What is the Harrod-Domar Model?

MA, Management Science (University College London)

Date Published: 30.08.2024,

Last Updated: 30.08.2024

Share this article

Definition and origins

The Harrod-Domar model aims to explain the rate at which economies are growing and will continue to grow in the future. The model was co-created by economists Sir Roy Harrod and Evsey Domar in the 1930s and 1940s at a time when issues surrounding economic growth were particularly relevant in the aftermath of the Great Depression and World War II.

In an economic timeline (Figure 1), the Harrod-Domar model belongs to the development economics era within the broader waves of economic thought. To learn more about development economics as a wave of economic thought, see Essentials of Development Economics (J. Edward Taylor and Travis J. Lybbert, 2020) or Development Economics: A Critical Introduction (Shahrukh Rafi Khan, 2019).

Fig. 1. Waves of economic thought timeline

As shown in the timeline, there is an overlap between development economics and Keynesian economics, suggesting that both theories might be intertwined and influenced by one another. Although this cannot necessarily be said for all theories developed in both eras, it is indeed the case for the Harrod-Domar model as explained in the book Mainstream Growth Economists and Capital Theorists:

Both Harrod and Domar were, in some sense, partisans of the Keynesian revolution and, naturally, incorporated many special Keynesian features in their models [...]. (Marin Muzhani, 2014)

Marin Muzhani

Both Harrod and Domar were, in some sense, partisans of the Keynesian revolution and, naturally, incorporated many special Keynesian features in their models [...]. (Marin Muzhani, 2014)

Keynesian economists believed that savings and investment are closely linked to economic growth. These are key elements that, as we’ll explore throughout this guide, are central to the Harrod-Domar model.

What sets the Harrod-Domar model apart is that it argues that savings and capital investment are the two main and only levers driving economic growth. In Development Economics, Debraj Ray explains why, in the eyes of the Harrod-Domar model, saving and investment are important:

Economic growth is positive when investment exceeds the amount necessary to replace depreciated capital, thereby allowing the next period’s cycle to recur on a larger scale. The economy expands in this case; otherwise it is stagnant or even shrinks. This is why the volume of savings and investment is an important determinant of the growth rate of an economy. (1998)

Debraj Ray

Economic growth is positive when investment exceeds the amount necessary to replace depreciated capital, thereby allowing the next period’s cycle to recur on a larger scale. The economy expands in this case; otherwise it is stagnant or even shrinks. This is why the volume of savings and investment is an important determinant of the growth rate of an economy. (1998)

Essentially, the Harrod-Domar model argues that saving and capital investment are the two main variables that should be modeled in order to determine the growth trajectory of an economy.

This study guide provides a detailed overview of the workings of the Harrod-Domar model, describing its key assumptions and mathematical workings, including examples. It also examines real-world applications of the model, followed by a discussion of the most common criticisms and subsequent advancements that have helped further develop this area of economic theory.

How the Harrod-Domar model works

Key assumptions

To understand the technical workings of the Harrod-Domar model, let us first consider the five key assumptions which underpin the theory. These are clearly stated in Development Economics: Theory and Practice:

1. The economy is closed to trade and foreign direct investment (FDI). Hence all investment has to come from domestic savings.

2. Capital and labor are used in fixed proportions in production. Hence there are no substitution possibilities among inputs.

3. Capital is the limiting factor to output growth, not labor. Labor is in unlimited supply. Hence population growth and labor availability are not issues.

4. There are constant returns to scale for each factor. Hence the return to capital at the margin is always the same, whatever the level of the stock of capital.

5. Technology is such that a fixed quantity of additional capital (ΔK) gives us a fixed proportional increase in output (ΔY), where the proportionality factor is k = ΔK/ΔY = ICOR, or the incremental capital output ratio, an assumed simple technological specification. (Alain de Janvry and Elisabeth Sadoulet, 2021)

Alain de Janvry and Elisabeth Sadoulet

1. The economy is closed to trade and foreign direct investment (FDI). Hence all investment has to come from domestic savings.

2. Capital and labor are used in fixed proportions in production. Hence there are no substitution possibilities among inputs.

3. Capital is the limiting factor to output growth, not labor. Labor is in unlimited supply. Hence population growth and labor availability are not issues.

4. There are constant returns to scale for each factor. Hence the return to capital at the margin is always the same, whatever the level of the stock of capital.

5. Technology is such that a fixed quantity of additional capital (ΔK) gives us a fixed proportional increase in output (ΔY), where the proportionality factor is k = ΔK/ΔY = ICOR, or the incremental capital output ratio, an assumed simple technological specification. (Alain de Janvry and Elisabeth Sadoulet, 2021)

These five assumptions can be summarized into the following key ideas:

- The model assumes there is no international trade meaning that any savings will happen domestically, within an individual economy.

- Capital (i.e., assets that have monetary value, such as machinery, equipment, real estate, and inventory) is the lever to growth, not labor.

- Returns from capital or technology are constant, and economic output will grow at a directly proportional rate relative to technology investment.

These assumptions are important to consider throughout the guide, as they not only make up the foundation of the theory but also open the door to potential criticisms, which we will later address.

Structural form

After outlining the model’s assumptions, de Janvry and Sadoulet move on to explaining that the Harrod-Domar model is made up of three key building blocks:

1. An aggregate production function Y: ΔY = (1/k)ΔK, obtained from the definition of the ICOR.

2. A savings function: S = sY, where S is aggregate savings and s is the rate of savings out of national income Y.

3. An investment function, where investment (I) is equal to available savings (S) and investment increases the stock of capital (ΔK): I ≡ ΔK = S. (2021)

Fig. 4. Incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR or ‘k’ in the model) formula

In essence, the Harrod-Domar model is made up of three components: Economic growth (Y) commonly referred to as output, savings (S), and the incremental capital-output ratio (k). When we put these three components together, we obtain the equation that defines the Harrod-Domar model. This is: Y= S / k

As you can see from Figure 2, the equation shows that economic growth (Y) is driven by the rate of savings (S) and the efficiency with which capital is used (k). The equation essentially tells us that higher savings and more efficient use of capital lead to faster economic growth.

Fig 2. Harrod-Domar model formula

Figure 3 below illustrates the dynamics of the Harrod-Domar model. In other words, what happens to economic growth if savings (S) and the capital-output ratio (k) increase or decrease?

Fig 3. Impact of changes in savings (S) and the capital-output ratio (k) on economic growth (Y)

Note that there is a crucial component of this equation that requires further clarification to fully grasp the Harrod-Domar model: The denominator (k), known as the incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR), represents the amount of capital (K) needed to produce an additional unit of output (Y) in an economy. This is why, as explained by de Janvry and Sadoulet, the incremental capital-output ratio (k) is defined as k =ΔK/ΔY, where ΔK is the additional capital invested in the economy, and ΔY is the corresponding increase in output generated by that capital (see Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR or ‘k’ in the model) formula

This concept requires further clarification because it is often misunderstood. A common misconception is to think of k as the absolute financial value of the capital invested in an economy (e.g., £10 billion investment in machinery). However, the incremental capital-output ratio is not an absolute monetary value; rather, it is a number that represents the efficiency with which capital is used to produce additional output.

In the Harrod-Domar equation, the different components (S, k, and Y) are interconnected. The rationale is that if people save a larger proportion of their income (S), there is more money available for investment. This new money available is likely going to be invested in capital (K), which will allow the economy to grow (Y).

The reader may wonder how Harrod and Domar arrived at this mathematical conclusion. The details can be intricate, but the short, simplified answer is that a series of fundamental identities and principles, derived from the model's assumptions, logically lead to this outcome. This chain of reasoning is thoroughly explained in Harrod’s and Domar’s works Towards a Dynamic Economics (Harrod, 1948) and Essays in the Theory of Economic Growth (Domar, 1957). (For those interested in a deeper exploration of the mathematical reasoning, Chapter 8 of Development Economics: Theory and Practice provides a detailed analysis.)

The Harrod-Domar model in practice

To illustrate the Harrod-Domar model in action, let’s use a fictional example. Say that the World Bank (a financial body that keeps track of global financial indicators, amongst other roles) has calculated, based on historical data, that in Country X, on average, an additional £10 billion investment in machinery (ΔK) leads to an increase in the economy’s output of £5 billion (ΔY). In this case, the incremental capital-output ratio (k) is £10 billion / £5 billion = 2. In other words, this means that for every £2 of capital invested (K), economic growth (Y) increases by £1. Note that, the higher the incremental capital-output ratio, the less productive the capital is; that is, more capital is needed to produce an additional unit of output.

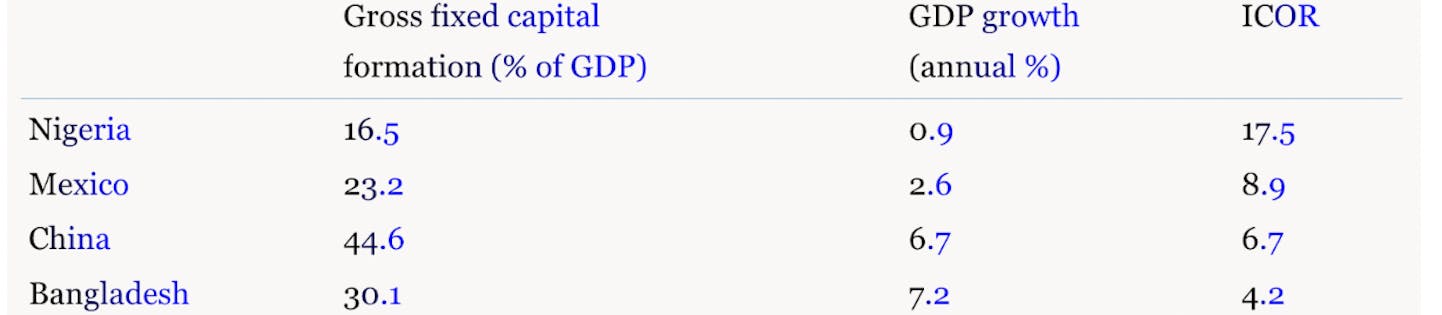

We can see an example of this in Development Economics: Theory and Practice with real data from several countries between 2015-2018 (see Figure 5).

Fig. 5. de Janvry, A. and Sadoulet, E. (2021) “Growth according to the Harrod–Domar model, 2015–2018,” in Development Economics.

As de Janvry and Sadoulet explain,

[This table] gives the ICOR for Nigeria, Mexico, China, and Bangladesh for the period 2015–2018 using this formula. They show that Nigeria and Mexico used lower productivity technology, with ICORs of 17.5 and 8.9, respectively, compared to China and Bangladesh that used more productive technology with ICORs of 6.7 and 4.2, respectively. This means, ultimately, that Nigeria needed about four times as much additional capital per unit of additional GDP as Bangladesh did. (2021)

So far, we have calculated one of the components of the Harrod-Domar model in our fictional example: the incremental capital-output ratio (k). The remaining two components (savings (S) and economic growth (Y)) are easier to calculate. Let’s suppose that the average saving rate of Country X is 10%. That is, individuals on average save 10% of their income. The growth rate (Y) of Country X according to Harrod-Domar’s model would be 5%, calculated using the formula Y = S / k, where S = 10% and k = 2. The model suggests that Country X is expected to grow at a rate of 5% per year. This is a direct result of the country's savings rate (10%) and the efficiency with which it converts capital into output (capital-output ratio of 2).

A real-life application of the Harrod-Domar model

Often, economic models can be interesting from an academic standpoint, but appear difficult to translate to real life and its applications. This section aims to bring the model to life and highlight a specific situation in economic history where the Harrod-Domar model proved useful.

It is fascinating to see how a simple calculation can be used to influence economic policy and write economic history. Indeed, as explained in “Aid in the Development Process” (1986) written by Anne O. Krueger, Chief Economist at the World Bank between 1982 and 1986, the Harrod-Domar model was one of the two academic underpinnings that informed the creation of the Marshall Plan. For those unfamiliar with this term – also known as the European Recovery Program – the Marshall Plan was a US governmental intervention whereby financial aid in the form of capital investment was provided to Western European countries after World War II to encourage their economic recovery.

The plan was proposed by the US Secretary of State, George C. Marshall, in a speech at Harvard University in 1947. An overview of the Marshall Plan and its benefits is provided in The Marshall Plan:

Marshall would formally propose the ERP at Harvard a week later. Between 1948 and 1952, the program made the United States the principal benefactor of Europe’s post-World War Two recovery. During this four– year period, grants and loans totaling close to 13 billion dollars flowed across the Atlantic in the form of goods, development projects, and other assistance programs. It would play a vital role in addressing the difficulties Washington’s Western European partners faced as they dug out from the destruction of Adolf Hitler’s six-year onslaught. Great Britain, Ireland, France, Italy, the Tri-zone (the later Federal Republic of Germany), Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Portugal, Greece, Turkey, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, Austria, and Switzerland—16 nations in all—benefited from American aid to help cement what Marshall, in his 12-minute Harvard address, called “the rehabilitation of the economic structure of Europe.” (Michael Holm, 2016)

Michael Holm

Marshall would formally propose the ERP at Harvard a week later. Between 1948 and 1952, the program made the United States the principal benefactor of Europe’s post-World War Two recovery. During this four– year period, grants and loans totaling close to 13 billion dollars flowed across the Atlantic in the form of goods, development projects, and other assistance programs. It would play a vital role in addressing the difficulties Washington’s Western European partners faced as they dug out from the destruction of Adolf Hitler’s six-year onslaught. Great Britain, Ireland, France, Italy, the Tri-zone (the later Federal Republic of Germany), Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Portugal, Greece, Turkey, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, Austria, and Switzerland—16 nations in all—benefited from American aid to help cement what Marshall, in his 12-minute Harvard address, called “the rehabilitation of the economic structure of Europe.” (Michael Holm, 2016)

This real-life application underscores the significance of the Harrod-Domar model in shaping economic policy. By providing a clear framework for understanding the relationship between savings, capital investment, and economic growth, the model has managed to influence historical economic recovery efforts and has guided policymakers in developing strategies that promote sustainable economic growth.

Criticisms of the Harrod-Domar model

As seen in the previous fictional example, the Harrod-Domar model is simple to calculate and interpret. This simplicity is one of the main things that have been criticized with regards to Harrod’s and Domar’s work, as explained in Mainstream Growth Economists and Capital Theorists:

The Harrod-Domar approach is based mainly on the rigidity of its assumptions and the simplicity of its construction. [....] Even though their purpose was to isolate and develop some of the problems concerning growing economies, their assumptions and tools were not appropriate. (Muzhani, 2014)

Marin Muzhani

The Harrod-Domar approach is based mainly on the rigidity of its assumptions and the simplicity of its construction. [....] Even though their purpose was to isolate and develop some of the problems concerning growing economies, their assumptions and tools were not appropriate. (Muzhani, 2014)

This quotation highlights that the simplicity of the Harrod-Domar model stems from the rigidity of its assumptions. Recall from earlier sections the summarized assumptions that underpin the model: 1) no international trade, 2) capital investment is the primary driver of growth, and 3) economic output increases in direct proportion to capital investment. Throughout history, it is often these assumptions in economic models that provide the basis for critique, enabling economists to identify limitations and pave the way for the development and refinement of economic theories.

Take for instance the first assumption. It is unrealistic to assume that countries will have no international trade, especially as countries and continents become increasingly globalized. A clear illustration of this is the Marshall Plan. The financial capital investment in Western European countries was sourced internationally, specifically from the United States, highlighting the significant role of cross-border economic interactions.

If we examine the second assumption, we find further grounds for reflection. One might question the role of labor in economic growth. If labor doesn’t contribute, why do individuals strive to work, and why is employment so strongly promoted economically? The book Foundations of Macroeconomics specifically addresses this aspect of the model as an area for improvement:

It is hard to believe that upward trends in per capita output are to be attributed entirely to improvements in technology and not at all to increases in the amount of capital per worker. (Frederick S. Brooman and Henry D. Jacoby, 2017)

Frederick S. Brooman and Henry D. Jacoby

It is hard to believe that upward trends in per capita output are to be attributed entirely to improvements in technology and not at all to increases in the amount of capital per worker. (Frederick S. Brooman and Henry D. Jacoby, 2017)

Lastly, let’s critically look at the final assumption: economic output increases in direct proportion to capital investment. Realistically speaking, what is ever constant in economies? We frequently see charts in the news or the press depicting microeconomic and macroeconomic variables over time, marked by significant fluctuations – peaks and troughs. This might lead the reader to question whether this assumption can realistically reflect actual growth when using the model. Chakib Bourayou and Elisa Van Waeyenberge's essay "How do Economies Grow" delves into this assumption in greater depth, acknowledging from the outset that it is indeed a "simple beginning to dynamic theory":

The Harrod-Domar model is an exercise in ‘equilibrium macro-dynamics’. It proposes a simple beginning to dynamic theory as the best way to initiate research into growth of the capitalist economy. This implies theorising growth along a steady-state balanced growth (SSBG) path. Along a steady-state growth path, all variables, including output, labour and capital, grow at a constant rate (i.e. their magnitude increases but at a constant rate). Along a balanced growth path, all variables grow at the same rate. A steady-state balanced growth path then implies a form of ‘equilibrium’ over time whereby all variables grow at constant and equal rates, i.e. the economy just gets bigger, but otherwise remains the same in all other respects. This means that proportions or ratios in the economy, like for instance the capital–output ratio (COR), remain constant. You could think of the economy along an SSBG path in terms of a specific picture that is being enlarged – without any other changes. (2020)

Edited by Kevin Deane and Elisa van Waeyenberge

The Harrod-Domar model is an exercise in ‘equilibrium macro-dynamics’. It proposes a simple beginning to dynamic theory as the best way to initiate research into growth of the capitalist economy. This implies theorising growth along a steady-state balanced growth (SSBG) path. Along a steady-state growth path, all variables, including output, labour and capital, grow at a constant rate (i.e. their magnitude increases but at a constant rate). Along a balanced growth path, all variables grow at the same rate. A steady-state balanced growth path then implies a form of ‘equilibrium’ over time whereby all variables grow at constant and equal rates, i.e. the economy just gets bigger, but otherwise remains the same in all other respects. This means that proportions or ratios in the economy, like for instance the capital–output ratio (COR), remain constant. You could think of the economy along an SSBG path in terms of a specific picture that is being enlarged – without any other changes. (2020)

So, what happens next? Economic criticisms can be viewed as constructive, driving advancements in economic theory and striving to create a more accurate representation of the world around us. Several books, including those mentioned earlier, introduce the Solow model, created by American economist Robert Solow and Trevor Swan, model as the “neo-classical response” to Harrod's and Domar's work (see Figure 1). Mark Setterfield briefly explains how the Solow model differs from and advances upon the Harrod-Domar model, offering a more nuanced approach to economic growth:

The neoclassical response, meanwhile, conceived growth and development as a supply-side process. The first generation of neoclassical models, based on the work of Solow (1956), focused on the substitution of capital for labor, and the ability of the economy to vary the capital–labor ratio until the actual, warranted and natural rates of growth are reconciled. ("Macrodynamics," A New Guide to Post-Keynesian Economics, 2001)

Edited by Richard P. F. Holt and Steven Pressman

The neoclassical response, meanwhile, conceived growth and development as a supply-side process. The first generation of neoclassical models, based on the work of Solow (1956), focused on the substitution of capital for labor, and the ability of the economy to vary the capital–labor ratio until the actual, warranted and natural rates of growth are reconciled. ("Macrodynamics," A New Guide to Post-Keynesian Economics, 2001)

Indeed, the work Solow is a great example of how an economist can develop previous economic theories. For more information on the Solow model, you can refer to The Solow Model of Economic Growth (Paweł Dykas, Tomasz Tokarski, and Rafał Wisła, 2022) or Macroeconomics (Jagdish Handa, 2010).

Closing thoughts

The Harrod-Domar model provides a clear and straightforward way to understand economic growth by focusing on the roles of savings, capital investment, and efficiency. While the model's assumptions have been subject to criticism, these very critiques have driven the evolution of economic thought, leading to more nuanced and comprehensive models like the Solow model. Ultimately, the Harrod-Domar model reminds us of the importance of continuously questioning and refining our understanding of economics, as we strive to develop theories that more accurately reflect the complexities of the real world.

Further reading on Perlego

Creating a Learning Society: A New Approach to Growth, Development, and Social Progress (2014) by Joseph E. Stiglitz et al

The Mystery of Economic Growth (2010) by Elhanan Helpman

Roy Harrod (2019) by Esteban Pérez Caldentey

Harrod-Domar model FAQs

What is the Harrod-Domar model in simple terms?

What is the Harrod-Domar model in simple terms?

What is the equation for the Harrod-Domar model?

What is the equation for the Harrod-Domar model?

How has the Harrod-Domar model been used?

How has the Harrod-Domar model been used?

What are the main criticisms of the Harrod-Domar model?

What are the main criticisms of the Harrod-Domar model?

Bibliography

Brooman, F. and Jacoby, H. D. (2017). Foundations of Macroeconomics. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1612157

Bourayou, C. and Van Waeyenberge, E. (2020) "How do Economies Grow," in Deane, K. and Waeyenberge, E. van (eds.) Recharting the History of Economic Thought. Bloomsbury Academic. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2997001

Domar, E. D. (1982) Essays in the Theory of Economic Growth. Greenwood Press.

Dykas, P., Tokarski, T., and Wisła, R. (2022). The Solow Model of Economic Growth. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3739963

Handa, J. (2010). Macroeconomics. WSPC. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/847601

Harrod, R. (1948) Towards a Dynamic Economics, some recent developments of economic theory and their application to policy. Macmillan.

Holm, M. (2016). The Marshall Plan. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1560179

Setterfield, M. (2001} “Macrodynamics” in Holt, R. and Pressman, S. (eds). A New Guide to Post-Keynesian Economics. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1601203

Khan, S. R. (2019). Development Economics. Routledge. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1573892

Krueger. A. O. (1986) “Aid in the Development Process”. World Bank. Available at: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/103741468739328050/pdf/multi-page.pdf

Muzhani, M. (2014). Mainstream Growth Economists and Capital Theorists. McGill-Queen’s University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3551341

Ray, D. (1998). Development Economics. Princeton University Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/735108

Taylor, E. and Lybbert, T. (2020). Essentials of Development Economics. University of California Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1699325

MA, Management Science (University College London)

Inés Luque has a Masters degree in Management Science from University College London. During high school, she developed a strong interest in Economics, leading her to win the national Economics prize in her country of nationality, Spain. Her expertise is in the areas of microeconomics, game theory and design of incentives. Inés is passionate about the publishing industry and is currently working in the consulting department of the Financial Times in London.