History

Women's Temperance Movement

The Women's Temperance Movement was a social and political campaign in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, primarily in the United States and Canada, advocating for the prohibition of alcohol. Led by women, the movement sought to address the negative social and economic effects of alcohol abuse on families and society, and it played a significant role in the eventual passage of Prohibition laws.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Women's Temperance Movement"

- eBook - PDF

- Nancy F. Cott(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Saur(Publisher)

Female participation in temperance agitation in the decades prior to 1873 was 72 HISTORY OF WOMEN IN THE UNITED STATES not static and monolithic, nor did it evolve gradually and evenly. Rather, a period of turbulent transition at mid-century sharply divides the history of women's temperance activism in this period into two distinct phases. Prior to 1850, women had been willing to remain subordinate to men in the areas of public activity and organizational leadership within the temperance movement because the reform efforts they carried out in their homes, within their domestic roles as mothers, wives, and sisters, were considered by all to be vital to the success of moral suasion. When in the 1850s temperance tactics shifted from the advocacy of moral suasion to that of prohibition, women were left without a meaningful function to perform in the movement, and they quickly began to demand an equal role in traditionally male spheres of action. Their efforts to gain full participation brought to many temperance women a new feminist perspective, causing them to swell the ranks of the emerging women's rights movement. Although women did secure an expanded role within the temperance movement, their inability to vote still left them largely powerless in the political arena. At the same time, temperance women began to fear for the safety of their own families. The acceptability of drinking among members of the native born Protestant middle class had declined steadily since the 1830s so that by mid-century, middle-class imbibing was rare and intoxication quite scandalous. During the 1850s, however, temperance reform experienced a reversal of fortunes, and drinking seemed to regain some of the popularity and respectability it had previously lost, while the drink trade itself gained in economic and political power. Women saw this change as immensely threatening to the security of their families. - eBook - PDF

Church and State in America: A Bibliographical Guide

The Civil War to the Present Day

- Bloomsbury Publishing(Author)

- 1987(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Yet until the late 1960s, scholars largely dismissed nineteenth-century temperance activists, both men and women, as an unbalanced group pursuing trivial, idiosyncratic ends outside the scope of the true reform tradition. The historiography of the 1960s sought to revise this interpretation by placing temperance within the social control model popular at the time, as best represented in Joseph R. Gusfield's thesis that the temperance movement was a bid for cultural dominance, a means for groups representing an older order to impose their own values on the diversifying nineteenth-century society and so retain their status in the American social hierarchy. With the discrediting of the social control model has come the beginning of a fuller understanding of the temperance movement. Recent work has recog- nized the genuine humanitarian concerns of many temperance activists, and also the worth of the movement itself. Alcoholism was common and destruc- tive, especially among the poor: nineteenth-century reformers saw clearly the continuing cycle of drink and poverty to which many working-class families were condemned. Women, economically dependent and without legal stand- ing, had a particular stake in this tragedy. A husband's alcoholism could destroy the family's security, their home, and sometimes their very lives. Once again, women entered the reform arena through domesticity, using their role as the custodians of family welfare to mount an assault on the drinking habits of the American male. Ian R. Tyrrell's article gives a good account of women's part in the movement in the years before the Civil War, and of the way in which "women reformers began to depict the drink prob- lem as a glaring and critical example of the sexual subordination of women" (p. 140). As in the social purity movement, women began to cast the con- sumption of alcohol in terms of sexual antagonism, and behind the condem- nation of drink lay a critique of the whole structure of gender relations. - J. David Hoeveler(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- University of Wisconsin Press(Publisher)

110 6 Progressivism 1: Temperance T he movement to ban the manufacture, sale, and consumption of alcoholic beverages seems bizarre from the vantage of the twenty-first century, or from any time after 1919. It probably strikes most people today as an aspect of ir- rationality, of puritanical moralism, of misplaced idealism. Why would a whole nation vote to deny itself one of life’s simple pleasures? For a full century or so, however, temperance, and then the legislation to prohibit all traffic in intoxi- cating drink, shared center stage in American social movements and political party politics. The issue just wouldn’t go away, and ultimately it found its way into the United States Constitution. Significantly, the temperance movement had critical attachments to other aspects of American life—to religion and denominational differentiations, to ethnic cultures, to the party ideologies of Whigs and Democrats and then of Democrats and Republicans, and to the role and power of women in the larger society. The movement has given historians much to ponder. But temperance provided John Bascom a cause to which he remained committed all his life. 1 Alcoholic drink pervaded all aspects of American society in the early nineteenth century, de rigueur for nearly all events. 2 The situation began to 1. Joseph F. Kett, “Review Essay: Temperance and Intemperance as Historical Problems,” Journal of American History 67 (March 1981), 878–79. See also Joseph R. Gusfield, Symbolic Crusade: Status Politics and the American Temperance Movement (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1963). 2. W. J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 18–20. Progressivism 1: Temperance 111 moderate by the middle of the 1830s, a change owed greatly to a vigorous tem- perance movement, underway from the earlier century, and fortified by other changes in American life.- eBook - ePub

- Cheris Kramarae, Ann Russo, Cherise Kramarae, Ann Russo, Cherise Kramarae(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Women had been active in the temperance movement since the 1830s in large numbers, and the temperance reformers looked to women as central participants in reform within the home; because the devastating effects of intemperance could most clearly be seen on women and their children, many women could identify with the need for change. The centrality of women to temperance reform, however, did not translate into women’s power to help direct and lead the movement; women activists continually came face to face with women’s powerlessness. Woman’s rights activism emanated naturally from women’s participation in the temperance movement, both in terms of the particular impact of intemperance on women’s lives and women’s lack of power to equally participate in temperance reform or in public policy (see “Work First for Power, Then Temperance”).As women spoke out on the connections between intemperance and male power, much controversy arose among women and men over priorities – some arguing that temperance was most important (see “Woman’s Rights Taints Temperance Movement”), some abolition, some woman’s rights, some dress reform, and some reformers argued that all issues need to be considered (see “All Victims of Tyranny Important”; also Dubois, 1978; Terborg-Penn, 1978; Allen and Allen, 1975; Davis, 1981). Women faced the particular problem of dealing with so-called progressive men who characterized woman’s rights advocates as unsexed, masculine and infidel women, characterizations used to control and inhibit women’s solidarity and interest in women’s issues.An interesting argument over priorities occurs in The Una between two white women. One writer argues that white women of the North should focus on home issues, rather than go to some other area of the country to fight against someone else’s oppression; the other disagrees and argues that white women should not abandon their Black sisters (“Fight White Slavery First” and “White Women Must Not forget Black Sisters”). Similar arguments took place over the importance of suffrage, labor and dress reform. We include here selections from the ongoing controversy regarding the position of the Woman’s Advocate - eBook - ePub

- Mari Jo Buhle(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- University of Illinois Press(Publisher)

While an awareness of changing labor patterns and familial roles inspired urban activists to urge woman’s advancement into civil society and to insist upon her right to meaningful labor, a growing dissatisfaction felt intensely in rural and small-town America called legions of women to attention. Industrial and urban growth might offer women either new opportunities or hardships, and activists sought to meet both contingencies. But the relative decline of the countryside in economic power and political prestige seemingly threatened to plunge the republic into chaos and to eclipse the progress of their sex at the very center of American civilization. Following the Panic of 1873, which fell heavily on small towns and rural areas, women found their own distinctive form of mobilization—the temperance crusade.For thousands of women temperance as a fighting slogan gave coherence to long-standing grievances. By lashing out at symbols of men’s abuse of power such as public drunkenness and political corruption stemming from the saloons, women helped to create a climate for a massive protest movement in the western states. Small-town and rural women also delineated a social critique and prescription for reform congruent with that of their urban sisters: to free themselves and to save the nation, women required the power only economic and political equality could bestow; to attain that power, women required a far-reaching sisterhood capable of overcoming all obstacles. Here especially the call for woman suffrage gained a new constituency and a new purpose. Not for abstractions alone did rural women demand the ballot but in order to bring womanly authority to bear upon a wicked world.The western woman’s movement grew from an outbreak of temperance evangelism beginning in the late 1860s and escalating significantly during the hard winter of 1873 and 1874. Through songs, prayers, scripture readings, and mass assemblies, women closed saloons in town after town across the Midwest. Within a year temperance agitation had spread so quickly, the pace of women’s activities so dramatically, that the cause became known as the woman’s revolution. In November, 1874, over 200 women representing organizations in seventeen states met to form the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.20Much like the urban activists, the most prescient leaders of the WCTU addressed from their first moment of involvement questions of women’s social and political status. Because they perceived the saloon as a direct challenge to the sanctity of women’s domain, the home, they reasoned that women must be enabled to protect their sacred trust by participating freely in civic life. Thus a resolution passed at the first WCTU convention stated boldly that “much of the evil by which this country is cursed comes from the fact that men in power whose duty is to make and administer the laws” had failed.21 Among the ranks the seeds of protest had already fallen upon fertile ground. As one self-styled “Private Dalzell” of the temperance army announced in 1874, “the seal of silence is removed from Woman’s lips by this crusade, and can never be replaced.”22 - eBook - ePub

Alcohol, Power and Public Health

A Comparative Study of Alcohol Policy

- Shane Butler, Karen Elmeland, Betsy Thom, James Nicholls(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Medical models of harmful drinking in this period were not homogenous, and the varying diagnoses produced a diversity of proposals for treatment. For ‘moral suasionist’ campaigners, the best method for reform was voluntary total abstinence, signified by adherence to a signed ‘pledge’ and, in many cases, public pronouncements of reform, and reinforced through active engagement with local total abstinence societies. For prohibitionists, the dependence-forming nature of alcohol required it being removed at source through radical state action. Within the medical temperance movement, however, other proposals emerged. In 1858, the Scottish physician Alexander Peddie published proposals for the establishment of ‘inebriate asylums’, based on the core principle that habitual drinkers were victims of a disease, and so required treatment rather than (as was often the case when their drinking led to criminality) punishment by law (Peddie, 1858). Peddie’s idea was taken up in America, where the first inebriate asylum was established in 1864, and such institutions were introduced to the UK following an Act of Parliament in 1879. The 1879 Act allowed for the establishment of voluntary asylums, which proved to be of limited value since they were both costly and required individuals to enter voluntarily. In 1898, state asylums were established that allowed courts to commit convicted criminals who, in the court’s view, were also habitual drinkers or who had been convicted of four alcohol-related offences. As subsequent historians have shown, the state asylums in reality were used primarily to commit women accused of prostitution or child neglect; furthermore, their value was never widely accepted and they fell largely into disuse after the First World War (Zedner, 1991; Valverde, 1998).Temperance was a diverse and varied social movement. It incorporated moral reformers, political activists from both the left and right (there were conservative, progressive and radical wings within the British temperance movement), doctors, social reformers, clergy from all denominations, and many thousands of ordinary men, women and – especially following the establishment of the Band of Hope in 1847 – children (see Harrison, 1971; Greenaway, 2003; Shiman, 1988; and Nicholls, 2009, for an overview). In all its guises, temperance drove a shift in the way the British government saw its relationship to alcohol and the drinks industry. Temperance activism forced policymakers to ask whether the primary role of policy was merely to ensure the market operated fairly (or, more sceptically, to support powerful industrial interests), or whether it was to proactively seek to reduce alcohol-related harms through supply-side controls. In this respect, the Victorian temperance movement presents clear antecedents to more recent public health advocacy on alcohol policy. For all its diversity, it was Victorian temperance that first established the notion that the state had a responsibility to seek actively to reduce harms, via a reduction in overall consumption, through supply-side controls on alcohol across the board. Furthermore, Victorian temperance first established the argument that the alcohol industry should have no hand in policy development, since its interests were – at the most fundamental level – antithetical to the reduction of alcohol harms. - eBook - ePub

- Julie Robert(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Bloomsbury Academic(Publisher)

The apprehension about unflattering associations notwithstanding, TSIs have largely taken these earlier temperance movements as normative examples. They have capitalized on many of their legacies, including their international philanthropic networks, their mustering of both medical and economic arguments, the utility of public commitments and even some of their lesser-known forms of involvement (such as time-delimited initial commitments) to create popular campaigns. The origins, rationales, forms, discourses and even exemplifying practices of temperance have nonetheless been reimagined and made palatable to contemporary audiences in a way that ‘temperance’ as popularly understood could not be.Temperate values on display

Temperance, as Gusfield (1986) established, is often framed as a response, admittedly a symbolic one, to a ‘moral panic’ (Cohen 2002) about alcohol consumption. This is to say that temperance was a reaction to the popular perception that alcohol was a problem that was worsening and that would continue to worsen without intervention. Analyses of both temperance and neo-temperance contexts reveal that in objective terms, alcohol consumption prior to the initiation of renewed calls for regulation and prohibition was in decline (Hunt 1999; Reinarman 1988). Images of alcoholic excess and sensationalist headlines – whether the gin drinking of nineteenth-century working-class England or the binge drinking of young women and ‘alcohol-fuelled violence’ that began to claim the attention of modern news outlets in Britain in 2004 (Berridge 2013) and Australia in 2008 (Azar et al. 2013) – nonetheless presented alcohol as an emergent threat to social order rather than as practices whose effects were mostly felt by individuals, most often individuals who were virtually unknown to the advocates of temperance. The order in question, albeit in different ways, relied upon self-governance as a means of distinction and differentiation. Temperance activities (both old and new), as Levine (1978) influentially argued, were accordingly predicated on the overt manifestation of restraint and responsibility as the symbolic solution to the perceived problem of rampant alcohol consumption. - eBook - PDF

Dry Manhattan

Prohibition in New York City

- Michael A. Lerner, Michael A. LERNER(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

7 I Represent the Women of America! A s the rebellion against the Eighteenth Amendment raged on in the 1920s, women would come to play a pivotal and surprising role in the demise of the noble experiment. That role was rooted in the transformation of the relationship between women and the American temperance crusade, as women moved from the traditional role of moral guardians and reformers in service to the dry lobby to rebels against the double standards of Victo-rian morality. In the end, women would become pioneering political lead-ers in the movement to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment. By the end of the Prohibition era, these women, roused by a broader campaign for women’s rights in the 1910s and 1920s, and caught up in the anti-Volstead culture of the Jazz Age, would completely redefine themselves and their re-lationship to the dry cause. In 1920s New York, the emergence of Jazz Age speakeasy culture thrust women into uncharted terrain. As the nation entered the dry era, the pre-vailing assumption, rooted in the public lore surrounding characters like Carry Nation or in the well-known activism of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, was that women had always been, and would always be, devotees of the dry cause. But for women in cities like New York, this ex-pectation became increasingly unrealistic as the Jazz Age took root. Once 171 welcomed into the world of the speakeasy, women in New York embraced the new culture, shattering the idea that women and the dry movement shared an unbreakable bond. From the outset of the Prohibition experiment, drys who had expected women to set a moral example for the rest of the nation were profoundly disappointed with what they found in New York City. The drys’ expecta-tions for women, naive as they were, were based on middle-class notions of morality and “respectability” that were particularly out of touch with the women who lived and worked in the ethnic, working-class communities of the city. - eBook - ePub

- Kenneth D Rose, Kenneth D. Rose(Authors)

- 1995(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

28The first rumblings of a female impatience with male progress on the temperance issue were interrupted by the Civil War, but the issues raised by women like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton returned with startling force in the Woman’s Crusade in 1873 and in the formation of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union a year later.29 The Woman’s Crusade was the first mass women’s movement in the United States, and it sent a clear signal that many women were now seeing temperance as a “gender” issue. The Crusade began when thousands of Ohio women took to the streets to pray in front of saloons and other liquor outlets because these women believed that by doing so they could eliminate the presence of liquor in their communities. They were at least temporarily successful. Thousands of saloons closed under this extralegal pressure, and the movement spread to the rest of the country, claiming the energies of an untold number of women who had formed the opinion that liquor, and liquor’s most public symbol, the saloon, was a threat to their communities.30Yet was this the case? Americans in the 1870s were actually consuming less alcohol than at any time in their history and had begun to shift their allegiances from distilled liquor to the more healthful beer. To a remarkable degree the American temperance movement of the antebellum period had succeeded in what it had set out to do: to reduce radically Americans’ consumption of alcohol.31 - eBook - PDF

Radical Victorians

The Women and Men who Dared to Think Differently

- James Hobson(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Pen and Sword History(Publisher)

When her biography was written in 1897, the introduction pointed out that she had led the way in women’s engagement ‘by resisting the criticism of press and pulpit’. 6 Temperance campaigners were accused of authoritarianism. The authoritarian streak was also a limited accusation, even when it was true. When religious men and women went into wretched working class communities to preach abstinence and self-denial (the language was similar to that of controlling sexual activity), they were also being very brave and making a statement about the need to improve the conditions of the poor and a personal willingness to do something about it when they could have done nothing. The propaganda weapon of choice was the temperance meeting, and it was far more sophisticated than just preachy finger-wagging. It was a battle for hearts and minds; people had to continue to be sober once the lecture was over. So the key elements were the lecture, the redemptive story with witnesses, and then the signing of the pledge. At a meeting at the Birmingham Temperance Society in 1839, chaired by the chocolate entrepreneur John Cadbury, an agricultural labourer, John Mayou, told the standard ‘redemption’ story. He had been a drunk for fifteen years and: It had robbed him of every domestic comfort, and during his time had spent in the public house sufficient money to have rendered him independent of all labour. He had been four years teetotaller, and though he did not wish to boast of what it had done for him, yet he might with truth say, that it had enabled him to find his way to a place of worship regularly ever since, and to pay for a comfortable seat there; besides which, was at least hundred pounds better in pocket. Radical Victorians 40 Temperance was a rational decision – the money saved proved it. It was also Mayou’s way of becoming independent of the bosses, and he used his newly found economic power to buy a better seat in church. - eBook - PDF

The Politics of Prohibition

American Governance and the Prohibition Party, 1869–1933

- Lisa M. F. Andersen(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

It would bring energetic moral perfectionism into the world of party politics. ∗ ∗ ∗ The Civil War era that preceded the Prohibition Party’s founding might seem like a “passive interlude” in the temperance movement’s history. 6 This lull can largely be explained, however, by the fact that temper- ance advocates were not single-issue reformers, but rather had multiple loyalties. Typical temperance advocates identified themselves as Chris- tians – often Methodist and sometimes Presbyterian, Congregational- ist, or Baptist – who opposed prostitution, gambling, prizefighting, and 5 Gerrit Smith quoted in “Temperance: Meeting of the National Convention,” Chicago Tribune, 3 September 1869. The language of slavery and emancipation was used very frequently in dry discourse. On the gendered dimensions of this language, see Elaine Frantz Parsons, Manhood Lost: Fallen Drunkards and Redeeming Women in the Nineteenth- Century United States (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003). 6 Jack S. Blocker, Jr., American Temperance Movements: Cycles of Reform (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1988), 71; Pegram, Battling Demon Rum, 43–45. 12 The Politics of Prohibition Sabbath violations, among other public vices. 7 In California, demands for reforming the railroad industry sometimes moved to center stage. 8 Under the duress of war most reformers deemed their obligations to the Union paramount and the opportunities for advancing abolition to be the most promising; the same community leaders who might have organized temperance fraternities or run dry legislative campaigns were instead coordinating support services through the United States Sani- tary Commission or religious conferences. The temperance movement’s self-imposed low profile during wartime might be compared to that of a closely related cause: the women’s rights movement. Women’s rights advocates routinely restrained their activities by canceling conventions or withholding criticism of politicians during the Civil War. - eBook - ePub

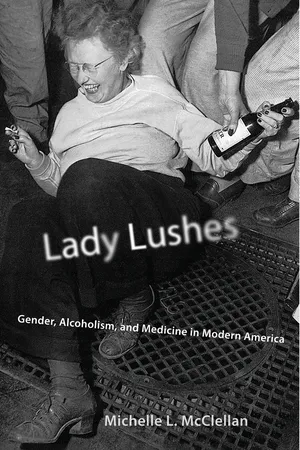

- Michelle L. McClellan(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Rutgers University Press(Publisher)

“Deplore it if you will,” one writer declared, “the number of men who drink is scarcely in excess of the number of women.” 106 Women’s involvement in the repeal campaign was also shocking to many. As one journalist declared in 1931, “What an upset of preconceived notions if it turned out to be the women of America and not the men who led in repealing the Eighteenth Amendment!” 107 Revealingly, however, even as the article went on to praise Pauline Sabin and celebrated women’s progress in “thinking for themselves” regarding Prohibition, no mention was made of women’s drinking. Similarly, while members of the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform did not “demur” when others described their drinking, they did not mention it themselves, and some wets, in fact, “expressed the same shock over women’s drinking as their dry opponents.” 108 Thus, while female solidarity regarding the liquor question no longer seemed a given, neither were women willing to assert a right to drink as a repeal tactic. Even as reports of women’s new drinking habits provided ammunition for Prohibition opponents, those who promoted repeal chose not to advertise their own consumption lest they lose respectability. As the delicate strategy used by repeal advocates suggests, American attitudes about women’s drinking remained uncertain as Prohibition ended. Had the new drinking customs been as widespread as some commentators claimed, they would have lost their power to shock. Still, the meanings assigned to women’s alcohol use had changed. The female inebriate who turned to alcoholic nostrums out of frailty and ill health now seemed as old-fashioned as temperance campaigners who could now be dismissed as stuffy and self-righteous. Women’s drinking came to look more like men’s, a form of recreational consumption to be engaged in for pleasure and enjoyment

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.