "I Have a Dream." He spoke emphatically about the importance of continued "determined pressure" to achieve the passage of Kennedy's civil rights bill: "In order to put this bill through, we've got to arouse the conscience of the nation, and we ought to march to Washington more than 100,000 ... to engage in a nonviolent protest." In Detroit he said, as he would say in Washington, that 100 years after the Emancipation Proclama- tion, "the Negro in the United States still isn't free." As in Washington, he expressed his appre- hension that the movement would lose its mo- mentum. Sensitive to the dynamics of social movements, King cautioned against heeding "cries saying, 'Slow up and cool off.'" "There is," he joked, "always the danger if you cool off too much that you will end up in a deep freeze." The famous "dream" section, prefigured in his speech to the AFL-CIO, found even more con- crete and poetic form in the Detroit address. King's speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial represented the apotheosis of his or- atory. He addressed a throng of more than 200,000 people of every race who had gathered to press for the passage of the historic legisla- tion that would transform a nation rent by racial tensions and embarrassed by the bigotry and pa- ternalism that had been institutionalized in much of the South but existed de facto in every corner of the country. King's memory is fixed by this important, though often uncritically mythologized, speech. - eBook - ePub

The Speech

The Story Behind Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s Dream

- Gary Younge(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Haymarket Books(Publisher)

The historical importance of epoch-defining events like the March on Washington is rarely fully apparent at the time. It is only with the benefit of hindsight that they emerge as emblematic. Yet there was a broad consensus that day that something fundamental and consequential had occurred. Whatever ramifications the march might have for legislation or the movement, the very fact it had taken place, passed without violent incident, and been witnessed by millions was enough. “We’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition,” King said in his speech. This was one act America was never going to forget.Karl Marx wrote in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte :Men make their own history. But they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language.So it was with the March on Washington, which was both bold in its conviction and old in its conception. Bold because national demonstrations in America’s capital were rare at the time. “Marches on Washington have become ritualized dramas, carefully scripted and with few surprises,” writes John D’Emilio inLost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin. “In the decades [since the 1960s] virtually every cause, every constituency, every identity group has descended on the nation’s capital, paraded through its streets, and assembled on the vast Mall to hear an array of speakers and entertainers. . . . This was not the case in 1963. Then the idea was . . . fresh and untried. No one had ever witnessed a mass descent on the nation’s capital.”And it was old because the original idea for such a march had been hatched more than twenty years earlier, by the Black union and civil rights leader Asa Philip Randolph. In 1941 Randolph had called for a March on Washington against discrimination in the defense industry and segregation in the military. “The virtue and rightness of a cause are not alone the condition and cause of its progress and acceptance,” he had argued when announcing the protest. “Power and pressure are at the foundation of the march of social justice and reform. . . . Power and pressure do not reside in the few, and the intelligentsia, they lie in and flow from the masses.” The march was to be Black only. “There are some things Negroes must do alone,” said Randolph. “This is our fight and we must see it through.” - eBook - ePub

Equal Time

Television and the Civil Rights Movement

- Aniko Bodroghkozy(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- University of Illinois Press(Publisher)

46 For a few significant hours, the agenda of a grassroots movement for the empowerment of the disenfranchised and oppressed took over the airways, with TV reporters serving largely as masters of ceremony, sharing in the celebration of consensus.Dayan and Katz provide three basic typologies of media events: contest, conquest, and coronation. The March on Washington was scripted largely as a conquest—the celebration of a charismatic hero struggling against huge odds to bring about significant change. This script emphasizes the primacy of the individualized hero much more than we see in March on Washington coverage, although Dayan and Katz’s typology allows for “collective protagonists.”47In popular memory, of course, the march has become inextricably linked to the figure of Martin Luther King as hero and to King’s “dream” of a world remade. Today, the march is remembered mostly as being about King, with the 250,000 marchers serving largely as audience or backdrop for his charismatic address. This was not how the networks covered the march on August 28. King was not the star of the show: the marchers were the “collective protagonists” along with all the speakers up on the podium, including King. King was in no way privileged. Reporters and commentators did not anticipate his speech or engage in any suspense-building discussion about King’s place in the schedule of events. In this particular version of the “conquest” script, the multitudes accompanying their leaders into the potentially hostile arena were as significant, if not more so, than any charismatic leader. Together with King and the other speakers on the podium at the Lincoln Memorial, they all enacted a script of battle-tested (peaceful) warriors making their pilgrimage to the seat of national power and, against all odds, using the force of their numbers and their collective charismatic quality both to change the world and also to provide a vision of what that changed world would look like. - eBook - PDF

Reframing 1968

American Politics, Protest and Identity

- Martin Halliwell, Nick Witham(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Edinburgh University Press(Publisher)

NINE 1968: End of The Civil Rights Movement? Stephen Tuck On Sunday 7 April 1968 the United States held a national day of mourning for the Reverend Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. In New York City that afternoon some 5000 people marched from Harlem to Central Park to join an open-air memorial service to commemorate the civil rights leader who had been murdered in Memphis three days earlier. The march was sombre and subdued. In a show of solidarity, Charles Kenyatta, leader of Harlem’s Mau Mau group, walked arm in arm with New York’s Governor Nelson Rockefeller. One man at the front of the march held a large picture of Malcolm X. The woman next to him carried a smaller picture of Martin Luther King. As the platform party made its way to the stage, James Forman, a prominent student leader, stood up on his seat in the front row and called on Rockefeller to tell the president to ‘Free Rap Brown’, the high profile Black Power leader who was on hunger strike to protest his imprisonment on the charge of threatening the life of an FBI officer. 1 Forman was joined by colleagues who each had a picture of Brown pinned to their chests. As the African American newspaper, the New York Amsterdam News put it, Forman brought the tribute to King ‘to a halt even before it began’. 2 Forman stopped his pro-tests when Kenyatta invited him to join the speakers on the stage. Rockefeller, speaking first, compared Martin Luther King to Jesus Christ, a man who gave his life ‘so we may live in brotherhood ourselves’. The following day, the governor would ask the state legislature to agree legislation to fund urban regeneration projects, Not for distribution or resale. For personal use only. 206 / Reframing 1968: American Politics, Protest and Identity including a $10 million office in Harlem to be named the ‘Dr. Martin Luther King State of Office Building’. 3 While the main tribute was in Harlem and Central Park, there were parades across the city in memory of King. - eBook - ePub

The Other Special Relationship

Race, Rights, and Riots in Britain and the United States

- R. Kelley, S. Tuck, R. Kelley, S. Tuck(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

31 Shortly following Baker’s remarks, film actor Burt Lancaster took to the podium with a scroll of over 1500 names of Americans in Paris who had signed the petition that had circulated in papers throughout Europe in response to James Baldwin’s push for international support of the March on Washington. Although the Paris committee of supporters chose to forego plans to stage a march in Paris, electing instead to demonstrate their solidarity through a collective presentation of their petitions on the afternoon of August 21, 1963, the idea of protesting the second-class citizenship of Black Americans at the thresholds of monuments of American political power would be a theme of the March on Washington movement that would not be lost on international audiences.In the wake of reports that hundreds of protestors organized under the auspices of the multinational African Association were planning a demonstration at the American Embassy in Cairo on the day of the March on Washington, Egyptian officials dispatched over two hundred officers to control the demonstration and prevent protestors from directly surrounding the Embassy so that any “possible embarrassment to U.S.-U.A.R. relations” could be avoided.32 Although only 13 people participated in the march carrying signs displaying such slogans including “Remember Negroes Also Built America,” “Down With US Imperialism,” and “Medgar Evers Did Not Die in Vain,” police intercepted protesters one block away from the embassy and selected two delegates to present their petition to embassy officials.33 Representing nationalist movements in 11 African nations including South Africa, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, and Kenya, the petition, which an embassy official described as being riddled with “Commie-lining phraseology,” railed against the Kennedy Administration “for its pretensions at helping the Negro people” and condemned the “atrocities and barbarities” on display in places like Birmingham, Alabama, “against a people whose only sin is being black, and demanding equality and the enjoyment of elementary human rights.”34 - eBook - ePub

Bearing the Cross

Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

- David J. Garrow(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Open Road Media(Publisher)

Despite this success, painful tensions had arisen between ACMHR and SCLC concerning the two organizations’ intertwined financial relationship. ACMHR Treasurer William E. Shortridge complained to Fred Shuttlesworth that their organization was not receiving a fair share of the monies that SCLC was reaping in the wake of the protests. Because Shuttlesworth gave little heed to his repeated complaints, Shortridge took them to SCLC Treasurer Abernathy, explaining that ACMHR had received little income since late May and bills were piling up, especially those from the attorneys and bonding companies that had helped secure the release of the hundreds of demonstrators. Shortridge acknowledged that SCLC had passed along two checks totaling $14,000, but ACMHR was in the red and required further support. King also listened sympathetically to Shortridge during his June 20 visit, but the issue remained a problem throughout the summer.At that evening’s ACMHR mass meeting, King talked about the upcoming pilgrimage to the nation’s capital and how it would put pressure on Congress to pass the civil rights bill that John Kennedy had sent to Capitol Hill just the day before. “As soon as they start to filibuster,” King declared, “I think we should March on Washington with a quarter of a million people.” The next morning, March coordinators Cleveland Robinson and George Lawrence announced plans for the protest to the New York press. The purpose of the mass demonstration, Robinson emphasized, would be to draw national attention to the problem of black unemployment and the need for thousands of new jobs, and not simply to lobby for civil rights legislation.45Within hours of Robinson’s announcement the Kennedy White House summoned the black leadership to a meeting the following day with the president. When the session convened, John Kennedy explained what it would take to win congressional approval of the administration’s bill. The most difficult hurdle would be to obtain cloture in the Senate; for that, the votes of many midwestern Republicans who usually took little interest in racial issues would be necessary. The proposed March on Washington might hinder rather than help the effort to gain those votes. “We want success in Congress,” Kennedy stated,not just a big show at the Capitol. Some of these people are looking for an excuse to be against us. I don’t want to give any of them a chance to say, “Yes, I’m for the bill but I’m damned if I will vote for it at the point of a gun.” It seemed to me a great mistake to announce a March on Washington before the bill was even in committee. The only effect is to create an atmosphere of intimidation—and this may give some members of Congress an out.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.