This is a test

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Psychology of Consumer Behavior

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

After years of study in the area of consumer behavior, Mullen and Johnson bring together a broad survey of small answers to a big question: "Why do consumers do what they do?" This book provides an expansive, accessible presentation of current psychological theory and research as it illuminates fundamental issues regarding the psychology of consumer behavior. The authors hypothesize that an improved understanding of consumer behavior could be employed to more successfully influence consumers' use of products, goods, and services. At the same time, an improved understanding of consumer behavior might be used to serve as an advocate for consumers in their interactions in the marketplace.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Psychology of Consumer Behavior by Brian Mullen,Craig Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Comportement du consommateur. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Recall the last time you purchased a beverage in a grocery store. You located the beverage aisle, examined the various available brands, selected the chosen beverage brand, and paid for it on your way out: This seems to be an unremarkable and everyday sort of event. However, upon closer examination, there is a host of questions that are raised by this everyday behavior. How did you first become aware of the chosen beverage brand: through commercial advertisements on television, through your friends, or at the point of decision in the beverage aisle? How did you develop a positive evaluation of this brand: was it the price? Has this brand been recommended in the media by one of your favorite celebrities? Does this brand have something unique, making it stand out from the others? What made you want this brand in particular?

These are the type of questions asked within the field of consumer psychology, and this volume attempts to answer these questions in terms of current psychological theory and research. Consumer psychology can be defined as the scientific study of the behavior of consumers. A consumer is an individual who uses the products, goods, or services of some organization.

As Howell (1976) pointed out, each organization provides some product that is used by some consumers, even though we may not always recognize the products or the consumers as such. For example, it seems fairly obvious that the college students who drink a cola produced by a specific beverage company are the consumers of that beverage product. However, in a sense, we can think of public high school students as the consumers of a state’s educational product; voters can be thought of as consumers of a political candidate’s leadership and administration product; and, the members of a religious group might be viewed as consumers of a church’s spiritual product. Thus, the study of the behavior of consumers involves examination of a wide range of everyday human behavior.

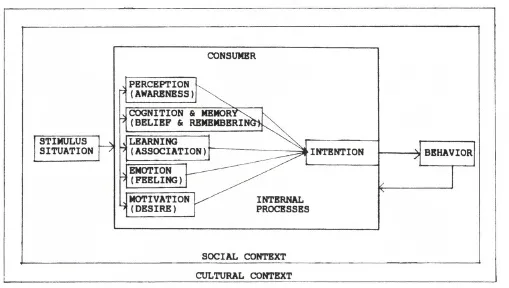

This textbook is structured around a general model of consumer behavior, presented in Fig. 1.1. This model helps the student of consumer behavior consider and deal with the variables and relationships that can affect consumer behavior. Generally, a model is a simple representation of something that is in fact more complicated. The model in Fig. 1.1 leaves out some of the complexity of consumer behavior. Nonetheless, this model contains the most fundamental and the most important elements found in other common models of consumer behavior. In a sense, Fig. 1.1 is a simplified schematic illustration of the theory and research that we call consumer psychology. In this chapter we begin our study of consumer behavior by establishing some preliminary definitions of the variables and processes presented in Fig. 1.1. Before moving on to more detailed examinations of these variables and processes in subsequent chapters, we briefly examine some other representative models of consumer behavior, and we consider some basic issues regarding measurement.

FIG. 1.1. A general model of consumer behavior

A GENERAL MODEL OF CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

Beginning at the left side of the model, notice that a box labelled “stimulus situation” is shown to influence the consumer. The stimulus situation is the complex of conditions that collectively act as a stimulus to elicit responses from the consumer. This suggests that consumer behavior is not typically thought of as being elicited by a single stimulus. Rather, consumer behavior is considered to be the consequence of patterns or constellations of stimuli. For example, when the consumer purchases a can of “Loca-cola” brand beverage, that consumer behavior was not merely the result of the cost of the product. Instead, we would have to consider the cost of the product, the characteristics of the advertisement of the product, the packaging of the product, the individual’s past experiences with the product, the placement of the product on the shelf, and so on.

At first glance, this might appear frustrating to the budding consumer psychologist; the stimulus situation that impacts upon the consumer seems to be unmanageably complex. However, it is important to recognize that the world in which consumers behave is, in reality, extremely complex, filled with continual commercials, pretty packaging, and confusing choices. The little box in Fig. 1.1 labelled “stimulus situation” is very full and busy.

Next, the model specifies a number of internal processes. These internal processes are a related series of changes that occur within the individual. Internal processes can be viewed as consequents that are caused by something else, or as antecedents that cause something else. When viewed as consequents, internal processes are thought of as the result of the stimulus situation, the individual’s own behavior, the social context, the cultural context, other internal processes, and the interactions between these sets of variables. Research that views a given internal process as a consequent treats it as a dependent variable that is influenced by some independent variable(s). When viewed as antecedents, internal processes can be considered the cause of intentions, behavior, or some other internal processes. Research that views a given internal process as an antecedent treats it as an independent variable that influences some dependent variable(s). One special case of the use of internal processes as independent variables is the concept of psychographics. This refers to the use of individual differences in the internal processes to predict consumer behavior. As discussed in chapter 8, individual consumers who are especially likely to engage in a particular internal process may be more receptive to certain types of messages.

Each of the internal processes are discussed in detail in the chapters that follow. The internal processes are considered from both the perspective of consequents that are caused by something else (i.e., dependent variables) and the perspective of antecedents that cause something else (i.e., independent variables).

Perception is typically defined as the psychological processing of information received by the senses. The result of the internal process of perception is awareness of the product, or awareness of attributes of the product. Cognition refers to the processes of knowing or thought. The result of cognition is a collection of beliefs about or evaluations of the product. Memory refers to the retention of information regarding past events or ideas. The result of this process is the acquisition, retention, and remembering of product information. Learning describes a relatively permanent change in responses as a result of practice or experience. The result of this internal process is the formation of associations between stimuli or between stimuli and responses. Emotion is a state of arousal involving conscious experience and visceral changes. The result of this internal process is feelings about the product. Motivation is a state of tension within the individual that arouses, directs, and maintains behavior toward a goal. The result of this internal process is desire or need for the product.

Note that these internal processes were defined as a related series of changes. Discussing each process separately requires the establishment of somewhat arbitrary distinctions between interdependent events. For example, after the college student first sees a commercial for Loca-cola, he or she might express an interest in the product, and a desire to buy it. Perception seems to have occurred, because the consumer is aware of the product; cognition has taken place, insofar as the consumer has evaluated Loca-cola as being worthy of consideration; motivation may have been engaged, if the student really wants to try the product; and so on. This is to emphasize that, although we can conceptualize these internal processes as separate entities, we must address their interrelationships in order to obtain a full appreciation for their effects on subsequent events (specifically, their effects on other internal processes, intentions, and behavior). Another important thing to recognize about this model is the lack of any predetermined sequencing of the internal processes. That is, the model does not assume that some internal process(es) must occur before other internal processes can occur. Thus, any internal process might come before, and influence, any other internal process.

Intention refers to a plan to perform some specific behavior. Behavior is typically defined as an act or a response. Within the context of consumer behavior, intention refers to the plan to purchase or use the product, and behavior refers to the actual purchase or use of the product. Bear in mind that this applies whether the product is a brand of toothpaste, a course in school, or a political candidate. Both intention and behavior are characterized in Fig. 1.1 as resulting from the direct and interactive effects of the internal processes. Note that behavior may influence the internal processes of the consumer. This type of feedback can have very important implications, and is considered in detail later in the book.

Social context refers to the totality of social stimulation that influences the individual. This can include friends, family, or sales personnel. The cultural context refers to the totality of cultural stimulation that influences the individual and his or her social context. This can include the individual’s culture (e.g., late 20th-century America), subculture (e.g., rural southeastern United States university students), social class (e.g., middle class), and so on. Note that the individual (with his or her internal processes, intentions, and behavior) exists within, and is influenced by, a social context. Further, the individual’s social context exists within, and is influenced by, a cultural context.

OTHER MODELS OF CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

Kover (1967) reviewed the use of models in consumer and marketing research. He noted that: “All models have one thing in common: they describe some basic behaviors, needs or situations and make the assumption that ‘this is really what man is like’. Then, the particular study builds on this model and usually ignores behavior not included in the model” (p. 129). The intrinsic value of the model presented in Fig. 1.1 is that studies built upon or interpreted within this model will be able to ignore very little, if any, behavior. This is because the model is structured to incorporate the range of variables that have been examined previously in research on consumer behavior.

However, the reader should realize that this model is not some new theoretical breakthrough, “cut out of whole cloth.” In actuality, this model is an extension and integration of many previous models of consumer behavior. These models of consumer behavior can be categorized into three types: undifferentiated, unilineal, and cybernetic. These three categories roughly correspond to the three time periods identified by Engel, Blackwell, and Kollat (1978) as pre-1960, 1960 to 1967, and 1967 to present.

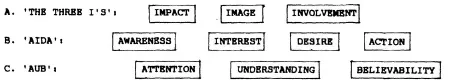

Undifferentiated Models

The undifferentiated models of consumer behavior (pre-1960) amounted to lists of variables suspected to influence consumer behavior. However, these lists of variables seldom had any integrative framework (or, any substantiating empirical evidence) to justify their serious consideration by researchers. Leavitt (1961) described a number of these early models of consumer behavior, derived from the “folk wisdom” of advertising and marketing. Some of these undifferentiated models of consumer behavior, conveyed in Fig. 1.2, are The Three I’s (Impact, Image, Involvement), AIDA (Awareness, Interest, Desire, Action), and AUB (Attention, Understanding, Believability).

FIG. 1.2. Examples of undifferentiated models of consumer behavior (pre- 1960) (Leavitt. 1961)

For example, consider an application of the AUB model to the consumer considering Loca-cola beverage. The AUB model suggests that three things must occur if the consumer is to purchase Loca-cola: The consumer must become aware of Loca-cola (attention); the consumer must understand that Loca-cola is described as a cola beverage that quenches thirst for 50¢ a can (comprehension); and, the consumer must believe that Loca-cola is a 50¢, thirst-quenching cola beverage (believability). If these three things can occur, according to the undifferentiated AUB model, the consumer should purchase Loca-cola. These undifferentiated models of consumer behavior may be useful if they suggest variables that are important to understanding consumer behavior. However, simply listing these variables, without any consideration for how the processes occur or how they interact, does not take us very far toward explaining why people will buy or use a particular product.

Unilineal Models

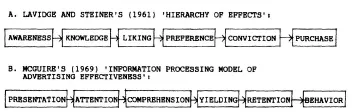

The next general trend in models of consumer behavior led to the unilineal models (1960 to 1967). These models went a step beyond the simpler undifferentiated models by arranging the list of variables in some preestablished sequence. For example, Lavidge and Steiner (1961) proposed, and Palda (1966) developed, a “hierarchy of effects” model. Similarly, McGuire (1969) proposed an “information processing model of advertising effectiveness.” These models assume a single, one-way (“unilineal”) flow of influence among the variables included in the model. These two unilineal models are illustrated in Fig. 1.3.

FIG. 1.3. Examples of unilineal models of consumer behavior (1960 to 1967)

For example, consider the application of Lavidge and Steiner’s Hierarchy of Effects model to the consumer considering Loca-cola. The Hierarchy of Effects model suggests that the following events must occur, in this sequence, if the consumer is to purchase Loca-cola: the consumer must become aware of Loca-cola (Awareness); then, the consumer must know that Loca-cola is a 50$, thirst-quenching cola beverage (Knowledge); next, the consumer must come to evaluate positively these attributes of ‘cola’, ‘thirst-quenching’, and ‘50$ a can’ (Liking); then, the consumer must come to prefer Loca-cola over all other competing brands (Preference); finally, if the consum...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Perception

- 3 Cognition and Memory

- 4 Cognition and Persuasion

- 5 Learning

- 6 Emotion

- 7 Motivation

- 8 Intention and Behavior

- 9 Behavioral Feedback and Product Life Cycle

- 10 The Social Context

- 11 The Cultural Context

- 12 Sales Interactions

- 13 Applications to Nonprofit Settings

- Afterword

- Glossary

- References

- Credits

- Author Index

- Subject Index