History

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestant Christianity that traces its roots to the teachings of Martin Luther in the 16th century. It emphasizes the authority of the Bible, salvation by faith alone, and the priesthood of all believers. Lutheranism played a significant role in the Protestant Reformation and has had a lasting impact on the religious landscape of Europe and beyond.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Lutheranism"

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University Publications(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 1 Introduction to Lutheranism Lutheranism is a theological movement to reform Christianity with the teaching of justification by grace through faith alone. Lutheranism identifies with the theology confessed in the Augsburg Confession and the other writings compiled in the Book of Concord. Lutheranism is a major branch of Western Christianity that identifies with the theology of Martin Luther, a 16th century German reformer. Luther's efforts to reform the theology and practice of the church launched the Protestant Reformation. Beginning with the 95 Theses, Luther's writings disseminated internationally, spreading the ideas of the Reformation beyond the ability of governmental and churchly authorities to control it. The name Lutheran originated as a derogatory term used against Luther by Johann Eck during the Leipzig Debate in July 1519. Eck and other Roman Catholics followed the traditional practice of naming a heresy after its leader, thus labeling all who identified with the theology of Martin Luther as Lutherans. Martin Luther always disliked the term, preferring instead to describe the reform movement with the term Evangelical, which was derived from a word meaning Gospel. Lutherans themselves began to use the term in the middle of the 16th century in order to identify themselves from other groups, such as Philippists and Calvinists. In 1597, theologians in Wittenberg used the title Lutheran to describe the true church based upon the true doctrine of the gospel. The split between the Lutherans and the Roman Catholics began with the Edict of Worms in 1521, which officially excommunicated Luther and all of his followers. The divide centered over the doctrine of Justification. Lutheranism advocates a doctrine of justification by grace alone through faith alone because of Christ alone which went against the Roman view of faith formed by love, or faith and works. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- College Publishing House(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter 1 Introduction to Lutheranism Lutheranism is a theological movement to reform Christianity with the teaching of justification by grace through faith alone. Lutheranism identifies with the theology confessed in the Augsburg Confession and the other writings compiled in the Book of Concord. Lutheranism is a major branch of Western Christianity that identifies with the theology of Martin Luther, a 16th century German reformer. Luther's efforts to reform the theology and practice of the church launched the Protestant Reformation. Beginning with the 95 Theses, Luther's writings disseminated internationally, spreading the ideas of the Reformation beyond the ability of governmental and churchly authorities to control it. The name Lutheran originated as a derogatory term used against Luther by Johann Eck during the Leipzig Debate in July 1519. Eck and other Roman Catholics followed the traditional practice of naming a heresy after its leader, thus labeling all who identified with the theology of Martin Luther as Lutherans. Martin Luther always disliked the term, preferring instead to describe the reform movement with the term Evangelical, which was derived from a word meaning Gospel. Lutherans themselves began to use the term in the middle of the 16th century in order to identify themselves from other groups, such as Philippists and Calvinists. In 1597, theologians in Wittenberg used the title Lutheran to describe the true church based upon the true doctrine of the gospel. The split between the Lutherans and the Roman Catholics began with the Edict of Worms in 1521, which officially excommunicated Luther and all of his followers. The divide centered over the doctrine of Justification. Lutheranism advocates a doctrine of justification by grace alone through faith alone because of Christ alone which went against the Roman view of faith formed by love, or faith and works. - eBook - PDF

Christianity and History

Essays

- Elmore Harris Harbison(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

The general nature of each may perhaps be suggested by saying that the religious genius of Lutheran- ism was best exemplified in Luther's hymns, that of Angli- canism in Cranmer's Prayer Book, that of Calvinism in its founder's Institutes, and that of Anabaptism in the idea of a purely voluntary church of converted believers. The Lutheran's warm inner piety and sense of being in, but not of this world; the Anglican's good sense and modera- tion in all things; the Calvinist's zest for theology and THE PROTESTANT REFORMATION moral discipline; the Anabaptist's naive enthusiasm for the literal imitation of Christ—these are startlingly distinct spiritual colors in the spectrum of Protestant piety. It is well not to blur them. In the sixteenth century a great deal of the richness and diversity of medieval Christianity, its wide range of Christian thought and feeling, passed di- rectly into the Protestant movement, while the Roman Church closed its ranks at the Council of Trent (1545-1563) and became a far more monolithic type of Christianity than it had ever been before. Lutherans broke with Calvinists, both argued with Anglicans, and all three burned Ana- baptists because of differences on the proper answers to the four questions already mentioned. There was a real measure of agreement among Protes- tants, however, especially when seen from the perspective of contemporary Rome. The area of this agreement may be roughly indicated by two words: Bible and conscience. In all the four major forms of Protestantism, the Bible and the individual conscience came to occupy the central position in Christian faith and life in a way which was never true of medieval Roman Christianity. So it is pos- sible to insist that Protestants differed, and at the same time to insist that they had something in common: a re- newed sense of Scripture and a heightened sense of the meaning of Christian conscience. - eBook - PDF

- Robert D. Linder(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

In society, Luther established a new emphasis on marriage as primarily a means of companionship that modeled godly living. In economics, Luther was a conservative and sided with the agrarian elements in society against the growing power of the capitalists, somewhat ironic in light of his own father’s acquisitiveness and thirst for upward mobility. In education, on the other hand, he was a progressive as he embraced the historic Protestant drive for an educated clergy and laity in order that all could read the Bible for themselves. In so doing, Luther urged compulsory universal educa- tion for both girls and boys. Science also flourished under Lutheran auspices. Luther even became a film celebrity of sorts as the modern motion picture industry produced several quality Luther films, the latest of which in 2003 became something of a box office hit. 27 How- ever, even the best of these films could not capture the real Luther whom historian Geoffrey Elton described as often ‘‘furious, violent, foul-mouthed, passionately concerned.’’ 28 In the end, Luther’s greatest contribution to modern history was his challenge to the dominant authority of the Medieval Church of his day. As he did, he not only shattered the theological and cultural unity of Western Christendom but also opened the door to the fur- ther questioning of societal authority in the following centuries. This largely unintended challenge to established authority and its results is the main theme of the Lutheran Reformation. This challenge, in 31 Martin Luther and the Beginning of the Protestant Reformation turn, encouraged freedom and made the world a far more dangerous place in which to live. Things would never be the same again. More- over, ironically, in the long term this development also strengthened Christianity by emphasizing that true faith could only flow from freely made decisions to embrace and follow Jesus Christ. - eBook - PDF

- C. Scott Dixon(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Much of what the early Protestant authorities wanted to accomplish remained unfulfilled, many of the basic features of the religion had not taken root (Strauss, 1978, pp. 249–308; Vogler, 1981, pp. 158–96; Scribner, 1993b, pp. 221–41). No one realized this better than the Protestant clergy them-selves, in particular the Lutheran clergy, who withdrew deeper and deeper into a sense of pessimism, failure and impending doom as the century counted down. But perhaps the Protestant clergy were wrong, as we would be wrong, to judge the movement by the standards established by men of such systematic and inspired thought as Martin Luther, Huldyrich Zwingli and Jean Calvin. Perhaps the true legacy of the Reformation lies less in its faithfulness to an original vision than the complex, if unforeseen, change of per-spective it inspired. ‘Perhaps,’ writes Peter Matheson, ‘what happened in the Reformation was that one imaginative archi-tecture was replaced by another’ (Matheson, 2000, p. 7). For this much seems certain: once the Reformation movement had spread beyond the culture of the clergy and the schoolmen, it had the ability to inspire people to think differently about things, all things, from the world of the spirit to the matters of the mind to the constituents of earthly welfare. Few episodes in European history have embraced so many aspects of the human condition. 6 Reformation Histories In the sixteenth century, public understanding of the German Reformation was first expressed through figurations of Martin Luther. The reformer was portrayed in a number of symbolic guises, each of which served to explain and legitimize the move-ment. First and foremost was the notion of Luther as prophet, God’s chosen vessel sent to preach the Gospel and overthrow idolatry (by which the Protestants meant the papacy). Most of the leading reformers thought of Luther as God’s messenger on earth, and by mid-century this idea was rooted in the evangeli-cal histories of the day. - eBook - PDF

Western Civilization

A Brief History, Volume II: Since 1500

- Jackson Spielvogel(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

The agitation for certainty of salvation and spiritual peace was done within the framework of the “holy mother Church.” But disillu-sionment grew as the devout experienced the clergy’s inability to live up to their expectations. The deepening of religious life, especially in the second half of the fif-teenth century, found little echo among the worldly-wise clergy, and this environment helps explain the tre-mendous and immediate impact of Luther’s ideas. Martin Luther and the Reformation in Germany Q F OCUS Q UESTION : What were Martin Luther’s main disagreements with the Roman Catholic Church, and what political, economic, and social conditions help explain why the movement he began spread so quickly across Europe? The Protestant Reformation began with a typical medi-eval question: What must I do to be saved? Martin Luther, a deeply religious man, found an answer that did not fit within the traditional teachings of the late medieval church. Ultimately, he split with that church, destroying the religious unity of western Christendom. The Early Luther Martin Luther was born in Germany on November 10, 1483. His father wanted him to become a lawyer, so Luther enrolled at the University of Erfurt. In 1505, af-ter becoming a master in the liberal arts, the young man began to study law. But Luther was not content, due in large part to his long-standing religious inclina-tions. That summer, while returning to Erfurt after a brief visit home, he was caught in a ferocious thunder-storm and vowed that if he survived unscathed, he would become a monk. He then entered the monastic order of the Augustinian Hermits in Erfurt, much to his father’s disgust. In the monastery, Luther focused on his major concern, the assurance of salvation. The traditional beliefs and practices of the church seemed unable to relieve his obsession with this question. - eBook - PDF

Luther's Gospel

Reimagining the World

- Graham Tomlin(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- T&T Clark(Publisher)

PART A Luther and His Gospel 2 1 Luther and His Gospel During the last millennium, the world changed radically. Marco Polo and Christopher Columbus opened up new continents, William Shakespeare and Michelangelo produced some of the most sublime pieces of art, and Napoleon Bonaparte and Adolf Hitler changed the political face of their centuries. Yet a good argument can be made that one medieval monk outstripped them all in his-torical significance. Martin Luther and the Reformation he triggered have made a huge impact not just in Europe, but also in North America, Australia and the rest of the world. Around 800 million people worldwide belong to the various ‘Protestant’ denominations, none of which would exist without the events surrounding Luther’s pro-test against aspects of Catholic Christianity five hundred years ago. Protestantism has shaped a whole new way of life for people across the Western world and beyond, which has coloured their approaches to God, work, politics, leisure, family and, in fact, to almost every aspect of human life. It played a seminal role in the early development and continuing self-image of the United States, in the emergence of democracy and economic and religious free-doms in Europe, and was one of the key movements ushering in the changes from the medieval to the modern world. Luther can-not claim credit or blame for the whole of what eventually became Protestantism, but as one who played a critical role in the emer-gence of a new church and a new way of life for millions of people, the influence of his actions and beliefs on the past five hundred years has been incalculable. The modern world can barely be under-stood without them. LUTHER’S GOSPEL 4 4 Martin Luther was not the author, but became the accidental instigator of the Protestant Reformation through his famous pro-test about the abuse of Indulgences in 1517. - eBook - PDF

Postmodern Christianity

Doing Theology in the Contemporary World

- John W. Riggs(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Trinity Press International(Publisher)

As Protestantism moved from the last third of the sixteenth century into the seventeenth, and as the second generation of great Reformers died, classical Protestantism moved into the period of orthodox Protestantism. 25 When the Formula of Concord (1577) formalized the division between Luther-anism and the Reformed tradition, new challenges arose. The two traditions needed to be defined carefully, pastors needed to be trained in those traditions, and Protestantism needed to defend itself against Roman Catholicism. The task of formalizing the Reformation insights fell on the Lutheran side to men like Johann Gerhard (1582-1637), Abraham Calov (1612-1686), and Johann Andreas Quenstedt (1617-1688). For the Reformed tradition, the work was carried on by Theodore Beza (1519-1605), Amandus Polanus (1561-1610), Johannes Wolleb (1586-1629), Johann Heinrich Heidegger (1633-1698), François Turettini (1623-1687), and others. Although these two Reformation 23 POSTMODERN CHRISTIANITY trajectories carefully distinguished themselves one from the other, they shared certain features while other features were distinct. Protestant orthodox theologians produced multivolume systems of theol-ogy. These systems were arranged in carefully derived categories that covered all conceivable options within any given topic. The philosophy of Aristotle was often employed in making the many subtle distinctions that were made. While this may seem like a retreat from the Reformation back to the medieval captiva-tion of theology by philosophy, orthodox theologians insisted that Christian theology was only to be done by believers, with a focus on Christ and the reli-gious life that ensued. Luther's phrase comes to mind that one could turn to phi-losophy if first one were a fool for Christ. Protestant orthodoxy turned its systematic eye first toward Scripture, follow-ing the Protestant principle of Scripture alone (sola scriptura). - Virginia Garrard-Burnett, Paul Freston, Stephen C. Dove(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Immigrant Protestantism: The Lutheran Church in Latin America 309 A case study of Lutheran congregational and church life in Latin America is presented in the text that follows through the example of the Evangelical Church of the Lutheran Confession in Brazil. However, some overall char- acteristics of Lutheranism in this part of the world could be summarized at this point. Lutheranism did not come to the area in the wake of the sixteenth-century European expansion. To begin with, it had traits of isolated European colonies, as in the Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and Suriname, but Lutheranism also came as a diaconal ministry to these islands, siding with suf- fering African slaves. In contrast, Lutheranism as an immigrant church arrived in Brazil and Argentina as part of an official attempt to “whiten” countries with a high proportion of African slaves in their populations. The multiplicity of theological tendencies nowadays has given rise to some division within the churches. Some congregations have been heavily influenced by Pentecostal movements, in some cases leading to the practice of rebaptism of Catholic converts. On the other hand, there are remarkable signs of ecumenical coop- eration as well. Although Lutheran churches on the whole have maintained a strong ethnic profile, there has been a concerted effort to break through ethnic barriers, especially in larger cities. Lutheran churches have on the whole taken a strong stand on political and social issues. The main contributing factor in this sociopolitical awareness has been the independent theological reflection taking place throughout Latin America. The case study of Brazil will illustrate many of these region-wide features.- eBook - PDF

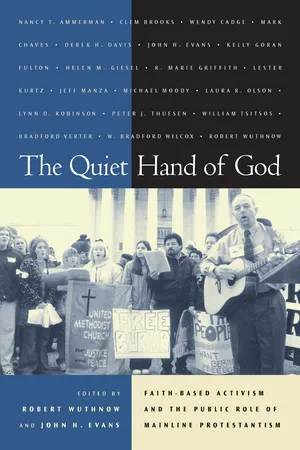

The Quiet Hand of God

Faith-Based Activism and the Public Role of Mainline Protestantism

- Robert Wuthnow, John H. Evans, Robert Wuthnow, John H. Evans(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

This logic, which resembles secular progressivism while also sharing a Catholic commitment to universality, evolved in the course of successive historical transformations, including the Reformation, the En-lightenment, the American Revolution, the American Civil War, and the 28 / Peter J. Thuesen advent of modern bureaucratic capitalism. In this chapter, I shall provide a broad historical overview of how these successive events contributed to the liberal institutional logic so familiar to the mainline churches’ sup-porters and critics today. the reformation background In sixteenth-century Europe, the modern notion of the church’s “public” role (as distinguished from its “private” spiritual functions) had little or no meaning. Ever since the time of Constantine, politics and religion had been virtually indistinguishable, and the leading sixteenth-century re-formers did not seek to destroy the Constantinian synthesis. In this re-spect, the Reformation was a premodern event. Significantly, the Refor-mation was also premodern in its readings of Scripture: the biblical narrative was generally assumed to be continuous with the drama of late-medieval daily life as one seamless web of truth. Religious skepticism, though present to some degree in all ages, lacked the modern scientific valences familiar in discourse today. In its practical effects, however, the Reformation began the irreversible transition to modernity. Three closely interrelated effects are particularly important for later American life. First, the Reformation led to an enduring Protestant suspicion of ecclesiastical authority. Although Luther, and in the next generation Calvin, retained an emphasis on the special functions of ministers, the reformers’ theologies provided new justification for the exercise of lay authority. Luther, in particular, spoke of the “priesthood of all believers” and rejected the notion that clergy belonged to a hierarchical caste with an indelible priestly character.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.