History

The New Nation of America

The New Nation of America refers to the period following the American Revolutionary War, when the United States emerged as an independent country. This era saw the drafting of the U.S. Constitution, the establishment of a federal government, and the development of a unique American identity. It was a time of nation-building and the laying of the foundation for the democratic republic that exists today.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

6 Key excerpts on "The New Nation of America"

- eBook - ePub

A Concise History Of American Painting And Sculpture

Revised Edition

- Matthew Baigell(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

2The New NationTHE YEARS covered in this chapter—the mid 1770s to the 1820s—encompass the birth of the United States of America, in 1781; the change in type of government after the acceptance of the Constitution in 1789; the development of those myths, customs, traditions, and even the language by which the inhabitants began to define themselves as Americans; and, not least, the experiment in republican self-rule.Artists, like probably everybody else, were participating in the initiation and growth of a new nation, and were constantly observing history in the making. People were self-conscious. How were artists to respond to these extraordinary times? What were their responsibilities and obligations? And, given the state of artistic training, support, and general understanding, what were their possibilities? As if these questions, each with endless ramifications, were not difficult enough, also other factors added complications. These included the development in human sensibility called Romanticism and the development of industrial society. In short, despite the explosive increase of the number of artists in America, it was not easy to be an American artist during these years.Some two hundred years later, it is not easy to make quick or abiding assessments. For example, several artists whom we consider major figures of the time—John Trumbull, Gilbert Stuart, John Vanderlyn, and Washington Allston—spent some of their most productive years abroad. Their training as well as the content of their art was, in great measure, foreign in inspiration. Conversely, several European-born and European-trained artists came to this country during this period and painted aspects of American life that appear closer to the ongoing concerns of the time than those depicted by the other group. And there were also Benjamin West and Copley, who settled in England permanently. In the years after the Revolutionary War, West and Copley were considered to be great American artists who proved to the world that the relatively uncultured provinces could produce artists equal to those of cosmopolitan centers. Yet, during a period of rising artistic nationalism in the 1830s, some of Copley’s English works—Watson and the Shark (1778)[33 ]and Death of the Earl of Chatham (1781)—were attacked for their pro-British biases (in William Dunlap’s History of the Rise and Progress of the Art of Design in the United States, - eBook - ePub

Jeffersonian America

How Jefferson and His Contemporaries Defined the Early American Republic

- Dustin Gish, Andrew Bibby, Dustin Gish, Andrew Bibby(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- University of Virginia Press(Publisher)

Part One Envisioning the New Nation P art one focuses on the republican character of the new nation and its place in history. Each essay weaves into its presentation rival visions articulated by Jefferson’s contemporaries on key problems confronting the new American republic. We open with the broader rhetorical problem of fashioning a unique self-understanding of the new nation in light of historical and ideological precedents from the past. The prospects for the new American republic also depended upon near-term success in formulating national diplomatic policy and generating a revolutionary form of republican politics that would begin to define the place of the United States of America within the existing framework of international powers. Rival Histories The Early American Republic’s Quarrel with Time Eran Shalev I n the summer of 1776, colonial British North Americans declared their independence from the empire and established a republic. This bold act caused numerous practical problems, which would be impressively dealt with, if only partly solved, a decade later with the ratification of a federal constitution. However, national independence also generated a lasting intellectual problem: the American union of states was a modern polity, but as such it was a nation that lacked firm historical precedence. Numerous citizens of the early United States rose to the challenge of rationalizing and justifying and placing their revolutionary political experiment in a historical context. They did so by elaborating compelling historical narratives, in light of which they attempted to describe and glorify their republic. The generation of founders thus presented themselves as the predecessors of free Anglo-Saxons and drew on classical polities, from Carthage to Athens and especially Rome. They lengthily compared themselves to the biblical Israelite federation and their leaders to Old Testament figures - eBook - ePub

The Story of Religion in America

An Introduction

- James P. Byrd, James Hudnut-Beumler(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Westminster John Knox Press(Publisher)

7. The New NationWhen determined colonists living on the edge of the frontier defeated the British Empire, their world changed. Many of them started believing that ordinary people had extraordinary potential. No longer did they need to tip their hats to social elites. They were as good as anybody. They had the chance to usher in a new era for a new nation, but what kind of nation would it be? Would it be ruled by a strong, centralized government, or would it be led by a loose confederation of states? And what role would religion play in the new nation?Whatever else happened, it was clear that American religion would be more diverse and more democratic than it had been in the colonial period. Democratic ideas inspired people, changed their outlook on life, and changed their religious views. In a nation that had no official religion, denominations competed with one another, turning religious life into a marketplace of ideas and practices, and it quickly became apparent that evangelicals had a decisive edge.1The Constitution and ReligionAfter the Revolutionary War had been won, colonists went about the business of founding a nation, and one of the most pressing issues was the need (or not) for a Constitution, a question that had not been decided by the time the Constitutional Convention was held in Philadelphia in 1787.Supporters of the Constitution, called “Federalists,” wanted a stronger federal government to revise the Articles of Confederation (1781), which had established a confederation of states that came together temporarily for common interests, like fighting wars, but left most of the power in the states.2 Although the Revolution had empowered more people to vote and even to hold public office, some wondered if this was a good idea. Would the common people be able to rule themselves? Or, more precisely, would the common people have the moral virtue and good sense necessary to elect able and virtuous leaders? By the 1780s some founders, including James Madison (1751–1836), had begun to worry. If average Americans lacked “virtue and intelligence to select men of virtue and wisdom,” then, Madison wrote, “no theoretical checks, no form of government, can render us secure.”3 - eBook - ePub

The Paradox of Citizenship in American Politics

Ideals and Reality

- Mehnaaz Momen(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

© The Author(s) 2018 Mehnaaz Momen The Paradox of Citizenship in American Politics https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61530-1_3Begin Abstract3. Nation-Building: Nation-States Versus Empire

End AbstractMehnaaz Momen 1(1) Social Sciences, Texas A&M International University, Laredo, Texas, USAAmericans came of age as citizens bathing in the glory of the Revolution, but within the short span of the eighteenth century, their self-identity as American citizens had to encounter a number of paradoxical features: the high ideals of equality, while maintaining exclusion for certain groups in society; encouraging political engagement and absolute liberty, while the power of the state invariably grew to check the limits of individual freedom; and superfluous economic and military power with a global reach, while retaining the preference for small government. All of these paradoxes clouded the notion of what American identity was, and produced mutually exclusive characteristics that seemingly were contained in the new and growing nation engaged in the quest for self-identification. The American Revolution transformed Americans from subjects to citizens, but it would take multiple wars, especially the Civil War , to uproot state identity and forcefully replant national identity as the cornerstone of citizenship. The events of the nineteenth century would further add to this confusion by expanding the nation, adding new groups of people, and introducing new processes of “othering,” some sanctioned by the state, some rooted in social norms. As discussed in Chap. 2 , in the early years of the republic, America was undergoing a transition from a monarchy to a republic, from disgruntled subjects to legitimate citizens. The story of the next chapter of the American nation throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is the story of expansion and empire-building. Wars and conflicts changed the shape of the country and altered the concepts of nationalism, identity, and citizenship. This chapter is about the domestic impact of American expansion, both in terms of territory and the power of the federal government, on American citizenship. The norms of citizenship were being rearticulated in the growing nation through wars, legislation, and both shrinking and expanding access points to practice citizenship rights. To uncover the evolution of citizenship as the state rose to unprecedented power, my focus is on the simultaneous expansion of the American state and the re-articulation of the rules of exclusion, along with the subtle theme of - eBook - ePub

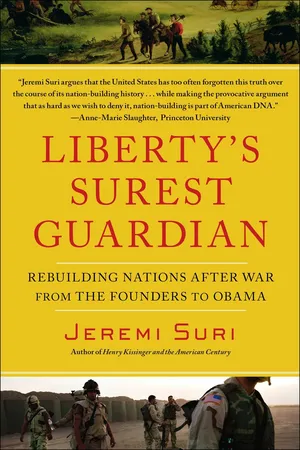

Liberty's Surest Guardian

American Nation-Building from the Founders to Obama

- Jeremi Suri(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Free Press(Publisher)

The creation of the American nation and government in the late eighteenth century unleashed an outpouring of participation on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean that forever changed the fabric of modern politics. “The Revolution,” one historian writes, “resembled the breaking of a dam, releasing thousands upon thousands of pent-up pressures. . . suddenly it was as if the whole traditional structure, enfeebled and brittle to begin with, broke apart, and people and their energies were set loose in an unprecedented outburst.” 17 The energies of citizens found collective voice in the constitutional institutions created to manage them. As “Americans,” literate individuals were now part of a national debate about a common government. “Public opinion”—measured in tone and attitude, rather than surveys or elections—shaped a national identity, government policies, and much more. The United States emerged as a new kind of broad and yet ordered democracy in action. “The Revolution,” Gordon Wood writes, “rapidly expanded this ‘public’ and democratized its opinion. Every conceivable form of printed matter—books, pamphlets, handbills, posters, broadsides, and especially newspapers—multiplied and were now written and read by many more ordinary people than ever before in history. . . . By the early nineteenth century this newly enlarged and democratized public opinion had become the ‘vital principle’ underlying American government, society, and culture.” 18 People felt they mattered as they had not before. Government now had to serve the people. Farmers and merchants, not kings and aristocrats, made the government. For these revolutionary circumstances to endure and prosper, nation and government had to remain closely tied together. The alternative was a reversion to separation and despotism. The alternative was a return of European empire on the ashes of the revolutionary experiment - eBook - ePub

America, War and Power

Defining the State, 1775-2005

- Lawrence Sondhaus, A. James Fuller(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1 Defining a New Empire

The New Power Takes Shape, 1775–1815

Jeremy BlackEditor’s introduction

Taking an outsider’s view, the author focuses on the context of international competition in which the United States formed. Challenging the traditional exceptionalist view, he argues that the first decades of the new republic were marked by war. To the degree that they helped to define the perspectives of the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, debates over military power were central to the politics of the early republic.America was a state born in war, and its early decades as an independent state involved the assertion of power through force, against both foreign and domestic challenges. Indeed, exigencies and debates focused on force, and how best to secure, sustain and use it, were crucial in the political and governmental history of these decades. This subject is generally neglected these days because of a preference, in accounts of the American Revolution and subsequent years, for social themes, especially topical ones of gender and race. Furthermore, among political historians, and, here again, there is no American exceptionalism, there has traditionally been a degree of reluctance in coming to terms with the formative context of international competition and military need. In seeking as a foreigner to discuss the subject, there is a danger that the opposite approach is taken, with an excessive focus on this context, at the expense, in particular, of the role of domestic political debate, in not only framing but also determining the understanding of this context, and therefore in providing the essential narrative. Yet, there is first-rate American work on the topic,1 and this chapter is intended as a contribution to be read alongside this literature.If contexts are the order at the outset, then the interpretative context also requires understanding. Here the key problem is posed by American exceptionalism, an approach that both discourages American scholars from looking for parallels that might add comparative insights, and foreign scholars from doing the same. The key context for this period is that, between 1776 and 1815, America was not alone in having to define itself as a new state in an acutely threatening international order, for this was also true of a host of states and would-be-states across the Western world; while all existing states, in responding to challenges, did likewise, albeit within far more established political patterns. The usual comparison for the American Revolution is with the French Revolution that began in 1789, but that, in fact, was only one among a number of European revolutionary or radical movements, and, in several countries in the 1780s, shortlived radical governments were established. These included Geneva, the United Provinces (modern Netherlands) and the Austrian Netherlands (modern Belgium), in all of which the new order was suppressed by counter-revolutionary force. The destruction of Polish independence early the following decade can also be located in this context, as the reform movement that had drawn up a new constitution in 1791 was a particular issue for Catherine the Great of Russia. Furthermore, as another comparative element, the range of territories affected by secessionist movements in the European colonial world also included Ireland (against British rule in 1798) and Haiti (against the French).

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.