What is Monetarism?

MA, Economics (Renmin University of China)

Date Published: 16.03.2023,

Last Updated: 14.09.2023

Share this article

Defining Monetarism

According to the famous monetarists Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz,

Money is a fascinating subject of study because it is so full of mystery and paradox. The piece of green paper with printing on it…will enable its bearer to command some measure of food, drink, clothing, and the remaining goods of life. (1963 [2008])

Milton Friedman, Anna Jacobson Schwartz

Money is a fascinating subject of study because it is so full of mystery and paradox. The piece of green paper with printing on it…will enable its bearer to command some measure of food, drink, clothing, and the remaining goods of life. (1963 [2008])

Among other things, monetarists assert that controlling the growth of the stock of money, or money supply, is vital for maintaining the stability of the economy. Friedman and Schwartz were not the first nor the last monetarists on the scene. Other notable proponents include Karl Brunner, who coined the term, at least two chairs of the Federal Reserve, Paul Volcker and Alan Greenspan, and even former British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher.

Generally, the rise of monetarism, which came to prominence in the 1970s and 80s, is seen as a direct response to the dominance of Keynesian economics in the post-war period. In A Concise History of Economic Thought [2016], Vaggi and Groenewegen state that,

[T]his critical stance towards contemporary Keynesian policy thinking is a crucial aspect of monetarism…Monetarism has therefore been accurately described as a counter-revolution in economics designed to restore money supply as a key macro-economic policy variable.

G. Vaggi, P. Groenewegen

[T]his critical stance towards contemporary Keynesian policy thinking is a crucial aspect of monetarism…Monetarism has therefore been accurately described as a counter-revolution in economics designed to restore money supply as a key macro-economic policy variable.

Because of this, you often see monetarism described, not in terms of its contributions to the advancements in economic thought, but rather in terms of its objections to Keynesianism.

Today, economic theory and policy making is rarely divided neatly into proponents of monetarism and proponents of Keynesianism, but the legacy of their former battles remain. Take debates over how to set interest rates, the relative importance of monetary policy vs. fiscal policy in stabilising and growing the economy, or discussions about the relationship between inflation and unemployment. Monetarist theories did a lot to further our understanding of these issues.

So, what exactly was the monetarist counter-revolution? Let’s start with an example.

Keynesianism vs. Monetarism: The Great Depression

A useful introduction to the two approaches can be seen in their explanations for the Great Depression (1929-1933). John Maynard Keynes, one of the most important figures in modern economics, horrified by the tragedy of the Great Depression, argued that its cause lay in a huge fall in aggregate demand. He proposed that government intervention to stimulate aggregate demand was the answer. He didn’t agree with the classical laissez-faire approach, i.e., that it is better to let market forces run their course as economies will naturally return to a position of equilibrium in the long run. He saw that as irrelevant, famously writing that:

In the long run we are all dead.

Instead, he believed that governments should play an active role in bringing economic stability, softening the ups and downs of the business cycle. Fiscal policy, which involves managing the economy primarily through adjusting government spending and tax policies, was his main tool. Many felt his arguments were borne out, as only massive government spending and other expansionary policies, driven by World War II, ended the period of the Great Depression. This led to the dominance of Keynesian economics from the 1950s onwards.

As for Friedman and Schwartz, their investigations into the money supply led them to another interpretation. Their analysis showed that the Great Depression coincided with a huge drop in the money supply, which refers to the total currency and other liquid assets in the economy. They asserted that

[T]he monetary collapse was not the inescapable consequence of other forces, but rather a largely independent factor which exerted a powerful influence on the course of events…The contraction is in fact a tragic testimonial to the importance of monetary forces.

They believed the way out of the Depression should have been through interventions to increase the supply of money. In their eyes, the blame for the economic collapse and its longevity sat squarely on the shoulders of the Federal Reserve and the banking system.

In more general terms, they argued that changes in the money supply are not a result of changes in other economic variables, rather that “the direction of influence must run from money to income”. They concluded that the money supply has a direct influence on economic activity, indeed it determines the rate of economic growth. As to why they thought this, here the devil really is in the details.

Let’s start with the Quantity Theory of Money.

The quantity theory of money

The theory that underpins monetarist explanations of the relationship between money supply and economic growth is the Quantity Theory of Money. This is often represented as:

MV = PQ

where M is the money supply,

V is the velocity of money (the rate at which money is exchanged in an economy),

P is the average price for goods and services,

and Q is the quantity of goods and services produced.

Monetarists took V as relatively predictable, which was shown by Friedman and Schwartz’ work on the history of the money supply, therefore the money supply (M) becomes the main driver of prices and output, i.e., economic growth.

While Keynesian economists do not dispute the truth of this equation, they do dispute the argument that V is stable. If V is not stable, the relationship between money supply and economic output becomes much weaker. Keynesians do see a relationship between the money supply and Gross Domestic Product (GDP), however it’s an indirect relationship. An increase in the money supply can push down the interest rates (all other things remaining equal), which in turn can encourage consumption and investment, pushing up aggregate demand and ultimately driving economic growth. For pure Keynesians, it always comes back to the theory of aggregate demand. For more on how short- and long-run aggregate demand and supply works, see our article on the AD-AS Model.

The monetary growth rate

If we assume, as the monetarists did, that changes in the money supply are the main driver of changes in prices and output, we start to see the policy implications of monetarist theory. Friedman famously stated that “[i]nflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.” His statement refers to the Quantity Theory of Money, i.e. if the growth of M rises faster than the growth of Y, there will be inflation. As the main goal of monetarist theory was to achieve economic stability in terms of growth and prices, the argument followed that policy should target a steady growth in the supply of money, matching it to expected economic growth rates, to achieve this.

According to Greenlaw, Taylor, and Shapiro in Principles of Macroeconomics for AP Courses [2017], most monetarists actually advocated for minimal government intervention, believing that “with the long and variable lags of monetary policy, and the political pressures on central bankers, central bank monetary policies were as likely to have undesirable as to have desirable effects.” In their minds, the best method for minimising any undesirable effects was to create an explicit and fixed target for the growth of the money supply, which central banks would work to achieve over the long term. This would also keep inflation low and help to manage expectations of price and wage inflation, which they argued also affects economic activity. They did not agree with the Keynesian view that governments should use discretionary policy interventions to manage fluctuations in the short-term (as mentioned above, many Keynesians believed that the long run may never arrive).

Money supply, inflation, and unemployment

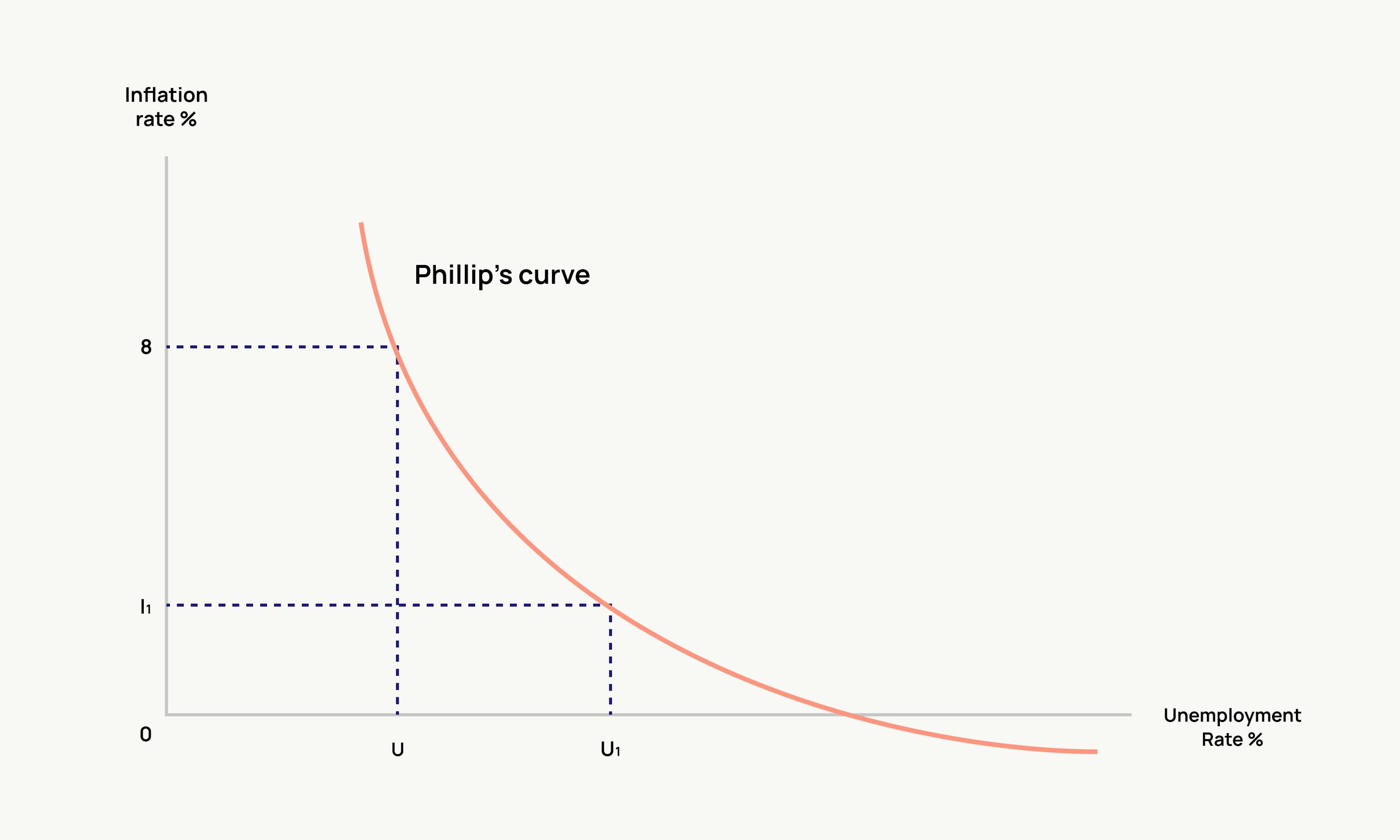

Another area of debate was the relationship between inflation and unemployment. The main economic model used at the time was the Phillips curve, which posits a positive relationship between employment and inflation. This is on the basis that any attempt to reduce unemployment will have inflationary effects. The theory goes that the increase in demand required to achieve low unemployment would increase demand for labour and push up wages. These increased business costs would be passed onto the consumer by firms in the form of higher prices.

As Sylvie Rivot explains in her book Keynes and Friedman on Laissez-Faire and Planning [2013], Keynesian economists used this to argue that policy makers could,

’Purchase’ lower unemployment through demand policy provided that ongoing inflation was tolerated…What is more, the relationship was considered reversible: the bargaining between inflation and unemployment could be done either way.

Sylvie Rivot

’Purchase’ lower unemployment through demand policy provided that ongoing inflation was tolerated…What is more, the relationship was considered reversible: the bargaining between inflation and unemployment could be done either way.

Figure 1 below shows a graphical representation of the Phillips curve.

Figure 1

In the 1970s, the US and the UK experienced both high inflation and high unemployment, known as stagflation. Monetarists jumped on this as a failure of Keynesian theory. They argued that the Phillips curve did not account for several key principles. Firstly, they believed that individuals were not as “short-sighted” as Keynesians made them out to be. Individuals’ expectations need to be taken into account.

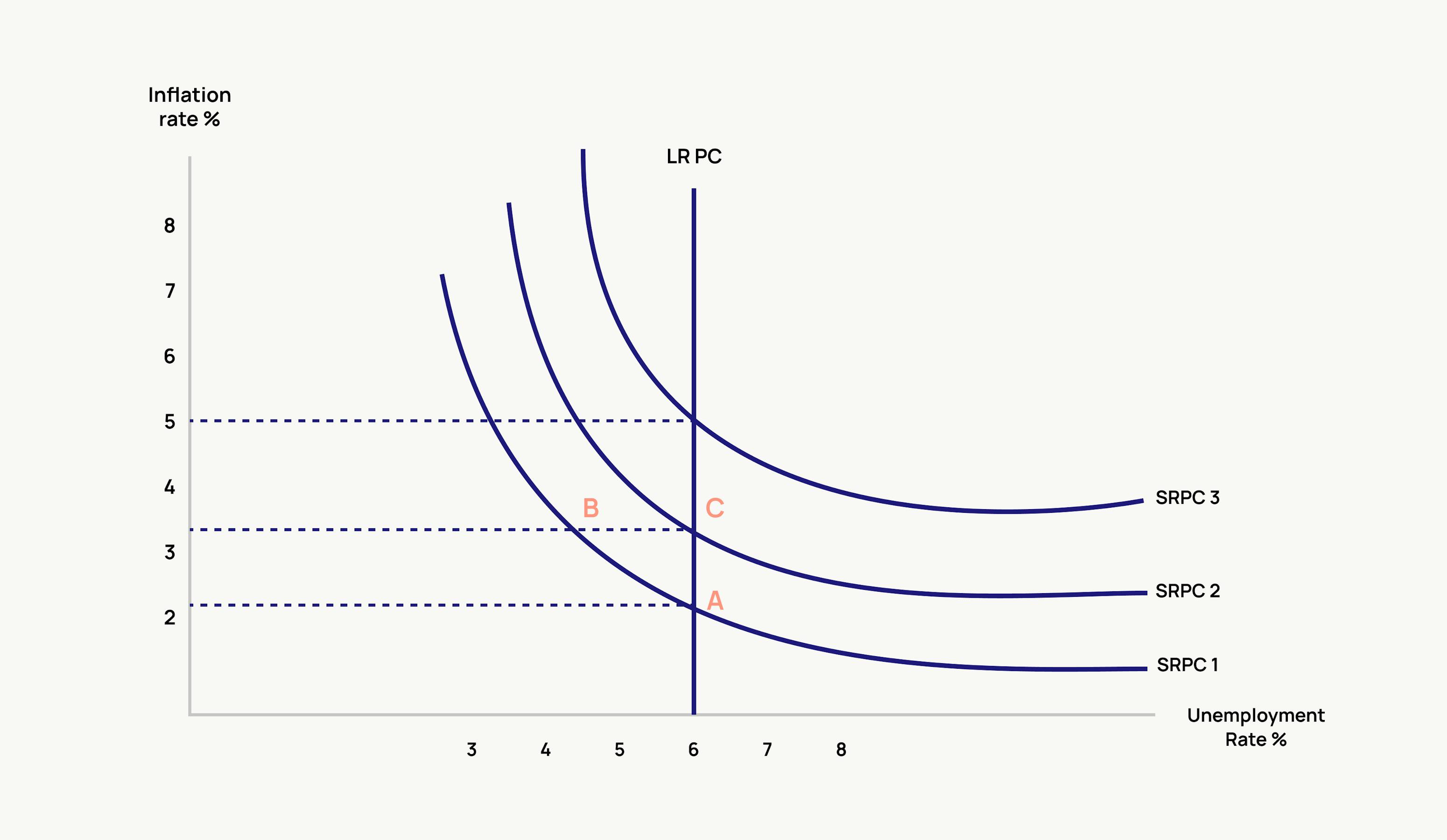

Secondly, they concluded that the positive relationship between employment and inflation would only exist in the short term. In the long run, there would be no trade-off between unemployment and inflation as the unemployment rate would always shift back to its long run natural state. Figure 2 below shows these changes.

Figure 2

Imagine that we are first at point A. This level of unemployment is deemed unacceptable to the government, therefore, policies to stimulate aggregate demand are put in place, which leads to more demand for labour and more employment. As a consequence, this drives up nominal wages, or wages that haven’t been adjusted for inflation, and, as explained above, causes inflation to rise. This is shown by a movement from point A to point B in Figure 2. Monetarists argue that workers will then take account of the higher inflation and realise that the purchasing power of real wages, or wages adjusted for inflation, has decreased. Thus workers will reduce the amount of labour they want to supply at this wage point and, unless real wages are increased, the curve will shift from SRPC1 to SRPC2. We have now gone from point B to point C; unemployment has shifted back to its original level but now with higher inflation.

The monetary position on unemployment lays out the case for a ‘natural rate of unemployment’, which is where the actual rate of inflation and the expected rate of inflation are equal. This is the vertical long run Phillips curve in Figure 2 above. On this curve, the economy is at the natural rate of unemployment, where expectations are in line with the current rate of inflation. This again feeds the monetarist argument that governments should not attempt to micromanage the economy, rather the economy will self-regulate and return to the long-run state.

The rise and fall of the monetarists

“The rapid inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s turned the nation’s attention away from the main concern of Keynesianism – unemployment – to the concern of Fisher and Friedman – inflation.” According to Brue and Grant in their book, The Evolution of Economic Thought [2012], this moment in history led to a major break with Keynesianism as monetarism rose to the fore. To many policy makers it seemed that monetarists had the answers to the problems of inflation and slow economic growth. Leaders in both the US and the UK, namely the new Chairman of the Federal Reserve, Paul Volcker, and the then British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, put in place policies to reduce the money supply through setting targets around the money growth rate. The aim was also to reduce expectations around inflation in an attempt to reduce demands for higher wages. Interventions included raising interest rates, as well as cutting spending.

While the policies were successful in cutting inflation, they also led to deep recessions in both the US and the UK, characterised by soaring unemployment. Strict monetarist policies were ultimately abandoned by both governments. The predictability of the velocity of money, which Friedman and Schwartz had charted across nearly a century, started to fail. A breakdown in the relationship between money supply, prices, and economic growth followed. The authorities at the time cited possible reasons, including changes to financial regulations and new financial innovations. However, they also argued that monetarist theories were incredibly difficult to put into practice.

So, what became of monetarism?

As our understanding of economics has evolved, the dividing lines between different schools of economic thought have become less distinct. Despite the apparent failure of monetarist policies in the 1980s, monetarist ideas have had a profound effect on the development of economic theory and policy. For example, monetary policy remains an important tool for maintaining economic stability today. Although central banks abandoned targeting the money growth rate, inflation targeting, or setting an explicit target for inflation, has become the main policy of many central banks. The monetarist inclusion of expectations in economic theory and modelling has also been subsumed into mainstream thinking, along with other key ideas, such as the natural rate of unemployment and the long run vertical Phillips curve. Of course, the debates over the necessity and extent of government intervention still rage on.

Of course, as Brue and Grant put it, given the constant evolution of economic thought, “a final assessment of these contributions must await the scrutiny of our children and grandchildren.”

Further Monetarism reading on Perlego

Whatever Happened to Monetarism?

Keynes, the Keynesians and Monetarism

The History of Economic Thought

Recharting the History of Economic Thought

Bibliography

Brue, S and Grant, R. (2012) The Evolution of Economic Thought. Cengage Learning EMEA. https://www.perlego.com/book/801895/the-evolution-of-economic-thought-with-economic-applications-and-infotrac-2semester-printed-access-card-pdf

DeLong, J. (2000) ‘The Triumph of Monetarism?’ Journal of Economic Perspectives.https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/jep.14.1.83

Friedman, M and Schwartz, A. (2008) A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton University Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/733854/a-monetary-history-of-the-united-states-18671960-pdf

Galbraith, J. (2008) ‘The Collapse Of Monetarism and the Irrelevance of the New Monetary Consensus.’ The Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/pn_08_1.pdf

Greenlaw, S, Taylor, T and Shapiro, D. (2017) Principles of Macroeconomics for AP® Courses 2e. OpenStax. https://www.perlego.com/book/695164/principles-of-macroeconomics-for-ap-courses-2e-pdf

Kurz, H and Riemer, J. (2016) Economic Thought: A Brief History. Columbia University Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/773903/economic-thought-a-brief-history-pdf

Jahan, S and Papageorgiou, C. (2014) ‘What is Monetarism?’ IMF. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2014/03/pdf/basics.pdf

Rivot, S. (2013) Keynes and Friedman on Laissez-Faire and Planning. Routledge. https://www.perlego.com/book/715468/keynes-and-friedman-on-laissezfaire-and-planning-pdf

Vaggi, G and Groenewegen, P. (2016) A Concise History of Economic Thought. Palgrave Macmillan. https://www.perlego.com/book/3499940/a-concise-history-of-economic-thought-from-mercantilism-to-monetarism-pdf

MA, Economics (Renmin University of China)

Megan Copeland spent over 10 years living and working in one of the most interesting economies in the world, China. She has a Master’s degree in Economics and a Bachelor’s Degree in Chinese Studies. Her areas of interest include economic history and behavioural economics. She is now a writer and Chinese to English translator based in London. She would recommend students of economics to listen to the Planet Money and Freakonomics podcasts for great examples of how economic theory is applied in reality.