What is Situationist Theory?

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Date Published: 09.08.2023,

Last Updated: 23.08.2023

Share this article

Who were the Situationists?

The Situationist International (SI) was a revolutionary group, composed of members of the Letterist International, International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus, and the London Psychogeographical Association. The SI was formed in July 1957 as a response to the perceived failures of previous avant-garde movements to incite an anti-capitalist revolution. Members of the SI, often called situationists, are known for their writings on the “spectacle,” their attacks on capitalism and commodity culture, and their influence on the Paris uprisings in May 1968. Situationism combined Marxist thought with artistic movements such as Dadaism and Surrealism.

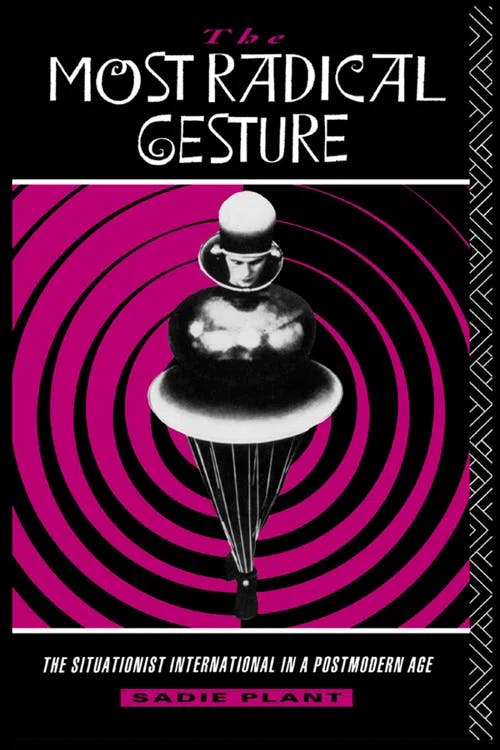

As Sadie Plant writes,

Situationist theory, the unified study of spectacular society, was therefore to be the last discipline [...], the last great project, the final push towards the transformation of everyday life from a realm of bland consumption to free creation.

Poetry, political theory, adventure, scandal: anything which disturbed the old world and revealed the possibilities of the new was collected and woven into situationist theory, and every hint of compromise with the spectacle smacked of complicity with its relations and promised certain defeat. (2002)

Sadie Plant

Situationist theory, the unified study of spectacular society, was therefore to be the last discipline [...], the last great project, the final push towards the transformation of everyday life from a realm of bland consumption to free creation.

Poetry, political theory, adventure, scandal: anything which disturbed the old world and revealed the possibilities of the new was collected and woven into situationist theory, and every hint of compromise with the spectacle smacked of complicity with its relations and promised certain defeat. (2002)

The SI believed that revolution could be achieved through the construction of “situations.” To explore what the situationists meant, we must turn to the group’s founding text, “The Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action.” The report was published by Guy Debord and details the principles and aims of the SI:

Our central purpose is the construction of situations, i.e. the concrete construction of temporary settings of life and their transformation into a higher passionate nature. We must develop an intervention, directed by the complicated factors of two great components in perpetual interaction: the material setting of life and the behaviors that it incites and that overturn it. (Debord, in The Situationists and the City, 2020)

Edited by Tom McDonough

Our central purpose is the construction of situations, i.e. the concrete construction of temporary settings of life and their transformation into a higher passionate nature. We must develop an intervention, directed by the complicated factors of two great components in perpetual interaction: the material setting of life and the behaviors that it incites and that overturn it. (Debord, in The Situationists and the City, 2020)

The definition of a situation is elaborated upon in the first issue of the Situationist International Journal (1958): “a moment of life, concretely and deliberately constructed by the collective organisation of a unitary environment and a game of events.” The situationists aimed to create events that disrupted the monotony of everyday life under capitalism, to create a revolutionary spark. As Frances Stracey writes,

[The SI] proposed a search for revolutionary forms that would be collective, creative events, in which life would be lived differently from its banalization, and it examines the failures and ensuing lessons of previous avant-gardes that aimed to change the world, not just its art, such as Futurism, Dadaism, Surrealism, CoBrA [...], Lettrism and the theatre of Brecht. (2014)

Frances Stracey

[The SI] proposed a search for revolutionary forms that would be collective, creative events, in which life would be lived differently from its banalization, and it examines the failures and ensuing lessons of previous avant-gardes that aimed to change the world, not just its art, such as Futurism, Dadaism, Surrealism, CoBrA [...], Lettrism and the theatre of Brecht. (2014)

Examples of situations include graffiti, protests, and riots. Stracey adds,

Any techniques or technologies might be tactically deployed. And constructed situations should be anti-hierarchical, non- or trans-disciplinary, amateurish or non-specialized, itinerant, ephemeral and, most importantly, collectively prepared and developed. (2014)

Guy Debord

Guy Debord was a prominent figure in the SI, developing some of its most well-known theories. Though Debord wrote on a variety of issues whilst a member of the SI, his main contributions are his development of psychogeography (and the theory of dérive) and his writings on the spectacle.

Psychogeography

First theorized by the letterists, psychogeography was later developed by Debord in “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography” (1955). Debord defines “psychogeography” as

the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals. (Debord, in The Situationists and the City, 2020)

In other words, psychogeography is the study of how a specific environment impacts an individual’s emotions and behavior. An environment may include spatial organization, architecture, activities occurring within it, and so on. Debord proposed that, in order to truly understand how the city produces our responses, we must take part in a practice he calls “dérive.” During a dérive, a walker strolls with no specific destination or route in mind, paying attention to why they choose specific paths and what emotions they feel when walking through different spaces. For example, a pedestrian will, most likely, follow footpaths, not step over railings or barriers, and avoid unlit alleys. Psychogeography makes us pause and question how we engage with the city, why barriers have been placed in certain locations, and to what extent the city has become hostile towards pedestrians.

Debord suggests that the act of dérive, and psychogeography more broadly, is essential in freeing the public from the everyday monotony brought about by capitalism. He writes,

[...] the application of this will to ludic creation must be extended to all known forms of human relationships, and must for example influence the historical evolution of emotions like friendship and love. Everything leads to the belief that the main insight of our research lies around the hypothesis of constructions of situations. A human being’s life is a sequence of chance situations, and if none of them is exactly similar to another, at the least these situations are, in their immense majority, so undifferentiated and so dull that they perfectly present the impression of similitude. (“Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” in The Situationists and the City, 2020)

For more information, see our study guide “What is Psychogeography?”

The spectacle

The spectacle is the most influential concept introduced by a member of the SI. In The Society of the Spectacle (1967), Debord argues that life under consumer capital has become a society of the spectacle — that is, a society in which image over authentic reality prevails. Debord writes,

The whole life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. All that once was directly lived has become mere representation. (1967, [2020])

Guy Debord

The whole life of those societies in which modern conditions of production prevail presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. All that once was directly lived has become mere representation. (1967, [2020])

Let’s take celebrity culture as a prominent example: a celebrity is created by a series of images; in essence, they become a brand to be emulated by the public, a representation of an ideal rather than a real person. Dissatisfied with taking over the realm of celebrity and popular culture, the spectacle has infiltrated every aspect of our society. Public figures and ordinary citizens are bombarded with representative images to the extent that they are unable to live an authentic life under capitalism.

The notion of the spectacle informs many situationist writings, whether they be related to art, anti-capitalism, or revolution. As such, it is important to keep in mind this definition, as the spectacle will appear throughout this guide.

For more information, see our study guide “What is Guy Debord’s Theory of the Spectacle?”

Détournement

The situationists believed that art needed to be politically motivated and, as such, they rejected all other art movements which produced new forms of art. They argued that producing new forms of art was simply creating new commodities, rather than resisting capitalism. Debord calls works of art “short-lived artificial constructs speaking the official language of the state” (1967, [2020]). However, the SI acknowledged the potential value of art to separate itself from its commodity status, a separation achieved through détournement. Détournement is the artistic practice of taking existing artworks, ideas, or symbols, and repurposing, manipulating, or otherwise transforming them to subvert their meaning.

Détournement was originally a practice of the letterists, later adopted by the situationists. As Anja Kanngieser notes in Experimental Politics and the Making of Worlds (2016), the letterists had most famously used methods of détournement in their hijacking of the Notre Dame Cathedral on Easter Sunday in 1950. To critique the Catholic Church,

[a] former Dominican theologian, Michel Mourre, clothed in his monk’s cloak and surrounded by his co-conspirators, took to the pulpit during a pause in the High Easter Mass and began to preach on the death of god. (Kanngieser, 2016)

Anja Kanngieser

[a] former Dominican theologian, Michel Mourre, clothed in his monk’s cloak and surrounded by his co-conspirators, took to the pulpit during a pause in the High Easter Mass and began to preach on the death of god. (Kanngieser, 2016)

In this mock sermon, Mourre accused the Church of swindling money. After the demonstration, the group was arrested for disrupting the televised mass. This protest contributed to the formation of the SI. Kanngieser adds that “even early on, the reach of such détourned forms were not to be underestimated and they attained an almost cultlike status” (2016).

In “A User’s Guide to Détournement,” published prior to the official formation of the SI, Debord and Gil J. Wolman write that the main purpose of détournement

apart from its intrinsic propaganda powers, will be the revival of a multitude of bad books [...] and above all an ease of production far surpassing in quantity, variety and quality the automatic writing that has bored us for so long. (In Situationist International Anthology, 1956, [2006])

Détournement will lead to “the discovery of new aspects of talent” and would disrupt “social and legal conventions,” making it a “powerful cultural weapon in the service of a real class struggle” (Debord and Gilman, 1956, [2006]). The essay delineates three forms of détournement: minor, deceptive, and extensive.

- Minor détournement refers to the détournement of an artistic work that is not symbolic in and of itself and only gains meaning when placed in a new context, such as a press clipping or a seemingly innocuous photograph.

- Deceptive détournement is the détournement of “an intrinsically significant element, which derives a new scope from a different context,” such as a political slogan transformed to take on new meanings (Debord and Gilman, 1956, [2006]).

- Extensive détournement is a combination of these previous two forms.

As McKenzie Wark writes,

Détournement sifts through the material remnants of past and present culture for materials whose untimeliness can be utilized against bourgeois culture. But rather than further elaborate modern poetics, Détournement exploits it. The aim is the destruction of all forms of middle-class cultural shopkeeping. As capital spreads outwards, making the world over in its image, at home it finds its own image turns against it. (2015)

McKenzie Wark

Détournement sifts through the material remnants of past and present culture for materials whose untimeliness can be utilized against bourgeois culture. But rather than further elaborate modern poetics, Détournement exploits it. The aim is the destruction of all forms of middle-class cultural shopkeeping. As capital spreads outwards, making the world over in its image, at home it finds its own image turns against it. (2015)

In détournment, we can clearly see the influence of the Dada art movement, which took everyday objects and re-positioned them as “modern art” to mock the institution of art. An example is “L.H.O.O.Q” (1919) by Marcel Duchamp: the artist took a postcard of Leonardo Di Vinci’s Mona Lisa (c. 1503–1519) and drew on a mustache. These works of art made from mass-produced objects were known as “readymades.”

For further information on Dadaism, see our study guide “What is Dadaism? Understanding the Dada Art Movement.”

Détournement, like Dada art, reappropriated symbols and iconic artistic paintings to critique capitalism and commodity culture. For example, the situationist painter Asger Jorn engaged in the rebellious act of repurposing art. In 1959, Jorn created his Modification series, which consisted of modified paintings Jorn had purchased from flea markets. An example of his work includes Ainsi s’Ensor (Out of this World – after Ensor), 1962) in which he paints over the face of the hanged man in the original scene with that of a clown, making for a grotesque image.

In an essay accompanying the exhibit entitled “Détourned Painting,” Jorn comments on how art has been made digestible for the consumer. He writes,

Be modern,

collectors, museums.

If you have old paintings,

do not despair.

Retain your memories

but détourn them

so that they correspond with your era.

Why reject the old

if one can modernize it

with a few strokes of the brush?

This casts a bit of contemporaneity

on your old culture.

Be up to date,

and distinguished

at the same time.

Painting is over.

You might as well finish it off.

Détourn.

Long live painting.

(Jorn, quoted by Kenneth Goldsmith in Uncreative Writing, 2011)

Kenneth Goldsmith

Be modern,

collectors, museums.

If you have old paintings,

do not despair.

Retain your memories

but détourn them

so that they correspond with your era.

Why reject the old

if one can modernize it

with a few strokes of the brush?

This casts a bit of contemporaneity

on your old culture.

Be up to date,

and distinguished

at the same time.

Painting is over.

You might as well finish it off.

Détourn.

Long live painting.

(Jorn, quoted by Kenneth Goldsmith in Uncreative Writing, 2011)

The practice of détournement would later become part of the Paris uprisings, predominantly in the form of graffiti; this was known as “ultra-détournement” and will be explored later in this guide.

Anti-capitalist revolution

Just months before the Paris uprisings, Raoul Vaneigem published The Revolution of Everyday Life (1967). It remains one of the most influential works produced by the SI , alongside Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle. Vaneigem’s aim was to demonstrate how capitalism (and alienation as a result of capitalism) impacts the everyday lives of the population. Vaneigem writes,

Anyone who talks about revolution and class struggle without referring explicitly to everyday life—without grasping what is subversive about love and positive in the refusal of constraints—has a corpse in his mouth. (1967, [2012])

Raoul Vaneigem

Anyone who talks about revolution and class struggle without referring explicitly to everyday life—without grasping what is subversive about love and positive in the refusal of constraints—has a corpse in his mouth. (1967, [2012])

Vaneigem explains that,

Modern comforts seemed at first to promise everyone a life richer even than the dolce vita of the feudal aristocracy. But in fact they turned out to be mere offshoots of capitalist productivity, offshoots doomed to premature old age as soon as the distribution system transformed them into nothing but objects of passive consumption. Working to survive, surviving by consuming and for the sake of consuming: the hellish cycle is complete. (1967, [2012])

Vaneigem takes inspiration from Marx by exploring how capitalism subsumes both the individual’s working hours and leisure time. As capitalism produces an abundance of commodities and the spectacle creates false needs, workers are motivated to spend the majority of their lives working, in order to mindlessly consume the endless commodities available to them.

Enslavement to capitalism is further discussed by Debord:

The spectacle subjects living human beings to its will to the extent that the economy has brought them under its sway. For the spectacle is simply the economic realm developing for itself – at once a faithful mirror held up to the production of things and a distorting objectification of the producers. (1967, [2020])

As a result of this alienation, both Debord and Vaneigem advocate for revolution.

Debord explains that alienation under capitalism means that workers can no longer recognize their own exploitation. A class revolution must involve workers acknowledging their alienation and subjugation. Debord writes,

The proletarian revolution is predicated entirely on the requirement that, for the first time, theory as the understanding of human practice be recognized and directly lived by the masses [...] It is thus the very evolution of class society into the spectacular organization of non-life that obliges the revolutionary project to become visibly what it always was in essence. (1967, [2020])

Rather than recommending, as Marx does, that the proletariat seize the means of production, Debord argues that the reality of labor under capitalism must become transparent. Every member of society could then participate in a self-conscious way, no longer under the illusion of the spectacle.

Vaneigem argues that class revolt will occur when poverty, and the resulting starvation, illness, and isolation it brings, demystifies capitalism. Vaneigem writes,

It is the whole world of hierarchical power, of the State, of sacrifice, of exchange, of the quantitative—the commodity as will and representation of the world—that is now coming under attack from the driving forces of an entirely new society, a society still to be invented yet already with us. (1967, [2012])

In this new world order, there are several issues Vaneigem argues need to be addressed, including replacing the capitalist system of labor and exchange; “the dethronement of the value of money”; “the reconstruction of human relations”; the implementing of positive laws designed to encourage freedom; and the organization of the movement itself (1967, [2012]). Vaneigem further notes that in order to create this new society, members of the SI must respect equality and not slip into authoritarianism.

Without a concrete plan in mind, Vaneigem remains optimistic about the group’s ability to incite revolution and create a new world. Vaneigem writes,

The Situationists do not come with some plan in hand for a new kind of society; they do not say ‘Here is the ideal form of social organization. All hail!’ They merely show, by fighting for themselves and maintaining the highest possible consciousness of that struggle, why people really fight and why becoming conscious of the fight is paramount. (1967, [2012])

The Paris uprisings

The ideologies of the situationists became less theoretical and played an active role in the Paris uprisings of May 1968, initially a student protest against underfunded universities and Western capitalism. The students were joined by striking workers across France who were protesting exploitative labor and poor wages. During this period of unrest, anti-capitalist and anti-establishment graffiti appeared throughout Paris. Situationist slogans responding to the protest were inscribed on walls across the city and included:

- “Never work.”

- “The commodity is the opium of the people.”

- “The more you consume, the less you live.”

Debord had previously graffitied “Never work” on the Rue de Seine in 1953; this slogan would later accompany four others at the SI gallery exhibit in Denmark in 1963 as part of a Debord’s series “Directives.” For this exhibition, he displayed artwork that simply featured slogans to be repurposed by others as graffiti. Stracey explains that this was,

an attempt to escape the limiting conditions of the gallery space, which repressed the interaction of these slogans with their social environment through its ‘do not touch’ policy. (2014)

While only a handful of members of the SI were still operating in Paris in 1968 (Debord, Vaneigem, René Viénet, and Mustapha Khayati), they became involved in the protests and created the “Situationist International Enragés Committee” with the Enragés, an anarchist group. As Anna Trespeuch-Berthelot writes,

Strengthened by this democratic legitimacy, the committee increased its external communications: diffusing tracts, détourné comics, slogans through loudspeakers and on the walls of the Sorbonne and, perhaps most audacious of all, Détournements that defaced the oil paintings that hung on the walls of the venerable old lecture halls. (Trespeuch-Berthelot, “The Shadow Cast by the Situationist International on May ’68,” in The Situationist International, 2020)

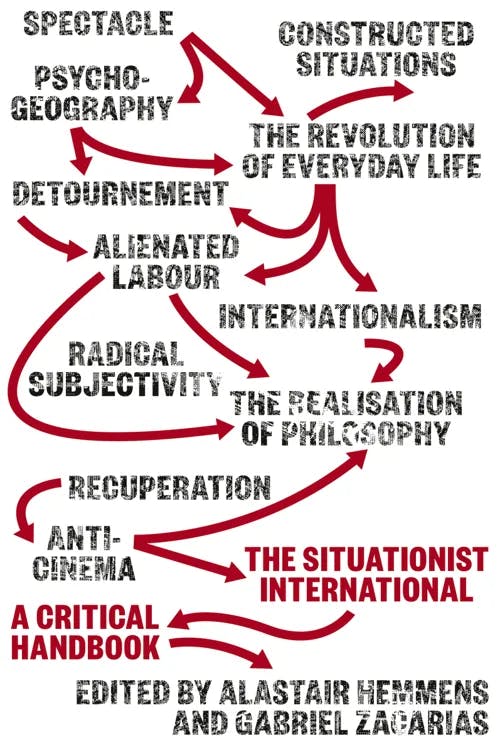

Edited by Alastair Hemmens and Gabriel Zacarias

Strengthened by this democratic legitimacy, the committee increased its external communications: diffusing tracts, détourné comics, slogans through loudspeakers and on the walls of the Sorbonne and, perhaps most audacious of all, Détournements that defaced the oil paintings that hung on the walls of the venerable old lecture halls. (Trespeuch-Berthelot, “The Shadow Cast by the Situationist International on May ’68,” in The Situationist International, 2020)

In July 1968, Viénet published Enragés et Situationnistes dans le Mouvement des Occupations, which combined written testimony about the riots, newspaper photographs, posters, comic strips, and, perhaps most significantly, détourned photographs of graffitied walls. Featuring graffiti marked both its significance for the protestors and for SI more broadly:

Damage was a sign of, and site for, the possibility of reconstruction, proof that no situation is eternally given or fixed, but, on the contrary, historically contingent, impermanent, fallible and mutable. This suited the Situationists’ entire programme of constructing situations, which was essentially transitory. (Stracey, 2014)

Graffiti was ultra-détournement’s most prevalent form as it would be seen by numerous citizens.

The legacy of Situationist International

The Situationist International disbanded in 1972, though many prominent members still continued their work. The main goal of the situationists, to begin an anti-capitalist revolution that would empower a new generation of self-conscious workers and consumers, has been regarded by many as a failure. As Plant writes,

Neither have there been any further projects of the scale of that perpetrated by the SI and, in the present fin de millénium atmosphere of postmodernity, such all-encompassing revolutionary theories are said to be no longer possible. They bear the illegitimate arrogance of political totalitarianism, depending on unsupportable beliefs and assuming the possibility of ascertaining the way the world really is, regardless of the vicissitudes of appearance or the ambiguities of meaning. (2002)

Sadie Plant

Neither have there been any further projects of the scale of that perpetrated by the SI and, in the present fin de millénium atmosphere of postmodernity, such all-encompassing revolutionary theories are said to be no longer possible. They bear the illegitimate arrogance of political totalitarianism, depending on unsupportable beliefs and assuming the possibility of ascertaining the way the world really is, regardless of the vicissitudes of appearance or the ambiguities of meaning. (2002)

Despite this criticism, Plant acknowledges the impact of the situationists on contemporary critical theory:

But in spite of the radical opposition of situationist and postmodern thought, all theoretisations of postmodernity are underwritten by situationist theory and the social and cultural agitations in which it is placed. The situationist spectacle prefigures contemporary notions of hyperreality, and the world of uncertainty and superficiality described and celebrated by the postmodernists is precisely that which the situationists first subjected to passionate criticism. (2002)

To this extent, the situationist agenda has been successful: through these postmodern theories, many now critique the mysticism of capitalism. Whether this has been sufficient in enacting tangible change, is another debate altogether.

We can further see the legacy of the Sl in art which seeks to challenge the status quo and the nature of capitalism. Today, we see détournement take the form of “culture jamming,” in which fake adverts, hoax news reports, or adapted company logos are used to critique that particular brand, company, or the power of the media. An example of this would be the transformation of the Burger King logo to say “Murder King,” created and prominently displayed by the animal rights group PETA.

However, attempts at détournement have since been appropriated by the brands that these counter-cultural movements have critiqued. A recent example appears in the Black Mirror episode “Joan is Awful” (2023), in which the platform Streamberry uses computer-generated images of celebrities to produce new content for their platform. The episode appropriates Netflix’s logo in its attempted critique of streaming services, but its criticism is undermined by the fact that this episode is streamed on Netflix. After all, all publicity is good publicity.

Regardless of the spectacular society’s ability to commodify all forms of art, including those actively critiquing it, the public’s mere awareness of this tactic partially fulfills Debord’s revolutionary agenda. Due to the ease of content creation, media is, in a sense, handed back to the masses. We have the tools now to condemn poor business practices, to speak out about our own alienation at work, and to try and incite change. For example, YouTubers and TikTokers expose the reality of fast fashion by sharing their research online. These creators can recognize and condemn the monotonous products that company’s sell and demand better practices and products. Though we are far from the new society that Vaneigem and Debord envisioned, our access to information has continued to increase in the twenty-first century and with it our ability to destabilize the myth of the spectacular society.

Further reading on Perlego

The Situationist International in Britain: Modernism, Surrealism, and the Avant-Garde (2016) by Sam Cooper

Comments on the Society of the Spectacle (2020) by Guy Debord

A Letter to My Children and the Children of the World to Come (2019) by Raoul Vaneigem

FAQs on situationist theory

What is situationist theory in simple terms?

What is situationist theory in simple terms?

What is an example of a situation?

What is an example of a situation?

What is the spectacle?

What is the spectacle?

Who were the main members of Situationist International?

Who were the main members of Situationist International?

What is détournement?

What is détournement?

Bibliography

Black Mirror: “Joan is Awful” (2023) Directed by Ally Pankiw. Available on Netflix.

Cooper, S. (2016) The Situationist International in Britain: Modernism, Surrealism, and the Avant-Garde. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1635881/the-situationist-international-in-britain-modernism-surrealism-and-the-avantgarde-pdf

Craib, R., and Maxwell, B. (2015) No Gods, No Masters, No Peripheries: Global Anarchisms. PM Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2584899/no-gods-no-masters-no-peripheries-global-anarchisms-pdf

Debord, G. (2020) “Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography,” in McDonough, T. (ed.) The Situationists and the City: A Reader. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3785848/the-situationists-and-the-city-a-reader-pdf

Debord, G. (2020) “The Report on the Construction of Situations and on the International Situationist Tendency’s Conditions of Organization and Action,” in McDonough, T. (ed.) The Situationists and the City: A Reader. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3785848/the-situationists-and-the-city-a-reader-pdf

Debord, G. (2020) The Society of the Spectacle. Translated by D. Nicholson-Smith. Zone Books. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1636424/the-society-of-the-spectacle-pdf

Debord, G., and Wolman, C. J. (2006) “The User’s Guide to Détournement,” in Knabb, K. (ed) Situationist International Anthology. Bureau of Public Secrets. Available at: https://www.akpress.org/situationistinternationalanthology.html

Goldsmith, K. (2011) Uncreative Writing. Columbia University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/661987/uncreative-writing-pdf

Hemmens, A., and Zacarias, G. (eds.) (2012) The Situationist International: A Critical Handbook. Pluto Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1419996/the-situationist-international-a-critical-handbook-pdf

Kanngieser, A. (2016) Experimental Politics and the Making of Worlds. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1630471/experimental-politics-and-the-making-of-worlds-pdf

McDonough, T. (ed.) (2020) The Situationists and the City: A Reader. Verso. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3785848/the-situationists-and-the-city-a-reader-pdf

Meecham, P., and Arnold, D. (eds.) (2017) A Companion to Modern Art. Wiley-Blackwell. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/993577/a-companion-to-modern-art-pdf

Plant, S. (2002) The Most Radical Gesture: The Situationist International in a Postmodern Age. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1618114/the-most-radical-gesture-the-situationist-international-in-a-postmodern-age-pdf

Shield, P. (2018) Comparative Vandalism: Asger Jorn and the Artistic Attitude to Life. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1480187/comparative-vandalism-asger-jorn-and-the-artistic-attitude-to-life-pdf

Stracey, F. (2014) Constructed Situations: A New History of the Situationist International. Pluto Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/664432/constructed-situations-a-new-history-of-the-situationist-international-pdf

Trespeuch-Berthelot, A. (2012) “The Shadow Cast by the Situationist International on May ’68,” in Hemmens, A. and Zacarias, G. (eds.) The Situationist International: A Critical Handbook. Pluto Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1419996/the-situationist-international-a-critical-handbook-pdf

Vaneigem, R. (2012) The Revolution of Everyday Life. Translated by D.Nicholson-Smith. PM Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2584951/the-revolution-of-everyday-life-pdf

René Viénet (1992) Enragés et Situationnistes dans le Mouvement des Occupations. Rebel Press. Available at: https://www.worldcat.org/title/55553452

Wark, M. (2015) The Beach Beneath the Street: The Everyday Life and Glorious Times of the Situationist International. Verso. Available at:

https://www.perlego.com/book/731081/the-beach-beneath-the-street-the-everyday-life-and-glorious-times-of-the-situationist-international-pdf

PhD, English Literature (Lancaster University)

Sophie Raine has a PhD from Lancaster University. Her work focuses on penny dreadfuls and urban spaces. Her previous publications have been featured in VPFA (2019; 2022) and the Palgrave Handbook for Steam Age Gothic (2021) and her co-edited collection Penny Dreadfuls and the Gothic was released in 2023 with University of Wales Press.