- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

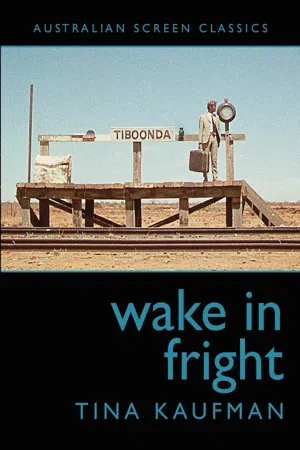

Wake in Fright

About this book

Based on Kenneth Cook's classic novel, this film about bored schoolteacher John Grant getting caught in an outback nightmare of booze, racism, misogyny and bloodlust was made in 1971 and lost until 2004.In this insightful monograph, Tina Kaufman discusses what lies behind Wake in Fright: the genesis of the film, how it was made, how it was allowed to get lost, and the long path of its rediscovery; how it was restored and received on its re-release. Tina Kaufman recounts how this film that is, in essence, all about survival, has itself survived.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Film History & Criticism1

HOW THE FILM CAME ABOUT

The late 1960s and early 1970s were the years of what has come to be called the ‘rebirth’ of the Australian film industry, although at the time nobody could ever have imagined how much that industry would grow over the next forty years and what films would come to be made. It’s fascinating that in 1971 both Wake in Fright and Walkabout screened at the Cannes Film Festival: two films made by outsiders—a Canadian and a Brit—that have come to be seen as enormously important in that rebirthing process. Both films are unlike anything that had previously been made in Australia, but of the two, Wake in Fright is perhaps the stronger, more savage and harder-hitting film. The more I discover about it, the more intrigued I am by how such a film got made, at that time and in such an unlikely fashion.

In his book on Nicolas (Nic) Roeg’s film Walkabout, Louis Nowra talks about the barren cultural landscape out of which the two films emerged. But even if it appeared barren, there must have been something there to provide the fertility for such an energetic, striving plant to germinate and eventually to thrive. Was that barrenness an illusion? Were there were little patches of vegetation and, underneath, many young shoots getting ready to sprout? Was there dormant and emerging filmmaking life in what would appear to future commentators as a wasteland?

Australia had been making films (it could only occasionally have been called an industry), since almost the beginning of cinema in the 1890s, but it had always been a very stop-start affair. In the heyday of production in the 1920s and 1930s, between ten and fifteen features were made a year, but in the years leading up to 1970 production had slowed to something less than a trickle—more an occasional splutter. Of course, there were the overseas productions. In fact, 1959 saw a veritable flurry of activity, with Stanley Kramer making On the Beach in Melbourne, Harry Watt directing The Siege of Pinchgut in Sydney, and Leslie Norman making Summer of the Seventeenth Doll also in Sydney. And in 1960 Fred Zinneman made The Sundowners with Deborah Kerr and Robert Mitchum. But not one of these directors was Australian; indeed, as critic and former Sydney Film Festival Director David Stratton says in his Afterword to the new edition of Ken Cook’s original novel Wake in Fright:

the high-profile ‘Australian’ films made during this period weren’t Australian productions at all. Most of them, including The Overlanders, Eureka Stockade, Bush Christmas, The Shiralee, Smiley, The Siege of Pinchg ut and the 1957 version of Robbery under Arms, were British films, often shot in studios in the UK with Australia used only for the location work; others, including Kangaroo, On the Beach and The Sundowners, were mainstream Hollywood productions made on location here.

And as Stratton also comments in his book, The Last New Wave: ‘Australian stories were being filtered through foreign eyes, and a strange variety of foreign actors were [sic] pretending to be Australians.’

But if very few Australian features were made, by the mid-1960s there was an active production sector making newsreels, television programs, and television commercials, while government-funded films were being produced at the Commonwealth Film Unit. Newer, lighter cameras helped the filmmakers who were making surfing, travel and adventure documentaries to go up the coast and into the bush and the outback in search of stories. There were six small studios with sound stages in Sydney, another in Melbourne, and there were about a dozen laboratories to do the processing and post-production. In Australian Cinema: the First Eighty Years, film historians Graham Shirley and Brian Adams refer to ‘more than fifty film production companies employing from five to over a hundred people each’ and comment that ‘among these various film production bodies, along with the television studios, underground filmmakers, filmmakers returning from abroad, and individual film critics, the desire for a reborn film industry grew.’

In fact, as legendary filmmaker Ken G. Hall wrote in 1967 in the short-lived theatre and film journal Masque:

there is an Australian film industry at this moment and it is keeping more people in regular employment than ever before. There are available to prospective producers ten times the facilities—studio space, modern equipment—than was available to, say, Charles Chauvel and myself in the 30s and 40s. The days of one camera and, at best, two microphones, together with some equipment made out of Meccano parts and literally tied up with wire, are no more. Much more footage is being shot than in that production heyday and there are more laboratories, including many excellent colour laboratories, than were ever dreamed of then. The trouble is that these people, this studio space and facilities, are not being used to make what most interested people would want them to be used for—feature film production.

Of course, this supposes that the production of feature films is the ultimate goal of any film industry, an issue raised by Susan Dermody and Elizabeth Jacka in The Screening of Australia (Vol 1). ‘Why is feature film production assumed to be the real point of an industry?’they ask, and continue:

The assumption goes back to the phase of film history, from the silent period to the peak audiences of 1946, when movies were the dominant popular art, when people ‘went’, on average, two to three times a week, when the industry was the third or fourth biggest revenue-earner in the United States, and there was no television. That’s part of the answer. Another part is that the marketing of films (to paying audiences, rather than to client groups, as is the case with educational films or broadcasting interests) is organised around the event of the feature, which must be large, emphatic and powerful enough to warrant travel, ticket-price and several hours of voluntary attendance in the dark.

While it is the feature film that attracts that paying audience, its production is also what many filmmakers see as their ultimate goal, and even in these bleak years some determined filmmakers did manage to make features. One was Tim Burstall, who made Two Thousand Weeks in 1969, a semi-autobiographical tale about the frustration and isolation of an artist in the Australian wasteland. Actor and writer Graeme Blundell, who was in the film, writes about the experience in his very entertaining memoir of those early years, The Naked Truth: A Life in Parts, describing it as ‘a subjective view of a writer’s crisis when he calculates he only has 2000 weeks in which to express himself.’ It was, as David Stratton (who programmed it in that year’s Sydney Film Festival) says in The Last New Wave, ‘a remarkably ambitious film’.

Tim Burstall had made a short children’s film, The Prize, which won a prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1960. He’d then made some documentaries and a children’s TV series, had been working in the US film industry for two years on a Harkness Fellowship, and thought he was ready for his first feature. Released in Melbourne in March 1969 with high (probably too high) expectations, it was reviewed badly and taken off after eleven days, while the Sydney Film Festival screening some months later was a disaster. ‘Burstall was devastated’, reported Graeme Blundell, ‘and developed a deep hatred for what he called “the intelligentsia”. They were “highbrows and ABC types” and they seemed affronted by the simple decency of the film.’ In 1971 Burstall made Stork and he had to pay for the first screening in Melbourne. It did so well that it got picked up by mainstream distributors Roadshow, becoming not only the new Australian cinema’s first box office success, but reinvigorating Burstall’s career, and scooping the pool at the 1973 AFI Awards, the year he made the highly successful Alvin Purple.7 In that film Blundell let everything hang out, shocking some of the more straight-laced critics but nevertheless delighting the cinema-going public and delivering a very large profit. But Burstall never forgot or forgave the treatment given to Two Thousand Weeks.

Behind the scenes, many of those working in film and television had been lobbying the government for years for some form of government support for production; broadcaster Phillip Adams, then both a successful advertising man and prospective filmmaker, and his friend, historian and Labor Party stalwart Barry Jones (who had been unofficially advising then Liberal Prime Minister John Gorton on cultural issues), proposed to Gorton the setting up of a national film school. In 1969 a screening for federal parliamentarians of Anthony (Tony) Buckley’s documentary, Forgotten Cinema, an account of the rise and fall of the Australian feature film pioneers, was given some credit for pursuading Gorton to finally give some assistance to the industry. (Tony, we’ll discover, will play an important role in the story of Wake in Fright.)

In 1969 the commonwealth government announced a three-part program of assistance: an investment corporation to support feature films and television programs, a national film school, and an experimental film fund to assist in the making of low-budget films and encourage emerging filmmakers. While the film school didn’t come into being until 1973, the Australian Film Development Corporation was set up in 1970, as was the Experimental Film and TV Fund, initially administered by the Australian Film Institute.

For many of those who have since written about the period prior to government support, in the numerous takes on how the industry got going again, it may have seemed a very insular, bleak and unrewarding time. For those who were there, however, it was different: their memories reveal a screen culture buzzing with activity and ideas, infused by commercial enterprise, by television and commercials, and energised by popular, classic and foreign films. Nor was it a one-way street: just as the Australian industry was open to ideas from overseas, Australian ideas, energies and talent also flowed abroad.

Take Producer Richard Brennan, for example. As he wrote in early 2009 just after his retirement as a project officer from the federal government funding body Screen Australia, he has been in love with cinema since he was ten: ‘I have read about films, watched them, and studied them. And since I was seventeen I have worked on them.’8 That all started when he met Bruce Beresford at Sydney University in 1960, ‘both dreaming of being filmmakers’, and they made a short film called The Devil to Pay. Richard then made several other short films and, upon graduating, went on to work as, first, a production assistant at the ABC, and then at the Commonwealth Film Unit (later Film Australia). In 1970 he produced and directed a documentary in support of the May moratorium which launched the anti-Vietnam war movement in Australia, Or Forever Hold Your Peace, which was the first film financed by the newly created Experimental Film and TV Fund.9 He then produced Peter Weir’s short drama Homesdale, which won the rarely-given Grand Prix at the Australian Film Institute Awards.

So, for Richard and others like him, it was a time of terrific optimism. He recalls vividly how cinema opened up the rest of the world for him, telling me:

We’d just seen two locally-made features in release, The Naked Bunyip and Nickel Queen, and at Film Australia we were working on two more, Brian Hannant’s Flashpoint and Cecil Holmes’ Gentle Strangers. We actually saw a future in filmmaking. And we were inspired by the films we were seeing; that year, at the Sydney Film Festival, I’d seen Truffaut’s Bed and Board, Peter Watkins’ Punishment Park, Pasolini’s Teorema, Bunuel’s Tristana, Eric Rohmer’s Claire’s Knee, and Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist.10

Richard’s imm...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright Page

- Author’s Biography

- Australian Screen Classics

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 - How the Film Came About

- 2 - How the Film Got Made

- 3 - How the Film Got Lost—and Found

- 4 - How the Film was Received

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Credits

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Wake in Fright by Tina Kaufman,Tina Kaufman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.