History

The Space Race

The Space Race was a competition between the United States and the Soviet Union to achieve significant milestones in space exploration. It began in the late 1950s and culminated with the United States successfully landing astronauts on the moon in 1969. This period of intense rivalry and technological advancement had significant political, scientific, and cultural implications.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "The Space Race"

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University Publications(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 3 Space Race The Space Race was a mid-to-late twentieth century competition between the Soviet Union (USSR) and the United States (USA) for supremacy in outer space exploration. Between 1957 and 1975, Cold War rivalry between the two nations focused on attaining firsts in space exploration, which were seen as necessary for national security and symbolic of technological and ideological superiority. The Space Race involved pioneering efforts to launch artificial satellites, sub-orbital and orbital human spaceflight around the earth, and piloted voyages to the Moon. It effectively began with the Soviet launch of the Sputnik 1 artificial satellite on 4 October 1957, and concluded with the co-operative Apollo-Soyuz Test Project human spaceflight mission in July 1975. The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project came to symbolize détente, a partial easing of strained relations between the USSR and the USA. The Space Race had its origins in the missile-based arms race that occurred just after the end of the World War II, when both the Soviet Union and the United States captured advanced German rocket technology and personnel. The Space Race sparked unprecedented increases in spending on education and pure research, which accelerated scientific advancements and led to beneficial spin-off technologies. An unforeseen consequence was that The Space Race contributed to the birth of the environmental movement; the first color pictures taken from space were used as icons by the movement to show the Earth as a fragile blue planet surrounded by the blackness of space. Origins World War II The Space Race can trace its origins to Nazi Germany, beginning in the 1930s and continuing during World War II when Germany researched and built operational ballistic missiles. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- University Publications(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 10 Space Race The Space Race was a mid-to-late twentieth century competition between the Soviet Union (USSR) and the United States (USA) for supremacy in outer space exploration. Between 1957 and 1975, Cold War rivalry between the two nations focused on attaining firsts in space exploration, which were seen as necessary for national security and symbolic of technological and ideological superiority. The Space Race involved pioneer-ring efforts to launch artificial satellites, sub-orbital and orbital human spaceflight around the earth, and piloted voyages to the Moon. It effectively began with the Soviet launch of the Sputnik 1 artificial satellite on 4 October 1957, and concluded with the co-operative Apollo-Soyuz Test Project human spaceflight mission in July 1975. The Apollo-Soyuz Test Project came to symbolize détente, a partial easing of strained relations between the USSR and the USA. The Space Race had its origins in the missile-based arms race that occurred just after the end of the World War II, when both the Soviet Union and the United States captured advanced German rocket technology and personnel. The Space Race sparked unprecedented increases in spending on education and pure research, which accelerated scientific advancements and led to beneficial spin-off technologies. An unforeseen consequence was that The Space Race contributed to the birth of the environmental movement; the first color pictures taken from space were used as icons by the movement to show the Earth as a fragile blue planet surrounded by the blackness of space. Origins World War II The Space Race can trace its origins to Nazi Germany, beginning in the 1930s and continuing during World War II when Germany researched and built operational ballistic missiles. - eBook - PDF

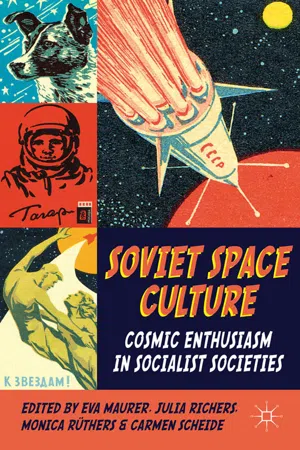

Soviet Space Culture

Cosmic Enthusiasm in Socialist Societies

- E. Maurer, J. Richers, M. Rüthers, C. Scheide, E. Maurer, J. Richers, M. Rüthers, C. Scheide(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

Outer space was considered to be another potential battlefield of the two superpowers and the race to the Moon was often seen as the defini- tive vanishing point of all endeavours in this ‘substitute war’ in space. 16 The growing neo-colonial desires of the superpowers had to be regu- lated by the international Outer Space Treaty of 1967. From then on, no nation could claim ownership of outer space, for example the Moon or other celestial bodies such as Mars. In addition to the construction of a realistic military threat scenario, the ‘astropolitics’ on both sides of the Iron Curtain were part of a competition between different world views and about intellectual, scientific and technological innovations. In most historical accounts, the starting point for the great space race of the superpowers was the launch of the first artificial satellite Sputnik in October 1957. 17 The beeping metal ball which flew over American living rooms once every hour not only led to the so-called ‘Sputnik shock’, in many ways it also indicated a fundamental turning point in military technology, espionage, media, communications and cultural history. 18 In view of the vast number of historical and popular science publi- cations on The Space Race during the Cold War, this chapter mentions only a small selection of reference works dealing with the Soviet side of The Space Race. The monograph by the American historian Walter A. McDougall titled The Heavens and the Earth. A Political History of the Space Age was published in 1985 and is still one of the most important introductions to the topic, despite the fact that the political rhetoric of the Cold War left some traces in his writing. 19 Another renowned work is William E. Burrows’ This New Ocean: The Story of the First Space Age - Ann Darrin, Beth L. O'Leary, Ann Darrin, Beth L. O'Leary(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

229 13 Space Race and the Cold War Richard Sturdevant and Greg Orndorff CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................ 230 Launch Vehicles ..................................................................................................... 230 Satellites ................................................................................................................. 232 Terrestrial Support to Launch and Space Systems ................................................. 240 Terrestrial Systems to Watch Launch and Space Systems ..................................... 242 Fighting in Space ................................................................................................... 244 Human Construct ................................................................................................... 247 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 248 Further Reading ..................................................................................................... 249 United States ................................................................................................ 249 USSR ............................................................................................................ 250 230 Handbook of Space Engineering, Archaeology, and Heritage INTRODUCTION From the late 1940s to the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, that country and the United States engaged in a Cold War, politically and militarily. In terms of both national prestige and military security, space became a competitive arena. This chapter outlines, in a categorical and technological sense, the predominant national-security aspects of that competition and their evolution over the course of the Cold War.- eBook - ePub

Sovereign Mars

Transforming Our Values through Space Settlement

- Jacob Haqq-Misra(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- University Press of Kansas(Publisher)

CHAPTER THREE

The Outer Space Treaty

Space exploration today prominently features cooperative missions by the world’s space agencies, with increasing involvement from commercial space agencies. Many small and developing nations have initiated their own space programs to gain satellite capabilities that support local telecommunication industries, which often depend on partnerships with states that already have launch capabilities. Increased access to education in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics has accelerated the growth of the space sector, while the development of small-form-factor satellites (known as “nanosatellites”) enables low-cost space-based experiments by space agencies or even teams of students. Such capabilities also increase participation by space agencies large and small in the international scientific community, which allow many contemporary and planned space missions to include representation from multiple states.The history of space exploration, however, is intimately connected with the Cold War arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union. The associated space race between these two states represented one of the ongoing struggles for technological dominance between democratic states in the West and communist states in the East. The intertwining of scientific progress and geopolitics during the Cold War played out in violent conflict on Earth, while public demonstrations of technology, such as the launch of the first human into space by the Soviet Union and the first crewed lunar landing by the United States, served to showcase each state’s missile launch capabilities. Cold War tensions have since eased as both states reduced their nuclear arsenals and other states gained nuclear capabilities, which has increased access to the launch technology required to conduct space activities. The entry of new state and commercial agencies into the space domain has further reduced the connection between military objectives and space exploration, but space remains an important strategic domain for state-sponsored espionage and defense. - eBook - PDF

- Deganit Paikowsky(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

4 A Multilateral Race for Space Club Membership The Cold War race to space is usually referred to as a bilateral competition. But in practice, a multilateral competition over space achievements took place, and it still takes place. The competitive atmo- sphere, propaganda, and public diplomacy of the two superpowers over space exploration created norms and conventions about the importance of space for national might and stressed the exclusivity of national space capability. Other states adopted the message and were, and still are, interested in catching up by demonstrating similar capabilities in order to win tangible economic and development goods and enjoy the added strategic, political, and social values attributed to space expertise. This chapter provides insights on the perceptions held by decision- makers and state officials of emerging spacefaring nations, as well as medium-sized and small states, concerning the politics of space and the values they attribute to achievements in this field. These weaker states accepted the interpretation offered by the superpowers that space pro- grams are means and symbols of power and used it for their own national and international purposes. Medium-sized and small states aspire to emulate the superpowers in deeds and in declarations by stressing the importance of developing a leading indigenous position. Their behavior resembles a techno-nationalist approach and so does their rhetoric when justifying and vindicating investments and national efforts to develop a national space capacity. They socially construct their achievements as an act of joining the space club, while stressing their self-reliance to distinguish themselves from lower-status states or creating proximity to higher-status or equal-footing states in order to achieve the lofty status and gains that are reserved for members only. - eBook - ePub

Militarizing Outer Space

Astroculture, Dystopia and the Cold War

- Alexander C.T. Geppert, Daniel Brandau, Tilmann Siebeneichner, Alexander C.T. Geppert, Daniel Brandau, Tilmann Siebeneichner, Alexander C. T. Geppert(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

While one cause was the revelations coming from Russia about the true nature of the Soviet space program, the changing views of the early reach into space broadened considerably. For example, historian Walter A. McDougall in 1985 famously called Sputnik – the event that initiated The Space Race – a ‘saltation, an evolutionary leap’ for humankind. Just twelve years later, in 1997, McDougall disavowed his assessment and instead said Sputnik was an ‘ephemeral episode in the larger history of the Cold War.’ 50 In other words, Sputnik, which rode into space on an R-7 ICBM, was a product of the larger military and nuclear standoff of the Cold War years. Other historians and scholars have re-evaluated Sputnik and its meaning, with many questioning whether the American reaction to Sputnik extended beyond the political, media and military fields. 51 They have taken fresh looks at the Sputnik crisis in the United States, sometimes offering conflicting viewpoints. For example, in his analysis of how Eisenhower used fears of nuclear war to advance his agenda, Ira Chernus has shown that the Sputnik controversy was the result of ‘nearly five years of frightening Cold War rhetoric’ from the Eisenhower administration, while Yanek Mieczkowski, in his sympathetic treatment of Eisenhower’s response to Sputnik, did not raise this issue and noted that Eisenhower was often criticized for passivity. 52 The wider changes to spaceflight history were labeled by Roger Launius as the ‘New Aerospace History,’ which aimed to move beyond concentration on individual rockets or spacecraft to wider social, political and cultural issues relating to aircraft, missiles and space vehicles - eBook - ePub

When Science and Politics Collide

The Public Interest at Risk

- Robert O. Schneider(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Praeger(Publisher)

CHAPTER TWOThe Space Race: A Marriage of Necessity

As he looked into the October sky from his Texas ranch, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson strained to catch a glimpse of “that object which had been cast into the outer reaches of the world.” For LBJ, it represented a “defeat as serious as Pearl Harbor.”1The launching of Sputnik 1 by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957, rudely awakened Americans to a rapidly developing space age. Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, brought the Soviet Union into the technological spotlight and demonstrated that the country was capable of impressive new technological feats. It also sent a shock wave through the American public. Sputnik caused deep concerns among Americans who had felt a sense of technological superiority amid a postwar economic boom. Was the United States falling behind? Could Sputnik be a play on the part of the Soviets to put arms in space? Is space a necessary place to compete for world prestige?Initial reactions to the Soviet accomplishment included shock, dismay, and alarm. Senator Henry Jackson called Sputnik a “devastating blow to U.S. scientific, industrial, and technological prestige.” Senator Mike Mansfield called for a new Manhattan Project to regain missile superiority over the Soviet Union. Adlai Stevenson, Democratic presidential nominee in 1952 and 1956, expressed a concern shared by many when he said that “not just our pride but our security is at stake.”2 The American public was also quick to react. Six months prior to the launching of Sputnik, only one in five Americans could give a reasonably accurate description of a space satellite. Within weeks after Sputnik, 90 percent knew what a satellite was. Indeed, people the world over demonstrated a keen awareness of and interest in the Soviet accomplishment. Worldwide reaction suggested a growing respect for the Soviets.3Americans typically expressed concerns about falling behind the Soviets technologically, about possible U.S. military vulnerability, about U.S. scientific prowess, and about confidence in American leadership on the world stage. Indeed, there was a sense of urgency in American public opinion and a strongly felt need to respond to what was perceived to be a crisis. For its part, the Eisenhower administration was neither shocked nor alarmed. Defense Secretary Charles F. Wilson called Sputnik “a neat scientific trick.” President Eisenhower himself, initially concerned about the possible military significance of Sputnik, was persuaded that there was nothing that justified concern. The administration’s first public response concluded that there was no need to alter the U.S. research and development program with regard to either space technology in general or to ballistic missiles in particular. The president’s immediate concern was, in his words, to “find ways of affording perspective to our people and so relieve the current wave of near hysteria.”4 - eBook - ePub

Reconsidering Sputnik

Forty Years Since the Soviet Satellite

- Roger D. Lanius, John M. Logsdon, Robert W. Smith(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

ART 1—INTRODUCTIONSpace Flight in the Soviet Union

Roger D. LauniusWith the launch of Sputnik on October 4, 1957, a scrambling for explanations ensued about how the Soviets had suddenly bested the United States, arguably the most technically advanced civilization the world had ever known. In fact, as the essays in this part of this book demonstrate, the dream of space flight had enjoyed a long tradition in the Soviet Union. Beginning near the turn of the twentieth century two important developments converged in Russia that made possible Sputnik's extraordinary success: science fiction literature sparked the enthusiasm of a generation of engineers and technicians who longed for the possibility of actually going into space and exploring it firsthand, even as rocket technology began to mature and thereby brought a convergence of dream with likelihood.1Peter Gorin traces the relationship of these two elements during the pre-Sputnik era in the Soviet Union. He begins with the roie of a small group of pioneers who developed the theoretical underpinnings and the technical capabilities of rocketry in the first half of this century. Four towering figures have been held up as the godfathers of modern space exploration, largely because of their work on rockets. Gorin finds that the the most significant for the Soviet Union, if not the earliest, was Konstantin E. Tsiolkovskiy. The others included the German Hermann Oberth, the American Robert H. Goddard, and the Frenchman Robert Esnault-Pelterie. Collectively, these men developed theories of rocketry for space exploration, experimented with their own rockets, and inspired others to follow in their footsteps. - eBook - ePub

Space Weapons and U.S. Strategy

Origins and Development

- Paul B. Stares(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

3Eisenhower and the Space ChallengePerhaps the starkest facts which confront the United States in the immediate and foreseeable future are (1) the USSR has surpassed the United States and the free world in scientific and technological accomplishments in outer space, which have captured the imagination and admiration of the world; (2) the USSR, if it maintains its present superiority in the exploration of outer space, will be able to use that superiority as a means of undermining the prestige and leadership of the United States; and (3) the USSR, if it should be the first to achieve a significantly superior military capability in outer space, could create an imbalance of power in favor of the Sino-Soviet Bloc and pose a direct military threat to U.S. security.The security of the United States requires that we meet these challenges with resourcefulness and vigor. Introductory Note to NSC 5814/1, “U.S. Policy on Outer Space”, 20 June 1958INTRODUCTIONThe period immediately following the launch of Sputnik was a challenging time for the Eisenhower administration. Despite repeated warnings, it was still caught unprepared for the crisis that Sputnik would cause. Public and congressional concern at the implications of the Soviet achievement for the prestige and security of the United States immediately created pressures for an accelerated and expanded space effort. What Eisenhower had hoped would be a relatively leisurely and orderly US entry in space was transformed overnight into a national obsession to wrest the lead from the Soviet Union.This imperative posed additional challenges. New organizational structures and procedures had to be formed to manage the expanded space programme. A complete review of US interests, priorities and goals in the exploration of space was also necessary. Moreover, the exaggerated fears of Soviet intentions after Sputnik spurred a whole range of space weapon proposals to counter the perceived threat. These had to be assessed not only for their military utility and technical feasibility but also for their long-term impact on the future use of space. These, then, were among the most important problems that faced the Eisenhower administration from 1957 to 1960. - eBook - ePub

The War of Nerves

Inside the Cold War Mind

- Martin Sixsmith(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Wellcome Collection(Publisher)

20The Space Race

By mid 1958, the Americans were ready to respond to the blow to their prestige inflicted by Sputnik. The presidential directive to the National Security Council establishing the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NSC 5814/1, made clear what was expected. NASA must ‘judiciously select’ projects that would have ‘a favorable world-wide psychological impact’.1 Political and scientific think tanks were tasked with assessing what measure of psychological triumph by the US it would take to trump Moscow’s initial successes. The recommendation of the Aeronautics and Space Council was clear: manned spaceflight.To the layman, manned space flight and exploration will represent the true conquest of outer space and hence the ultimate goal of space activities. No unmanned experiment can substitute for manned space exploration in its psychological effect on the peoples of the world. There is reason to believe that the Soviets, after getting an earlier start, are placing as much emphasis on their manned space flight program as is the US.2They were indeed. As early as November 1957, the Soviet ‘chief designer’, Sergei Korolev, had followed up his Sputnik triumph with another first. When Nikita Khrushchev asked if Sputnik-2 could be ready for launch by the fortieth anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution on 7 November, Korolev replied that it could and, what’s more, he could offer something extra – a dog.Khrushchev saw the potential for headlines. His initial scepticism about Korolev’s space programme had evaporated as he witnessed the discomfort it caused the West. He told Korolev to spend whatever it took. Sending a dog into space was the first step towards sending a man, and both Moscow and Washington knew that was the target to aim for.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.