History

Naval and Arms Race

The naval and arms race refers to the competition between nations to build up their naval forces and military capabilities, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This period saw major powers such as Britain, Germany, and the United States vying for naval supremacy, leading to an escalation in military spending and technological advancements in naval warfare.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

Related key terms

1 of 4

Related key terms

1 of 3

10 Key excerpts on "Naval and Arms Race"

- eBook - ePub

Explaining Contemporary Asian Military Modernization

The Myth of Asia's Arms Race

- Sheryn Lee(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

2Rooted in European and American scholarship, the arms race concept attempted to understand arming dynamics between states and coalitions leading up to the First and Second World War and the Cold War bipolar US–Soviet relationship. The notion of arms racing served two primary functions: first, as an analytical concept to explain and identify abnormal strategic behaviour between states and, second, as a political advocacy tool to influence political debate and armaments decisions. The conventional arms build-up by France and the British Commonwealth between 1840 and 1866 is considered the first competition in armaments in the modern era. Then, France and Great Britain continued to improve their arsenals of revolvers, rifles, machine guns, guns and howitzers, engaging in a qualitative competition to increase the speed of fire, the accuracy of aim, range, weight and explosive force of the projectiles. From 1884 onwards, not only did the number of warships increase, but crucial qualitative characteristics—size and speed, the calibre and range of guns and protective belts of armour—also evolved rapidly. The first recorded use of the term arms race dates to 20 March 1894 in the British House of Commons, when Liberal member of parliament William Randal Cremer decried large increases in the navy’s budget as a “mad race of naval expenditures.”3 Victorian liberals and their socialist counterparts in Western Europe “saw excessive arms expenditure as a tragic diversion of wealth away from social goods and productive investments and as symptomatic of the twin evils of militarism and authoritarianism and the excesses of capitalism and imperialism.”4By the early 20th century, the term arms race became a popular media and scholarly description of competitive naval arming dynamics between Britain and Wilhelmine Germany. Particularly the frenzied construction of the Dreadnoughts, and later super-Dreadnoughts, which continued until the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, fed this narrative. Although the British were the first to commence building of Dreadnought battleships, it was German admiral Alfred von Tirpitz’s perceived intentions that resulted in strategic competition between Germany and the British Empire.5 The German construction of Dreadnoughts rendered obsolescent the 75 pre-Dreadnought British battleships and armoured cruisers, which led to England constructing Dreadnoughts to restore its primacy at sea. In 1908, Kaiser Wilhelm wrote to the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Tweedmouth: “Admiral Fisher and the Press had at once announced that [the Dreadnought] was capable of sinking the whole German Navy. These statements had forced the German government to begin building ships of a similar type, to satisfy public opinion.”6 Tirpitz and the Kaiser defended the First and Second German Navy Laws that doubled the fleet as not building against Britain but as necessary to guard the German Empire’s coasts and colonies. The British Empire responded to the challenge by launching a naval build-up to restore a favourable balance.7 The later introduction of the submarine and its major impact on the exercise of naval power meant both the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy) and the Triple Entente (the United Kingdom, France and Russia) swiftly expanded their submarine fleets.8 - eBook - ePub

Strategy in Asia

The Past, Present, and Future of Regional Security

- Thomas G. Mahnken, Dan Blumenthal(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Stanford Security Studies(Publisher)

Indeed, during that period a sizable body of literature on arms races emerged, driven by interest in competition between the United States and Soviet Union. Samuel Huntington describes an arms race as “a progressive, competitive peacetime increase in armaments by two states or coalitions of states resulting from conflicting purposes or mutual fears.” 3 Subsequently, Colin Gray came to define an arms race as “two or more parties perceiving themselves to be in an adversary relationship, who are increasing or improving their armaments at a rapid rate and restructuring their respective military postures with a general attention to the past, current, and anticipated military and political behavior of the other parties.” 4 Accordingly, an arms race has four basic elements. First, it must involve at least two parties. Second, each party must develop its force structure with reference to the competition. Third, each must compete with the other in the quantity or quality of their respective militaries. Finally, interactions must lead to a rapid increase in the quantity or quality of weapons. Arms competitions can also vary considerably in both scope and pace. With this fact in mind, Barry Buzan coined the term arms dynamic to refer to pressures that make nations buy military capabilities and enhance their quantity and quality over time. 5 External Sources of Competition One group of scholars emphasizes external sources of arms competition. The most common and simplistic formulation is the action-reaction model, which stipulates “that states strengthen their armaments because of the threats the states perceive from other states. The theory implicit in the model explains the arms dynamic as driven primarily by factors external to the state.” 6 Basically, it holds that the search for security, together with uncertainty and worst-case estimates of enemy intentions and capabilities, will yield efforts to amass ever-greater stockpiles of weaponry - eBook - ePub

- Andreas Herberg-Rothe(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Ibidem Press(Publisher)

An arms race is defined here as a competition among rivals to surpass (or keep pace with) each other militarily. Arms races typically involve several armaments programs, and can take on both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. They often produce accidental asymmetries or imbalances in military capabilities due in part to the nonlinear nature of technological change and to such factors as economic and geographic resources and strategic alliances. Britain, France, Russia, and Germany, for instance, competed aggressively in the first modern arms race; but Britain placed more emphasis on sustaining her naval supremacy, while the others ultimately gave higher priorities to land power. Air power was an entirely new domain, and while pundits such as H.G. Wells (The Air War , 1908) speculated as to whether it might become a game-changer, it was not technologically mature enough by 1914 to upset the balance of power.Passage contains an image

Part II

The first modern arms race essentially started with Great Britain’s naval bill of 1889; the bill formally announced the “two-power standard,” which meant the Royal Navy would maintain a fighting power “at least equal to the strength of any two other countries.”[17]At the time, the Royal Navy was already as strong as the next two largest navies, the French and Russian. However, the bill called for an additional 10 battleships, 42 cruisers, and 18 torpedo gunships to be built over the next five years.[18] It was clearly an attempt at general deterrence designed to guarantee British naval supremacy through the fin de siècle. Nevertheless, maintaining the two-power standard was an ambitious task; even a modest expansion by either France or Russia would force Britain to redouble her efforts, which in fact happened. Both France and Russia increased their naval armaments programs in the early 1890s in direct response to British expansion. Britain, in turn, responded by adding 3 more battleships to her original target of 10, and by implementing a new five-year plan designed to add 12 additional battleships and 20 cruisers by the end of the century. - eBook - ePub

An Improbable War?

The Outbreak of World War I and European Political Culture before 1914

- Holger Afflerbach, David Stevenson, Holger Afflerbach, David Stevenson(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Berghahn Books(Publisher)

3 Moreover, armaments had a dual quality. As Janus-faced instruments, they had aggressive and defensive functions. It is in this context that we must place the debate about armaments in the period prior to 1914. The Russian note of 1898 did not only mention the diversion of civil expenditure to military purposes and the potential impact on the economy and on social welfare. It also hinted at the ultimate danger, the risk of real, shooting war (“cataclysm”). It is true that at the time, naval and land armaments were still only loosely interconnected, and that air warfare remained at a nascent stage. Although the great powers basically accepted armaments competition as a fact of life, smaller states were involved in it only to a limited extent. And although alliances mattered, statesmen in general did not think of coalitions as vehicles for common military preparation against an opposing coalition—at least before the turn of the century. This changed, however, in the wake of the first Moroccan crisis of 1905-6, after which Anglo-French military staff talks began and, somewhat later, an Anglo-French naval agreement was reached, while in the opposing bloc exchanges between the German and Austro-Hungarian general staffs were renewed. National armament efforts and the emergence of a dangerous polarization between two coalitions were prime reasons for the outbreak of war in 1914.Despite these factors, it is important to realize that these interconnections that are so clear in hindsight might well have been viewed differently in contemporary assessments. The competition between major powers over armaments can be seen as regional, national, or even multi-national races that served to reinforce the rationale for each involved party and to justify an increase in arms to keep up with one's neighbor or neighbor's ally. Controlling armaments and especially the enormous financial burden of armaments was therefore a dream of many contemporaries. When the British delegate to the Second Hague Peace Conference introduced arms limitation proposals, he praised them in words from Virgil's eclogue: - eBook - ePub

- Michael Sheehan(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

On those many occasions when reliable allies are not available, states have been encouraged either to issue an arms race challenge, or to accelerate previously low-gear arms race activity, following upon an apparent military-technological opportunity. This opportunity may take the form of diminished activity by the rival or, more likely, the successful development of a technology that offers to negate, or render of less significance, an existing quantitative or qualitative imbalance. As examples of this, we could cite France versus England in the 1840’s and 1850’s; Germany versus England after 1906; and the Soviet Union’s missile development and procurement policy in the middle 1950’s and from 1963 to 1970.This last example is a very contentious one. It has been argued that the great increase and improvement in the Soviet ICBM’s and SLBM’s (submarine-launched ballistic missiles) apparent in the late 1960’s reflected decisions taken in the period 1961-1965.5 Thus, the building programs have reflected a sustained determination to match and perhaps to out-build the United States. A different interpretation would be that the Soviet Union was encouraged to challenge the American lead by the quantitative restraint shown by the Americans after 1964. This latter view is a direct repudiation of the idea that an arms race may be restrained by the operation of a “sympathetic parallelism.”6With regard to the functions of a competition, we may choose to view an arms race as an alternative to war, to be planned, waged, and then won or lost–with due reward br punishment. A more apocalyptic view would be that an arms race is not an alternative to war, but is a preparation for war. Thus, instead of an arms race being a bloodless ritual of preparation,7 it is a race for that measure of military superiority that would allow for the exploitation of arms race victory in war-waging success.The choice of an overall view of an arms race is directly dependent upon the major empirical referents. The introduction of nuclear weapons has made a very considerable difference to the conduct of an arms race. Indeed, one leading interpreter of Lewis Richardson’s theory of arms races has developed Richardson’s idea of submissiveness, originally applied to the inter-war period, with the argument that nuclear weapons have introduced an unprecedented fear factor into the post-1945 nuclear arms race.8 However, even if we grant the quantum jumps in the time-scale of contemporary war and the destruction that could be imposed by nuclear weapons, it would still be a gross oversimplification to assert that prior to 1945 arms races were more often than not serious preparations for war, whereas since 1945 arms races involving nuclear powers are essentially a form of diplomatic activity, remote from considerations of the conduct and termination of war. Two vital complications must be noted. First, competition in missiles, since at least 1959, bears an important resemblance to races between land forces prior to 1945. Both kinds of races are what can be termed “damped” or “non-self-aggravating” arms races.9 In other words, the needed ratio of offense to defense is such that a strategy of militarily exploitable superiority is prohibitively expensive.10 - eBook - ePub

International Relations since 1945

East, West, North, South

- Geir Lundestad(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications Ltd(Publisher)

In addition, an entirely new range of weapons was developed: the nuclear weapons. These weapons had a destructive capability that was unique. Humanity might face its own demise if a new major war broke out. Nuclear weapons and the new launchers, long-range bombers, and missiles united the world. A future war could affect everyone – military or civilian, belligerent or neutral.Moreover, the pace of new invention was faster than it had ever been. The question of armaments still had a quantitative dimension, but the qualitative aspect played an increasingly greater role. More and more new weapons systems were developed. Those involved were constantly preparing for the worst possible scenario that could materialize, not only tomorrow, but 10, 15, or 20 years into the future.To simplify, it can be said that there are two main interpretations of the motivating forces behind the arms race. The first one places greatest emphasis on the foreign policy environment. The arms race between East and West, like previous arms races, arose from international anarchy (anarchy in the sense that there is no supranational body that can effectively regulate relations between nations). Distrust and fear cause nations to try to protect themselves by amassing armaments. The competing sides then impel each other on through a pattern of action and reaction. Initiatives by one side result in counter-measures on the other side, which again lead to new measures, and so on. Thus the arms spiral continues.The other interpretation places greatest emphasis on internal causes. Armament is pursued to satisfy various pressure groups. The military establishment seldom or never gets enough weapons. The weapons industry endeavors to earn profits and secure employment. These groups in turn receive support from politicians. According to this theory, there were actually two parallel arms races, one in the West and one in the East.There are also combinations of these two main views. They provide the basis for the present discussion. Primary emphasis will be placed on the foreign policy environment and the pattern of action and reaction. However, a number of other factors also contributed to the arms race. Economic trends, prevailing economic theories, and the priority given to defense within the total national economy were significant. The same was true of technological developments and the influence of scientists, the military, and the weapons industry. The relative importance of the various factors could vary considerably from case to case. It also makes a difference whether the focus is on total arms expenditure or the development of specific weapons projects. Internal factors probably played a greater role for specific weapons projects than for aggregate defense expenditure, which is the primary focus of this presentation. - eBook - ePub

The Last Century of Sea Power, Volume 2

From Washington to Tokyo, 1922–1945

- H. P. Willmott(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Indiana University Press(Publisher)

PART 1 NAVAL RACES AND WARS CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION: WASHINGTON, LONDON, AND TWO VERY SEPARATE WARS, 1921–1941 A RMS RACES ARE NOT the cause of rivalries and wars but rather the reflection of conflicting ambition and intent, though inevitably they compound and add to these differences. The First World War was not the product of Anglo-German naval rivalry, though this was one of the major factors that determined Britain’s taking position in the ranks of Germany’s enemies, and most certainly it was a major factor in producing the growing sense of instability within Europe in the decade prior to 1914. But if the naval race was indeed one of the factors that made for war in 1914—although it should be noted that the most dangerous phase of this rivalry would seem to have passed by 1914—then there is the obvious problem of explaining the war in 1939–1941, in that the greater part of the inter-war period, between 1921 and 1936, was marked by a very deliberate policy of naval limitation on the part of the great powers. Admittedly the arrangements that were set in place in various treaties had lapsed by 1937, and a naval race had begun that most certainly was crucially important in terms of Japanese calculations in 1940 and 1941 and indeed was critical in the decision to initiate war in the Pacific. In summer 1941, as the Japanese naval command was obliged to consider the consequences of its own actions and the full implications of the U.S. Congress having passed the Two-Ocean Naval Expansion Act in July 1940, the Imperial Navy, the Kaigun, was caught in a go-now-or-never dilemma, and it, like its sister service, simply could not admit the futility and pointlessness of past endeavors and sacrifices - eBook - ePub

Logic of Conflict

Making War and Peace in the Middle East

- Steven Greffenius(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

That is because arming is not the only means available to decision makers for protecting national security, nor is it the only means by which nations compete with or threaten one another. Because arms competitions are part of relationships that encompass all kinds of interests and worries, their causes and consequences can only be understood by taking these other factors into account. They are not, as the very term arms race implies, mechanical processes that operate independently of politics. Churchill and Wilson on Politics and Arms Two figures from the history of international relations, both historians and statesmen themselves, greatly influenced twentieth-century views about the relationship between arms and interstate conflict. The stands they took exemplify the double-edged nature of arms and arming. Winston Churchill correctly saw the threat Hitler posed to European safety and advocated rearmament to meet it. He argued that Britain’s determination to stop Hitler would be lost on Germany were Britain incapable of carrying out its policy. Thus the relationship between Britain and Germany during the 1930s, in his view, was both a political one and a military one. The intellectual pedigree of this view goes back at least to Karl von Clausewitz, a Prussian army officer who wrote in the first half of the nineteenth century. In Clausewitz’s view, political and military factors in an interstate relationship act upon each other, but the use of force is always subordinate to politics. Hence, diplomacy encompasses warfare. In this argument, then, armaments are one part of a larger national security picture. Woodrow Wilson fathered another perspective that arms themselves create undue insecurity among states. He observed the outcome of the arms competition that preceded World War I and concluded that the very means states use to protect themselves too often bring about their ruin - Desmond Ball(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

48(ii) Possible International Restraints : The 1991 Gulf War not only brought about a sharp increase in arms sales agreements by Middle East countries;49 it also created widespread interest in advanced weapons systems such as surveillance, electronic intelligence and target acquisition equipment. Because some countries assume that the availability of these weapons systems might not last for much longer, there has been a general perception that purchases should be made soon, while stocks last and before international constraints are imposed. China is reportedly ‘moving quickly to acquire as much military capability as possible before the international community closes the door on the sale of advanced military technology’.50The Dynamics of Arms Proliferation

The dynamics of interactive arms proliferation occurs primarily when there is a very rapid rate of acquisition, with the participants stretching their resources in order to ensure that they remain ahead in the acquisition process. Reciprocal dynamics in the defensive and offensive capabilities of one participant are then matched by attempts to counter the advantages thought to be gained by another. Thus, the continued acquisition of new weapons capabilities becomes an interactive process, and can be termed ‘an arms race’.The scope and characteristics of the regional military acquisition programmes as described here do not indicate that the dynamic aspects of the weapons acquisition process are at work among the countries of this region. Hence, the current arms procurement situation does not conform to the generally accepted definition of the term ‘arms race’. There are only a few clear cases where specific acquisitions by one country have led to either imitative or counter acquisitions by others. Perhaps the best example is the acquisition of F-16 fighters by several countries in Southeast Asia. In this case, Singapore's decision to purchase F-16s served as a stimulant for subsequent Indonesian and Thai F-16 acquisitions. It is also believed to have influenced Malaysia's interest in a strike fighter.51 Even in this instance, however, other considerations were at least as strong. Emphasis on air defence and strike capabilities to enhance self-reliance had been growing in the region. Capabilities are required to defend the air and sea approaches, to conduct armed surveillance patrols over EEZs, and to demonstrate an effective commitment to actively contend claims in disputed maritime areas. Last, the prestige that is attached to the acquisition of modern technology cannot be overlooked in this case. For Thailand, in so far as any interactive dynamics were involved, the F-16 acquisition was more to offset the acquisition of MiG-23s by Vietnam than to counter the programmes of its ASEAN neighbours.52- eBook - ePub

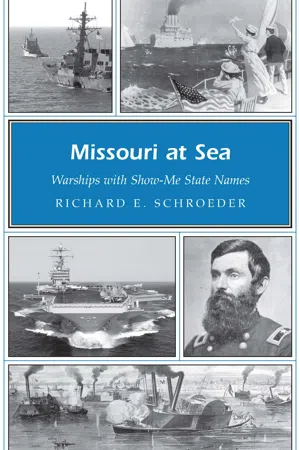

Missouri at Sea

Warships with Show-Me State Names

- Richard E. Schroeder(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- University of Missouri(Publisher)

CHAPTER THREE

The Great Naval Arms Race and the First World War

Decline and Rebirth—A New Missouri and Two Named St. LouisAt the end of the Civil War the United States had the most experienced, most powerful army and navy in the world, but within two years hundreds of ships had been cut from the huge 671 ship wartime fleet. In 1865 the navy had 7,000 officers and 51,500 men, but by December 1867 only 2,000 officers, 12,000 men, and 103 ships remained. When David Farragut died in 1870, David Dixon Porter became senior admiral of the navy until his own death in 1890, and the U.S. Navy returned to the comfortable prewar practice of using tiny American squadrons to protect American commercial interests around the world.The American navy had experimented with many technological advances, and steam power, armor, gun turrets, naval guns, and ammunition had quickly improved in the laboratory of a four-year war. European naval experts had watched the American experience with intense interest, and the great European powers quickly exploited rapid technological developments in ship design, steam power, steel-making, and weaponry to build ever-more-advanced warships. At a time when Admiral Porter was ordering American ships to use only sail and threatening to charge captains personally for the coal if they ran their engines, the British were abandoning sail for coal and building steam-driven armored ships, like Dreadnought in 1875, that were clearly the direct grandparents of the great battleships of the twentieth century, including the last Missouri. These new British battleships carried their big guns in turrets in front of and behind their bridges and smokestacks and were designed to destroy other battleships in the open seas anywhere in the world.Over the next decades European nations spent hundreds of millions of dollars building even more powerful battleships and increasing their war fleets. Europe competed not only for the strongest fleets, but for the most foreign colonies and naval bases in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Ocean. Few Americans were willing to pay to join the race for more modern warships and bigger fleets. Indeed, when Americans thought there might be war with Spain in 1873 over brutal Spanish treatment of their Cuban colony, Admiral Porter said “it would be much better to have no navy at all than one like the present,” which was much weaker than the Spanish fleet. As late as 1889 the U.S. Navy ranked twelfth in the world in size, weaker than the navies of such countries as Turkey, China, and Austria-Hungary.

Explore more topic indexes

Explore more topic indexes

1 of 6

Explore more topic indexes

1 of 4