History

Temperance Movement

The Temperance Movement was a social and political campaign in the 19th and early 20th centuries that aimed to reduce or prohibit the consumption of alcohol. It was driven by concerns about the negative effects of alcohol on individuals and society, and it led to the establishment of organizations and laws promoting temperance and prohibition.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Temperance Movement"

- J. David Hoeveler(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- University of Wisconsin Press(Publisher)

110 6 Progressivism 1: Temperance T he movement to ban the manufacture, sale, and consumption of alcoholic beverages seems bizarre from the vantage of the twenty-first century, or from any time after 1919. It probably strikes most people today as an aspect of ir- rationality, of puritanical moralism, of misplaced idealism. Why would a whole nation vote to deny itself one of life’s simple pleasures? For a full century or so, however, temperance, and then the legislation to prohibit all traffic in intoxi- cating drink, shared center stage in American social movements and political party politics. The issue just wouldn’t go away, and ultimately it found its way into the United States Constitution. Significantly, the Temperance Movement had critical attachments to other aspects of American life—to religion and denominational differentiations, to ethnic cultures, to the party ideologies of Whigs and Democrats and then of Democrats and Republicans, and to the role and power of women in the larger society. The movement has given historians much to ponder. But temperance provided John Bascom a cause to which he remained committed all his life. 1 Alcoholic drink pervaded all aspects of American society in the early nineteenth century, de rigueur for nearly all events. 2 The situation began to 1. Joseph F. Kett, “Review Essay: Temperance and Intemperance as Historical Problems,” Journal of American History 67 (March 1981), 878–79. See also Joseph R. Gusfield, Symbolic Crusade: Status Politics and the American Temperance Movement (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1963). 2. W. J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 18–20. Progressivism 1: Temperance 111 moderate by the middle of the 1830s, a change owed greatly to a vigorous tem- perance movement, underway from the earlier century, and fortified by other changes in American life.- eBook - PDF

- S. Robinson, A. Kenyon(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

The earliest Temperance supporters were not opposed to drink- ing beer, with total abstinence only becoming part of their teachings by the mid-1800s. They preached moderation and a life away from the gin ‘epidemic’. The Anglican Church championed the Temperance Move- ment’s stance regarding moderation in alcohol consumption. However, as the Temperance Movement focused more on abstinence, the Anglicans backed away. Teetotalism began to become a dominant feature of the Temperance Movement, as it slowly progressed from the fringes of soci- ety into the mainstream. As it became more mainstream, leaders, such as Joseph Livesey, radicalized and politicized the movement to extin- guish alcohol from Britain and beyond. Lower-class men would ‘sign the pledge’ and be made to feel responsible for themselves and their families, 20 Ethics in the Alcohol Industry feeling they could become a respectable member of society. The middle classes also turned away from alcohol and began to drink the new import of the day: coffee. To aid the acceptance of teetotalism, activists of the Temperance Movement began to provide ‘temperance drinks’ in addition to coffee, such as fruit juices. Eventually, even Coca-Cola was introduced as a ‘temperance drink’ (Babor et al. 2003), replacing the alcohol content of the popular European cocawine with a non-alcoholic syrup. By the late 1830s, the Temperance Movement was becoming a major social phenomenon, reinforcing awareness of the addictive nature of alcohol and its effect on the nation’s health, both social and physical. Alcohol as an addictive substance or ‘disease of the will’ (Valverde 1998) was a new concept, and one that the Temperance Movement used in the very first ‘anti-drinking’ campaigns. Prior to this period, alcohol had been seen in terms of its financial utility for the state; that is, used to raise money from tax, fines for drunken behaviour or incorrectly used legislated weights and measures. - eBook - ePub

Alcohol and Moral Regulation

Public Attitudes, Spirited Measures and Victorian Hangovers

- Yeomans, Henry, Henry Yeomans(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Policy Press(Publisher)

TWOTemperance and teetotalism

Introduction

This book concerns the historical development of public attitudes and the regulation of alcohol. Within this broad remit, the last chapter noted the potential salience of the Victorian Temperance Movement to these issues and outlined the book’s specific intentions to explore this further. How did this social movement relate to public attitudes to alcohol and the governance of drinking in England and Wales? This chapter will investigate this question through an examination of public discourse on alcohol and legal sources before and during the period in which the Temperance Movement emerged. Somewhere in the region of 500 newspaper and periodical sources have been considered and, additionally, a number of other sources are used, from David Wilkie’s painting ‘The Village Holiday’ to A History of Teetotalism in Devonshire by the West Country temperance activist W. Hunt. These sources supplied a large quantity of evidence with which certain key issues are explored. What were the views of the first wave of temperance followers? Did these differ from 18th-century concerns about drinking? How did the Temperance Movement relate to the legal and ideological context of its period?The emergence of the British Temperance Movement could feasibly be explained, using either moral panic theory or the rational, objectivist model of alcohol policy, as a straightforward response to a liberal legal stimulus. The first British temperance groups were formed in the late 1820s, before spreading across the country in the 1830s. The advent of temperance societies, therefore, coincided with a period of licensing reform, most notably engendered by the Beer Act 1830. This was a liberalising piece of legislation, which enabled householders to sell beer without the permission of the local licensing justice. This Act, in addition to the gradual replacement of domestic brewing with large-scale commercial brewing,1 coincided with a surge in the numbers of premises nationwide selling beer and an accompanying increase in the number of arrests for drunkenness.2 - eBook - ePub

Drink

An Economic and Social Study

- Hermann Levy(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The Temperance Movement tries to achieve voluntarily, by mere moral suasion, what legislation would attempt by means of prohibition: once a person abstains from the consumption of drink of his own will the immediate effect is much the same as if prohibition had rendered alcohol unavailable. The Temperance Movement or any movement which leads to abstention through moral suasion is therefore more comprehensive in its scope and more complete in its effect on the individual than any legislation based on partial restriction only. Legislation restricts the individual’s freedom to drink and affects the whole population in this limited way: the only criterion for success in moral suasion is the abatement of drinking as a step towards the ultimate goal of total and general abstention.The distinction between voluntary abstention and legal restriction has never been very strictly recognised by historians of the Temperance Movements. No doubt the Temperance Movements have always had this double function in mind: to influence the individual by suasion and education on the one hand, and to support legislation restricting the consumption of drink on the other. The latter function became more distinct as the movements grew in numerical strength and public recognition, and began to make sustained attempts to influence international opinion and, through this, react on national legislation. But this connection does not alter the fact that the Temperance Movement is in the first instance based on persuading the individual to keep voluntarily away from drink. One can hardly agree therefore with those who range early anti-drink legislation within the scope of the Temperance Movements. This has been done, for instance, in the otherwise excellent article by D. W. McConnell in the American Encyclopædia of the Social Sciences (see vol. XIV, 1935). Though we will follow him and fellow historians a little in their analysis, we shall try to bear in mind the distinction between the trends towards voluntary abstention and legislative restriction.McConnell points out that ‘Temperance Movements are almost as old in the history of humanity as the use of intoxicating drinks . . . the Chinese assert that as early as the eleventh century B.C ., one of their emperors ordered all the vines in the kingdom to be uprooted’. Earlier, the laws of Hammurabi, whose reign in Babylon is estimated to have been around 2000 B.C ., contain very drastic regulations as to wine drinkers; one of them lays down that ‘if a priestess who has not remained in the sacred building shall open a wine shop, or enter a wine shop for drink, that woman shall be burned’.1 This seems therefore to indicate that legislators considered wine shops as something more or less immoral, or, at any rate, not compatible with the life of the religious orders, merely one indication of the close interrelation early in history of the drink problem with religious and moral ideals which has been described in great detail and with much care by E. C. Urwin.2 - eBook - ePub

Alcohol, Power and Public Health

A Comparative Study of Alcohol Policy

- Shane Butler, Karen Elmeland, Betsy Thom, James Nicholls(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

This differed from the alternative view, that alcohol was essentially a beneficial substance – albeit one which could produce an array of harms if misused. Apart from the more radical voluntary teetotallers, most temperance advocates also agreed that the role of the state was primarily to reduce the overall consumption of alcohol through supply-side interventions. Alcohol consumption had to be tackled at a population level because it presented a risk to all drinkers, even if only a proportion ended up falling down the slippery slope to outright destitution. In this regard, Victorian temperance displayed many of the characteristics of later social movements: a shared core perspective, but a diversity of opinion on the most effective policy approaches. As with many social movements the differences could be significant, indeed rancorous; however, the shared enemy of temperance – the drinks industry, or simply ‘The Trade’ as it was known – provided a unified figure against which all sides cohered. While temperance discourse was grounded in moral arguments over rights, responsibilities and social progress, it was also shaped by developments in medical thinking around alcohol use. The work of eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century medical writers had helped position alcohol as a substance that could create, in some users, a type of habituation that was both distinctive and amenable to quasi-medical interventions. In 1814, a Scottish naval surgeon called Thomas Trotter produced a book entitled An Essay Respecting the Effects Medical, Philosophical and Chemical on Drunkenness and its Effects on the Human Body (Trotter, 1988) - eBook - PDF

From Demon to Darling

A Legal History of Wine in America

- Richard Mendelson(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- University of California Press(Publisher)

Rather than tolerating—and even encouraging—the consumption of wine and beer, the American Temperance Society required its members to pledge total abstinence. 67 Those who did so wrote T (total) on their pledges and became known as teetotalers. 68 Temperance advocates prided themselves on the powerful and immediate impact of their movement. According to the temperance leader and author Ernest Cherrington, the 18405 witnessed the founding of more temper-ance organizations of a general and national character than [at] any other period in the history of the United States. 69 This was nowhere more evi-dent than in the working-class Washingtonian movement that swept the nation in the 18405. The Washingtonians focused on the rehabilitation of drunkards, a theme that a century later would motivate Alcoholics Anony-mous. Washingtonians were indifferent to religion and eschewed coercion. 70 At their revivals, reformed drinkers recounted real-life experiences of drunk-enness and degradation and attested to how abstinence could help restore financial solvency and respectability. Statistics reflect the remarkable efficacy of the movement: annual per capita consumption of absolute alcohol dropped from about 7.1 gallons in 1810 to 3.1 gallons in 1840. 71 THE RISE OF LEGAL COERCION: FROM LOCAL OPTION TO STATEWIDE P R O H I B I T I O N Demographic and social changes began to threaten the steady advance of the Temperance Movement. As Pegram notes, Between 1845 an d ^55, nearly three million immigrants, the vast majority from Ireland and Germany, ar-rived to start a new life in America. 72 These immigrants brought with them a foreign and more lenient view of alcohol consumption. Drinking beer, wine, and spirits was an experience to be celebrated, enjoyed, and shared both at home and in public. - eBook - ePub

- Edith S Gomberg(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The New Temperance Movement: Through the Looking-Glass Dwight B. Heath, PhDSUMMARY . A long-term rise in drinking by Americans slowed in the 1970s and then reversed; several interest-groups pressed for higher taxes on alcohol, server-liability, severe penalties for drunk-drivers, a higher purchase-age, and many other legislative and regulatory restrictions. Several similar changes are occurring in other countries. A quasi-scientific rationale for reducing alcohol consumption links quantity directly to a wide range of social and individual problems, although the correlation often varies, both crossculturally and over time in the U.S. The new Temperance Movement holds out the false promise of a quick and easy solution to drinking problems, and provides a socially acceptable outlet that allows people to blame alcohol and wrongdoers in a Neo-Victorian complacency.In any discussion about current controversies in the drug field, one of the most pervasive and visible ones has to do with increasing pressures to reduce the consumption of alcoholic beverages among all populations. Ironically, it is also a controversy that is perceived as such by few other than those who have taken a strong stand on one side or the other. Many of the principal spokespersons are academicians and other scientists whose writings often are scrupulously phrased in order to minimize controversy, and much that is written on the subject is interpreted as scientifically based and, therefore, straightforward and objective. Besides which, who could be so hard-hearted as to take issue with the World Health Organization’s prescriptions for achieving “Health for all in the year 2000”? Unfortunately, much of what is said along these lines constitutes what many refer to as “the new Temperance Movement,” and it has more to do with politics and emotion than it does with science. - eBook - ePub

- Julie Robert(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

In reality, temperance organizations advocated for a range of state controls, such as licensing and limits on trading hours, to various forms of moral regulation (Yeomans 2011) centring on promoting overall moderation and/or banning the consumption of certain types of alcohol, namely spirits (Roberts 1982; Sulkunen 1990). Their positioning relative to commercial and consumer interests was also far from uniform, with only the more extreme elements of the movement centred on wanting to eliminate or diminish the sectors of the economy that derived profit from the production and sale of alcohol. Virginia Berridge encapsulates these beliefs with a disclaimer that prefaces her report on the potential lessons of temperance for twenty-first-century policymakers: ‘most people associate it with outdated attitudes, rigid moralism, narrow religion and an uncompromising attitude towards the consumption of drink’ (Berridge 2005: 1). Anti-temperance attitudes, epitomized in Australia by the maligned figure of the wowser (Room 2010) and the American post-prohibition backlash (Travis 2009: 61), are thus never far from TSIs and are guarded against in the public image these campaigns cultivate. The apprehension about unflattering associations notwithstanding, TSIs have largely taken these earlier Temperance Movements as normative examples. They have capitalized on many of their legacies, including their international philanthropic networks, their mustering of both medical and economic arguments, the utility of public commitments and even some of their lesser-known forms of involvement (such as time-delimited initial commitments) to create popular campaigns - eBook - PDF

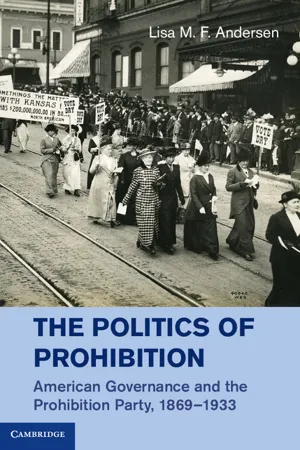

The Politics of Prohibition

American Governance and the Prohibition Party, 1869–1933

- Lisa M. F. Andersen(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

part i BUILDING A CONSTITUENCY 1 Temperance, Prohibition, and a Party Drinking liquor was the antebellum status quo, a practice so pervasive that there was little need to defend it. Taverns served as community centers, surplus rye and apples would rot if not distilled or fermented, and besides, Americans enjoyed imbibing. However, from the 1810s onward there flourished a growing Temperance Movement – that is, a movement encouraging people to limit the quantity and type of liquor they consumed. This movement nagged that the nation’s alcohol con- sumption levels had crossed the threshold of acceptability. Newspapers highlighted incidents wherein drinkers beat their spouses and children, had fatal accidents at work, fell into poverty, and committed crimes. Gos- sip and fiction gave special emphasis to the specter of urban overindul- gence. Tapping into widespread anxiety about the nation’s developing market economy, temperance advocates imagined the fates of young migrant workers who drifted away from the surveillance of families, ministers, and neighbors. Lonely and lost in cities, how many youths would find the comforting lure of drink too tempting to resist? At the same time, some of the ambitious farmers and manufacturers who embraced the market economy’s promise came to support temperance as an expression of their faith in self-improvement. 1 More and more 1 On the early Temperance Movement and its connection to a growing market economy, see Joseph R. Gusfield, Symbolic Crusade: Status Politics and the American Temperance Movement (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1963); Norman H. Clark, Deliver Us From Evil: An Interpretation of American Prohibition (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1976; William J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979); Ian Tyrrell, Sobering Up: From Temperance to Prohibition in Antebellum America, 1800–1860 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1979). 9 - eBook - PDF

- Nancy F. Cott(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Saur(Publisher)

Recent historical research lends strong support to these claims; W.J. Rorabaugh has estimated that the annual adult per capita consumption of absolute alcohol declined by a startling 75% in fifteen years of national temperance activity, from 7.1 gallons in 1830 to 1.8 gallons in 1845. 14 One of the most crucial aspects of the incipient victory, particularly for female temperance activists, was that it promised to secure a social environment within which children could be imbued successfully with strict teetotal principles. An Indiana temperance leader commented in 1845: Ask the most violent opposer to temperance if he is willing to go back & witness the scenes of 20 years past & prefer to raise his sons with the men of the habits of that day or the present? 15 The Temperance Movement, claimed The Pearl in 1846, had created in the young mind of this nation a higher and purer idea of what is right, just and true; and to a great extent, made these principles fashionable and popular, 16 Temperance progress, however, suddenly began to seem less certain in the late 1840s. Temperance reformers were soon convinced, in fact, that the tide had turned and that, in the words of The Peart, drunkenness is again in the ascendant. 17 Susan B. Anthony wrote to her mother in 1849 that the retrograde march of the temperance cause is truly alarming. 18 The principal causes of this changed perception were the massive influx of German and Irish immigrants during those years and the concurrent rise in urban social disorder. Temperance activists argued that only legal suppression of the drink trade could counteract the enslaving nature of alcohol addiction, the growing influence of the cabalistic Rum Power, the relative inaccessibility of the new immigrants to moral suasion appeals, and the fearful increases in poverty and crime. - eBook - PDF

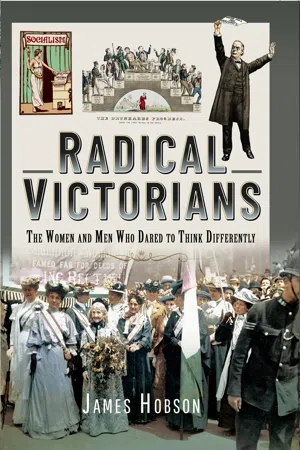

Radical Victorians

The Women and Men who Dared to Think Differently

- James Hobson(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Pen and Sword History(Publisher)

34 Chapter Three Temperance and Teetotalism Ann Jane Carlile The arguments against alcohol are as old as alcohol itself and were far from novel in the Victorian age. In summary, alcohol is a poison and its use was against reason. It endangered the drinker, their health and wealth and that of his family, his earthly reputation and his immortal soul. So it was a surprise that anybody touched the stuff – but they did, of course. The Victorian Temperance Movement is forever associated, some would say tainted, with its link to the religious revival of the Victorian period. It’s not easy to actively like the Victorian campaigner against drink, unlike some of our Victorian radicals. Hidebound by religious enthusiasm and moralistic finger-wagging, they seem to have been waging war on one of life’s pleasures. They talked down to people in the slums while drinking expensive wine in their own comfortable homes, and restricted their moral condemnation to the working classes. In short, they were killjoys, hypocrites and authoritarians. Some of these accusations were true, but perhaps not true enough to condemn them out of hand. The obvious counter to the first is that there was little joy to kill when it came to British drinking habits. If the drinkers of our age went back to 1800, they would have no doubt that drinking was a social problem with terrible consequences for the poor. Drunkenness was hard-baked into society, almost a right of freeborn Englishmen, alongside rioting and cruelty to animals. Eighteenth century governments were unwilling to legislate against personal vices unless social order was threatened. It was also a great revenue earner, one that the state could not, and did not want to, live without. When the House of Commons abolished the temporary Income Tax that was designed to finance the Napoleonic War (1816), they relied even more on the Malt Tax to plug the gap. Temperance and Teetotalism 35 By the 1820s, the tide was turning.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.