History

March to Selma

The March to Selma refers to the series of civil rights marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965. Led by activists including Martin Luther King Jr., the marches aimed to protest racial discrimination in voting rights and to demand equal access to the ballot box for African Americans. The marches ultimately led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "March to Selma"

- eBook - PDF

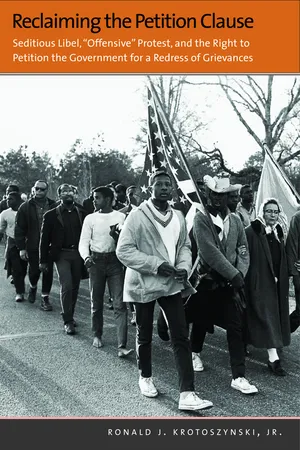

Reclaiming the Petition Clause

Seditious Libel, ',Offensive', Protest, and the Right to Petition the Government for a Redress of Grievances'

- Ronald J. Krotoszynski(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

185 6 T HE S ELMA -TO -M ONTGOMERY M ARCH AS AN E XEMPLAR OF H YBRID P ETITIONING At times history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama. —President Lyndon B. Johnson, March 15 , 1965 The iconic Selma-to-Montgomery march, of March 21 to 25 , 1965 , provides an example of precisely how advocates of legal change can and do exercise their expressive freedoms conjunctively, and for the need for the federal courts to consider the implications of petitioning in the context of speech, assembly, and association. Almost fifty years ago, five days in March helped to begin a new era for the South, and for the nation. From March 21 to March 25 , 1965 , thousands of civil rights protesters marched down U.S. Highway 80 from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to call attention to the state’s systematic disenfranchisement of African American citi-zens. Then as now, Highway 80 was a main regional corridor, connecting Selma and Montgomery with points east and west, symbolically linking Alabama’s denial of the right to vote with similar abuses throughout the South. The Selma march represents a high-water mark for the vindication of expressive freedoms, notably including the right of petition, and the democratic values these rights embody. In the words of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., “Selma, Alabama became a shining moment in the conscience of man.” 1 The social significance of the Selma march is well documented. 2 By focusing national attention on the disenfranchisement of Southern blacks, it prompted Congress to pass one of the most sweeping civil rights laws in history: the Voting Rights Act of 1965 . 3 The Voting Rights Act, in turn, led to a dramatic rise in - eBook - ePub

The Civil Rights Movement

A Documentary Reader

- John A. Kirk(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

SEC. 5. Whenever a State or political subdivision with respect to which the prohibitions set forth in section 4(a) are in effect shall enact or seek to administer any voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting different from that in force or effect on November 1, 1964, such State or subdivision may institute an action in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia for a declaratory judgment that such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure does not have the purpose and will not have the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race or color, and unless and until the court enters such judgment no person shall be denied the right to vote for failure to comply with such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure: Provided, That such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure may be enforced without such proceeding if the qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure has been submitted by the chief legal officer or other appropriate official of such State or subdivision to the Attorney General and the Attorney General has not interposed an objection within sixty days after such submission, except that neither the Attorney General’s failure to object nor a declaratory judgment entered under this section shall bar a subsequent action to enjoin enforcement of such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure. Any action under this section shall be heard and determined by a court of three judges in accordance with the provisions of section 2284 of title 28 of the United States Code and any appeal shall lie to the Supreme Court.Approved August 6, 1965.Source: US Congress, Voting Rights Act of 1965, http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?doc=100&page=transcriptDiscussion Questions

- What does the Selma campaign tell us about the advantages and disadvantages of Martin Luther King, Jr’s prominent national profile in the civil rights movement?

- Why did King choose to defy a federal court order to hold a second march from Selma to Montgomery? Was he right to do so?

- Assess the significance of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s use of the movement’s refrain “We Shall Overcome” in his remarks to Congress.

Further Reading

- Combs, Barbara Harris. From Selma to Montgomery: The Long March to Freedom(Routledge, 2014).

- Ellis, Sylvia. Freedom’s Pragmatist: Lyndon Johnson and Civil Rights(University Press of Florida, 2013).

- Garrow, David J. Protest at Selma: Martin Luther King, Jr, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965(Yale University Press, 1978).

- Garrow, David J. The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr: From “Solo” to Memphis(W.W. Norton, 1981).

- Lawson, Steven F. Black Ballots: Voting Rights in the South, 1944–1969(Columbia University Press, 1976).

- May, Gary. Bending toward Justice: The Voting Rights Act and the Transformation of American Democracy(Basic Books, 2013).

- O’Reilly, Kenneth. Racial Matters: The FBI’s Secret File on Black America, 1960–1972(Free Press, 1989).

- Stanton, Mary. From Selma to Sorrow: The Life and Death of Viola Liuzzo(University of Georgia Press, 1998).

- Thornton, J. Mills. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma(University of Alabama Press, 2002).

- Webb, Sheyann, and Rachel West Nelson. Selma, Lord, Selma: Girlhood Memories of the Civil Rights Days

- eBook - ePub

- Jim Willis, Mark Miller(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

Chapter 9Selma (2014)The Edmund Pettus Bridge in south-central Alabama was stained by violence on one “Bloody Sunday” in March 1965. When 500-some unarmed Black citizens marched across the bridge on Route 80, chaos erupted as local police troopers met the peaceable demonstrators with a brutal onslaught. The victims of that day’s savage display of racism comprised a group of Black activists assembled under the leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during a critical moment in the civil rights movement. The decisive campaign centered on the ability of African American citizens in Selma, Alabama, to secure equal voting rights, and the protest took on the form of a 54-mile march from Selma to Montgomery. The 2014 film Selma takes viewers back to the three months in which the action took place, following King (David Oyelowo) as well as his activist colleagues James Bevel (Common), Hosea Williams (Wendell Pierce), and John Lewis (Stephan James).Following his personal triumph on receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, Norway, King returns to American soil to confront the trying circumstances that compel him to visit southern territory. After holding conversations with President Lyndon Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) that can only go so far, King resorts to the only strategy he knows will work: use nonviolent protests as a platform for social reform while intentionally eliciting racist backlash—all while the TV cameras are watching. Though they recognize the high likelihood of physical harm ahead of them, the tight-knit band of civil rights leaders consider the risk well worth taking, as the stakes are high with the entire nation increasingly embroiled in conflicts linked to racial discrimination. King’s fervor—and the nation backing him—would lead thousands to join the cause and march the road from Selma toward historic legislative action that same year. - eBook - ePub

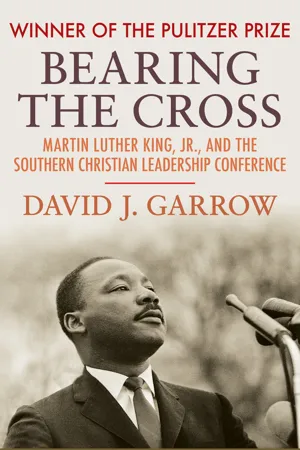

Bearing the Cross

Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

- David J. Garrow(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Open Road Media(Publisher)

“Selma was bigger than Birmingham, though it was smaller in scope, because for the first time whites and Negroes from all over the nation physically joined the struggle in a pilgrimage to the deep south. This was a new level of commitment because it entailed danger and continuity. But more important, the elements who responded were for the first time a true cross-section of America,” a much broader coalition of support for the movement than ever before. Such a development presented King with both opportunities and dangers, Levison counseled. “Selma and Montgomery made you one of the most powerful figures in the country — a leader now not merely of Negroes, but of millions of whites.” The civil rights movement was “one of the rare independent movements” America had seen, “and you are one of the exceptional figures who attained the heights of popular confidence and trust without having obligations to any political party or other dominant interests. Seldom has anyone in American history come up by this path, fully retaining his independence and freedom of action.” That position was all the more influential, Levison told King, because “the movement you lead is the single movement in the nation at this time which arouses the finer democratic instincts of the nation.” While “there is a sense of shame people feel over the rampant greed and materialism surrounding us,” and while “doubt and concern trouble millions about our actions in Viet Nam,” King and the movement are “the great moral force in the country today.… You symbolize courage, effectiveness, singleness of will, honesty and idealism. You are free of the taint of political ambition, wealth, power or the pursuit of vanity. Your image has more purity than any American has attained in decades.” Several factors complicated the situation, Levison warned. One was the dynamics of the Selma protests: Nonviolent direct action was proven by Selma to have even greater power than anyone had fully realized - eBook - ePub

- John A. Kirk(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter 5 ___________________A Movement in Transition, 1965–6

King and the SCLC’s 1965 Selma campaign marked the culmination of its southern-based Birmingham strategy, which it had developed since 1963. Working alongside SNCC and local people, King and the SCLC ran nonviolent, direct-action demonstrations that led to confrontation and conflict with Alabama state troopers. The violence used against the demonstrations prompted federal intervention in the form of troops on the ground and federal legislation with the introduction of the voting rights bill to Congress, which was later passed as the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The Selma campaign brought more public sympathy, support from northern whites and action from the federal government than any other event in the civil rights movement.Yet Selma gave way to a period of transition that signalled the drawing to a close of one phase of the civil rights movement and the beginning of another. With two of the central demands of the movement met – the 1964 Civil Rights Act ending segregation in public facilities and accommodations, and the 1965 Voting Rights Act removing obstacles to black voting rights – King, the SCLC and others in the civil rights movement faced the question of what their future goals should be.As King and the SCLC reflected upon what to do next, it was developments elsewhere that shaped their response to that question. Just five days after President Johnson signed the 1965 Voting Rights Act, one of the worst race riots of the post-war era broke out in Watts, Los Angeles. There had been racial disturbances in several cities the year before and Watts presaged a number of riots that rocked urban areas, particularly in the west and north of the United States, over the following years. Partly as a result of the Watts riot, King and the SCLC launched their first northern-based campaign in Chicago, where they attempted to modify their Birmingham strategy to address the multitudinous problems of the northern black ghetto. While the Chicago campaign was under way, the slogan of ‘Black Power’ was popularised by new SNCC chair Stokely Carmichael on the James Meredith-inspired March Against Fear through Mississippi. The slogan quickly gained currency, particularly among militant black youth groups. The outbreak of urban rioting and the emergence of black power highlighted black constituencies that King and the SCLC, by hitherto concentrating on southern small towns and cities, had largely left ignored: the black urban poor and powerless in America’s major cities and the black rural poor and powerless in isolated southern communities. Both these groups felt increasingly neglected by the civil rights movement. Indeed, many of those people began openly to question if the goals and tactics of the civil rights movement as King and the SCLC articulated them were, in fact, relevant to them at all. - eBook - ePub

Running for Freedom

Civil Rights and Black Politics in America since 1941

- Steven F. Lawson(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

4 Reenfranchisement and Racial ConsciousnessThe Selma Movement and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The distance between Oslo, Norway, and Selma, Alabama, spanned more than an ocean and thousands of miles. For African Americans it represented the difference between dignity and degradation. The winner of the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., returned to the United States after obtaining his prestigious award in Oslo and journeyed to Selma in hope of eliminating the gap between the honorific treatment he had received abroad and the lack of respect blacks were accorded at home. Specifically, he sought to do something about the continuing denial of their right to vote. Throughout the former Confederate states, approximately 57 percent of eligible blacks remained off the suffrage rolls; in Alabama, the figure was a more shocking 77 percent; and in Dallas County, where Selma was the county seat, only 335 blacks out of a total population of 15,000 were registered. With this in mind, on January 2, 1965, Dr. King told an audience gathered at Selma's Brown Chapel AME Church what was at stake in the demonstrations the SCLC was about to launch. “When we get the right to vote,” he predicted, “we will send to the statehouse not men who will stand in the doorways of universities to keep Negroes out, but men who will uphold the cause of justice.”King's plans capped the 20-year struggle to reenfranchise black southerners. Since the outlawing of the white primary in 1944, civil rights groups and the national government had attempted to remove discriminatory barriers impeding black suffrage. Though a combination of litigation, legislation, and voter registration campaigns had yielded much progress, the majority of southern blacks still were disfranchised and were likely to stay so unless state and local officials lost their stranglehold on the enrollment process. Like most of the gains made during the civil rights era, the expansion of black ballots depended upon the power of the federal government in reinforcing the efforts of blacks at the local level, who were already fighting for first-class citizenship. - eBook - PDF

Hosea Williams

A Lifetime of Defiance and Protest

- Rolundus R. Rice(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- University of South Carolina Press(Publisher)

Selma and the Voting Rights Act 141 forward. It was Bloody Sunday and the Selma-to-Montgomery march that galvanized support in the judiciary, legislative, and executive branches of the federal government for a voting rights bill—landmark legislation that was signed by President Johnson on August 6, 1965. The Voting Rights Act made literacy tests illegal as a perquisite to vote, and it also authorized the US Attorney General to block state and local authorities from using the poll tax, the white voucher system and other subjective measures that were arbitrarily applied to aspiring Black voters. In spite of the promises of fair voting practices that had been codified by the new legislation, Hosea Wil-liams and the SCLC did not rest on their laurels. 41 The march from Selma to Montgomery was relatively free of any se-rious incidents of violence until Viola Liuzzo was murdered around 8:30 pm on March 25 while driving her Oldsmobile along Highway 80 in rural Lowndes County, approximately 26 miles east of Selma—coincidentally along the same route that marchers walked in an earlier trek of the jour-ney to Montgomery. Liuzzo, a thirty-nine-year-old mother of five children, and student at Wayne State University, had driven south from Detroit, Michigan, to participate in the march for voting rights after Bloody Sun-day in response to King’s nationwide call when she suffered from bul-let wounds to the temple and neck. Liuzzo had been accompanied by nineteen-year-old Leroy Moton, a Black barber, who was in the car when the two were returning to Montgomery after shuttling protesters in Selma. In less than seventeen hours, four Klansmen—Collie Leroy Wilkins Jr., Gary Thomas Rowe, William Orville Eaton, and Eugene Thomas—were arrested for the senseless murder. Rowe was an FBI informant who later testified that Wilkins was the shooter. - eBook - ePub

In Peace and Freedom

My Journey in Selma

- Bernard LaFayetteJr., Kathryn Lee Johnson, Bernard LaFayette Jr.(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- The University Press of Kentucky(Publisher)

We wouldn’t carry the body of Jimmie Lee, but we would carry the weight of the movement and the grief of his family, and all would be empowered. The long march would give people a chance to think about the issues, to join in, and to prolong the pilgrimage. We planned for the march from Selma to Montgomery to begin in about two weeks following Jimmie Lee’s death. We thought that people could walk ten miles a day, so it would take five days, which I considered perfect to prolong the pilgrimage. This direct action was designed to mobilize the nation and to have a major impact in highlighting the issue of voting rights. We knew that many people in Selma could walk only for a couple of days, so it was necessary to feed the march from the outside and increase the numbers for more impact. We appealed to people to come from all parts of the country. It no longer was a local protest, but became a national movement. Several leaders were sent to cities all over the country to bring marchers down to Selma. I returned to Chicago to attend some meetings necessary for my job, but also to recruit people from that community to come south to support the Selma march. I planned to join them on the second day.When the first march was planned, Dr. King couldn’t be there on Sunday, the first day, but it was decided that the march should begin anyway and he would join it later. Dr. King and his father copastored the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. They alternated preaching on the first Sunday of the month, the special Sunday when communion is celebrated. It was Dr. King’s turn, and he honored his commitment to his church. Rev. Ralph Abernathy, his movement colleague, was the pastor of West Hunter Baptist Church and also stayed in Atlanta to conduct his service. Rev. Abernathy was Dr. King’s closest friend; theirs was a lifelong friendship that began when they were both Baptist ministers in Montgomery during the 1955 bus boycott and cofounders of SCLC. He and Dr. King spent so much of their lives together, from planning campaigns, to being cellmates in jail, to being roommates in hotels, and their lives were so intertwined, that they were sometimes referred to as the “movement twins.” In private conversations Rev. Abernathy told me that he always thought their lives would end together. But fortunately, they didn’t. - eBook - PDF

It Was Like a Fever

Storytelling in Protest and Politics

- Francesca Polletta(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- University of Chicago Press(Publisher)

32 Commemorative Occasions Black legislative speakers did often forcefully describe a society marked by racial inequality and injustice. But the solution to such conditions was more storytelling. I noted earlier the speaker who asked, “If we stop and reflect on where we have gone since the marches and the sit-ins and boycotts of the 1960s, have we really gone far?” Her answer was to call for “daily efforts to correct the history that is taught to our children.” A speaker who emphasized that, despite the work of the civil rights move-ment, “conditions of homelessness, joblessness, teenage pregnancy, ab-sent fathers, high infant mortality, kids killing kids, and mental and physical illness abound” urged that “[we] constantly remind ourselves and others of the great contributions blacks have made and continue to make to this nation.” Senator Carol Moseley-Braun argued that it was “forgetfulness” about “the lessons [King’s] life taught us” that had “con-tributed to the widening gap that remains between the salaries of white and African American workers, the increasing gap between the incomes of middle and lower income African Americans, the continuing segrega-tion of our cities’ schools and communities, and the violence among our youth which has reached heights unimaginable even a few years ago.” If forgetting had such destructive consequences, then remem-bering should have equally transformative effects. In that vein, one speaker promised that legislation to commemorate the 1965 Selma to Montgomery March would teach future generations about “those early steps in the civil rights movement that began the road to making the Constitution of this country extend its rights and protections to all of its citizens. For some this will be freedom at last.” Another described CHAPTER SIX 160 movement commemorative activities in a project aimed at reducing teen-age pregnancy as essential to building self-esteem and responsible behavior. - eBook - PDF

A History of Hope

When Americans Have Dared to Dream of a Better Future

- NA NA(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

C HAPTER T EN T HE C IVIL R IGHTS M OVEMENT “I H AVE A D REAM ,” 1963 THIRTY YEARS AFTER A. PHILIP RANDOLPH first proposed a march on Washington, and one hundred years after Abraham Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation, on August 28, 1963, over 200,000 Americans marched in the nation’s capital and then stood in front of the Lincoln Memorial to hear the speeches. The keynote address of the March on Washington for Civil Rights was delivered by Martin Luther King Jr., already the nation’s most charis- matic and respected leader of the civil rights movement. In words that have be- come immortal, King declared his hope for America. “Go back to Mississippi; go back to Alabama; go back to South Carolina; go back to Georgia; go back to Louisiana; go back to the slums and ghettos of the northern cities,” King told the marchers, “knowing that somehow this situation can, and will be changed. . . . Let us not wallow in the valley of despair,” he said. Hope was coming. So I say to you, my friends, that even though we must face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed—we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal. King knew that the dream would need to become a reality in some of the na- tion’s most difficult places; in Mississippi, “a state sweltering with the heat of in- justice,” and in Alabama, “with its vicious racists.” Yet it was right there in places 250 A HISTORY OF HOPE like Mississippi and Alabama that King believed that, “little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” That was his hope and his dream. - (Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Trade Paper Press(Publisher)

The LDF also played a pivotal role during the Selma campaign as the legal arm of the movement that helped to secure the sanction of the courts for the courageous activists. During the marches LDF attorneys represented more than 3,400 protesters. LDF filed and successfully argued the federal court case challenging Governor Wallace’s executive order forbidding the marches, and it represented Dr. King in related legal proceedings. Protesters and civil rights strategists led the charge, and the LDF provided a necessary complement to their efforts in the courtroom.The efforts of activists, lawyers, clergy, performers, the young and old, southerners and northerners, were interwoven. Each was critical in fomenting change but change—in the form of the Voting Rights Act— came when it did because no one was left to stand alone. The Selma campaign was not simply a way to express outrage over unfairness, though it was certainly that. The right to vote was, and is, too central a component of full citizenship for the protesters and their supporters to tolerate fruitless protest. Selma dramatically showed the way in which outrage could be effectively channeled to bring about change, and the lessons learned in Selma remain relevant today.Is the Struggle for Full Voting Rights Unfinished?

Unabashed racial discrimination does not exist to the extent that it did a generation ago, nor where it continues does it always take the same form as in earlier years. For example, in 1965 as a result of racial discrimination only 1 percent of African Americans was registered to vote in Dallas County (which includes Selma, Alabama). Now, with African American voters comprising nearly 60 percent of those registered in Dallas County, the citizens have twice elected James Perkins Jr., who in 2000 became Selma’s first African American mayor. The achievement is even more meaningful because Mr. Perkins won his office by defeating former segregationist Joseph Smitherman, the ten-term mayor who was serving at the time of the Bloody Sunday attack. These positive changes are significant but realism and honesty require that we consider the ways in which yesterday’s discrimination has mutated in some cases or become more subtle in others.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.