1 The new violent cartography

Introduction: “A U.S. soldier mounts guard”

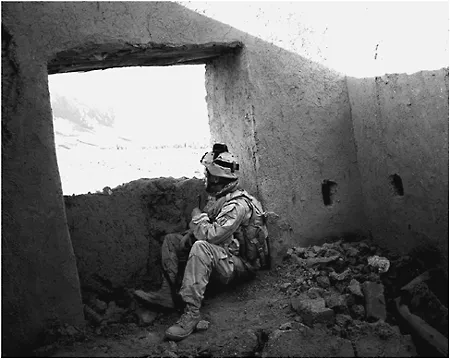

When viewed with a historical sensibility, this war photo (Figure 1.1) migrates almost irresistibly into two frames of reference. One is a history of images that juxtapose interior sanctuaries and exterior loci of danger. The other is a long trajectory of violent engagements in diverse global venues. One belongs to media history, while the other is situated in a history of inter-state hostilities. However, the two frames of reference have tended to merge since the advent of the mass-produced and disseminated image. In the case of inter-state wars, photographic and cinematic technology bring remote battle venues into view all over the globe. Accordingly, as Allen Feldman notes, while observing the media portrayals of contemporary U.S. wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the danger that “eludes everyday sensory perception becomes socially available as a cinematic structure.”1 It has become evident that the way we experience war history is inextricably linked to the forms it has taken on in media representations. Nevertheless, despite the evocative historical summonses it delivers, the photo’s accompanying description belongs to a temporal present; it references political after-effects of the United States et al.’s 2002 invasion of Afghanistan, a U.S. “policy” reaction to the 9/11 destruction of the World Trade Center:

A U.S. soldier mounts guard in a tower of the village of Mangal Khan, the main village of the Khakeran Valley, Zabul province, Afghanistan, June 27, 2005. From the U.S. and U.N. officials down to Afghan villagers, there is growing fear that this country may be at a seminal moment with three years of state-building in danger of succumbing to the barrage of violence.2

Doubtless the moment that the photographer, Tomas Munita, has captured will live on into a more pacific future, for, as Ernst Jünger’s classic observation on the role of war photography puts it, war photographs, “as instruments of a technological consciousness, preserve the image of [the] ravaged landscapes which the world of peace has long reappropriated.” And, he adds (in a remark that inspires much of the analysis in this chapter), they also speak to:

Figure 1.1 Tomas Munita’s photo of a soldier

Courtesy of AP

the life of the soldier on leave, in the reserves, and in the combat zones; the types of weaponry, the look of destruction they inflict on human beings and on the fruits of their labor, on their dwellings and on nature; the face of the battlefield at rest and at the peak of activity, as seen by the observers in the trenches or bomb craters, or from the altitude of flight—all this has been captured many times over and preserved for later ages in a fashion that complements written descriptions.3

In its present articulation, much of the semiotic urgency of the photo is owed to its composition, which is “the key,” as Munita puts it. Providing, in his terms, a “relation between the destroyed interior with the soldier hiding in it and the square luminous landscape,” the image evokes a disquieting mood: “Outside is the light of what can be a peaceful environment, but the soldier, hidden in his own dark watchtower brings a sense of terror.” Moreover, “since the tower is tilted, [it] suggest[s] imbalance, instability and obscurity.”4 In sum, in addition to conveying the emotional resonances of the particular historical moment to which Munita refers, the image evokes and preserves an instance that is part of a visually captured and thus enduring history (as Ernst Jünger famously observed5). Given Munita’s composition, the history to which this photo contributes is a history of vulnerable bodies seeking temporary refuge and a place for safe observation in hostile landscapes that seem both benign, because they are temporarily devoid of hostile engagement, and threatening, because their encompassing scale appears to thwart human attempts to manage them securely.

In what follows, I pursue the two correlated frames of reference to which I refer at the outset, first locating instances in the aesthetic patrimony of the image’s stark juxtaposition of sequestered interior and expansive exterior landscape, and then examining its related historical evocation of a changing cartography of violent encounters. With respect to this latter dimension of the image, I treat the spatial trajectories that the photograph implies, in order to map what is historically singular about the contemporary “violent cartography” that the United States’ post-9/11war on terrorism (displaced on state venues) has created.6 The most immediate spatial implication of the image is contained within it; it is the juxtaposition between the inside, a temporary sanctuary, and the immense outside that encompasses the interior. However, beyond the image’s historical immediacy—its specific reference to the conflict in Afghanistan—are its deeper historical trajectories. My turn to the image’s aesthetic patrimony, its sharp juxtaposition between interior sanctuary and exterior expanse, has a counterpart in a film history that operates most famously in a set of very similar juxtapositions in John Ford’s cinematic rendering of an earlier violent cartography.

Conceptual strategies

The two primary conceptions driving my analysis require elaboration before I treat that Ford rendering. First, what is a “violent cartography”? In my original approach to the concept, I suggested that the bases of violent cartographies are the “historically developed, socially embedded interpretations of identity and space” that constitute the frames within which enmities give rise to war-as-policy.7 Violent cartographies are thus constituted as an articulation of geographic imaginaries and antagonisms, based on models of identity–difference. Since the Treaty of Westphalia (1648), a point at which the horizontal, geopolitical world of nation-states emerged as a more salient geographic imaginary than the theologically oriented vertical world (which was imaginatively structured as a separation between divine and secular space), maps of enmity have been framed by differences in geopolitical location, and (with notable exceptions) state leaders have supplanted religious authorities. Moreover—yet also with notable exceptions—geopolitical location has since been a more significant identity marker than spiritual commitment.

During the Cold War, the coincidence between enmity and nation-state and nation-state bloc affiliation tended to coincide. And since that period, the geopolitical imaginary has been so persistent that, although the most violent contemporary enmities involve states versus networks, war-as-policy-response continues to function largely within the old geopolitical frame. Why refer to the cartographies as imaginaries? Michel Foucault supplies an ontological justification: “We must not imagine that the world turns toward us a legible face which we would have only to decipher.”8 How we receive the world (or, in Heideggerian terms, how we world) is a matter of the shape we impose on it, given the ideational commitments and institutional practices through which spatio-temporal models of identity–difference are practiced. Resistance to the geographies of enmity that drive war and security policy therefore requires one to offer “an approach to maps that provides distance from the geopolitical frames of strategic thinkers and security analysts” because, as I put it in my first approach to violent cartographies, geography is inextricably linked to “the architecture of enmity.” As a result, to understand and challenge modern security practices requires one to first map and then supply alternative imaginaries to “the security analysts way of constructing global problematics.”9 However, the mapping of a contemporary violent cartography that I provide here goes beyond geographic imaginaries. Part of that mapping involves the forces, institutions, and agencies that move bodies into the zones of violent encounter (realized, for example, in the process of military recruitment), and it involves the forces, institutions, and agencies that identify the domestic spaces where bodies are judged to be dangerous because they are associated with foreign antagonists. Necessarily, then, my analysis is deployed on both the distant and the home fronts in the United States’ pervasive war on terror, which began after 9/11, 2001.

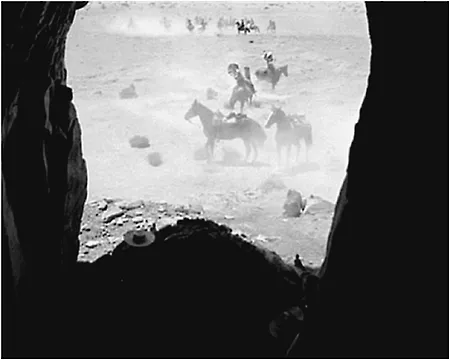

Second, to elaborate the concept of aesthetic patrimony, I want to show how the photo’s interior–exterior juxtaposition is reminiscent of several of Ford’s scenes in his treatment of the violent Euro American–Native American encounter in the West, in what is arguably his most complex and politically acute western, The Searchers (1956). An image’s “aesthetic patrimony” is the legacy of its form and implications from earlier images in similar media. To pursue that legacy is to provide a comparative frame that helps to isolate what is singular about the context of the current image. Accordingly, I am suggesting that Munita’s photo calls Ford’s film to mind because, in several scenes in The Searchers, the camera is positioned in “a place of refuge, a dark womb like space,”10 in interiors of refuge not unlike that in which Munita’s soldier is sitting. Here, I am working with two of them (Figures 1.2 and 1.3).

The opening scene of The Searchers (Figure 1.2) is both cinematically powerful and narratively expansive. It is shot from inside the cabin of Ethan Edwards’s (John Wayne) brother’s cabin, providing a view of a vast, expansive prairie, from which Edwards is approaching. Edwards, a loner who is headed west after having fought on the Confederate side in the Civil War, is part of a historical migration. He represents one type among the many kinds of bodies that flowed westward after Euro America emerged from the fratricidal conflict of the Civil War and was then free to turn its attention to another venue of violence, the one involved in the forced displacement of indigenous America. Edwards’s approach is observed by his sister-in-law from her front porch, which, architecturally, plays a role in designating the house as a refuge from outer threats. In a lyrical soliloquy by a character in an Alessandro Baricco novel, the porch is aptly described as being:

inside and outside at the same time … it represents an extended threshold. … It’s a no man’s land where the idea of protected place—which every house, by its very existence, bears witness to, in fact embodies—expands beyond its own definition and rises up again, undefended, as if to posthumously resist the claims of the open…. One could even say that the porch ceases to be a frail echo of the house it is attached to and becomes the confirmation of what the house just hints at: the ultimate sanction of the protected place, the solution of the theorem that the house merely states.11

Thus, as is the case with the scene in Afghanistan, viewed by the lone soldier, the valley and Edwards’s approach to the house cannot be discerned simply through the objects observed. One needs to recognize the historical space of observation and the ways in which the observer (Edwards’s sister-in-law) is connected to that space. Shortly after the opening shot, we are taken inside the cabin of the resident Edwards family. They are part of an earlier movement westward that established what Virginia Wexman identifies as part of an American “nationalist ideology,” the Anglo couple or “family on the land.”12 The couple (Edwards’s brother and his wife) and their children are participants in the romantic ideal of the adventurous white family, seeking to spread Euro America’s form of laboring domesticity westward in order to settle and civilize what was viewed from the East as a violent, untamed territory, containing peoples or nations unworthy of participating in an American future.

Figure 1.2 Ethan Edwards arrives

Courtesy of Warner Home Video

Figure 1.3 Ethan and Martin

Courtesy of Warner Home Video

The second image (Figure 1.3) from The Searchers participates in a referential montage. It reproduces and extends the implicit warning in the first. Here, the encompassing landscape is lent threatening bodies. At this stage of the film narrative, Ethan and his nephew, Martin, are taking refuge in a cave as they hold off a Comanche attack, led by Scarface, who, with his band of warriors, had murdered Ethan’s brother, wife, and eldest daughter and carried off the younger one, Debbie. Rescuing Debbie and enacting revenge for the destruction of a family, which at a symbolic level stands for white domestic settlement as a whole, had become the object of Ethan and Martin’s long search, which constitutes most of the film narrative. Apart from the complications attending the motivations for the search—Ethan, a (not unredeemable) racist, had sworn that he would kill Debbie because her long captivity had rendered her unfit to rejoin white society, while Martin was bent on rescuing her—I want to focus on the rearticulation of domestic coherence versus external threat that this scene effects.

While the adventures associated with the five-year search are proceeding, a domestic drama is unfolding. Early in the film Ethan expresses contempt for Martin’s part-Indian heritage (at their first meeting he says, “Fellow could mistake you for a half-breed,” even though Martin is, by his account, only one-eighth Cherokee). However, by the time they are sequestered in the cave, Ethan has come, ambivalently, to accept his family bond with Martin, even though he continues to insist that Martin is not his kin. Given Ethan’s change in attitude, the scene in the cave becomes an instance of family solidarity. The implication seems to be that Native America can be part of Euro America if it is significantly assimilated and domesticated. Ethan effectively supports that domestication by ultimately bequeathing Martin his wealth. He has apparently discovered that part of himself that craves a family bond, a part that has been continuously in contention with his violent, ethnic policing. And on his side, Martin fulfills all of the requirements of a family-oriented, assimilated Indian. He becomes affianced to the very white daughter of Swedish Americans, after he has rejected an Indian spouse he had inadvertently acquired while trading goods with Comanches.

By becoming part of a white family, Martin is involved in a double movement. He is participating in one of Euro America’s primary dimensions of self-fashioning, its presumption that a Christian marriage is the most significant social unit (that such “legal monogamy benefitted the social order”13), and he is distancing himself from the Native American practices of which the nuclear family was often not a primary psychological, economic, or social unit (and was often viewed by settlers as a form of “promiscuity”14).

Visual analytics

How then can we read this Afghan photo (Figure 1.1) in the context of this specific part of its aesthetic patrimony? The attack on Afghanistan’s incumbent Taliban regime, however distant its territory from the United States, was sold to the American public as a legitimate reaction to the continuing threat to domestic America that was initiated by Al Qaeda’s attack on American soil, the first time in modern American history in which a domestic vulnerability has been experienced as a result of an attack by adversaries in league with forces outside the continent. Certainly the spatial and biopolitical aspects of the historical situations to which Ford’s film and the photo refer are vastly different.15 The Ford images reference an expanding frontier, as settlers and their armed protectors move in and push Native American nations westward after the Civil War. In this period, the (Euro) American military effectively had to defend a form of domestic life that existed on the same terrain as the battlefield. By contrast the cu...